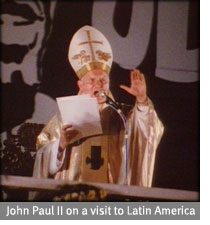

In the film, we treated SOLIDARITY and LIBERATION THEOLOGY as

distinct aspects of John Paul II's papacy. Here we want to look at them

together. It is both useful and usual to do so. Observers often argue that the

Pope saw Latin America through a Polish lens--that his difficulties with the

liberation theologians stemmed from his parochial view of the world.

There is obvious truth here. From earliest childhood, Karol Wojtyla was

immersed in the Polish Catholic Church, a Church that was intimately bound

up with the nation--which actually was a separate nation during partition --

the one place Polish was always spoken, Polish customs were always honored,

Polish history always remembered. As Roberto Suro, a correspondent for The

Washington Post, said in his interview, "In Poland, the Church was the

cradle of Polish identity. It was the incubator. It was the one place where Polish

identity survived depressions, Napoleon, the Russian, the Fascists, the

Communists...The one institution that survived and preserved a sense of Polish

identity has been the Church. And the Church has done that in part because it

has been unified."

The Polish Catholic Church has always been intensely authoritarian,

orderly, hierarchical. An able boy like Wojtyla was formed by the priests. They

literally taught him everything he knew: Father Zacher, his elementary school

teacher, also taught him to ski; Father Figlewicz, Karol's religion teacher at

high school, instructed him as altar boy at the Church of Our Lady; Father

Leonard Prochownik, for a while the priest in Wadowice, preached Catholic-Jewish

partnership. These patriarchal figures recognized his abilities--his

facility with language, his gifts as a writer and depth as a thinker. They made

sure the boy was handed up the only ladder of opportunity in Poland: the steps

advancing through the Catholic Church. His Wadowice mentors were delighted when

Archbishop Sapieha noticed their star student during a visit to their town.

The Church drew from a small pool of talent in Poland. That chance

encounter may have paid off during the war when Sapieha chose Wojtyla as one

of his secret seminarians. In 1946, the same year Sapieha ordained Wojtyla, he

sent the young priest to Rome for graduate study. It was not just Father

Karol's first chance to see the world, it was also the world's first chance

to see him. It was the beginning of his being known in Rome. Before Cardinal

Sapieha died in 1951, he turned Wojtyla's future over to Archbishop Barziak.

He arranged for the young priest to take a second doctorate and later was

instrumental in persuading Primate Wyszynski to put Wojtyla forward as bishop.

When Bishop Wojtyla accompanied Wyszynski to Rome for Vatican II, he

found Father Deskur, a friend from Sapieha's wartime seminary, ensconced as

the council's press secretary. Deskur introduced Wojtyla to many Vatican

insiders and helped lay the foundation for his coming finally to Pope Paul VI's

attention.

If Wojtyla had not impressed people on his own, these connections would have

meant little. At the same time, such a system leaves its mark. Those who have

been lifted through the ranks become hierarchical and authoritarian in their

turn. As Pope, John Paul II has paid assiduous attention to his appointments

(virtually all of his bishops share his views), and has never shrunk from using

his power against whatever is egalitarian, inchoate and disorderly.

Liberation theology was nothing if not egalitarian, inchoate and

disorderly.The social problems that liberation theology responded to were

extremely messy. The issues were different in Brazil than they were in

Argentina; they were different in Chile than they were in El Salvador and

Nicaragua. But overall, power was in the hands of the few at the expense of the

many. In 1968, the bishops of Latin America decided the Church had to commit

itself to a preferential option for the poor. In the decades which followed,

the Church in Latin America was fractured, overwhelmed and left-wing in

varying degrees, depending on the country.

Roberto Suro told us that "over the course of ten, fifteen years that

idea, that strategy, that priority evolved into many forms of action that get

lumped into the idea of liberation theology, but basically means that the

Church's primary mission had to somehow bring about change in Latin America."

Until then, in most places, the Church had sided with the status quo--with the

rich and powerful. From that time, the hierarchy was undermined because there

was conflict between bishops who favored social action and those who were

essentially apologists for the upper classes and for the military regimes.

According to Suro, John Paul II's condemnation of liberation theology was,

"'There will be no double magisterium. There will be no double hierarchy.'"

The Pope saw liberation theology, first of all, as a challenge to Church

hierarchy. He instinctively reacted against the participatory democracy

inside the base communities where priests and congregations mingled freely.

Secondly, the Pope distrusted the openness to difference and discussion within

these communities. As Suro said, "The Church he understood and loved was

unified in opposition. He grew up in a Church that always had its back against

the wall, that was trying to survive an atheistic, totalitarian regime...In

Poland, the Church was going in one direction against one foe." This single-minded focus

put blinders on John Paul II in Latin America. When the liberation

theologians said "Marx," the Polish Pope heard "Communism." When the clergy

pointed to the widespread suffering of the poor, the Pope said they were

blessed by richness of spirit. When priests invited the people up to the

altar, the Pope cried "anarchy." When priests and nuns took up arms against

massacre, John Paul II roared at them to "Pray!"

He could not see any similarities between the social revolution in Latin

America and the democratic revolution in his Poland. Nor could he admit

to any contradiction in his handling of the situations. From the time he was

elected, the Pope's trips between Poland and Latin America were often back to

back. The contrast between his activism at home and his repressiveness abroad

frequently stood out in stark contrast. In January of 1979, John Paul II went

to Mexico, attracting the largest crowds in history (estimated at five million

people) and showing he was a political force to reckon with. He used his power to

denounce liberation theology. "When they begin to use political means," he

said. "They cease to be theologians."

In June of the same year, John Paul II flew to Poland. Everywhere he went

the extraordinary crowds chanted, "We want God. We want God." In the presence

of his combustible countrymen, he all but lit the torch, "Any man who chooses

his ideology honestly and through his own conviction deserves respect...The

future of Poland will depend on how many people are mature enough to be

non-conformist."

In 1980, when the workers struck at Gdansk, there were posters of the Pope

everywhere. He supported the strike from the Vatican and sent word to

Primate Wyszynski to do the same. When the regime imposed martial law in 1981, the

Pope expressed outrage in his radio broadcasts and started sending material,

spiritual and financial support home. In 1982, Father Jerzy Popieluszko began

joining sit-ins and speaking out against the regime. Poles flocked to his

church because of his radical politics. John Paul II personally encouraged his

work by sending him a crucifix through friends. It was not long before Father

Popieluszko was considered such a challenge, the Communists had him

murdered.

Meanwhile, in South America, John Paul II raged against priestly

involvement in politics. In 1982, the Pope stopped in Argentina. As he

decried the Falkland war, his priests and nuns expressed their support for it

by waving banners, saying, "Holy Father bless our war." In 1983, he made his

famous trip to Central America where his clerics held a number of positions in

the left-wing government. John Paul II publicly scolded Ernesto Cardenal. In

private, he negotiated the ex-communication of Miguel D'Escoto, a Jesuit who'd

joined the Sandinista's government with permission from his order. In 1984, the

Brazilian Franciscan Leonardo Boff, a brilliant liberation theologian, was

summoned to the Vatican to answer for his latest book. In it, he used Marxist

language to critique the Church and analyze its mission. He was silenced,

forbidden from speaking or publishing his work. Ultimately, Boff felt compelled

to leave the priesthood.

Meanwhile, in South America, John Paul II raged against priestly

involvement in politics. In 1982, the Pope stopped in Argentina. As he

decried the Falkland war, his priests and nuns expressed their support for it

by waving banners, saying, "Holy Father bless our war." In 1983, he made his

famous trip to Central America where his clerics held a number of positions in

the left-wing government. John Paul II publicly scolded Ernesto Cardenal. In

private, he negotiated the ex-communication of Miguel D'Escoto, a Jesuit who'd

joined the Sandinista's government with permission from his order. In 1984, the

Brazilian Franciscan Leonardo Boff, a brilliant liberation theologian, was

summoned to the Vatican to answer for his latest book. In it, he used Marxist

language to critique the Church and analyze its mission. He was silenced,

forbidden from speaking or publishing his work. Ultimately, Boff felt compelled

to leave the priesthood.

On and on--there are endless examples of the Pope creating "free zones"

in Poland and shutting them down in Latin America. The people who criticize

John Paul II for never getting beyond Poland pitch their tents right here. As

professor Ron Modras, a former priest who has written about the Polish

Catholic Church, said to us, The Pope "speaks eight languages: Polish, Russian,

German, French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and English. Yet, he opens himself

to the accusation of being provincial. He thinks in Polish. He is the most

traveled world leader in history,and yet he exemplifies how narrow the vision

from the Vatican can be and has been." In fact, John Paul II has surrounded

himself with so many Poles it's said among Vaticanistes in Rome that "the Tiber

will run red with Polish blood" when the Pope passes on.

He sought advice on Latin America from all his advisors, but in the end,

the Pope was uncompromising. "As a Pole," Professor Tony Judt of New

York University's Remarque Institute said, "he does not compromise with

secular authority. The whole history of Polish Catholicism, of Polish romantic

nationalism, of Polish idealism in all its political and secular forms is a

history of non-compromise."

The criticism is real, but it ignores what the Pope's trip to Cuba

demonstrated: that he was capable of developing his views over time. When

Communism fell in Poland, John Paul II was bitterly disappointed by his

countrymen's response to freedom. Poland, Christ of Nations, was supposed to

lead the world in spiritual values--not hurtle down the slippery slope of

Western capitalism. But his Poland did just that: embraced consumerism, celebrated

licentiousness and legalized abortion. Meanwhile, as the military dictators

fell and civil wars ebbed in Latin America, the base communities which were at

the heart of liberation theology survived. They fostered the sort of social

fabric the Pope approved of: communal solidarity built around the church. In

Cuba, John Paul II went beyond messianic Catholicism and simplistic

anti-Communism --two central elements of his Polish background. He promoted a

new synthesis, calling on Fidel to grant his people more religious freedom,

and praising the people for keeping their socialist ideals. Critical of both

Marxism and capitalism, it was the vision of a man who had learned from his

experience.

Women are the thorn in John Paul II's side. Their challenge pains him,

more than pains--at this point, their demands and criticisms enrage him. Yet

the searing controversies surrounding birth control, divorce and the ordination of

women are not going to disappear. The revolution in women's rights is

on-going. John Paul II's opposition to it is fixed. His rigidity is well-known.

What's been obscured is the passionate intensity of his feelings for and about

women. Far from being Solomon sending down laws from above, John Paul II seems

more like King Lear, grief-stricken and confounded that his call to obedience

drives his daughters away.

By now it is his biographical donee: his mother's death when he was eight

was the defining experience in his relation to women. The boy was too stunned

to even respond. He was encouraged to treat his paralysis as courage and

release his emotions at Kalwaria. There, as he poured his grief into his prayers to the

Virgin Mary, he gave his broken heart into the keeping of the celestial Mother

of God. It was the beginning of his lifetime devotion to a woman he would never

touch, who was more perfect than any that walked the earth, who herself could

do no wrong.

As Professor Tony Judt pointed out to us, "One has to think of this man

as having unconsciously chosen to devote his life as a preteenager to the memory

of mother, and consciously chosen to devote his life as a teenager and

afterwards to the cult of the Virgin Mary. Those are related convictions and

related devotions, and this is a man of powerful convictions and of a powerful

capacity to live them out." Perhaps the first way the young Wojtyla lived these

beliefs was by taking a personal vow of chastity as a teenager. According to

Politi, the biographer who first wrote about his oath, it was common for

zealous young boys of that time to take such a vow. But in a phone interview

before he went on-camera, Politi also said he had every reason to believe the

Pope has kept his vow of purity. The virgin boy became a celibate priest.

At the same time, Karol Wojtyla has always had close women friends. He

was, of course, extremely handsome; he is charismatic; he is a good

listener:everything women like in men. But John Paul II has also enjoyed the company

of women, learned from them, even worked with them on projects he considers

extremely important.

He began his lifelong friendship with Halina Krolikiewicz, the renowned

Polish actress, in high school. Because they saw each other every day for

years, she is now routinely assumed by the Western press to have been the

Pope's girlfriend. Anyone who wants to interview Halina must first convince

her that the agenda is not an "expose" of their early romance. Nonetheless,

according to Politi, there was an erotic charge to the relationship. They

acted together both in Wadowice and in the Rhapsodic Theatre in Krakow. Some

observers feel that Halina helped Wojtyla polish his rough edges. She would

not comment on that. She told us only that "he analyzed everything, thought

everything through. But he also had a sparkle, an ironic sparkle in his eye."

Danuta Michalowska, who was one of the actresses in the Rhapsodic Theatre,

remembered Wojtyla's joyousness too. "How would he show his happiness?" she

asked during a long conversation at her apartment."Dynamically. When he had new

ideas about the text, he would walk on his hands with his head

down to show his happiness."

Though he seems never to have had an intimate relationship himself, Karol

Wojtyla always had an open, even searching interest in the love relationships

of others. As a young priest, he was very involved in the lives of the young

people who hiked and canoed with him. Marie Tarnowska, a psychologist, who has

known him since childhood, told us he was "a second father to her." During a

time when she was quite unhappy, Father Wojtyla urged her to start coming on

the wilderness trips. She described how he spent part of every day--whether in

a kayak or hiking--with one of the students. That way, they all each had time

to develop their own particular relationship with the young priest.

"It was very personal," Marie Tarnowska said. "He did not talk about

general problems, but problems of the person with whom he was talking -- in

connection with our relationship or families. He was always interested in

problems of marriage...He liked to see when the young people were falling in

love and getting married...He was interested in this ethically, wanting to

discuss how real love was, not to fall into illusion--whether someone really

loves a person or his imagination of the person."

Though Father Wojtyla entered into his students' romantic lives, he seems

never to have struck the wrong note. He was not voyeuristic or intrusive. In

spite of his own inexperience, he could be helpful. None of the couples who

married out of these groups has ever been divorced. Some of them claim it's

because Father Wojtyla never interfered. Even when he disagreed strenuously, as

he did with Marie Tarnowska's choice of a future husband, he was tactful.

Marie Tarnowska told us that he had a particular young man in mind for

her and said she should educate him to be her partner. "I didn't know much

about educating young people at that age," Mrs. Tarnowska laughed. "Shortly

after, I met my future husband, and there was this sparkle...When I came to

Father Wojtyla, this was my confession. I'm saying, 'Dear Uncle, excuse me, I

think I fell in love,' and his reaction was, 'Yes, I know.' So he was quite

observant. He was very alert in his heart towards what was going on, and he

knew that I was in love although I hadn't said that before to him."

Wojtyla's interest in relationships led to Love and Responsibility,

an extraordinary book for a cleric to write in Poland in the late 1950's. The

book built on what he learned from his students and his study of anatomy,

physiology and contemporary sexology. In the process of writing it, he also

developed a working relationship with Dr. Wanda Poltawska, a rather strange

Krakow psychiatrist, whose clinic counseled couples on love and sex. Her

research, she claimed, offered scientific justification for the orthodox

Catholic position on birth control. However, her research has not been

substantiated by follow-up experiments or reviewed in major medical

periodicals. She told Jonathan Kwitny that her work proved "the use of

contraception leads to neurosis." Her data bolstered Wojtyla's views on sexual

conduct and she provided him with a wide range of cases he otherwise might not

have known about.

The book recommends sex education, provides charts of the female fertility

cycle, and boldly emphasizes the importance of a woman's orgasm. As amazing

as it was for Wojtyla--a bishop by the time he published Love and Responsibility in 1960--to take up for female orgasm, the book's focus

on sex is subordinate to the concern about sexual ethics. The Pope's central

concern is the danger of turning the other person into an object, of using him

or her for your own ends. It's also a strangely poignant book. Beneath the

dense philosophic arguments and all the clinical terms, there is a lonely man

earnestly trying to come to grips with the flesh and blood reality of the sex

he is sworn not to touch.

Dr. Anna-Teresa Tymieniecka--who would become Cardinal Wojtyla's

most important, possibly the only, female collaborator--was not impressed

by what he had to say about sex in Love and Responsibility. "I thought

he obviously does not know what he is talking about. How can he write about

such things? The answer is he doesn't have experiences of that sort...He's

innocent sexually, but not otherwise." Dr. Tymieniecka, a Polish aristocrat

married to an American, is a widely-respected, published philosopher. It was

the philosophy in Love and Responsibility that impressed her, as it was

the philosophy in The Acting Person, published in 1967 which moved her

to seek the author out in person.

It was the beginning of an intense four years of collaborative endeavors.

Dr.Tymieniecka has gone on record with some of the most nuanced personal

insight we have about this Pope from a woman. As she told Carl Bernstein and

Marco Politi, "He is a man in supreme command of himself...He has developed in

himself an attitude of modesty, a very solicitous way of approaching people. He

makes a person feel there is nothing else on his mind, he is ready to do

everything for the other person." But along with his modesty, Dr. Tymieniecka

also saw his powerful, deliberate, unwavering strength. "People around him see

the sweetest, (most modest) person. They never see this iron will behind

it...The work going on in his mind...His usual attitude is suavity. His iron

will is exercised with suavity and enormous discretion. It doesn't manifest

itself directly." Nor is he truly modest, according to Dr.Tymieniecka. "He is

by no means as humble as he appears...He thinks about himself very highly, very

adequately."

The most important work they did together was to translate The Acting

Person into English. Meeting for hours at a time at his office in

Krakow, in his car when he traveled, at her house in Vermont, they talked out Cardinal

Wojtyla's ideas--and hers--and worked through the style of their expression. As

dense as The Acting Person is, the version he worked on with Dr.

Tymienieska shows a clarity and simplicity that his earlier philosophic

writings lack.

The man who was so open to Dr. Tymieniecka closed down as Pope. In 1977,

Cardinal Wojtyla acknowledged the impact she'd had on his work. He wrote an

introduction thanking her and signed over the world rights of their English

edition. In 1978, he was elected Pope and the Vatican tried first to stop

publication, and then when that failed, next to discredit Dr. Tymieniecka's

edition by attacking her in the Catholic press. The Pope assented to the

Vatican's approach. He was silent. She protested vigorously and found

significant support from other philosophers who could see her contribution.

Under public pressure, the Vatican slowly softened its position. One afternoon

on her terrace in Vermont she shared her sadness with us. She speculated about

the sources of their estrangement (which is now repaired). Did the Vatican fear

there would be gossip about their relationship? Or were they worried that a

woman had made too great an intellectual contribution? Because she has recently

reconciled with the Pope, she now refuses to discuss their estrangement at

all.

John Paul II has also assented to the traditional Church teachings on

birth control, abortion, divorce, women's ordination. They are the mainstream

Catholic views he has always subscribed to. But growing numbers of Catholic

women do not. As their challenge has grown, the Pope's positions have

stiffened. Vocations for women are plummeting. In Latin America where Catholic

women commonly practice birth control, seek abortions and get divorced,

thousands have left John Paul II's Church to join the Pentacostal Protestants.

He offers no olive branch.

In his encyclical "On the Dignity and Vocation of Women," John Paul II

applauds the revolutionary changes in women's lives and opportunities. He

approves of women working in the world. And he praises their "special

sensitivity." But he insists that they must accept their God-given role as

Mother (whether or not they have children), and they must not disturb the

integrity of their God-given gender. The importance of maintaining the

difference between the sexes is absoluteto the Pope. It is why he has said

women may no longer even discuss ordination.

As his line has hardened, his temper has flared. In 1985, he made an

extraordinary remark in an argument with Nafis Sadik, then undersecretary of

the UN Conference on Population and Development. As she recounted to us, they

were discussing the agenda for the Cairo Conference. It became a veiled

disagreement about the role of abortion in the developing world. Sadik insisted

that the matter had to be addressed. Domestic violence was on the rise; women

often became pregnant unwillingly. John Paul II burst out angrily, "Don't you

think that the irresponsible behavior of men is caused by women?"

Perhaps such a view is not surprising in a Polish patriarch of the Pope's

generation. The boy who turned to the Virgin Mary for mothering would

naturally see Eve as a temptress. But then where is the boy who befriended

girls so easily? What has happened to the young man who protected Anka Weber;

the young priest who intuitively followed the motions of Marie Tarnowska's

heart; the intellectual who was so open to the mind of Dr. Tymieniecka? Where

is the sympathy that always seemed to mark his relations with women? Why is

there no negotiation? Why is change so, so fearful here?

John Paul II has not made his feelings plain. He rarely, if ever, does on

personal matters. People have said this to us repeatedly. His closet friends

from different stages of his life, from Halina, a childhood companion; from

Professor Stefan Swiezawski, his thesis monitor; from his Wadowice classmates;

from Dr. Karol Tarnowski, a former student who talked about his personal

relationship with Father Wojtyla on the canoeing trips; from Halina

Bortnowska, another student and ultimately, a colleague: all describe the

Pope's gift for intense listening. All say he can give his total focus to

another person, but cannot or will not reveal himself. So we can only

speculate on why he is so rigidly opposed to any change in women's role.

A Vatican insider, Joaquin Navarro-Valls, described Wojtyla's mother "as

'burned' emotionally and physically by the circumstances of her life and her

time--by unbearable disappointment at the death of her daughter and by the

difficulties of an era of war and economic privation." A boy whose idealization

of the Virgin defended him against disappointment would be very different than

one who reached for the continuation of a real and richly complicated loving

mother. Along with all the chill that comes with age, all the tension that

comes with intense disagreement, perhaps the emotional intensity of the

argument with and about women forces the Pope to face a truth too bleak to

bear. He did not just lose his mother; he never had her. Perhaps that is why

he resists these changes so strenuously. If he gave up his ideal, he would

have nothing.

John Paul II's conflict with the contemporary world runs deep. He deplores

our use of science, media, law, politics, money and feels our

"systematically programmed threats" to life amount to a "culture of death." What does death

mean to him here? As professor Tony Judt so brilliantly said, "Death

is hopelessness...social death, the death of culture, the death of the family,

the death of moral commitment, the death of faith, the death of the

possibility in the belief in higher values. These are what he means by a

culture of death. Life is about absolutes. Death is about relatives."

"The Gospel of Life," the encyclical in which John Paul II expresses

this vision, is urgent and unrelenting. Some people have described the experience

of reading it as having the Pope's finger in their face, his voice raised,

demanding that attention must be paid. It is his bleakest and most personal

statement, rooted in the dark shadows of his hard life in Wadowice and Krakow

under Nazi and Soviet Occupation.

John Paul II's conflict with the contemporary world runs deep. He deplores

our use of science, media, law, politics, money and feels our

"systematically programmed threats" to life amount to a "culture of death." What does death

mean to him here? As professor Tony Judt so brilliantly said, "Death

is hopelessness...social death, the death of culture, the death of the family,

the death of moral commitment, the death of faith, the death of the

possibility in the belief in higher values. These are what he means by a

culture of death. Life is about absolutes. Death is about relatives."

"The Gospel of Life," the encyclical in which John Paul II expresses

this vision, is urgent and unrelenting. Some people have described the experience

of reading it as having the Pope's finger in their face, his voice raised,

demanding that attention must be paid. It is his bleakest and most personal

statement, rooted in the dark shadows of his hard life in Wadowice and Krakow

under Nazi and Soviet Occupation.

The Pope's losses have never been catalogued so succinctly--or so

starkly--as they were by Professor Tony Judt in this extraordinary summary:

Karol Wojtyla "was born in 1920, shortly after World War I into an impoverished

Poland, into a family where, one by one, his closest relatives died around

him...He was left before his 21st birthday with no family. At about the time of

his father's death, shortly before, World War II broke out, and he lived in

Poland under the worst dictatorship ever known...And then this man lives in

post-war Poland for twenty years under Communist occupation when Poland was a

grim, depressed, dishonest, duplicitous, impoverished gray place."

These losses are familiar and often repeated. It needs to be repeated.

What's less well known is the number of times the Pope himself has nearly lost

his life. Karol was ten when he had his first close brush with death. A

playmate aimed his father's rifle at Karol as a joke. The gun was loaded. He pulled

the trigger and a bullet flew by Karol's face, missing him by centimeters. In

1939, the Lieutenant and Karol tried to flee Krakow during the Nazi advance. As

the father and son joined a column of refugees outside the city, low-flying

German planes sprayed the group with machine guns. After Karol began work at

the Solvay plant, a worker next to him was killed in an accident. At 21, Karol

was arrested in a Nazi round-up and narrowly escaped being sent to Auschwitz.

At 23, a speeding German army truck hit him from behind and drove on

without stopping. If a woman had not happened on the comatose man and called

for help, Karol might have died. He woke up in the hospital covered with

bandages, suffering from a severe concussion. On August 6, 1944, a week after

the Warsaw Uprising, the Nazis swept Krakow, arresting every adult male as a

precaution against their staging another organized uprising. In his basement

apartment, Karol lay praying in the shape of the cross. The Germans stormed

into his apartment building; he could hear their boots taking the stairs two at

a time as they went through the top floors. He heard the boots descend.

Miraculously, the Germans did not take the stairs to the basement. The next

morning, a messenger came from Sapieha to bring Wojtyla back to the secret

seminary.

Even as Pope, John Paul II's life was threatened by an assassin's near

fatal bullet. But the attacks which left their mark on his character and mind

were those he experienced as a young man in Krakow during World War II. Those

threats permanently impressed on him the presence of real evil in the world.

Having come so close to being killed by vicious invaders, there was no way

Wojtyla could shut his eyes to the terror and death around him. It was worse

than being a soldier in battle--a soldier might at least have a fighting

chance amid the blood, smoke and mayhem. Wojtyla lived something possibly even

more nightmarish than the battlefield. In Krakow during World War II and after,

he lived the Apocalypse. He saw his city overrun again and then again by the

Four Horsemen: Conquest, Slaughter, Famine and Death.

In Poland, we often heard from members of his generation that the war was

their defining experience. The Pope's classmate Szczepan Mogielnicki said,

"Childhood! What was childhood: mother, father, home, school. The war made us

who we are." Professor Jerzy Kloczowski, a historian who lost his arm in the

war, told us he was convinced that "the traumatic experience...of the two

totalitarianisms" and the "extermination of inconvenient people" was the

deciding factor for his (and the Pope's) generation. It was the horror, but it

was also seeing how it broke people, how good people betrayed each other and

forever brooded through their lives: did they do enough? "We were tested in

ways that people in the West have never experienced," Professor Kloczowski

said. And he is right. In our country, the McCarthy Era--with its own

histories of small and large betrayals--did not begin to give us a taste of

this moral contamination.

The Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs, Krystof Sliwinski, knew Cardinal

Wojtyla through Tygodnik Powszechny. Sliwinski is twenty years younger

than John Paul II, but his memories of the war are burnt into his psyche. He feels

its significance is immeasurable. "We were witness to two major evils of this

century. That is even more important than what is called Polishness...We'll

never be innocent bystanders again...That makes us different from the rest of

the world. Not as Poles, but as generations born between 1910 and 1930. We

share the war."

Gradually, Karol Wojtyla has accepted suffering as part of his vocation.

Suffering is a crucible, but as we all know suffering can as easily open as

close you off to what the Pope feels is a world of pain--a community of

sufferers. He calls suffering his "necessary gift," and it binds him to every

other suffering person, makes him reach out to the sick, the wounded, the poor

all over the world. In ways both noble and unnerving, he asks for suffering. He

offers himself as a sacrifice.Those who have watched him with the sick and the

dying and the deformed have been quite shaken by his transformation. He draws

energy from other people's pain. He seems spiritually recharged, less frail,

walking with a firmer step, lit from within.As our camera lingered over the

faces of people he left behind, they too were refreshed.

Karol Wojtyla was shaped by stark colors of black and white. He knew

Auschwitz. He has lived to see science improve every method of killing: the

barbarity of genocide and war, the so-called "civilized" methods of

abortion, execution, euthanasia. Karol Wojtyla knew Soviet censorship, a time when you

could not print the simple truth. He has seen people give up samisdat for

violent videos. Karol Wojtyla was poor. Except for Jerzy Kluger, most of his

friends were poor. He has lived to see the rich get unbelievably rich and the

poor pushed out of our sight. Karol Wojtyla has taken life very, very

seriously. But he's left the Manichean world of darkness and light, a world of

chiaroscuro, and journeyed into the pastel valley of Disneyland. He has watched

the world prefer a carnival mood. The Pope has experienced the twin evils of

the Nazis and totalitarianism. He is a witness to the deaths of 20 million. He

knows there are spiritual dangers in this new world that are worse than the

ones he left behind.

Because of who he is and what he has gone through, he cannot stand by. He

cannot ever be an innocent bystander again. He rages against the advancing

culture of death with righteous, Old Testament thunder. When we first read "The

Gospel of Life" we're struck with emotion--shame, regret, the desire to do

better--feelings we wish weren't dormant, but are. His language bristles with

proper passion for the things that matter: the value of life, the meaning of

suffering, personal dignity. Yes, he's right to question our "Promethean

attitude," the fact that we treat "everything as negotiable." We had not meant

to fall so far away from our true ideals.

In the end, though, he makes many of us uneasy. We admire his seriousness,

but we cannot accept his sense of absolute truth. He is entitled to oppose

abortion; others are entitled to accept it. Relativism brings dissatisfaction,

dissent, profound unease, but we can't just turn away from individual rights. John Paul

II feels we can. As Professor Judt observed, "He regards the Enlightenment,

what we think of as the moment of the coming of modern thought,

the belief in the rights of man, the beliefs in equality, the belief

in democracy as the product of another mistake, the mistake that human kind

made in abandoning faith and God two, three hundred years ago in the West. And

his task is not to put that mistake to rights. He simply behaves as though it

hadn't happened...That is his relation to modernity."

John Paul II's life story is extraordinary. But his suffering also marks

him as a man of a particular time and place and Catholicism. The autobiography

which shaped his vision of the culture of death also limits it.

For all the qustions this Pope has raised, there is one that burns for John

Paul II--the question of faith. For him faith is the first, the ultimate

reality. He has circled the globe without cease, swimming in people, touching

them, provoking them--putting his faith in their faces. Why?

home |

discussion |

interviews |

his faith |

testimonies on faith |

the church and sexuality |

the pope and communism

biography |

anecdotes |

his poems |

"abba pater" |

encyclicals |

video excerpt |

tapes & transcripts |

synopsis |

press |

teachers' guide

FRONTLINE |

pbs online |

wgbh

web site copyright WGBH educational foundation

|