We spent two years researching this documentary. Over and over, we heard

the following refrain: "To understand this Pope, you must go back to his

Polish roots." Ultimately, everything we learned proved the deep truth of

these words. All of the major themes of John Paul II's papacy can be traced

to the shaping events of his life--a life whose roots are sunk in Polish

soil. His Christian vision, his vocation, his very emotions draw their depth

and intensity from the country he left to become Holy Father of the Catholic

Church in Rome.

We spent two years researching this documentary. Over and over, we heard

the following refrain: "To understand this Pope, you must go back to his

Polish roots." Ultimately, everything we learned proved the deep truth of

these words. All of the major themes of John Paul II's papacy can be traced

to the shaping events of his life--a life whose roots are sunk in Polish

soil. His Christian vision, his vocation, his very emotions draw their depth

and intensity from the country he left to become Holy Father of the Catholic

Church in Rome.

As the Vicar of Jesus Christ and successor of St. Peter, he has

revolutionized the office of the modern pope. He has taken his mission out of

the Vatican and around the globe, pushing back the boundaries of the old

Christian Europe--proselytizing, reforming, opening new churches wherever

he's gone in Latin America, the United States, the East and Africa. He wooed

and won the media with his personal gifts and variety. He has been the skiing

pope, the poet pope, the best-selling CD pope, the designer robes pope, the

intellectual pope.

But he has never descended into trivial celebrity. He is the pope who

brought down Communism; the pope who worked ceaselessly towards Christian

reconciliation with the Jews; the pope who raised his voice against the

contemporary evil in our "culture of death." He has never consulted

pollsters, but marched to a stern, unyielding drummer. So John Paul II has

also been the infuriating pope, the retrograde pope, the silencing pope, the

pope who has ignored the revolutionary changes in the status of women. His

uncompromising limitations--as well as his extraordinary accomplishments--

all reflect the impress of a vanished world: the Poland where Karol Wojtyla

came of age.

In the 16th century, Poland was the largest country in Europe. Slowly,

painfully, inexorably, they lost control of their superior position. For the

last two centuries, again and again, Poland has been brutally partitioned and

devoured by its neighbors. Germans, Austrians and Russians divided and

redivided the low, flat, defenseless country, drenching its borders in blood

and torturing the national psyche.

The reasons for losing their powerful place in Europe are less important

than the result. Poles remain completely preoccupied with the story of why

they fell and what has happened to them since. This retrospective legacy is shared

across all political and class divisions. Communists and aristocrats look back

with the same passion as intellectuals, peasants and artists.

The last Communist prime minister of Poland, Mieczyslaw Rakowski,

thoughtfully tugged on a Cuban cigar as he meditated on his country's history

with us. He felt he and the Pope shared a common view which he described this

way: "You have to remember that Poland during the medieval years was a power to

be reckoned with. The area of Poland was immense. It reached from the Baltic to

the Black Sea. In the 18th century, Poland ceased to exist on the European map.

The next five generations of Poles lived in slavery through partitioning. The

nation developed this inferiority complex towards other nations. History became

an obsession for the Poles, and whether you joined the Communist Party, as I

did, or the Church like John Paul II, you were reacting to the national

past."

Poland's pain lies behind every tree, every mound. The proud country

remembers every wound. Adam Zamoyski is an historian and a member of the

ancient Polish nobility. He has a confidence bred of centuries, an aristocratic

pride that feels the wound in all its freshness. "As a Pole you were born into

a bankrupt business, you weren't like other people. Every Pole has to confront-

why have we made such a mess? Three hundred years ago we were a great power and

a normal country. Then we'd become a pathetic country whose history no one

knew. Every Pole has a question mark somewhere. For the Pope, for all of us

growing up after the war, anybody going through the war, even people born in

Poland after the war were born into its arguments. We are a people stung by

history."

Not just stung by history, shaped by it. As General Jaruzelski, formerly

head of the Polish Communist Party, confided to us, "The Pope and I belong to

the same generation. We have been intellectually and emotionally shaped in the

pre-war period. We have absorbed a strong and vivid sense of Poland's memories,

especially Poland's partition and bondage. We inhaled this early history like

fresh air, like oxygen, and we lived by it. Our heroes were those who fought

against it, the heroic martyrological tradition. In my very first conversation

during martial law, he stressed that he always remembered the history of

Poland through so many tragedies, through partitions. He reaches down into

history. It is intimate with him."

The Polish nation has often only existed in the Polish mind. Having no

geography, the Poles feel history must take its place. They give the oaks of

their forests the names of lost kings. They bury and rebury their beloved

leaders.

Queen Jadwega died in 1399. Her most recent funeral was held in solemn pomp in

1973. Repetition can bring ecstatic release, but rarely closure.

As the English journalist, Neal Ascherson (who spent years covering

Poland) said to us, "It has seemed, for generation after generation, that

Polish history has a sort of cyclical form. It moves in cycles, which horribly repeat

themselves... insurrection, repression, intervals of freedom, occupation by

foreign powers, and deep moral confusion."

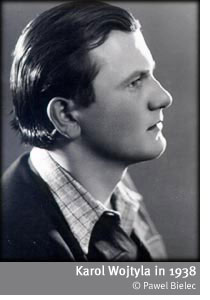

Karol Jozef Wojtyla--whose rise to the papacy signaled new hope for his

nation--was born on a day of great modern reckoning for the Poles: May 18,

1920, a day called the Polish Miracle. On that day, Marshal Jozef Pilsudski

struck a deciding blow in the war against the Soviet Union and seized Kiev. It

was Poland's first major military victory in over two centuries. It set in motion

events which briefly restored Poland's independence. Mindful of the nation's turning

point, Karol's father gave his new son Pilsudski's middle name. Some people

said he also called Karol "Josef" after Mary's self-sacrificing husband. The

confluence of history and religion were significant, as was the moment of

Karol's birth. He belonged to a generation who breathed oppression and defeat

in the air around them. But unlike their parents, they also knew what freedom

tasted like.

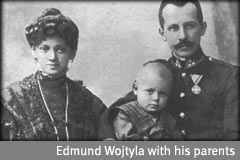

Karol's father and mother were from the Galician--or Austro-Hungarian

--section of Poland. His father's family were peasant stock, raised to

prosperity in Wojtyla's grandfather's generation. Karol's father was born on

July 18, 1879. He earned his livelihood as a tailor until he was drafted into

the Austrian army in 1900. The military became his lifetime career. Though he

never rose very far, "the Lieutenant" (as he was always called) was awarded the

Austrian Iron Cross of Merit for bravery during World War I. Photographs show

the seriousness, discipline and moral character for which Karol Senior was also

praised in his Army file. In 1906, he married Emilia Kaczorowska, the daughter

of a Krakow upholsterer. She bore him three children and became her family's

tragic muse.

Emilia was a sensitive young woman of delicate health. Her first child, a

boy named Edmund, was born the first year of her marriage--in 1906. In one of

the few family photographs of Karol Senior with Emilia and Edmund, she is

feminine and soft. Her dark eyes are meditative, subtle, slightly wary. She

was already intimate with suffering and death. As she was growing up, she

watched four of her brothers and sisters grow sick, languish and die. She lost

her mother during adolescence. Fortunately, Edmund was healthy, able, even

brilliant. Soon enough he was doing so well at school that he planned to become

a doctor. But Emilia's next child, a daughter, Olga, died in infancy around

1914. Thereafter her own health began to fail.

Emilia was a sensitive young woman of delicate health. Her first child, a

boy named Edmund, was born the first year of her marriage--in 1906. In one of

the few family photographs of Karol Senior with Emilia and Edmund, she is

feminine and soft. Her dark eyes are meditative, subtle, slightly wary. She

was already intimate with suffering and death. As she was growing up, she

watched four of her brothers and sisters grow sick, languish and die. She lost

her mother during adolescence. Fortunately, Edmund was healthy, able, even

brilliant. Soon enough he was doing so well at school that he planned to become

a doctor. But Emilia's next child, a daughter, Olga, died in infancy around

1914. Thereafter her own health began to fail.

Karol Wojtyla was born in Wadowice, in an apartment whose windows

looked out on the Church of our Lady where he would worship and serve as an

altar boy. Emilia adored him. She told the neighbors that he would be a great

man, a priest. She taught him to cross himself. She read Scripture with him.

But she was often in bed, suffering from inflammation of both heart and kidney.

She was increasingly nervous, melancholy, silent. She died on April 13, 1929

when Karol was eight. The pope's adoration of his young mother is well-known. He has

said she was "the soul of home." When she died, his father took him to

Kalwaria, a Marian shrine close to Wadowice. Karol's lifelong devotion to the

Virgin began on that trip after he lost his mother.

But there's also evidence to suggest that the boy felt deprived by his

mother's depressions. According to Carl Bernstein and Marco Politi in His

Holiness, after he became a priest, Wojtyla confided that his "mother was a

sick woman. She was hard-working, but she didn't have much time to devote to

me." When the boy turned to Mary, he may have been turning away from

disappointment as well as loss.

From the time of Emilia's death, Karol and the Lieutenant lived alone.

They were extremely close. At some point, they even started sleeping in the

same room. The Lieutenant was a force for rectitude and piety, one of several key

influences in Wojtyla's religious life. As pope, John Paul II remembered that,

"Day after day I was able to observe the austere way in which he lived. By

profession he was a soldier and, after my mother's death, his life became one

of constant prayer. Sometimes I would wake up during the night and find my

father on his knees, just as I would always see him kneeling in the parish

church. We never spoke about a vocation to the priesthood, but his example was

in a way my first seminary, a kind of domestic seminary."

Eugeniusz Mroz, one of the pope's Wadowice classmates, remembers that

"after the death of his wife, Karol's father devoted himself solely to his

son's upbringing...His father was sewing, washing, and cooking, being Karol's

mother, father, friend and colleague." The boy returned his father's devotion.

After his morning at school, Wojtyla shared the midday meal with his father. In

the afternoons, he played sports, but always went home punctually in early

evening for homework, dinner and a late walk with his sole surviving parent.

Mroz told us a story (one we never heard or read anywhere else) which

gives a rare glimpse into the intensity of the boy's attachment to his father.

While the three were hiking in the mountains, the Lieutenant walked out ahead

of the boys. Suddenly a fog came up, completely enshrouding Karol Senior. His

son immediately began to run along the path, calling out for his father. There

was no answer. He had disappeared! Karol went down on his knees and began

praying in a loud, clear voice, begging God to bring his father back safely.

Mroz knelt and prayed with Karol. When the fog lifted, they still could not

find Karol Senior and feared he might have lost his way and fallen to his death. They

rushed home where they were delightfully surprised to find Wojtyla's father

waiting for them with a cup of hot tea.

Years later, Father Figlewicz recalled seeing "the shadow of early

orphanage" in his altar boy. But the priest also described Wojtyla as

"lively, very talented, very quick and very good. He had an optimistic nature,"

and he threw himself into life with all of his incredible stamina. Along with

school games like soccer, Karol first learned to ski as a boy. He discovered

the mountains literally step by step, as he and his friends followed another

local priest, Father Edward Zacher, up the nearby slopes on their boards in the

days before ski lifts. In winter, there was skating on the Skawa, the river

that snakes through Wadowice; in summer, the boys swam there. Though their life

was simple, Wojtyla and his father had friends at church and company at home.

One of Wojtyla's closest friends, Jerzy Kluger, often dropped by and remembers

Karol Senior's passion for Polish history--his love of regaling the boys with

tales of lost battles, the heroism of St. Stanislaw and the rich history

embedded in Wawel Castle.

Father and son kept in close touch with Edmund and traveled to Krakow in

1930 to see him graduate from the School of Medicine at the Jagellonian

University. After the ceremony, Karol Senior took his boys to Czestochowa--the

heart of Polish Christianity--where Karol prayed to the Black Madonna, Queen

of Poland, for the first time. The boy was deeply moved and returned on a

school trip in the summer of 1932. That winter, the second great tragedy of

his childhood struck. Edmund--the adored older brother who shared his passion

for theatre and soccer--died of scarlet fever. As pope, John Paul II told an

audience that the impact of his brother's death was "perhaps even deeper than

my mother's." His classmates remember it that way too, that Karol cried at

Edmund's funeral, but not at his mother's. Szczepan Mogelniecki said, "The

brother's death was more his tragedy." And it bound Karol ever more deeply to

the sense that his fate was one with Poland's.

Like the nation, Wojtyla must suffer. He felt it when he prayed to Mary,

suffering Mother of Christ, in her little chapel in the Church of our Lady.

He drank in the suffering Poland in his literature and history classes. He

loved the 19th century poets Slowacki and Mickiewicz in whom the beauty and

pain of Poland was so alive. They often dealt with patriotic themes--national

uprisings, the thirst for freedom and Polish messianism. As Neal Ascherson

said in his interview, "Messianism has a very particular meaning in

Poland. It says Poland is the incarnation, it's the collective incarnation of

Jesus Christ. It is a nation which has to be crucified, in order to bring about the salvation of all

nations." Karol Wojtyla was schooled in this tradition, and he responded to it

deeply.

The young Karol memorized Slowacki's "The Slavic Pope," a prophetic

poem about a pope from the East who "will not flee the sword, /Like that

Italian./Like God, He will bravely face the sword..." In a world that had never

had a Polish pope, Karol was raised with a vision of one. From early on, he

was fascinated by the martyred St. Stanislaw, a bishop murdered by a tyrant king in

1079. As Cardinal of Krakow, Wojtyla often invoked St. Stanislaw in his

homilies and sermons. The Communists did not appreciate the reference. They

knew he stood for the power of Polish resurrection: after his murder the

enraged populace chased the king out of Krakow. As if to underline how Poles

rose from the dead, Cardinal Wojtyla had St. Stanislaw's skull dug up and

examined by forensic experts. They confirmed that he'd been executed. "In this

fashion," Tad Szulc writes in his biography, Pope John Paul II, modern

science vindicated a patriotic-religious legend." After all, Karol Wojtyla

"regarded himself as the martyred saint's successor as Bishop of Krakow--and he

owed him historical truth."

Karol first turned to theatre as the outlet for his gifts. He lacked the

self-aggrandizing qualities often associated with actors. He was a sober,

studious boy. His classmates point out how often he stands to the side in

photos of school excursions or class pictures. It was very characteristic that "Karol

stood aside...Almost every picture we have with Karol, in almost every picture,

he's somewhere aside, somewhere remote, a bit aside from all of us." He always

preferred to be an observer.

Nonetheless his patriotic passions were perfectly suited to a particular

kind of Polish theatre. In the early 1930's, he met Mieczyslaw Kotlarcyzk who

would teach him about "the Living Word," a style of performing which emphasized

language, monologues and simplicity of sets. The Living Word had its roots in

life under partition--when people sang Polish songs and recited Polish poetry

after dinner in country manor houses. It was a way of preserving their culture.

Kotlarcyzk had turned this subversive, informal entertainment into a theory of

drama.

Kotlarcyzk ran the Amateur University Theatre in Wadowice. Wojtyla began

acting in plays at school and branched out into Kotlarcyzk's productions.

The pope's public persona goes back to the declamatory style of these plays which

also emphasized, as John Paul II so often does still, symbolic gestures and

metaphor. His relationship to Kotlarcyzk launched Wojtyla as an actor and a

playwright. Their intense discussions about Polish language and culture became

the basis of an important, revealing correspondence once Karol graduated from

high school and moved to Krakow with his father in 1938. The letters that went

back and forth between Wojtyla and his mentor meant, first of all, that the

young university student knew just what was happening in Wadowice once the

Nazis invaded. Karol was kept informed of who among his friends and neighbors

had been sent to Auschwitz, who among the Jews had been herded into the

ghetto--and who among both groups had been summarily executed. Kotlarcyzk ran the Amateur University Theatre in Wadowice. Wojtyla began

acting in plays at school and branched out into Kotlarcyzk's productions.

The pope's public persona goes back to the declamatory style of these plays which

also emphasized, as John Paul II so often does still, symbolic gestures and

metaphor. His relationship to Kotlarcyzk launched Wojtyla as an actor and a

playwright. Their intense discussions about Polish language and culture became

the basis of an important, revealing correspondence once Karol graduated from

high school and moved to Krakow with his father in 1938. The letters that went

back and forth between Wojtyla and his mentor meant, first of all, that the

young university student knew just what was happening in Wadowice once the

Nazis invaded. Karol was kept informed of who among his friends and neighbors

had been sent to Auschwitz, who among the Jews had been herded into the

ghetto--and who among both groups had been summarily executed.

Karol painted pictures of wartime Krakow for Kotlarcyzk who hoped to

move there. "Now life is waiting in line for bread, scavenging for sugar,

and dreaming of coal and books." Karol also expressed despair over the collapse

of Poland and mourned the loss of "ideas that should have surrounded in dignity

the nation of Mickiewicz, Slowacki, Norwid and Wyspianski." Wojtyla saw the

University shut under the Nazis. He saw his professors rounded up and shot

or deported. He saw Jews hunted like animals.

The Nazis also waged systematic Kulturkampf by closing libraries and

shutting cultural institutions to the Poles. Only Germans could attend plays

and concerts or go to museums. A Pole could be shot for going to the theatre

and even for speaking Polish in the wrong place. When Kotlarczyk finally came to

Krakow in the summer of 1941, Wojtyla and his friends helped him start the

underground Rhapsodic Theatre. By focusing on Polish words and texts, they were

risking their lives for their country. They were also providing manna for

people starved for the sound of their own language. In a letter to Kotlarcyzk,

Wojtyla showed the missionary passion behind his cultural resistance. He wrote

his teacher that he wanted to build "a theatre that will be a church where the

national spirit will burn."

Ultimately, the two institutions would be reversed for Karol Wojtyla. The

Church would be the theatre for his Polish preoccupations. But first his

personal suffering would deepen unbearably and his country would have to be

crucified by another occupying power. Karol's father died February 18, 1941.

Though he would soon regain his outward calm, intimates in Krakow saw how

deeply this loss cut. They were worried about Wojtyla's state of mind. He was

distraught. After he found his father, Wojtyla stayed up all night praying by

the bedside with Juliusz Kydrynski, his closest friend from the theatre. He

started going to the grave every day and was so upset Father Malinski, a

fellow seminarian, "feared that something terrible might happen." As pope, John

Paul II told the writer Andre Frossard, "At twenty I had already lost all the

people I loved, and even those I might have loved, like my older sister who,

they said, died, six years before I was born."

Karol's loneliness was complete. Once more suffering fatefully bound him

to his beloved country's anguished destiny. The man who would become the

first Polish pope was first made in his landscape's likeness. His terrible losses

mounted, each a mortal blow to Wojtyla's identity, each leaving a mournful

deposit, each associated with a consoling Polish myth: Mary's enduring

compassion, the promise of national redemption, the surviving power of the

Polish language. By the time Wojtyla came of age, he bore his country's rich

themes inside him.

In his interview for our documentary, Professor Eamon Duffy of

Cambridge University, author of Saints and Sinners, described the powerful ways

suffering connected Poland to John Paul's papacy. "Suffering is crucial for

understanding John Paul, at a personal level, and at a racial, ethnic,

historical and theological level. His personal life is one of enormous personal deprivation:

the loss of his mother when he was very young; the loss of his brother who was

perhaps the person he was closest to in the world; then when he was a very

young man, and before he'd really shaped his own life choices, the loss of his

father, whose piety had been crucial in shaping his own religion...But the

Polish people for 200 years have been a victim-people, partitioned between

Germany and Russia, religiously oppressed, enslaved, abandoned by the world at

the beginning of the Second World War. And that experience of desolation for

him is part and parcel of the religious desolation of the East, a church which

is the Church of Silence, which was cut off from the West...He feels he has

given the churches of the East a special vision, a special access to the Gospel

of the Crucified...Personal suffering for him chimed in perfectly and became an

image of this greater vocation to the suffering of the churches of the

East."

We often encountered evasiveness surrounding the Pope's childhood

experience with the Jews in Wadowice. Certain facts were put forward as proof

that John Paul II had only had model relations with Jews: he and his father

rented their apartment from a Jewish landlord. Karol Wojtyla went to school with Jews.

Most importantly, as a boy, his closest friend was Jerzy Kluger, a Jewish boy

from a wealthy local family. The Pope's lifelong friendship with Jerzy Kluger

is always asserted as indisputable evidence that John Paul II never had to

overcome any limitations in his relation to the Jews. Understandably, Poles

would want to minimize the complexity, even the darkness of their relationships to Jews.

But many--not all, but many--Jews would also make an exception of Wadowice when

they spoke to us. And the world at large has accepted the version of the Pope's

idyllic hometown where Poles and Jews got along just fine. There seems to be

reluctance on everyone's part to suggest the possibility of the Pope having

been contaminated by the faintest breath anti-Semitism.

In truth, the Wadowice of his childhood was a model of Polish

anti-Semitism as well as offering him examples of cooperation. Later, as a

student in Krakow, during the Nazi Occupation, Karol Wojtyla would have been

witness to the murder of Jews in the street. He would have known about the

outright treachery of those who turned Jews in for food. He knew about the

silence of the Church during the Holocaust and after--the silence that

persisted even in 1968 when renewed hostilities forced 38,000 Jews to flee

Poland.

As we came to our project, Darcy O'Brien published The Hidden Pope.

Though it features the story of John Paul II's friendship with Jerzy Kluger,

it also contains a remarkable amount of new research on anti-Semitism in their

childhood Wadowice, in Catholic Christianity and in the Vatican. But Darcy

O'Brien died suddenly in the spring of 1998, just as he was to start his

publicity tour. We could not interview him for the film. If Jerzy Kluger had

been more willing, his interview might have helped evoke the rich detail and

complexity of O'Brien's portrait of the Catholic-Jewish world in 1920's

Wadowice. But Mr. Kluger had told his stories one too many times. He was

impatient, even unwilling, to set familiar scenes with new words. The balance

had shifted for him. It had become his story, perhaps naturally enough, but

from our point view, he couldn't serve as a conduit for O'Brien's original

research.

From his first years, Karol Wojtyla was intimate with the dark side of

Poland's anti-Semitism. As Pope, he has worked hard to recognize and

eradicate such prejudice. In the documentary, our question is not what Wojtyla did, but

why it took him so long to act and whether he had gone far enough. Here we want

to explore new biographical materials we could not include in the film and

speculate on the psychological rather than the moral springs of the Pope's

behavior.

In 1920, there were 8,000 Catholics and 2,000 Jews in Wadowice. The town

was built of narrow streets around the central square of administrative

buildings. Catholics and Jews lived in close proximity. They were the other and

the same: both chosen people with a strict religious practice at the center of

their lives. The Wadowice Synagogue was near Karol's high school, and he

watched with fascination as the Jews walked by during his classes. Years later,

as Pope, he wrote,"I have in front of my eyes the numerous worshippers who during

their Holidays passed on their way to pray." At the same time, Stanislaw Jura,

one of Wojtyla's classmates, told us, "80-90% of the Jewish population was

poor...Our connections with Jews was so rare. It wasn't very amicable. There

was a bit of anti-Semitism...A lot of the Jews had funny curls, big robes, so

there were jokes."

"The Klugers were an exception," Jura said. "Acculturated Jews like the

Klugers were just like Poles." Actually, in one respect the Klugers were also

different from most of the Polish Catholics in Wadowice. The Klugers were rich.

Jerzy's grandmother owned a lot of prime real estate in the town. Dr. Kluger,

Jerzy's father, was a lawyer whose clients included some of the most

prosperous businessmen for miles around. As much as poor Catholics resented poor Jews,

they resented rich, educated Jews even more. Father Cjaikowski, a Catholic

priest who has spoken out against anti-Semitism in Poland, told us this about its

growth in this century. "Our nation was oppressed. Always under oppression,

nationalism is born. You are sick. You are under the boot, you start to

exaggerate as sick people...After World War I, we saw we had millions of Jews. These Jews are

intelligent people, well-educated and they seem to be competition."

Polish resentment of Jews was more than economics. In fact, Father

Cjaikowski said economics was used to justify an anti-Semitism which was based

in Christian attitudes. On Good Friday, Poles said a devotional prayer which

referred to Jews as "that pernicious race." They recited the "Good Friday

Reproaches," a list of accusations against the Jews. Over Easter, there was an

annual passion play at Kalwaria, where Wojtyla often retreated to pray and walk

the stations of the cross. He also attended performances of the passion play

where his grandfather and great-grandfather had volunteered as guides. People

from all over Poland flocked to the shrine to take part in the Savior's

crucifixion. The actor stumbled and bled as he pulled the cross up the to

Golgotha. Crowds were worked to a frenzy as Jesus died the victim of the Jews:

"the Christ killers!" Afterwards, as peasants streamed out of the monastery,

their passions stirred by religion and vodka, they often attacked Jews whose

distinctive Hassidic appearance made them easy to identify.

Anti-Semitism was official Church policy. In 1936, amid the rise of

nationalism, Primate Hlond expressed it with absolute clarity in the pastoral

letter which was read from pulpits across the country: "There will be a Jewish

problem as long as the Jews remain...It is a fact that the Jews are fighting

the Catholic Church, persisting in free thinking, and are the vanguard of

godlessness, Bolshevism and subversion...It is a fact that the Jews deceive,

levy interest and are pimps. It is a fact that the religious and ethical

influence of the Jewish young people on Polish people is a negative one." The

Catholic press portrayed Jews as interlopers and Hlond advocated a boycott of

their businesses. During the horrors of World War II, the Polish Catholic

Church, as Father Stanislaw Musial told us in his passionate interview, was

"indifferent to the Jews because of bad theology...We could not help the Jews

because we had no theology for helping the Jews."

The Klugers and Hupperts were unusual, not only because they dressed and

lived like members of the Catholic bourgeoisie, but also because they strove

to provide a countervailing influence to the anti-Semitism around them. They

were extremely public-spirited. The Hupperts had donated a park with tennis

courts to the city of Wadowice. Dr. Kluger supported an interfaith string

quartet which played at his house every week. The men of the family took turns

serving as presidents of the Jewish community. According to Darcy O'Brien, the

Jews in Wadowice had looked to them for generations "for their often subtle and

complex leadership that enabled the two cultures to live in mutual tolerance."

O'Brien even describes a daily ritual that illustrated the special

harmony the Klugers and Hupperts tried to cultivate in Wadowice. "The ritual of

the old priest and the woman was always the same. Canon Prochownik would appear

at the door of Mrs. Huppert's house at the corner of Zatorska Street on the

north side of the square, where she would be waiting for him, sporting a

parasol if the sun beat down...The pair inched along toward the church and

passed it by, proceeding to the right, talking...Each time Canon Prochownik

escorted Mrs. Huppert around the square, it was a sign that all was well

between Catholics and Jews."

Dr. Kluger was a practicing Jew who rejected Jewish separatism. When

Moishe Kussawiecki, one of the great cantors and opera singers, performed at

the Wadowice synagogue, Dr. Kluger invited several Catholics, among them

Lieutenant Wojtyla and Karol. As president of the Jewish community, he raised

money to support the Jewish poor, saw that all religious facilities were

maintained, and provided Kosher food for the Jewish soldiers stationed in

Wadowice. At the same time, he spoke Polish and forbade his family to speak

Yiddish. And yet, though he felt strongly about being mainstream, he encouraged

Jerzy, his son, to report to his history class on the rise of anti-Semitism in

the national press. In short, Jerzy was raised to be free-thinking and

independent.

Karol Wojtyla was not. He was raised as a Polish Catholic. He recited the

Good Friday Reproaches and could not have missed the crowds' cries of

"Christ killers" at Kalwaria. Yet Karol Wojtyla never displayed even a hint of

personal anti-Semitism. The sole Jewish survivor of the Wadowice ghetto still

living in Poland, Zygmund Ehrenhalt, attended the public school with Wojtyla

and Jerzy Kluger. He said there were anti-Semitic students, but that Karol "was

one of those whose behavior was model."

In one of the famous stories about their friendship, young Jerzy finds

out that he and Karol are going to be in the same class at school in the fall.

He can't wait to tell Wojtyla. When Jerzy realizes he's serving at Mass, he

decides to go find him at church. The service is not over when Jerzy enters. People notice

him. In such a small town, everyone knows who he is. One old woman in

particular eyes the young Jewish boy disapprovingly. As mass ends, Jerzy races

up to the altar to tell Karol his good news. Then he mentions the old woman's

disapproval.

"Maybe she was surprised to see a Jew in church."

"Why," Karol laughs. "Aren't we all God's children?"

Besides his friendship with Jerzy, Karol often played goalie for the

Jewish soccer team. He recited Mickiewicz with his Jewish neighbor, Ginka Beer.

As he said to the Warsaw Jewish community in 1991, "I belong to the generation

for which relationships with Jews was a daily occurrence." The Jewish presence

was intimately stitched into the richness of Karol's childhood world. During a

visit from an American delegation of rabbis, the Pope was asked about his early

experiences. Rabbi Ruden told us that he watched John Paul II go into a trance

as he recollected in Proustian detail the Jewish life of Wadowice. For John

Paul II, the Holocaust brought profound, personal losses--the deaths of people

he knew and cared for. It represents another way that personal suffering bound

him to Poland's history and fate.

Wojtyla moved to Krakow with his father in 1938. By the time they left

Wadowice, the Jews were being singled out for special hardship. Members of

the National Democratic Movement had smashed Jewish shops there. Dr. Kluger was

forced to add a Hebrew version to his name on his office. Dr. Sesia

Berkowtiz who grew up in Wadowice, but now lives in Israel told us "there was

always anti-Semitism, but it wasn't brutal until the Nazis came to power." When

the Germans invaded Poland in September 1939, Dr. Kluger took Jerzy with him

into the Polish army. The men were permanently separated from the three women

of the family. As Wojtyla learned from letters that reached him in Krakow,

Jerzy's grandmother, mother and sister were forced into the Wadowice ghetto. He

knew that the Kluger women were deported to Auschwitz and that when the wind

was right, people in Wadowice could smell the ash from the crematoria there.

For a while, the sister of Karol's classmate, Eugeniusz Mroz, brought food to

the Jews in the Wadowice ghetto, but finally gave it up because of the danger.

Mroz himself watched the Germans blow up the synagogue. He gave us an

extraordinary picture he took just as the building flew into pieces.

Wojtyla would have seen the Jews in Krakow forced out of their homes and

watched while they carried their possessions into the Podgorce district.

This bestiality was carried out against the background of the most beautiful city

in Poland, the city of shadows and light, in whose very stones the country's

history was stored. Wojtyla adored Krakow, and he was shaken by the ugly

contrast between its rich antiquity and the brutality of modern war. On March

13, 1943, the Krakow ghetto was liquidated. The Germans shot scores of Jews

in lovely Zgoda Square, among them, Rabbi Seltenreich, who Wojtyla knew as the

Klugers' rabbi from Wadowice.

The destruction of the Jews in Poland during Word War II is an

extraordinary subject. Those of us who have come after cannot help but

wonder what we would have done. Within Poland itself, that question still burns,

along with passionate feelings of outrage towards certain almost unimaginable

cruelties. Konstantin Gebert, the editor of Midrash, was born after the

war. His consciousness of being Jewish was not raised until he experienced the

anti-Semitic assaults during 1968. Then he began to study and think about the

Jews' fate in Poland during the Holocaust. He told us that since he'd had

children, "I thank God every day I have not been tested. Because I fear I

would have failed the test. And my anger is not against them who refused to

help. One cannot demand heroism. My anger and utter contempt is for those who

helped the murderers. One cannot blame the Poles for not helping. This is not

the point. The point is those who helped...who would sell the Jew for a sack of

potatoes. This is what has not been accounted for."

During the early part of the war, Wojtyla showed personal courage

defending Jews. Sister Zofia Zarnecka, a university colleague, told us how

protective he was toward Anka Weber. "He often escorted her down the street and

fended off the bigots who called themselves, 'All-Poland Youth.'" We also spoke

to Edith Schiere, another Jewish Wadowician who now lives in Israel. During the

war, she miraculously escaped from Auschwitz and met Karol Wojtyla as she was

staggering down the road. He carried her to the train station on his back, put

her on the train and brought her something to eat. "I felt ashamed when my

Jewish friends said, 'Don't you know that he's a priest?' I didn't." But she

also felt terrible because she never had the chance to thank him.

There is every evidence that Wojtyla helped individual Jews because he was

a good Christian and believed in doing unto others as he would have them do

unto him. But there is no sign that he was part of any organized effort to save

Jews until some time after the war. There were Polish organizations like Zagoda

that worked to save Jews. There were priests and nuns who forged identity

papers. Poland was the only country under the Nazi Occupation where you could

be shot for helping a Jew. Adam Bujak, Poland's most famous contemporary

photographer, remembered people being shot for throwing bread over the ghetto

walls. In spite of all that, there were heroic ordinary Polish Catholics who

risked their lives to hide Jews. There are even stories of anti-Semitic

Catholics who hid Jews and resentfully called them "Christ killers" as they fed

them dinner. Wojtyla's lack of involvement is notable.

Could he have felt too threatened? It cut much deeper than simple physical

fear. Death was no stranger. He had lost mother, brother, father. Possibly

what he was feeling was his insubstantiality, that no effort however large or

small would matter. At the same time, any effort tainted by violence would put him in

the same contaminated world as the aggressors. Every event affirmed and

confirmed his helplessness and the horror of violence. When the Nazis first

arrived in Krakow, they closed the University and sent his professors to the

camp at Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg where many were murdered. One died because

he'd been doused with ice cold water and left outside in freezing weather.

Friends from the Rhapsodic Theatre had been deported to Auschwitz. Wojtyla was

himself arrested in a mass round-up in 1942, but released because he had a job

at a quarry. His papers showed he was a worker in a vital industry. Tad Szulc

describes how the other men arrested with him were sent to Auschwitz. "On a

sunny day in May, twenty-five of them were executed by a firing squad against

the 'Wall of Death' at the camp."

It was one of Wojtyla's several brushes with death during the war. At the

quarry, a worker next to him was killed. Karol was moved to the Solvay

factory,where he had more time to read and pray. But he still lived in guilt

and terror. Later, looking back on this period, John Paul II wrote, "Sometimes I

would ask myself: so many young people of my age are losing their lives, why

not me?" Possibly, his own fears shamed him: his fear of his own helplessness,

his fear of contamination, and even the fear of betraying a friend. His friend,

the writer Wojciech Zukrowski, said Wojtyla told him not to describe any

underground activities. "Karol was afraid if he were arrested, he might break

down and reveal what I'd said."

As the Nazis waged their war on the world around him, his work at the

theatre was not enough. Polish language and culture could not sustain him.

They were themselves under attack. This is how Darcy O'Brien describes the

German aggression against the Poles: "Through such methods as starvation,

imprisonment, random executions, and brutal working conditions, the Germans set

about trying to break the Polish spirit and to weed out those too biologically

weak for slavery." The German Governor of Krakow, General Frank said, "The

necessity arises to recall the proverb: 'You must not kill the cow you want to

milk.' However, the Reich wants to kill the cow...and milk it."

During the war, Wojtyla turned to the Polish Church--the only institution built on an indestructible, eternal truth. Yet even here, the Nazis

were trying to choke off the breath of Catholicism. As soon as they took over

Krakow, General Frank requisitioned the Royal Castle on Wawel Hill. He closed

Wawel Cathedral, one of the oldest Catholic repositories and the very heart of

religious life in Krakow. Frank allowed a priest to say Mass every Sunday, but

only to an empty church--Krakowians were not allowed to attend. Hitler himself

wrote General Frank that Polish priests "will preach what we want them to

preach. If any priests acts differently, we shall make short work of him. The

task of the priest is to keep the Poles quiet, stupid, and dull-witted...There

should be only one master for the Poles, the German."

Wojtyla had very real reason to believe that Nazis were going to destroy

the Polish Church, along with Polish culture and the Polish nation itself. As

Neal Ascherson said to us, "The genocide of the Poles appeared to be

already beginning...It's very difficult to imagine that people can say to themselves,

'Maybe in twenty-five years time there'll be nobody alive who speaks Polish.'

It seems outrageous, unimaginable. But that's how people thought. And the Nazis

helped them to think like that, by what they said and what they did." After all

he'd lost, the terror of losing the Word was too much. The Germans could kill

priests, but not the Priesthood; they could destroy churches, but not the

Church. When Karol Wojtyla joined Archbishop Sapieha's secret seminary in 1944,

he was giving himself to the only power of goodness left in a dark world. He

accepted it on its own terms. It was the last bastion of everything he loved.

It was not in his power to change it--not yet.

The Polish Church survived the war after all. What stronger argument could

there be for the triumphal view of Catholicism? Wouldn't it be natural for

the young Wojtyla to revel in the strengths his Church had shown? Or to depend on

his sense of the invincible Catholic Church as Stalin's new regime of terror

descended on Poland? As he moved from priest to Bishop, we know from Darcy

O'Brien's reporting that he was thinking and rethinking his war experience. In

1964, he was invited to Rome to participate in Vatican II. The bishops

discussed Nostra Aetate, in which John XXIII redefined the Catholic Church's

relation to the Jews. The document plainly said that the Jewish people were not

guilty of killing Christ. And it clearly asserted that Judaism has its own

ongoing integrity --Christianity had not replaced Judaism in God's eyes.

There were many bishops at the Vatican II Council who did not want these

points included. James Carroll, a former priest and well-known author, had a

friend who was there and told him about the fierce debate which took place over

whether or not the Jews were guilty of Christ's murder. In his interview with

us, Carroll recalled his friend saying, "All of a sudden down at the end of

the table, a man began to speak, a voice that he had not heard in any debate.

In many, many debates, on many other questions, he had never heard this voice.

He knew that it was a different voice because of the heavy accent. And the man

spoke of the Church's responsibility to change its relation to the Jews...'I

lifted up my head. I thought, Who is this prophet? I looked down and it was

this young bishop from Poland. And no one even knew his name. And it was the

first intervention Wojtyla made at the Council. And it was very important.

That's the beginning of the large public impact he would have on this

question."

It's significant too that Wojtyla made his remarks outside Poland. We

never found evidence that he went on record within his own country before he

became Pope. In Poland after the war, there was a silence about the Holocaust.

Wojtyla was part of it. Everyone had suffered so much. Three million Poles died

in the war, and three million Jews. Every Polish family had lost someone.

There were simply not enough tears for the Jews. There was silence, but it

went beyond the indifference and guilt for not having done enough for the Jews.

There were also shockingly enough, reports of Poles killing the few surviving

Jews when they returned from the camps to reclaim their property. It happened

in Wadowice. It happened all over. Father Cjaikowski heard confessions from his

parishioners who admitted to hurting Jews, to holding on to their property and

on occasion, to murdering them: "it was as if the Jews were not human," he said

sadly. "It was as if the Jews were animals."

In 1968, the Communists stirred up a new and terrible anti-Semitic

campaign. The Catholic Church did not speak out. There was still no theology

for helping Jews. Some 34,000 Jews left Poland, among them Uliana Gabara,

Assistant Provost for International Education at the University of Richmond,

and her husband, Wlodek. "'68 was an absolute nightmare," she told us when we

spoke to her in New York. "The Communists were worried about a new assertion of

Polish nationalists. My mother said, 'You'll see, they'll blame it on the

Jews.' We jumped on her, deriding her pessimism. But soon it was on the radio

that the Jews were responsible. They started beating up people who looked like

Jews. Word was spread around that Minister of Higher Education had issued a

paper saying no Jew would teach in any higher institution. Wlodek was teaching

at Poly Tech. Then the Communists made it known that any Jew who wanted to

leave could apply to the Dutch Embassy to go to Israel, no where else. It was

terrifying. You never knew if they would OK you. In order to apply you had to

bring a request for permission to give up your Polish citizenship, a paper

from your employer, a paper from your housing...They considered our request for

three months. Then they give us only two weeks to get out. We had a piece of

paper saying, Holder of this document is not a Polish citizen. It was valid for

two weeks. In those two weeks we had to fold up our lives."

Cardinal Wojtyla did not speak out against the "bloodless pogrom" in

1968. Neither did Primate Wyszynski, though he did in one public sermon,

denounce the violence against the students and other nationalities, a veiled

reference to Jews. Given the tortured history of Catholics-Jews throughout

history and, in particular, during World War II, this silence is

extraordinary. Furthermore, by 1968, Hochhuth's play, "The Deputy," about the

silence of Pius XII during World War II had exploded onto the world stage. It

was showing in Krakow. The silence of the Church during World War II was a

subject being discussed, even written about, by Father Bardeicki in Tygodnik

Powszechny .

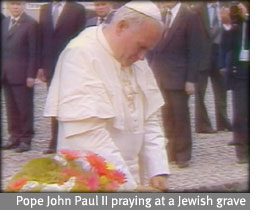

Cardinal Wojtyla did make an extremely unusual personal gesture. At a

different time, in a country with a developed media, it would become a highly

visible public statement. He visited the synagogue in the Jewish District of

Krakow. No cardinal had ever made such a visit, but Tad Szulc, a biographer of

the Pope (and our consultant for this program), claims that

"Wojtyla insisted on doing it as a gesture of friendship and because he had

fought so hard for the Vatican Council's declaration removing the blame for

Christ's death from the Jews." We talked to Tadeusz Jakubowicz, son of the

chairman of the Krakow Jewish community who permitted Cardinal Wojtyla's visit.

Tadeusz remembered the visit, but not that it was prompted by any position the

Cardinal had taken in Rome. For him, the visit was a gesture Wojtyla made in

reference to the wave of anti-Semitism in 1968. For us, it was a rehearsal for

his historic visit to the Roman synagogue in 1986.

Few Polish Catholics raised questions about Wojtyla's silence before he

became Pope. Even fewer Polish Jews spoke out about it. Those who did

insisted on anonymity. An unnamed source--a former prime minister after

Communism fell, and an admirer of the Pope, would not go on-camera with his

revealing story. He told us that he actually asked Cardinal Wojtyla why he

would not speak out in 1968. Our source felt he should have. Cardinal Wojtyla

could only answer by shaking his head and putting his face in his hands.

The Director of the Jewish Museum in Warsaw, Feliks Tych, never met

Wojtyla, but has a complex sense of Wojtyla's reticence. He is one of the

rare Poles who was willing to go on record on this subject. In his

pre-interview, Tych said, "There are contradictions. Yes, he made the leap,

but there remain contradictions. There was a silence after the war. A shock, but no post

Holocaust shock. There was silence in the Church--and yes, I know it was

dangerous, but they could have spoken...On every level, they could have done

something." Then he reflected with us on why it took Wojtyla so long to act.

Finally, for Tych, the decisive moment was when Wojtyla got out of Poland. "I

only noticed it--his difference--when he became Pope. The key to his whole

attitude became more visible when he became more independent from the Polish

Church."

Few Polish Catholics raised questions about Wojtyla's silence before he

became Pope. Even fewer Polish Jews spoke out about it. Those who did

insisted on anonymity. An unnamed source--a former prime minister after

Communism fell, and an admirer of the Pope, would not go on-camera with his

revealing story. He told us that he actually asked Cardinal Wojtyla why he

would not speak out in 1968. Our source felt he should have. Cardinal Wojtyla

could only answer by shaking his head and putting his face in his hands.

The Director of the Jewish Museum in Warsaw, Feliks Tych, never met

Wojtyla, but has a complex sense of Wojtyla's reticence. He is one of the

rare Poles who was willing to go on record on this subject. In his

pre-interview, Tych said, "There are contradictions. Yes, he made the leap,

but there remain contradictions. There was a silence after the war. A shock, but no post

Holocaust shock. There was silence in the Church--and yes, I know it was

dangerous, but they could have spoken...On every level, they could have done

something." Then he reflected with us on why it took Wojtyla so long to act.

Finally, for Tych, the decisive moment was when Wojtyla got out of Poland. "I

only noticed it--his difference--when he became Pope. The key to his whole

attitude became more visible when he became more independent from the Polish

Church."

Tych quickly added that Wojtyla had never been suspected of any kind of

anti-Semitism. Still, he was part of a Church which had anti-Semites in it.

That, for Tych, was the reason Wojtyla did not act until he got to Rome. "The

answer lies here in Poland. In leaving Poland, Wojtyla freed himself to act, to

start the re-education program regarding Jews in the Church, to forge

diplomatic ties with Israel, to write the document on the Shoah."

Along the way there would be missteps: the convent at Auschwitz and the

crosses that still remain--why did it take so long for the Pope to ask the

sisters to move the convent back? There was also the canonization of Edith Stein, a Jewish

convert who died in Auschwitz. Critics of the Pope claimed she died as a Jew,

not because she was a Catholic martyr. Neal Ascherson

sees a fascinating

trajectory in the Pope's attitude towards Jews who convert. Ascherson was at

Auschwitz when the Pope visited in 1979. "I remember a long line of nuns went

past him and he blessed each one of them...Afterwards somebody who was

standing beside him said, 'The most extraordinary thing happened. One of the

nuns stopped and said, "I want you to know that I am a Russian Jew who

converted."' The Pope was immensely moved, tears ran down his face, and he

embraced her. I think that's very significant. Because he isn't free, to put it

mildly, of Catholic triumphalism about other faiths,even within Christianity."

Ascherson went on to point out that the Pope saw the Jewish nun's conversion to

Catholicism as a form of self-transcendence. For critics, Edith Stein is

emblematic of an imperial Catholic impulse to celebrate those who have seen the

light. Ascherson and others would credit the Pope for having developed further

than that. He has left his condescension behind--as demonstrated by his very

first words in the Jewish Synagogue when he called the Jews, "My older

brothers..."

In the end, John Paul II's journey is more, not less, remarkable for its

trajectory, for the growth and change, for evident deepening as he struggled

to overcome the limitations he inherited.

home |

discussion |

interviews |

his faith |

testimonies on faith |

the church and sexuality |

the pope and communism

biography |

anecdotes |

his poems |

"abba pater" |

encyclicals |

video excerpt |

tapes & transcripts |

synopsis |

press |

teachers' guide

FRONTLINE |

pbs online |

wgbh

web site copyright WGBH educational foundation

|