|

For more than two hundred years after a Virginia newspaper ran the first report

about the President and "Dusky Sally," the story linking Thomas Jefferson and

Sally Hemings persisted underground--told around the tables of African-American

families, rumored around academic history departments. Occasionally, the story

re-surfaced: In 1873, Sally's son Madison told a newspaper reporter it was

true; a hundred years later, a U.C.L.A. historian published a best-selling book

arguing for the relationship. But it never took hold. As recently as 1996,

Joseph Ellis included a "Note on the Sally Hemings Scandal" in his National

Book Award-winning Jefferson study; it read like an epitaph for a story

that had tottered on the ropes for most of its public life:

Within the community of Jefferson specialists, there seems to be a clear

consensus that the story is almost certainly not true. . . After five years

mulling over the huge cache of evidence that does exist on the thought and

character of the historical Jefferson, I have concluded that the likelihood of

a liaison with Sally Hemings is remote. (Read Ellis's full "Note")

After the publication of the DNA evidence, Ellis, who wrote of himself as "one of those students of Jefferson who previously questioned the possibility" of a relationship with Hemings, made plain his belief that the matter had been "proved beyond any reasonable doubt". Many of the Jefferson

historians who had written so dismissively of the Hemings story--often cruelly

so--were no longer alive. But what did it mean that so

many of these eminent historians had been so decidedly wrong for so long? Now, a new generation of historians has largely accepted the truth of Jefferson-Hemings, and moved on to ask a new set of questions about the nature of the relationship and its significance. But what can be learned from the two hundred-year history of the Jefferson-Hemings story before DNA--and before the more sympathetic reconsideration of the story that followed?

One thing is clear: early in this history, Jefferson's "secret" became a lie about Jefferson's

nephews, the Carrs, having fathered the Hemings children. The lie

about the Carrs was invented by Jefferson's white relatives, and passed along

by generations of historians who seemed to take little interest in proving the

matter one way or another. How did this happen? Why was the oral history of

one side of a family listened to as truth and the oral history of another side of that family dismissed as gossip and libel?

Why did it take outsiders to the historical profession--a law

professor and a retired doctor, among others--to finally untangle truth from lie, and to spill the original secret?

In this report, FRONTLINE re-reads the long record of claims and counterclaims on Jefferson and Hemings, illustrating the major episodes in this history with text and special video

reports. Retrace the tortuous trail of this story in greater detail on FRONTLINE'S "History of A Secret" chronology.

![It is well known that [Jefferson] keeps, and for many years past has kept, as his concubine, one of his own slaves. Her name is SALLY. . . By this wench Sally, our president has had several children. . . James Callender Richmond Recorder September 1, 1802](../art/sv4q1.gif) In 1802, James Callender, a Scottish-born journalist infamous for his character

assassinations of a number of the Founding Fathers, turned his poison pen on

then-president Thomas Jefferson. Callender reported that Jefferson kept a

slave "concubine," named Sally at Monticello, and "by this wench Sally, our

president has had several children." He added of Sally Hemings: "The African Venus is said to officiate,

as housekeeper at Monticello." Late in 1802, Callender published additional

information that he believed confirmed his initial report about Hemings. Addressing himself to skeptics, he wrote: "Mr. Jefferson's Sally and their children are

real persons. . . she is an industrious and orderly creature in her behaviour,

but her intimacy with her master is well known. . . she is treated by the rest

of the house as one much above the level of his other servants."

In 1802, James Callender, a Scottish-born journalist infamous for his character

assassinations of a number of the Founding Fathers, turned his poison pen on

then-president Thomas Jefferson. Callender reported that Jefferson kept a

slave "concubine," named Sally at Monticello, and "by this wench Sally, our

president has had several children." He added of Sally Hemings: "The African Venus is said to officiate,

as housekeeper at Monticello." Late in 1802, Callender published additional

information that he believed confirmed his initial report about Hemings. Addressing himself to skeptics, he wrote: "Mr. Jefferson's Sally and their children are

real persons. . . she is an industrious and orderly creature in her behaviour,

but her intimacy with her master is well known. . . she is treated by the rest

of the house as one much above the level of his other servants."

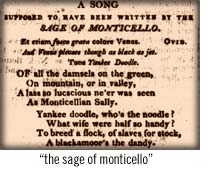

Jefferson never responded publicly to Callender's charge--or to any of the

rumors that surfaced before and after Callender's 1802 articles. But, for

years, Jefferson's detractors and political enemies among the Federalists made

use of the story to defame him. A number of popular rhymes lampooned the

president and "Dusky Sally." Politically, however, Callender's story never had much effect

on Jefferson, who easily won a second term as president in 1804 in a landslide

election which scarcely included mention of the Hemings story.

Callender, perhaps, suffered the worst of it, bitterly disappointed that

Virginians did not turn on Jefferson as a result of his reports. "Callender

misunderstood white attitudes toward interracial sex in Virginia" historian

Joshua Rothman concluded, "and thus failed to foresee that although his allegations might

embarrass Jefferson and his white family, they were unlikely to provoke any

larger consequences for his career or standing." Why this might be the case,

Rothman found, had everything to do with Callender's manner of relating the

story -- he was criticized for his immodest and "graceless" peek behind the

curtain of a Virginia gentleman's private home.

Rothman concluded: "Callender never understood that in Virginia and in other parts of the South

there were honorable and dishonorable ways of sharing information about the

interracial sexual affairs of elite men. Consequently, he never foresaw that

even people who believed Jefferson's sexual behavior was less than admirable

might very well feel that Callender's own behavior in publishing the story was

at least distasteful."

In July of 1803, Callender stumbled drunk into Richmond's James River, and

drowned, taking with him to the river-bottom much of the drive behind the

public pursuit of the story. Callender did not get

everything right about the story--he passed along a rumor about a daughter of

Sally Hemings (presumably fathered by another Monticello male) that was

demonstrably false; and persistently mentioned the couple's first child "Tom"

whose connection to Monticello has never been firmly established. But the

truths Callender did report would not be accepted, so freighted were they with

the baggage of Callender's own bad character: Even a modern-day writer disposed to

believe the core of Callender's report could not help but brand Callender "a despicable

individual ruled by venom and racism." Callender's political entanglements

with Jefferson and others he wrote about also made him easier to dismiss.

Historians who may have been uncomfortable with the story in the first place,

could write off Callendar's reports as the work of an inveterate scandalmonger,

a drunk fresh from a prison term for libel and sedition, or a frustrated

political hack who pursued a vendetta against Jefferson after the president

refused to be blackmailed into appointing him Postmaster of Virginia.

In July of 1803, Callender stumbled drunk into Richmond's James River, and

drowned, taking with him to the river-bottom much of the drive behind the

public pursuit of the story. Callender did not get

everything right about the story--he passed along a rumor about a daughter of

Sally Hemings (presumably fathered by another Monticello male) that was

demonstrably false; and persistently mentioned the couple's first child "Tom"

whose connection to Monticello has never been firmly established. But the

truths Callender did report would not be accepted, so freighted were they with

the baggage of Callender's own bad character: Even a modern-day writer disposed to

believe the core of Callender's report could not help but brand Callender "a despicable

individual ruled by venom and racism." Callender's political entanglements

with Jefferson and others he wrote about also made him easier to dismiss.

Historians who may have been uncomfortable with the story in the first place,

could write off Callendar's reports as the work of an inveterate scandalmonger,

a drunk fresh from a prison term for libel and sedition, or a frustrated

political hack who pursued a vendetta against Jefferson after the president

refused to be blackmailed into appointing him Postmaster of Virginia.

Callender proved thoroughly vulnerable to attack, but, Annette Gordon-Reed

reminds us, historians exploited Callender's vulnerabilities to undermine the reliability of a story they did not want to believe was true: "To discredit a

Jefferson-Hemings liaison, it is necessary to discuss James Callender as though

he invented the story and as though none of Callender's contemporaries looked

into the matter and, in their view, substantiated the charges," Gordon-Reed

writes in her exhaustive and rigorous analysis of the history of the story.

"This characterization makes it easier to present the story as something so

fantastic and without foundation that it is unworthy of a second thought."

In the years following the Callender story, rumors persisted about Jefferson

and Hemings, but they did not again come into public focus, and they forced no

explicit comment from Jefferson. By the early 1830's, both Jefferson and

Hemings were dead. By the 1860's, a number of people added comment on the

story. One seemed to offer confirmation: John Hartwell Cocke, a close friend

of Jefferson's, mentioned the former president's "notorious example" in a

discussion of sex across the color line. But a growing number of

commentators--relatives, a former Monticello slave

overseer--began to point the finger away from Jefferson to his nephew, Peter

Carr, as the father of Sally Hemings's children. The story about Peter Carr would then be written into history as the last word on

the subject for more than a century.

Just as the Peter Carr story was being set in stone as true, however, an elderly black man in Ohio asked by a newspaper reporter to tell the story

of his life, quietly made a surprising claim: that Thomas Jefferson was his father.

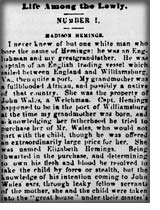

![[In Paris], my mother became Mr. Jefferson's concubine, and when he was called back home she was enciente (sic) by him. Soon after their arrival [back in Virginia] she gave birth to a child, of whom Thomas Jefferson was the father... She gave birth to four others, and Jefferson was the father of all of them... Madison Hemings Pike County Republican (Ohio) March 13, 1873](../art/sv4q2.gif) In 1873, as part of a series of newspaper articles on interesting lives of

blacks living in southern Ohio, a writer named S.F. Wetmore interviewed Madison

Hemings, then 68 years old and living the life of a retired, free man. In

response to Wetmore's questions, Madison told the story of his life, including:

what he knew of his great-grandfather, a white sea

captain who "bore the name of Hemings" and his mother's

earliest owner, John Wayles; and what he remembered about his first and only owner, Thomas Jefferson ("I

knew more of his domestic than his public life during his life time.").

Madison's most controversial claims were about his mother, Sally Hemings, however, and

her links to Jefferson: In Paris, Madison claimed:

In 1873, as part of a series of newspaper articles on interesting lives of

blacks living in southern Ohio, a writer named S.F. Wetmore interviewed Madison

Hemings, then 68 years old and living the life of a retired, free man. In

response to Wetmore's questions, Madison told the story of his life, including:

what he knew of his great-grandfather, a white sea

captain who "bore the name of Hemings" and his mother's

earliest owner, John Wayles; and what he remembered about his first and only owner, Thomas Jefferson ("I

knew more of his domestic than his public life during his life time.").

Madison's most controversial claims were about his mother, Sally Hemings, however, and

her links to Jefferson: In Paris, Madison claimed:

"My mother became Mr. Jefferson's concubine, and when he was called back home

she was enciente (sic) by him. Soon after their arrival [back in Virginia] she

gave birth to a child, of whom Thomas Jefferson was the father. . . She gave

birth to four others, and Jefferson was the father of all of them. . . "

(Read the full memoir)

Though historians found Madison sufficiently trustworthy on all sorts of matters (the Wayles family, domestic life at Monticello), they would

attack and denigrate him for his claims about his mother and

Jefferson. A week after the publication of Madison's testimony, John A. Jones,

the editor of the Waverly Watchman, a rival to S.F. Wetmore's Pike County

Republican--bitterly dismissed Madison as a puppet of Wetmore or as just

another "colored" person laying claim to illustrious parentage, "rather than to

acknowledge that some field hand, without a name" had parented him.

Though historians found Madison sufficiently trustworthy on all sorts of matters (the Wayles family, domestic life at Monticello), they would

attack and denigrate him for his claims about his mother and

Jefferson. A week after the publication of Madison's testimony, John A. Jones,

the editor of the Waverly Watchman, a rival to S.F. Wetmore's Pike County

Republican--bitterly dismissed Madison as a puppet of Wetmore or as just

another "colored" person laying claim to illustrious parentage, "rather than to

acknowledge that some field hand, without a name" had parented him.

In December of 1873, Wetmore tracked down Israel Jefferson, another man who

had been a slave at Monticello during Jefferson's time, and published his

memoir. Among other things, Israel corroborated Madison's statements about

Sally Hemings and Jefferson. In the pages of that same day's newspaper, however, Israel was attacked as untrustworthy by Thomas Jefferson Randolph, the

president's grandson, who denied the charge, asking rhetorically,

"What is the meaning of such calumnies?"

In 1874, James Parton, a prominent nineteenth-century Jefferson biographer,

dismissed Madison Hemings as "misinformed" and repudiated the claim of a

Jefferson-Hemings relationship as "impossible." In the same passage, Parton

endorsed the theory that one of the Carr brothers had fathered Sally Hemings'

children. What was Parton relying on for this conclusion? A report of a

conversation between Thomas Jefferson Randolph and Henry Randall, an

earlier Jefferson biographer and descendant of the president, and a letter

from Ellen Coolidge, the president's granddaughter. "Nowhere can historians'

double standard for assessing evidence in the Jefferson-Hemings controversy be

plainer than in the promotion of the idea that one of Thomas Jefferson's

nephews, Samuel Carr or Peter Carr, was the father of Sally Hemings's

children," writes Annette Gordon-Reed.

"The chief qualifications that the Carr brothers have for this designation are

(1) neither one of them was Thomas Jefferson, (2) neither seems to have been a

very good guy, so that they can be cast as having engaged in miscegenation, and

(3) neither man means anything to the American public."

(Read Gordon-Reed's full discussion of historian's treatment of Madison's

testimony)

The word of two of Jefferson's slaves, Madison Hemings and Israel Jefferson,

was measured up against the that of two of the president's grandchildren--and,

Gordon-Reed makes clear, the slaves came up short. "What we are left with is a situation

where the oral history of one family is pitted against the oral history of

another family. It is black against white, under circumstances where whites

for the most part have controlled the assemblage and dissemination of

information."

Other lines of attack on Madison's testimony stressed that Madison was lied to

by his mother, Sally Hemings. In this vein, historian Douglas Adair writes:

"No matter how sympathetic one is to Sally, one must conclude that she is not

trustworthy about Jefferson's relations with her. We may pity her and even

understand why she lied, but on this topic we cannot trust her." (Adair then

offers one of the most elaborate imaginings of the relationship between

Peter Carr and Sally Hemings ever recorded.) In his later attack on Madison's memoirs, Dumas Malone, Jefferson's

eminent 20th century biographer, sets his sites not on Madison himself ("who

appears to have been an estimable character"), but on S.F. Wetmore, who

Malone claims, clearly "solicited and published [the story] for a

propagandistic purpose."

Other lines of attack on Madison's testimony stressed that Madison was lied to

by his mother, Sally Hemings. In this vein, historian Douglas Adair writes:

"No matter how sympathetic one is to Sally, one must conclude that she is not

trustworthy about Jefferson's relations with her. We may pity her and even

understand why she lied, but on this topic we cannot trust her." (Adair then

offers one of the most elaborate imaginings of the relationship between

Peter Carr and Sally Hemings ever recorded.) In his later attack on Madison's memoirs, Dumas Malone, Jefferson's

eminent 20th century biographer, sets his sites not on Madison himself ("who

appears to have been an estimable character"), but on S.F. Wetmore, who

Malone claims, clearly "solicited and published [the story] for a

propagandistic purpose."

Just a few years after the publication of his memoirs, Madison Hemings died at

his home in Chillicothe, Ohio. With the Carr brothers firmly in place as the

fathers of the Hemings children, the story slipped into the back pages of

newspapers and into the quiet realm of settled history, where it remained

largely untouched through the middle of the next century.

In the early 1950's, the story returned--some say as part of a larger re-examination of race in America during the early years of the civil rights movement. A number of primary sources key to piecing together the

Jefferson-Hemings story were "re-discovered" in archives around the country: Henry Randall's 1868 lett to

James Parton turned up in some papers at Harvard; Jefferson's Farm Book, with

detailed notes on his slaves, was rooted out from items donated to the

Massachusetts Historical Society in 1898; and the testimony of Madison Hemings,

which once so-incensed Jefferson's grandson and his 19th century biographer--but then went missing--was unearthed by an archivist at the Ohio State

Historical Society. Several popular accounts of the Jefferson-Hemings story

were published in black magazines or scholarly journals of "negro history," but

the story gained little currency with Jeffersonians. In 1960, Merrill Peterson,

the great University of Virginia historian, offered this summary of the fate of

the story from Madison Hemings's time to his own:

Upon the flimsy basis of oral tradition, anecdote, and satire, [some] avowed

their belief in Jefferson's misecegenation. . . [but] when there was little but

Jefferson's own history and the memories of a few Negroes to sustain it, the

legend faded into the obscure recesses of the Jefferson image. . .

And, here, the story would remain, until a biographer with a special interest

in the paradoxical private lives of "great men" turned her sites on Thomas

Jefferson. She soon found herself at Monticello asking questions about Sally

Hemings.

In February of 1974, Fawn Brodie published a book which did something that no

one in the history of the story had ever done in such elaborate depth and

detail: Brodie wrote Sally Hemings into the life of Thomas Jefferson--not as a

footnote about a scandalous "miscegenation legend," or "campaign lie," but as

the subject of one of the president's serious lifelong romantic passions, and

as the mother of a number of Jefferson's children. Brodie's controversial

psycho-biographical methods focussed on Jefferson's conflicted "head and

heart," and his capacity for denial and secrecy in his emotional life. "The

extent to which Jefferson kept Sally Hemings and her children relatively

anonymous in his Farm Book would seem to be symbolic of his entire

relationship with her," she wrote.

In February of 1974, Fawn Brodie published a book which did something that no

one in the history of the story had ever done in such elaborate depth and

detail: Brodie wrote Sally Hemings into the life of Thomas Jefferson--not as a

footnote about a scandalous "miscegenation legend," or "campaign lie," but as

the subject of one of the president's serious lifelong romantic passions, and

as the mother of a number of Jefferson's children. Brodie's controversial

psycho-biographical methods focussed on Jefferson's conflicted "head and

heart," and his capacity for denial and secrecy in his emotional life. "The

extent to which Jefferson kept Sally Hemings and her children relatively

anonymous in his Farm Book would seem to be symbolic of his entire

relationship with her," she wrote.

It was a kind of automatic denial, in the written record, that this slave woman

and her children were important to him. . . The denial was accepted too, though

in a different fashion, by the slave who was genuinely loved. Here the slave

was peculiarly deprived of the right to, and even the desire for,

emancipation, because freedom meant loss of the love relationship.

(Read the full excerpt from the Brodie biography).

Brodie was attacked for "putting Jefferson on the

couch" and for reading symbolic meanings into Jefferson's writings in a way that historians could not

accept. Interestingly, however, historian Winthrop Jordan wrote about the

Jefferson-Hemings relationship several years earlier in a book that won the

Bancroft Prize, the highest honor in the historical profession. And Jordan's

discussion of the matter seemed to rely just as heavily on psychological

"evidence". In an important passage of his 1968 book, Jordan writes:

It is possible to argue that attachment with Sally represented a final happy

resolution of [Jefferson's] inner conflict. . . Sally Hemings would have become

Becky Burwell [an early romantic attachment] and the bitter outcome of his

marriage erased. Unsurprisingly, his repulsion toward Negroes would have been,

all along, merely the obverse of powerful attraction. . .

(Read the full

excerpt from Winthrop Jordan).

But Jordan did not endorse the idea of a love relationship between Jefferson and Hemings; he merely laid out a possible argument for how it could be true. Then, he quickly pulled back from it, saying the matter was not significant even if it were proved true: "The question of Jefferson's miscegenation, it should be stressed

again, is of limited interest and usefulness even if it could be satisfactorily

answered." Fawn Brodie went much further when she passionately argued for the

truth of a lifelong passionate romance between the Jefferson and Hemings. Though her chapter on Sally Hemings was but one of over thirty, this is what brought

her popular renown--by the late Spring of 1974, Brodie's Jefferson was into its

third printing and had secured a regular place on the New York Times bestseller

list. But this is what also drew fire from book reviewers and

historians who accused her of "groping" for

evidence, and engaging in "historical gossip."

Just as in earlier eras attacks on the story focused on the messengers-- James

Callender; S.F. Wetmore and Madison Hemings-- the "modern" era of the story was

marked by an attempt to make the story seem like the singlehanded re-invention

of Fawn Brodie. Historian John Chester Miller wrote in a characteristic passage: "The 'Sally Hemings' story had, in fact, long been dismissed

as a mere political canard until it was revived, refurbished, and given the

gloss of verisimilitude by Ms. Brodie." (Read the the full excerpt)

Garry Wills, the journalist and historian, penned

perhaps the most intensely personal of the attacks on Brodie. His review of

her Jefferson biography began cuttingly:

Two vast things, each wondrous in itself, combine to make this book a

prodigy--the author's industry, and her ignorance. One canonly be so

intricately wrong by deep study and long effort, enough to make Ms. Brodie the

fasting hermit and very saint of ignorance.

(Read Wills's full review of

Brodie's book).

Wills took particular issue with Brodie's characterization of the relationship

as one of love. His Sally Hemings, instead, was, at best, "like a healthy and

obliging prostitute, who could be suitably rewarded but would make no

importunate demands. Her lot was improved, not harmed, by the liaison." Much

of the "modern" history of the story, in fact, would be focussed on the nature

of the relationship--locating it on the spectrum from love to rape.

If Fawn Brodie wrote Hemings into the story of Jefferson's life in a way that

had never before been done, Barbara Chase-Riboud, in her 1979 book, Sally

Hemings: A Novel, treated Hemings herself as the subject, giving flesh, blood,

and psychology, where the historical record could only say she was "mighty

ne'er white." Chase-Riboud also offered the first fully-realized portrait of

the relationship between Jefferson and Hemings, with all of the psychological

complexity and texture of relations between any two people who felt

passionately for one another. Chase-Riboud even dared to imagine the first

sexual contact between the two:

I bent forward and pressed a kiss on the trembling hands that encompassed mine,

and the contact of my lips with his flesh was so violent I lost all memory of

what came afterward. . . At once he left me, surveying me from above with the

yes of a man afraid of heights scanning a valley from a tower. Then his body

tensed and rushed toward me as if he ahd found a way to break his fall. Thus

did Thomas Jefferson give himself into my keeping.

Chase-Riboud relied heavily on Brodie's biography, and other academic sources,

blending historical documents into her historical fiction. Like Brodie,

Chase-Riboud may have most offended Jeffersonians simply by being popular--her

novel became a best-seller. When CBS announced plans to adapt the book for a television mini-series, the Jefferson "establishment," an informal coalition of eminent historians, descendants, and Monticello staff, rallied as never before to make sure the mini-series never aired. Jefferson biographer Dumas Malone advised the CBS President Robert A. Daley that he should "abandon" a series based on "a tawdry and unverifiable story." Malone added:

If you do go ahead with the project, I would urge you to make it absolutely clear that you are presenting fiction. . . I do this not only on my own account, but in behalf of all persons who are concerned with the preservation and presentation of the history of our country.

Later in January of 1979, historian Merrill Peterson followed up on Malone's letters, writing the CBS Chairman William Paley to reconsider lending his network's good name to "vulgar sensationalism masquerading as history." By February of 1979, Malone had gone public with his concernes, telling a Washington Post reporter: "Scandal and sex can be exploited to great financial advantage. The public will always believe the story. You can never get it back. You can never stop it."

By December of 1979, plans for the mini-series were dead. Virginius Dabney, a Jefferson descendant and vocal critic of the Brodie biography and the Chase-Riboud novel wrote to Malone to say CBS "had lost all enthusiasm" for the story. "Enough damage has been done by Brodie and Chase-Riboud without TV," Dabney added. Though Dabney congratulated Malone for his role in killing the mini-series, Malone expressed regret that the matter had attracted so much publicity and worried that this would might not be the last effort to popularize the Hemings story: "We must keep our fingers crossed. Eternal vigilance will be necessary."

For more than 40 years, Dumas Malone had made Thomas Jefferson his life's work. Malone's six-volume Jefferson biography remains the most majestic and comprehensive source on Jefferson's life ever written. For much of his career, Malone seemed not to give much consideration to the Hemings story. When he finally wrote of the story, it was under the heading, "The Miscegenation Legend." He believed Madison Hemings had been lied to by his mother, or had been the unwitting tool of S.F. Wetmore, the reporter who recorded Madison's memoirs. Malone considered the Hemings story a nuisance, a lie, and a libel on a great president. But, at age 92, in one of the last interviews of his life, Malone told a New York Times reporter that he felt Jefferson and Hemings might have had sexual contact "once or twice." This is what surprised and dismayed Barbara Chase-Riboud, and others about the Jefferson "establishment" view of the story. That they were willing to accept Jefferson as a casual rapist of young slave women rather than accept that he may have had any sort of intimate relationship with Sally Hemings.

After 200 years of secrets, lies, and denials, a retired doctor named Eugene

Foster published the results of his DNA study. He compared the blood of Sally

Hemings's descendants with the descendants of Thomas Jefferson's uncle; a match

was found--and with it an answer to a persistent and enduring question about the paternity of Sally Hemings's children. Thomas

Jefferson almost certainly fathered children with his beautiful mulatto slave. Even historians

who had earlier passionately denied that a relationship between Hemings

and Jefferson could have existed were forced to accept a truth that just a few years earlier had seemed remote. The

news came as vindication to those who had long maintained the story and paid a

price for doing so. From Fawn Brodie to the novelist Barbara Chase-Riboud to

the scientist Eugene Foster--and from generations of African-American families who passed along their oral history--outsiders kept the story alive.

What did all of this say about the character of Thomas Jefferson? What did the long history of claims and counterclaims about "Dusky Sally" say about the way history is written? In March of 1999, Professors Jan Lewis

and Peter Onuf quickly organized a conference at the University of Virginia inviting "historians to reflect upon and begin attempting

to explain the significance of the liaison between Thomas Jefferson and Sally

Hemings." The organizers described it as a forum for a number of academics who

had assumed the truth of the relationship before the DNA but had "not bothered

to publish their thoughts."

In January of 2000, The Thomas Jefferson Memorial

Foundation--for most of this century, a careful guardian of the Jefferson icon-- issued the "Report of the

Research Committee on Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings" which largely corroborated Dr. Foster's findings. The report stated:

In January of 2000, The Thomas Jefferson Memorial

Foundation--for most of this century, a careful guardian of the Jefferson icon-- issued the "Report of the

Research Committee on Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings" which largely corroborated Dr. Foster's findings. The report stated:

"Although paternity cannot be established with absolute certainty, our evaluation of the best evidence available suggests the strong likelihood that

Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings had a relationship over time that led to the

birth of one, and perhaps all, of the known children of Sally Hemings."

The report came like final confirmation that the story that the Hemings descendants had always known to be true could finally be acknowledged at Monticello, the place where it began. Now a new generation of historians, no longer exhausting itself in the exercise of denial, has begun to take up the challenges that have come with the story to deepen their understanding of Jefferson, his time, and lives of the men and women who were his slaves.

More than twenty years earlier, the greatest Jefferson scholars in the country had banded together to convince television executives not to dignify the Hemings story with any network airtime--and, if they did, to do so only after making plain that the story was pure fiction. Screenwriter Tina Andrews told FRONTLINE

that she had tried for 15 years to get a Sally Hemings story made, but was frequently told by skittish executives

that television is advertiser based, and the public might

not be ready to accept the story. After Dr. Foster's

report was made public, Andrews says, her phone rang off the hook with producers and executives who had a sudden new resolve to tell Hemings's story. In a telling postscipt to the long history of this story in American life, the television network mini-series Sally

Hemings: An American Scandal aired in February of 2000. The two nights worth of programs were among the network's highest rated programs of the year.

You'll need either QuickTime or RealPlayer G2 (or 7) to view these clips.

home ·

view the report ·

is it true? ·

the jefferson enigma ·

the slaves' story ·

mixed race america

home ·

view the report ·

is it true? ·

the jefferson enigma ·

the slaves' story ·

mixed race america

special video reports ·

discussion ·

links ·

quiz ·

chronology ·

gene map

interviews ·

synopsis ·

tapes ·

teacher's guide ·

press

FRONTLINE ·

pbs online ·

wgbh

web site copyright WGBH educational foundation

|