But in the end the Pope also knows, as Monsignor Albacete said, "that he cannot

give his faith to anyone. All he can do is offer clear testimony and bear

witness to what he believes is the deepest part of the self." The Pope has

spent his life writing, talking and bearing witness to faith. It is for him, as

well as for us, private, mysterious, ineffable.

But in the end the Pope also knows, as Monsignor Albacete said, "that he cannot

give his faith to anyone. All he can do is offer clear testimony and bear

witness to what he believes is the deepest part of the self." The Pope has

spent his life writing, talking and bearing witness to faith. It is for him, as

well as for us, private, mysterious, ineffable.

However, if we cannot hold the Pope's faith in the palm of our hand, if we

cannot bend or shake it, how can we talk about it? What is his testimony?

Where does his faith come from? How has it sustained him? How has he

sustained it? If John Paul II--the chief articulator of the Catholic

faith--has not given us real answers, how can we find them for ourselves?

On the surface, John Paul II's faith seems contradictory:

- He is a man of fierce Catholic emotion and sensibility: passionately devoted

to the Virgin Mary and the saints, attentive to--and accepting of --the

miraculous and the inexplicable. At the same time, he is a professional modern

philosopher, defending the capacity of the human intelligence and profoundly

respectful of the scientific quest for truth.

- He has lectured at Harvard University, but has also traveled devotedly to the

tomb of a southern Italian miracle worker who was able to be in two places at

the same time.

- He believes in absolute truth and absolute moral values, and yet he has

devoted his entire efforts as a moral philosopher to the modern notions of

experience and subjectivity.

- He passionately defends the rights of the individual

and just as passionately defends ancient dogmas that seem to restrict that freedom.

It is not enough to say that from the Pope's perspective these are not

contradictions. Nor is it enough to recognize that the modern papacy places

conflicting demands on the Pope who as preacher and prophet may extol things

which as an administrator of a complex bureaucracy, he must curtail, manage,

even condemn. What we can do is acknowledge these "contradictions" but also see

them as more apparent than real. "Layers" is perhaps a more searching and

useful term than "contradictions;" it leads us into the heart of the mystery

rather than into a debate about consistency.

Karol Wojtyla's truth--his faith--is profoundly layered, starting at the

deepest level with his having to find meaning in a stunning catalogue of

personal losses: his mother died, his only brother died, his father died, his

nation was occupied and his culture was threatened with extinction, his

university was closed and many of his professors were executed, his Jewish

friends and families were uprooted and killed in the Holocaust-- all by the

time he was 25. The young Wojtyla found strength in what he believed was the

will of an unfathomable God.

The total mystery of God led in turn to an experience of what he understood as

the "mystery" of man, namely, the link with the Absolute which he identified

with the deepest level of personal experience. This link with the Transcendent

became for him the defining experience of personhood, present and perceived

each time the human person expressed his identity through action. His passion

for poetry and drama was born from this conviction, and they became the

principal weapon in his opposition to the humanisms that denied this spiritual

root of human activity. His philosophy sought insights of the existentialists

and phenomenologists with their emphasis on human interiority. Although

eventually he was to find their thought inadequate, he saw their mission as

opening up traditional Catholic thought to the reality of experience and

subjectivity. His rejection of much of modern thought as leading to "the

culture of death" was born from what he claimed is the absence of the truly

spiritual in modern ways of thinking about human life.

The dramatic nature of Polish Catholicism, and its application of the Christian

doctrine of the Incarnation, Death and Resurrection to the efforts to defend

Polish identity from extinction, led John Paul II to the centrality of the

person of Jesus Christ. The horrific potential of mankind that Karol Wojtyla

experienced close up made the question 'Who is Man?" all the more urgent. The

Christian answer--that it is only the mystery of Christ that reveals the

mystery of the human being and the mystery of creation--is the key to Wojtyla's

theology. It led him to value the works of Henri de Lubac and other theologians

of the back-to-the-source school who insist that the most basic characteristic

of Christian thought is the acceptance of "paradox."

It could be said that the efforts to bring together in perfect harmony the

human and the divine, the eternal and the timely, the unlimited and the

limited, the historical and the unchanging, the physical and the spiritual is

the source of the apparent 'contradictions' in John Paul's faith. The powerful

and paradoxical image of Christian triumph--the crucified God --sustains him.

It allows him to find gain in loss, hope in suffering, purpose amidst chaos.

There is a fiery, mystical core to the young Wojtyla's faith. It is the

deepest, darkest layer of the soil which has nourished him throughout his life.

All his early heroes are passionate visionaries: the strange, otherworldly Jan

Tyranowski; the Spanish mystic, St. John of the Cross; the stigmatic faith

healer, Padre Pio. Their emotional, poetic view of the world has sustained him

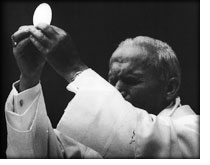

throughout his life. This is a man for whom the great religious truths are

viscerally experienced. Christ is alive and walks the earth; the Virgin is a

real woman; the Devil is a person not an abstraction. Good and evil are

powerful autonomous forces battling each other--the powers of darkness and

light. As Pope, he has attended exorcisms, and even officiated at one.

Over the years, his readings and discussions, his dissertations and sermons,

and, ultimately, his many encyclicals and many pronouncements, have added

important layers of thought and feeling to the young Wojtyla's passionate

mysticism. His study and reflection only deepened his faith and gave him

confidence, as he wrote: "I lived in a world of faith in an intuitive and

emotional fashion...(and discovered) that it is a world that can be justified

by the most profound as well as the most simple reasons."

As with so many of the great themes of this man's life, the origins of his

piety are revealed in his biography--a life whose roots are sunk deeply into

the richly layered Polish soil. We must go back to Poland to find the clues and

intimations suggesting the origins, the texture and the singular intensity of

John Paul II's faith.

Karol Wojtyla was baptized on June 20th in a little church on the square. His

family lived in a modest apartment directly across from the church. The bells

marking the religious devotions of the day filled the apartment with their

noisy pealing. As one of the Pope's biographers, Jonathan Kwitny, observed:

"The apartment was so close to the church that a priest with an average nose

would have smelled the family dinner--the church virtually cast a physical

shadow over Wojtyla's home and undoubtedly cast a spiritual shadow as well."

Karol Wojtyla's parents were intensely religious, unusually so, in a time where

religious devotion was normal in Polish families. Upon entering Wojtyla's small

apartment, there was a bowl of holy water in the hall blessed by a priest. His

mother had created a small altar in the parlor where the family would gather

for morning and evening prayer.

The seeming contradictions in John Paul II's faith start here in the

discrepancy between his school and the church--between his training in reason

and in his exposure to mysticism. Professor Norman Davies, the Polish

historian, told us that he'd been thinking about writing a biography of the

Pope, among other reasons because of his fascination with "the conflict in

Wojtyla's moral horizons...between the Catholicism that was very devotional,

ritualistic, very counter-reformation, theatrical, filled with dressing up,

pilgrimages...with displays of great religious piety...and its possible

conflict with the atmosphere of his school which was a classical Latin

curriculum with an emphasis on rational argument and logic .... the dichotomy,

the two sides of his being go back to his starting the day as an altar boy in

the parish church and then going up the hill on the same day and being the star

pupil in the Greek and Latin class."

After his mother died his father immediately took Lolek (as his classmates

called him) and his brother to pray at the Kalwaria Zebrzydowska sanctuary. In

addition to everything this experience must have meant to him about Mary, it

was also a primary source of his deep mysticism. He would have seen (and

joined) along with tens of thousands of fellow Poles, the crowds of believers

on their hands and knees, praying and chanting as they reenacted Christ's

Passion, his betrayal, his crucifixion and his resurrection. These processions

lasted for days and were intensely dramatic theatrical spectacles.

The Pope has mentioned Kalwaria in his writings, and in private conversations

with friends, as a powerful shaping influence on his spiritual life. In our

interview with Adam Bujak, one of Poland's most celebrated photographers (and a

friend of the Pope), Bujak described to us the effect of this pilgrimage on

him as a young boy of twelve. Bujak watched the procession from a tree and

experienced this drama as "shattering--indelibly marking his faith." Years

later, he created Misteria, the legendary book of photographs about

Kalwaria's Passion Play. In stark black and white images he captures histrionic

scenes of worship--crowds lined up by the road to watch the manacled Christ stagger

towards his death; men and women spread-eagle on the ground sobbing.

For Bujak, these pilgrimages are an expression of the depth of Poland's

religiosity where every road at Easter becomes a sacramental byway for

pilgrims. Other Poles see Kalwaria as an expression of the theatricality --and

thinness--of Polish faith. One of Poland's great novelists, Andrzej Szcypiorski

cautioned us not to confuse intensity and drama with depth--"Poland's religious

fervor is external, tied to symbols, to dramas, to rituals--the Pope's

mysticism and interiority is striking but not typically Polish." John Paul

II's early involvement with these pilgrimages was deep and personal; he plumbed

their essence, not their theatricality. In a conversation with Jonathan

Kwitny, Halina Bortnowska described Wojtyla's unique spirituality in even

blunter terms: "It was very unusual for a Polish clergyman to write his

dissertation on St. John of the Cross. We are a theatrical, ritualistic people.

He is private, mystical, altogether different."

Looking back years later, John Paul II remembers the profound effect his

mother's death had on his father's spiritual life--and on his own:

"The violence of the blows that struck him opened up immense spiritual depths

in him; his grief found its outlet in prayer. The mere fact of seeing him on

his knees had a decisive effect on my early years...Even now when I awake at

night I remember seeing my father kneeling and praying. He was so hard on

himself that he had no need to be hard on his son; his example alone was

sufficient to inculcate discipline and duty...My father was the person who

explained to me the mystery of God...."

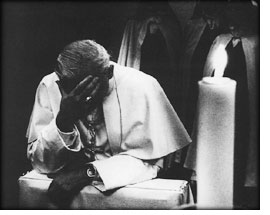

Lolek was remembered by his childhood friends as an unusually pious but not

priggish young man. Many of them recalled for us the unusually long time that

he would pray. He would stop by the church before school and stay longer on his

knees than any of his classmates, lost in thought, mouthing his prayers

silently. His preferred place of meditation was not the main sanctuary but a

tiny chapel off to the side which had a statue of Mary. His complete absorption

in prayer would grow over the years--both in duration and in intensity.

Sometimes his entire body would express this intensity of abandonment. When

Karol felt he was alone--or in great danger--he would pray face down on the

stone floor, arms outstretched in the shape of the cross. His university

friend, Wojciech Zukrowski, told us that when the Nazis made a sweep of Krakow

rounding up young men for the work camps, they searched Wojtyla's house. Karol

had hid in the basement, praying face down on the damp floor, arms

outstretched, while he heard the thud of Nazi boots overhead. His chauffeur, Josef

Mucha, told us that "one morning I forgot to knock, my hands were filled with

his breakfast, and when I entered I found him asleep on the floor, arms

straight out, his body a perfect cross, a rug thrown over the lower

half of his body. Clearly he had slept this way the entire night."

While his father played an extraordinarily important role in shaping his son's

religious life, there were others who influenced his growing vocation. Father

Kazimierz Figlewicz, who served as the vicar and religion teacher at the

Wadowice church, had a remarkable touch with young students; he was not only

able to recognize their gifts but to communicate with them with ease and

intimacy. Apparently, he reached the young detached Lolek at a very deep level

and soon after he became Wojtyla's confessor. Later on, when he was

Archbishop, Wojtyla described Father Kazimierz as "the guide to my young and

rather complicated soul."

|  |

Father Kazimierz was present at one of the most desperate moments in Wojtyla's

life--a stark coincidence of religious life and historical drama. It was a

moment which revealed Karol's highly-developed sense of calm and submission to

God's will so often remarked on by people. Karol had arrived early for Mass at

the Wawel Cathedral on September 1, 1939. The cavernous church was empty, only

Father Kazimierz was waiting for him. The Germans had entered Poland and were

about to make their first bombing runs over Krakow. The two men began serving

Mass as the bombing began. As Father Kazimierz described it to Adam Boniecki,

biographer of Karol Wojtyla, "It was the first wartime Mass before the altar

of the crucified Christ and the scream of sirens and the thud of explosions

have remained forever in my memory--nonetheless Karol in his imperturbable way

had crossed over the bridge and walked to the Cathedral because he was always

observant in his religious commitments." After he left Mass, he walked through

the agitated crowds with his friend, the actor and theater director, Juliusz

Kydrynski. Germans pilots were dropping bombs all over the city. The two

friends stood inside a courtyard watching the smoke and mayhem...Juliusz

remembers Karol's calm demeanor: "All hell was breaking loose--and Karol stood

by the wall as it trembled in its foundations not showing the slightest

fear--if Karol was praying, he was praying in his soul quietly..."

Father Kazimierz was present at one of the most desperate moments in Wojtyla's

life--a stark coincidence of religious life and historical drama. It was a

moment which revealed Karol's highly-developed sense of calm and submission to

God's will so often remarked on by people. Karol had arrived early for Mass at

the Wawel Cathedral on September 1, 1939. The cavernous church was empty, only

Father Kazimierz was waiting for him. The Germans had entered Poland and were

about to make their first bombing runs over Krakow. The two men began serving

Mass as the bombing began. As Father Kazimierz described it to Adam Boniecki,

biographer of Karol Wojtyla, "It was the first wartime Mass before the altar

of the crucified Christ and the scream of sirens and the thud of explosions

have remained forever in my memory--nonetheless Karol in his imperturbable way

had crossed over the bridge and walked to the Cathedral because he was always

observant in his religious commitments." After he left Mass, he walked through

the agitated crowds with his friend, the actor and theater director, Juliusz

Kydrynski. Germans pilots were dropping bombs all over the city. The two

friends stood inside a courtyard watching the smoke and mayhem...Juliusz

remembers Karol's calm demeanor: "All hell was breaking loose--and Karol stood

by the wall as it trembled in its foundations not showing the slightest

fear--if Karol was praying, he was praying in his soul quietly..."

There were other events, other mentors, who helped to shape his spiritual life.

His high school teacher, Father Edward Zacher, was a brilliant scientist as

well as a theologian who constantly encouraged his students to look deeply and

without fear into the mysteries of the heavens and the secrets of the

microcosmos. He was an unusual priest for his time and place; his confident

faith is unusual even today. For Zacher, there was no conflict between faith

and reason. This theme is, of course, defining of John Paul II. As Pope, he

has encouraged scientific research; he listens rapt to the latest discoveries

of scientists who gather at his summer retreat at Castle Gondolfo; he urged a

Church commission to clear the name of Galileo. His latest encyclical, "Fides

et Ratio" (Faith and Reason), is the final expression of this deep-rooted

conviction.

Arguably the most important of all his spiritual mentors was Jan Tyranowski. He

met Tyranowski on a cold Saturday afternoon in February 1940, at a weekly

discussion group in the parish church; it was a crucial moment in Wojtyla's

life. Tyranowski was a strange man--a forty year-old tailor with white-blond

hair, a high-pitched laugh and piercing eyes. Neighbors spoke to us about his

oddness and his intensity. He was a bachelor who lived with his mother in a

small apartment across the street from the Wojtylas. Tyranowski's small rooms

were filled with stacks of religious books, sewing machines and several cats.

He would stop young men on the street and try to interest them in joining his

"Living Rosary," a praying circle and theology discussion group for young

people. He recruited youngsters so aggressively that one of them, Mieczyslaw

Malinski, the future priest and seminarian friend of Wojtyla, remembers being

alarmed by his intrusive personal questions and worried that he might be a

Gestapo agent. Father Malinski told us that it took him a long while to warm up

to "this bizarre character who talked in a high-pitched affected voice."

Wojtyla, however, was immediately gripped by Tyranowski's personality and the

power of his ideas. Tyranowski and Wojjtyla spent an increasing amount of time

together discussing the Scriptures and mystical philosophers such as St.

Theresa of Avila and St. John of the Cross. Malinski tried to argue with Karol

about this strange man and even brought up rumors that he had been in a mental

institution. Father Malinski wrote about Karol's response in his own biography

of the Pope: "Tyranowski has gone through a major life-changing conversion.

Look at what is inside him, not his outward experience. Yes, he speaks in a

slightly odd, affected manner, but look beyond that. He is a man who lives

truly close to God." For Karol, Tyranowski was aflame with God--and this

closeness to the flame was an irresistible quality for the young Karol and

would remain so for the rest of his life.

Ultimately, Father Malinski grew attached to Jan Tyranowski and entered the

rigorous world of The Living Rosary: "When Karol and I committed ourselves to

this prayer group, it was all-encompassing. Every moment of the day was

organized around activity and relaxation. We were asked to keep detailed

records of our prayers and thoughts. Tyranowski took us through each stage very

calmly and methodically until we reached the central core of his teaching--what

he called the plenitude of inner life. His influence on Lolek was gigantic. I

can safely say that were it not for him, neither Wojtyla nor I would have

become priests."

Wojtyla later wrote about this defining experience: "What Tyranowski wanted to

do was work on our souls--to bring out the resources he knew existed within

us." Karol was particularly struck by the quiet, mystical core of his

teaching and he remembered vividly the day and hour when his teachings sank

into him: "Once in July when the day was slowly extinguishing itself, the

word of Jan Tyranowski became more and more lonely in the falling darkness,

penetrating us deeper and deeper, releasing in us the hidden depths of

evangelical possibilities which until then we had tremblingly

avoided...Tyranowski was truly one of those unknown saints, hidden among others

like a marvelous light at the bottom of life at a depth where night usually

reigns. He disclosed to me the riches of his inner life, of his mystical life.

In his words, in his spirituality, and in the example of a life given to God

alone, he represented a new world that I did not yet know. I saw the beauty of

a soul opened up by grace. "

One of the Pope's most insightful biographers (and our consultant), Tad Szulc, believes that the influence of

Tyranowski on the young Wojtyla flowed from their shared attraction to the

mystical quality of spiritual life: "Tyranowski gave a wholly new dimension

and understanding to Karol's instinctive mysticism and, as much as any profound

experience of his young years, it set him on a course towards the

priesthood...his mystical legacy to Karol Wojtyla was the 16th century poet and

mystic, St. John of the Cross and the desire for the contemplative life." (In

fact, after he became a priest, Wojtyla, on two separate occasions, requested

permission from his superiors to enter a Carmelite monastery; each time they

refused, believing his gifts lay elsewhere.) One of the Pope's most insightful biographers (and our consultant), Tad Szulc, believes that the influence of

Tyranowski on the young Wojtyla flowed from their shared attraction to the

mystical quality of spiritual life: "Tyranowski gave a wholly new dimension

and understanding to Karol's instinctive mysticism and, as much as any profound

experience of his young years, it set him on a course towards the

priesthood...his mystical legacy to Karol Wojtyla was the 16th century poet and

mystic, St. John of the Cross and the desire for the contemplative life." (In

fact, after he became a priest, Wojtyla, on two separate occasions, requested

permission from his superiors to enter a Carmelite monastery; each time they

refused, believing his gifts lay elsewhere.)

During our interview with Dr.Susan Muto, an expert of the life and work of

St. John of the Cross, she speculated on why Karol's first encounter with St.

John was so overwhelming:

"Of all the writers in the mystic tradition, he is the most riveting. The sheer

metaphoric power of his language is stunning, filled with images of darkness

and light, and it must have been a transforming experience for this young man

witnessing the horrors of the war...Karol was obviously drawn to this mystic

and influenced by him at the very deepest level. St. John's clarion cry is that

the proximate way to wisdom is through purgation, through profound suffering,

both physical, emotional and spiritual...."

While each of the Pope's biographers might emphasize different influences

shaping Karol's spiritual life, all of them agree that it is impossible to

overestimate the impact of St. John of the Cross. However, it is important to

place the experience of Karol encountering this powerful mystic in the context

of his life. By 1939, Karol Wojtyla had experienced the death of his mother

and brother (he would soon lose his father). Close friends were dying in the

war, or simply disappearing off the streets never to be seen again. His

country might well be destroyed. These losses opened him to ultimate

questions--and to the particular vision of St. John of the Cross.

As the Catholic writer, Michael Sean Winters, explained it to us:

"St. John allowed Karol to integrate these horrific losses in his life and to

find meaning in what he was going through. For St. John of the Cross, there is

great spiritual value and meaning in privation, in suffering, in the "Via

Negativa." Each loss hastened Wojtyla's thoughts beyond the horizon of human

cognition, beyond the traditional Catholicism of his upbringing. Perhaps it is

the absoluteness of death that helped shape the young Karol's conviction that

the world has no answers to this enigma. So far his God has taught him that he

must find life in death, gain in loss. St. John was the perfect guide. So, in

the place of his revered but departed earthly mother, his devotion to the

Virgin Mary, the heavenly mother, became more pronounced. The mystical "Via

Negativa" of St. John of the Cross opened up a world for Karol in which loss

was gain, death was life and the Church was seen as the ultimate paradox--the

sign of contradiction."

On February 18, 1941, exactly one year after he met Tyranowski, Karol suffered

possibly his greatest loss--the death of his father. Unlike his calm demeanor

and stoic submission to God's will following the deaths of his mother and

brother, the loss of his father provoked a torrent of tears and visible pain.

He lamented bitterly that he had not been present when his father died. His

friend, Maria Kydrynska, was with Karol when they returned home to discover

that Karol Wojtyla Sr. had died of a heart attack in bed. She described the

scene vividly to Tad Szulc before she died a few years ago: "Karol, weeping,

embraced me. He said through his tears, 'I was not present when my mother died,

nor when my brother died.'" The apartment was too painful to stay in alone, so

he moved in with the Kydrynskas. Years later, John Paul II told the writer

Andre Frossard: "I never felt so alone." His friend Father Malinski observed

him going to the cemetery every day to pray at his father's grave and said to

us, "Karol was so distraught that I was truly worried about him."

Some of Karol's friends have said to us that they felt that this wrenching blow

of his father's death was decisive--and that it led ultimately to his decision

to become a priest. It was almost as if the smell of death was ammonia to him.

It awakened him. It helped convert him. It sharpened his focus. It gave him his

vocation. It also freed him. As Maria Kydrynska said to Szulc, "The fact that

he was alone without his parents, it was as if it was his destiny."

From that point onwards, Karol spent a great deal of time with his mentor, Jan

Tyranowski, but it would take a year and a half for his vocation to take final

shape. Years later the Pope would reflect on the mystery of his vocation in his

memoir: "At 20 I had already lost all the people I loved. God was, in a way,

preparing me for what would happen....After my father's death I became aware of

my true path. I was working at a plant and devoting myself, as far as the

terrors of the occupation allowed, to my taste in literature and drama. My

priestly vocation took place in the midst of all that--I knew that I was called

with absolute clarity."

Father Malinski was present at this spiritual turning point and wrote about it

in his own biography: "It was 1942, bitter cold, I was waiting outside the

priest's residence at Wawel Cathedral for Karol to finish his confession with

Father Kazimierz. Their conversation went on for hours and I became restless,

even worried. When Lolek emerged he was very quiet as we walked across the

bridge. Finally he said to me, 'I have decided to become a priest and that is

what we were talking about.'" Father Kazimierz had taken him to Archbishop

Sapieha immediately who interviewed him and accepted him for his underground

seminary.

Most of the students in this wartime underground seminary had been living in

various 'safe houses' in the countryside and traveling to secret locations for

theology classes. Wojtyla's job at the Solvay plant kept him in Krakow where

his life became even more regimented--and compartmentalized. Up at dawn, he

crossed the river to the Archbishop's palace to assist secretly in celebrating

Mass, then he raced off to work at the plant. Late afternoons were devoted to

his religious studies, then rehearsals with the Rhapsodic Theater and the

nightly visit to his father's grave.

In March 1943, Karol finally told members of the Rhapsodic Theater of his

decision. They were stunned; none of them had any idea that he was

contemplating a vocation to the priesthood. While they knew he was devout, he

had never confided in any of them about what must have been an intense inner

conflict between two vocations.

His reticence--or detachment--is exemplified in his friendship with the theater

director, Mieczyslaw Kotlarczyk. Biographer Tad Szulc has described him as

"Karol's intellectual, cultural and thespian mentor, the most important person

in Karol's life after his father and Tyranowski." For an entire year during

the Nazi occupation when all travel was restricted, Karol and Kotlarczyk wrote

letters to each other that Halina Krolikiewicz, an actress in the Rhapsodic

Theater, would smuggle back and forth from Krakow to Wadowice. Karol's letters

were unusually revealing--up to a point. "I surround myself with Books. I put

up fortifications of Art and Learning. I work. Will you believe me when I tell

you that I am almost running out of time. I read, write, learn, pray and fight

within myself. Sometimes I feel horrible pressures, sadness, depression, evil."

What is striking about this letter is that Karol could not share, or would not

share, his great inner conflict. His friend Lorenzo Albacete described

Karol's unusual detachment: "He lived in the most intense solitude, a burning

loneliness, and to some extent it was self-imposed...it all goes back to St.

John of the Cross, to his exhortation of emptying yourself, stripping away

ordinary human supports..."

Halina recalled to us her last conversation with Kotlarczyc before he died: "He

finally revealed how fiercely he had tried to talk Karol out of his decision

to join the priesthood--and how fiercely Karol had resisted him. They stayed up

all night talking. He used every stratagem, even quoting Scripture--multiply

your talents, don't hide your light under a bushel-- but to no avail. What he

was able to accomplish was to persuade Karol to become a priest and not a

contemplative monk hidden away in a monastery. And considering Karol's career

in the Church, this was no small achievement."

After the Nazi roundup in August 1944, when Karol escaped only through hiding

in the basement of his house, Archbishop Sapieha decided that all of his

seminarians would be safer in his residence. So one by one, each of them moved

surreptitiously--sometimes in disguise--past the German troops into the palace

to begin their studies.

Karol was ordained October 3, 1946, in Archbishop Sapieha's private chapel and

soon after celebrated his first Mass in the Wawel Cathedral. The central truth

about Wojtyla's faith is that every conviction which John Paul II would make an

issue central to his Papacy was already in young Karol Wojtyla's heart when he

was ordained a priest . By the age of 26 the structure of his faith had been

shaped--the bones had been set. The themes of suffering, the centrality of

Christ and the belief in God's ongoing supernatural intervention in our lives

were the bedrock. Over the years, these subjects would be elaborated upon,

deepened and refined. Other themes would emerge as his intellectual

horizons widened; these themes would layer, complicate, but never change

these early convictions.

Within a week after his ordination, Wojtyla traveled to Rome to study for his

doctorate in theology. His new mentor, Archbishop Sapieha, recognized Karol's

unusual intellectual gifts and decided that his protege needed a thorough

grounding in moral theology. It was in Rome that Wojtyla encountered Father

Reginald Garrigou-LaGrange, a formidable theologian and the reigning expert on

Thomism. Garrigou-LaGrange would become one of the most important influences on

Karol's spiritual life; he would open Karol up to St. Thomas.

As Karol Wojtyla rose in the Church, he read and wrote voraciously. He

discussed the great theological ideas with students and colleagues. Karol

immersed himself in German phenomenology especially Max Scheler and Edmund

Husserl. Karol embraced the Swiss theologian Balthasar who--like Lubac--urged

his fellow theologians to return to the source of Christianity, to recognize

its stupendous claims about the supernatural. Wojtyla devoured the French

existentialists even though they were not on the approved list. Most

decisively, he grappled with and to some extent accepted St. Thomas Aquinas's

world of immutable and timeless essences--the traditional Catholic theology for the

last 500 years--and a

rational, objective world view very much at odds with his early heroes. Karol

would flirt with but finally reject the 'softer' more experiential world of the

phenomenologists, but not before he borrowed from their contemporary language

of feeling and experience. Some philosophers believe that had he remained in

Lublin as a philosophy professor his life project might have been to marry

phenomenology with Thomism. But others, such as his former student and

colleague, Halina Bortnowska, disagree. As she said to Kwitny:

"Phenomenologists cannot believe in natural law. You can't be a Thomist and a

phenomenologist at the same time."

Though Wojtyla modified Thomism in his work as bishop and cardinal, he drew on

that tradition's moral absolutes. Love and Responsibility, for example,

goes to great lengths to appreciate the complexity of sexual feeling and

response, but basically it accepts the Thomist view that all sexuality must be

generative. The book brought him to the attention of Paul VI, then preparing to

write "Humanae Vitae," whose views on reproduction and birth control would make

it the most controversial encyclical of his papacy--and arguably of this

century. Paul VI was looking for supporters--and unconditional support. He

received it from Karol Wojtyla. Not only did Karol Wojtyla send Paul VI

research materials, he helped draft the encyclical. And then later, during the

firestorm which followed the publication, Karol went public with his support,

praising the encyclical effusively, describing its truths about birth control

as "unchanging." Throughout the next decade Paul VI would take every

opportunity to thank his protege, Archbishop Wojtyla, and to provide

introductions and opportunities.

In 1976, Pope Paul VI invited Wojtyla to give the Lenten lectures in Rome. John

Cornwell, biographer of Pius XII, wrote about the occasion vividly, describing

how in one of Cardinal Wojtyla's lectures he stunned his audience with his dark

apocalyptic vision of the world "as a burial ground....a vast planet of tombs."

His heightened poetic language, filled with images of darkness and light,

showed the influence of his early hero, St. John of the Cross. The remainder of

these lectures explored themes foreshadowing all the major points of Wojtyla's

Pontificate: the centrality of Christ in the history of salvation; the

inviolable dignity of every individual person; the proper relationship between

the creator and creation; the dangerous error of living as if God did not

exist; the value and salvific meaning of suffering.

During these lectures, Cardinal Wojtyla also surprised his audience by

revealing an extremely personal story about his own 'dark night.' This story

has rarely been remarked on, but clearly it has resonated deeply for Wojtyla

and sheds light on intimate corners of his spiritual life. Years ago in Poland,

on the Wednesday of Holy Week, Woytyla had a deep religious experience. As he

talked about it many years later, Cardinal Wojtyla said, with some sadness,

that he tried again and again to recreate this mystical moment but was never

able to. His friend Monsignor Albacete finds this story poignant and moving:

"This man is telling us that he, too, has had the experience of God's absence

and that when he prays he tries to relive that mystical moment of closeness.

But it always goes away from him." It is a familiar story of mystics who early

on in their lives experience a powerful epiphanous moment that they yearn to

experience again, but can't, and must be sustained by the fragments of a memory

for the rest of their lives.

These Lenten lectures were well attended and aroused considerable interest and

comment. When the Papal enclave began after the death of John Paul I, Cardinal

Wojtyla was not altogether the dark horse as the press described him.

Cardinal Deskur's intense behind-the-scenes work on behalf of Wojtyla's

candidacy had considerable history behind it.

On the night of John Paul II's election to the papacy, Bishop Andrzej Deskur

suffered a devastating stroke from which he is still paralyzed. John Paul II

spent much of the first day of his papacy at the bedside of his beloved friend

and supporter. He reflected on Deskur's illness with his former teacher, Stefan

Swiezawski. Wojtyla's private thoughts are startling, but utterly

characteristic. In a conversation with us, Swiezawski recalled their

conversation: "John Paul II spoke about his conviction that the most

important events in his life have been connected to the suffering of his

friends. He believes that Bishop Deskur's stroke was a way of paying for his

election to the papacy and also that his elevation to cardinal was intimately

tied to the tragedy of another friend, Father Marian Jaworski, who had lost his

hand in a railway accident."

Not only do his friends pay, but Monsignor Albacete said to us that Karol

Wojtyla came to see the deaths in his family "as a sacrifice...which gave

direction to his life. Not only did it set him free from family

responsibilities, but the pain was part of the energy which compelled him to

move ahead with his life in the Church. I don't think he has a clear answer and

it is a great mystery before which he bows his head."

What is clear is that the theme of redemptive suffering so central to

the young Wojtyla's spiritual life has only intensified and deepened over the

years. The mystery of suffering has pervaded his thinking, his writing ,his

spirituality from the earliest years onwards. It has also become the defining

theme of his Papacy. While redemptive suffering is, of course, at the heart of

traditional Catholicism, John Paul II has embraced suffering in a way that is

uniquely his own.

As recently as 1994, when John Paul II was furious with the United Nations

over the issues of artificial contraception and abortion, he connected his own

physical suffering and these issues with striking vehemence:

"I understand that I have to lead Christ's church into the Third Millennium

through prayer, by various programs. But I saw that this is not enough, she

must be led by suffering, by the attack 13 years ago. The Pope has to be

attacked. Why now? Why in the Year of the Family? Precisely because the family

is threatened, the family is under attack. The Pope has to suffer, be attacked, so that

every family may see that there is a higher Gospel, the Gospel of suffering by

which the future is prepared...."

John Paul II has written an extraordinary number of encyclicals, letters, homilies. Among his most important encyclicals is his very first,

"Redemptor Hominis" (The Redeemer of Man), in which he laid out the program for

his entire pontificate. It offered a searching examination of man's capacity

for good and evil and asks the question, "Where do we go now?" In a later

encyclical, "Veritas Splendor"(The Splendor of Truth), John Paul II talks

about morality itself--how it attracts us by its beauty. Not surprisingly, a

large number of his writings deal with suffering. "Salvific Doloris" (On the

Christian Meaning of Suffering), for example, is arguably his most personal

statement about the meaning and value of human suffering. The shifting

relations between his fiery core of mysticism and his quest for truth is a

leitmotif running through all of his written work. Most recently, in "Fides et

Ratio" (Faith and Reason), he showed how both are approaches to God.

Faith and Reason is meant to be a challenge to modern-day philosophers. John

Paul II feels that they have lost their way through their obsessions with

arcana and have neglected the large and enduring questions about the great

mystery of life and death. The modern view of reason which limits man to the

visible world can kill faith--but the ache remains. His critics say that Faith

and Reason demonstrates the contradiction it claims to overcome. But for John

Paul II, there is no conflict between God and mind because God is literally

everything.

With all of his writings, his sophisticated discourses, his conversations with

cutting-edge thinkers at his summer retreat at Castle Gondolfo, John Paul II is

a man of mystical persuasions for whom signs and symbols are the alphabet of

God's loving language. The earliest, deepest Polish soil still nourishes him;

the fiery mystical core of his faith still remains intact throughout all the

years, all of his extraordinary encounters with history.

One of the most dramatic and life-threatening of these encounters occurred on

May 13, 1981 just as John Paul II was to announce the creation of an institute

devoted to the study of contemporary science and philosophy. Its purpose was to

provide a dialogue between Catholic theology and modern thought. He never got a

chance to speak. He was shot and almost killed as he triumphantly rode into St.

Peter's Square to make the announcement and to greet hundreds of thousands of

pilgrims who hailed him as the man who would lead the Church into the new

millennium.

And, as he felt his life ebbing away, the Pope remembered what day it was: May

13. On May 13, 1917, three peasant children in Fatima, Portugal claimed to

have seen the Virgin Mary. In successive apparitions on the 13th of the

following months, the apparition warned the children about the disasters that

would befall the world if people did not pray and consecrate themselves to her

"immaculate heart." The children were shown a vision of Hell itself, with its

power and violence ready to envelop the earth, especially through the spread of

Communism. Russia itself had to be consecrated to her heart and be pierced by a

sword. The apparition

revealed a "secret" to the children whose content is unknown, even today,

though apparently locked up in a small box in the Papal chambers. (One of the

'visionaries,' the oldest child, Lucia, is still alive in a cloister.) And, as he felt his life ebbing away, the Pope remembered what day it was: May

13. On May 13, 1917, three peasant children in Fatima, Portugal claimed to

have seen the Virgin Mary. In successive apparitions on the 13th of the

following months, the apparition warned the children about the disasters that

would befall the world if people did not pray and consecrate themselves to her

"immaculate heart." The children were shown a vision of Hell itself, with its

power and violence ready to envelop the earth, especially through the spread of

Communism. Russia itself had to be consecrated to her heart and be pierced by a

sword. The apparition

revealed a "secret" to the children whose content is unknown, even today,

though apparently locked up in a small box in the Papal chambers. (One of the

'visionaries,' the oldest child, Lucia, is still alive in a cloister.)

From that day on, the Pope has never stopped expressing his gratitude to Our

Lady of Fatima. He believes that she saved his life. On the anniversary of the

assassination attempt the next year, he traveled to Fatima to meet the

visionary, Saint Lucia. (Pope Paul VI had refused to meet privately with her to

discourage superstition about the so-called "secret.") John Paul II has

brought his blood-stained sash to the feet of the statue of the Virgin at

Fatima. He has placed the bullet of the would-be assassin in her crown. He has

also consecrated Russia to her Immaculate Heart, convinced that it would hasten

the end of the Soviet menace to world peace. The institute that was to be

announced that day exists and it has campuses all over the world. Its patroness

is the Virgin of Fatima, and her statue adorns its academic halls everywhere,

by order of the Pope.

Philosophers and theologians with modern sensibilities cannot understand this

man who, though intellectually one of them, seems to behave and be moved by a

piety associated with the uneducated masses or with those who fear modern life

and seek consolation in the extraordinary, in the supernatural, living in a

world of signs and prophecies. The Pope entrusted the life of a sick friend, a

woman Polish doctor, to the prayers of Padre Pio, the Franciscan friar in

southern Italy who bore in his body the "stigmata" of the crucified Jesus

bleeding profusely at Mass and who was said to be able to be in two places at

the same time, when he wasn't battling Satanic apparitions in the form of

savage beasts.

Karol Wojtyla seems to be seeking to live several lives: the life of a thinker,

at home in the world of concepts and scientific theories, the life of a mystic

of the sublime and the ineffable, and, the life of a peasant child unable to

read or write. How is this possible? How can such a contradiction be

justified?

Marina Warner, the writer and Marian expert, talked with us about this

"apparent contradiction:"

"The Pope is a populist and he is a pioneer in this. Popes usually come from

the elite. They tend to be very skeptical about the faithful who need to be

controlled and to be told what to think. So he's reversed that direction. He

likes it when there's a new vision, when the bleeding statue at Trevitavecia

wept tears of blood several years ago, and he's prepared to make them into new

pilgrimage sites--he wants to create a new sacred geography throughout the

world. All of this provokes some of the most intense wrigglings and writhings

inside the theological community and among those cardinals who are embarrassed

by his apocalyptic, millennial and generally miraculous attitudes. But these

intellectual Christians forget the deeply irrational mystical core of

the Christian religion. The mystery of the Eucharist, the absolute central

doctrine of the Incarnation, the Virgin Birth, the idea that a woman would bear

a child without any male seed at all--the miraculous is installed at the very

heart of the faith! It is axiomatic of the faith because faith is about

believing in something that is difficult to believe in. It is about wonder. So,

in a sense, the Pope is actually reintegrating something that is traditional and

central to the self-presentation of the Church."

So, finally, the question is: Is this a contradiction characteristic of this

man, or is it not at the very heart of the Christian message, namely, that the

God of the sublime, the exalted, transcendent, living in "unapproachable

light," is the same God incarnate in the Jewish man, born to a Jewish teenager?

Is Karol Wojtyla not, after all, simply trying to be faithful to the

contradiction--or the paradox, if you will--at the heart of the Christian

faith?

Modernity's complex and often contradictory cultural impulses must wrestle with

the coherence of this man's world view and, of course, his very faith. He is

praised for the simple consistency of his moral outlook. And yet, so often, a

certain pride, even a dangerous smugness attaches itself to 'counter-cultural'

pronouncements. Is this the case for Karol Wojtyla?

Certainly the tension between faith and culture has been with the Church since

the beginning and no Pope, even one so possessed of so powerful a vision as

this one, will ever completely reduce that tension. There is a great danger in

a prophet who trims his message to the demands of the day, but there is another

danger in a prophet who fails to listen...

Is Karol Wojtyla a prophet?

If the contradictions in his life and faith are due to something that he has

failed to grasp, Pope John Paul II has been a tragic figure indeed. But if they

are due to something we fail to grasp, then the inability to understand him has

been our tragedy.

home |

discussion |

interviews |

his faith |

testimonies on faith |

the church and sexuality |

the pope and communism

biography |

anecdotes |

his poems |

"abba pater" |

encyclicals |

video excerpt |

tapes & transcripts |

synopsis |

press |

teachers' guide

FRONTLINE |

pbs online |

wgbh

web site copyright WGBH educational foundation

|  |