Bill Clinton's

presidency ran into trouble only hours after his inauguration. In the first

week alone, the new president was developing strained relations with both

Congress and the armed forces over his decision on gays in the military, and he

had to withdraw his choice for Attorney General, Zoe Baird. The problem was

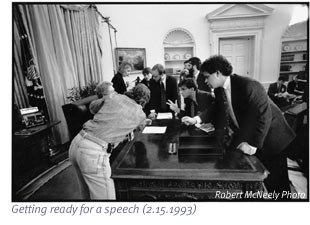

compounded by Bill Clinton's management style -- he loved presiding over long,

unstructured, free-for-all meetings.

Myers: It was hell. It was hell. And the thing about the Zoe Baird

question was that I don't think anybody -- I mean everybody, myself -- let me

just say, I missed it. You know, I said, "Yeah, this is a problem. You know,

it's going to take some explanation. I think Zoe's going to have a little crow

to eat on this."

I did not anticipate the reaction from not just the media, but there was some

visceral nerve that it touched in the country. You know, here we've elected

this kind of populist president and the first thing he does is appoints a woman

who is making $500,000 a year as counsel to a big corporation and she doesn't

even pay Social Security taxes on her household help. Not only that, they are

illegal.

And she's going to be the Attorney General?

Myers: -- and she's going to be the Attorney General.

Panetta: What tends to happen in the White House and in Washington is if

you allow a vacuum to be created in which you're not delivering your message, a

positive message, then into that vacuum will come some very controversial

issues that then will dominate your agenda. And I think that's the lesson that

they learned, is that in that first instance, in the failure to kind of have

some continuing messages that they were going to deliver as a new president to

the United States, what happened is that both the Congress and the press made

gays in the military the first issue. And they suddenly found themselves with

a controversy they had to confront. I think that was in part a problem with

experience in the White House.

Myers: And then Tom Friedman had asked him about it. He sat down with

the New York Times. And barring any other really big news, the

Times led the paper with it. And then everybody else sort of got

going and it was -- your first reaction is, "This is a new administration,

there's a lot going on in the world, this is really what we're going to focus

on now?" And people often say to me, "Why'd you make gays in the military your

first, big issue?" We didn't do it, we just couldn't figure out how to stop

it.

Emanuel: It became a priority. It became a dominant part of our first

days of our administration. It should not have been. It was mishandled. On

the other hand, it is what it is, and that's governing. My point is [the

media] brought it up. We didn't bring it up. It was a question he got asked

at a press conference. He answered it. And then it became our priority.

Emanuel: It became a priority. It became a dominant part of our first

days of our administration. It should not have been. It was mishandled. On

the other hand, it is what it is, and that's governing. My point is [the

media] brought it up. We didn't bring it up. It was a question he got asked

at a press conference. He answered it. And then it became our priority.

Lake: The meetings that I can recall between the president and the JCS

[Joint Chiefs of Staff] -- and there were a number of them -- were never really

contentious so much as, again, trying to work this thing through. And they

were always respectful. I know they weren't happy with it. This was not an

issue that we were asking to address right away. People sometimes ask me, "How

come you chose that, of all issues, to address first?" Well, we didn't choose

it first. We were working -- wanting to work mostly on Bosnia, Haiti, these

other issues, and to set an agenda for the next four years. But it was very

clear that, especially on the Hill, they were not going to let go of this

issue, and if we didn't come up with some formula, then it was going to be

jammed up our noses from the Hill.

Panetta: What I noticed, though, was that in some of the meetings that I

was asked to attend as budget director, that the meetings were often

unstructured and would go on, literally, for an hour and a half, two hours,

more than two hours, in which there was no kind of presentation of "These are

the issues, these are the options," kind of approach. It was all kind of

everybody have your say. And there were people from all over the White House

that were in these meetings. I mean, there were kids that, frankly, had no

business being there, who were sitting in on these meetings.

And so, rather than kind of, a meeting -- you're dealing with the President of

the United States, it's precious time -- he goes into these meetings and it

becomes, frankly, almost a BS operation, in terms of everybody kind of

expressing different viewpoints. Now, you know, I think he kind of enjoyed the

free discussion in those meetings. But it took an awful lot of time away from

the President of the United States. So that was problem number one.

Problem number two was that there never seemed to be closure, and when you've

got a president who's got to make a decision, there's got to be closure. In

other words, the president makes a decision, that's it. You move on. There

oftentimes seemed to be meetings that said, "Oh, we think the president is

going to come down on this decision," and yet, you know, a couple of days

later, it would be changed. So there was no closure.

Stephanopoulos: And it has become easy to caricature, these all night

bull sessions that are like college seminars and undisciplined staff who are

running around like a bunch of kids after a soccer ball, all going to the ball

at the same time. Easy to caricature. On the other hand, one of the other

strong feelings I remember is thinking, "Boy, in some ways this is the way it

should be." Not the all night nature, but the serious discussion of the earned

income tax credit and agriculture policy, and what is the right and best use of

our education dollars.

I still also believe that we were going about things intellectually in a very

serious way. We were blind to the importance of structure -- and actually, we

didn't have enough respect, deep, deep in your bones respect for the office

itself. ... There's something important about going about the work of the

White House in a more formal way, even if it feels a little stilted at the

time.

Reich: I remember I used to get calls from the White House. My

assistant over in the Labor Department would say, "The White House wants you to

do this," or "The White House wants you to go over here. The White House wants

you to go to California." And I discovered that there was not a White House

that wanted me to do anything. There were usually kids about 30 or 32 years

old that wanted me to do something. So I began asking my assistant, "Find out

how old the person is who wants me to go. If the person is under 40, I'm not

going to go. Over 40, then we're going to find out if the president really

wants me to do something."

Shalala: Someone needed to say, "Wear suits. We've got to have a limit

to the number of people who have access to the president, we have to have a

systematic policy and budget development process."

But I liked the youthful enthusiasm that the Clinton campaign came in with. I

think it allowed us to dream big and while we stumbled during that first year,

in some ways, it was worth it, because it meant that we didn't go after little

things.

During those chaotic first weeks

in the White House and following bad news about the size of the deficit, Bill

Clinton made one of the most important decisions of his presidency -- to make

deficit reduction the centerpiece of his first budget. Some members of the

staff argued he was turning his back on campaign promises, in particular that

of a middle-class tax cut. And by now Bill Clinton had already lost so much

political capital that his budget was in deep trouble even though Democrats

controlled both houses of Congress.

Begala: My view was that the campaign had been a sacred thing, that it

had been a real compact, because I was there and I saw the connection that

Clinton made with people, and the connection that they made with him. And this

bond, you know, I felt very personally, and I know the president did too. So I

had this, I think now naive notion that you would just then get out your

campaign book and start on page one, and leaf through and enact everything

until you got to page 228. Well, it turns out it doesn't quite work that way,

and people who had been around the block a few times tried to explain it.

Stephanopoulos: I wanted to keep as many of the promises as we could. I

was committed to the putting people first agenda and actually saw my role, in

many ways, as a defender of the promises. So I wanted to do as much of the

investment and keep as much of the tax cut as we could, not to the exclusion of

deficit reduction. But that's more where my heart was and where I thought we

had to protect ourselves politically.

Rubin: Well, the president's view was not that he was abandoning

anything. The president's view was that the circumstances were substantially

worse than he or any of us thought they were. And that even though it was a

very tough path to take, politically, that if he didn't do the tough thing,

politically, which is deal with the deficit, then the thing that he was elected

to do, which is get the economy back on track, wouldn't happen. And the only

way he could get the other things he wanted to do done would be to get the

economy back on track.

Panetta: The president is someone who really loves to get the best

information from the best minds that he can get a hold of. I mean, I have

never seen him intimidated by an in-depth discussion about issues. He loves

that. And I think he kind of relished the fact that there was this debate that

was going on, and that very strong views were being presented. He never said,

"Cool it. I don't want to hear it." Never said that. He always was intense,

he was interested. He wanted to hear the discussions, because I think in the

president's own mind, he constantly was testing exactly, you know, "How far can

I go? What can I do?"

But he was also smart enough to understand that when he looked at some of the

veterans he said, "These guys have been around a while, and they've seen these

wars." And, you know, he recognized the fact that it wasn't Arkansas, that it

wasn't just a question as a governor of a small state working with that kind of

budget. He recognized the differences, and that's why I think he put a

tremendous amount of trust in his economic team, which ultimately I think made

the difference in terms of the final product.

Rubin: When you think of the enormous amount that was accomplished

during that period, it's really quite remarkable. The president, from a

standing start, put together a government. We put together a budget. The

budget, in effect, represented a broad-based economic strategy that represented

really quite dramatic change from where the country had been. And the

president launched that economic strategy to the nation with his speech to the

Congress in February....

Some of the political advisors wanted to see that tax increase using much

different rhetoric. I mean, basically, Paul Begala, you know, wanted to sell

that tax increase as we're "soaking the rich."

Rubin: Yeah. There was debate on the very day that the speech was

delivered. The morning of that day, there was a draft running around, and I

remember going to see Hillary, and saying, "You know, Hillary, I think the

president's got the substantive message exactly right, but I do think there's a

little question here of tone, and I think the president has to decide exactly

what tone he wants to have."

And I remember, Hillary and I went down to speak to Paul, who was sort of the

"holder of the pen," and we went over sections of this with him. And

basically, Hillary said, "Let's make sure that we don't have a divisive tone to

what we're doing." And I think she made an enormous contribution to avoiding

what I think could have been a counterproductive tone.

In April '93, the stimulus package is up, and Republicans are filibustering

it. You go into a meeting and the president is told what's going on, and he

gets really angry. Can you describe that scene to us?

Reich: The president was told that the stimulus package was just not

going to be passed. There was too much opposition. And he was upset. This

was the first big blow to his presidency. I think he was upset, not so much

because the stimulus package itself was not going to go through. There had

been a lot of debate inside the administration as to whether it was a good

idea, whether it would really help jump start the economy anyway. I think he

was upset that as president, given that the Congress was Democrat, he didn't

have enough power, enough authority to get what he wanted done. Already

opposition was forming. Already his ability to change the direction of the

country was being challenged, even in his own party.

Later that summer, in August, the deficit reduction bill finally passes the

Senate, but it is a harrowing day. What do you remember about that?

Rubin: Yes, it was a harrowing day. In the House, as you remember, it

passed by one vote. And I remember being in the Oval Office the night of the

vote, and a little television screen they had there, which showed the floor of

the House, showed the count as it was building. And we were all sitting -- it

was actually in the little back office off the Oval Office -- watching that

vote, and it was, to use your term, harrowing. But, ultimately, it passed by

one vote and I think there was a sense of very great unease as we watched it.

And then of course in the Senate it was a tie and then the vice president cast

the tie-breaking vote.

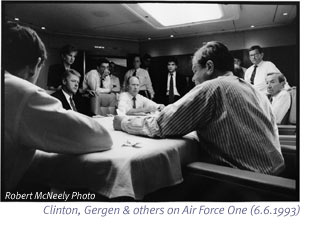

In a controversial move and as part

of an effort to reverse his faltering image, Bill Clinton brought into the

White House David Gergen, advisor to three Republican presidents. For several

months, it looked like the presidency was on track. Nominations were getting

through, the budget was passed (by a single vote), and relations began

improving with the press.

Gergen: It was a bolt out of the blue for me when the calls started

coming. I was working for U.S. News and World Report and writing

editorials urging the administration to pull itself together. I had great

hopes that Bill Clinton would launch a new bipartisan progressive era of

reform. I thought that was really important for the country.

I had been writing pieces about "Do this," and "Do that, please." And finally

Mack McLarty called me and said, "We don't know each other but would you come

over and have lunch with me and talk about some of the things that you've been

writing about? I would like to explore some of these issues with you." So, I

went over to the White House mess and I'm sure Mike had this wired but about

three-quarters of the way through the lunch Bill Clinton came into the mess to

say hello, and we talked for a while. I'd known the president for a long time.

And we talked for a while about what he was up to. And then the lunch ended

and Mack McLarty said to me, "Look, we're really looking for someone with

experience, for a graybeard to come in now. Do you have any recommendations?

Could you think about it?" I said, "Sure, I'll think about it."

And then three or four days later Mack called back and said, "The president and

I have been talking about this and we'd really like to ask you to consider

filling this job that we have." That set off a whirlwind of activity over the

next 72 hours or so in which I talked to the president. He made a very strong

pitch to me by telephone. I met with him personally. I met with the First

Lady personally. I had extensive conversations with the vice president as well

as Mack McLarty....

And then three or four days later Mack called back and said, "The president and

I have been talking about this and we'd really like to ask you to consider

filling this job that we have." That set off a whirlwind of activity over the

next 72 hours or so in which I talked to the president. He made a very strong

pitch to me by telephone. I met with him personally. I met with the First

Lady personally. I had extensive conversations with the vice president as well

as Mack McLarty....

So, when I got there one of the things -- I had this discussion with Mrs.

Clinton as part of my going in. "Look, if I'm going to come in, I've got to

understand how you feel about going to the center, and how you feel about

working with Republicans. I can't come in here as someone who has worked in

three Republican administrations and have you anti-Republican. I can't, I'll

never get anything done. I can't be helpful. And I've got to talk to you

about the press. You know, if there's really going to be a war with the press,

I can't be helpful to you." And she said, "We want to end this war. This is

not where we want to be." And I said, "How about opening the door?" And she

said, "I can't believe it hasn't been done already." And she opened it. She

got it open right away.

What did you tell [the president]? Do you remember?

Gergen: Well, I told him that he was terribly out of position and that

he had lurched to the left when he came in and it sent signals to people like

me, who thought he was going to be a centrist Democrat, that he had lost his

moorings. I also had a private conversation with the first lady saying, "It's

widely perceived on the outside that you're the one who's pulled him left and

that he can't govern here." And then she made a pitch to me about well, that

she was misunderstood, that, in fact, I should remember that she had been a

Goldwater girl in her youth and that she was very much for traditional social

values and she thought he ought to be back to the center. But they also felt

that they didn't understand Washington very well. They didn't understand the

press corps. They didn't understand the dynamics of the press corps. They

were having a hard time figuring out Capitol Hill.

Stephanopoulos: I didn't know what was going on. I knew something was

happening, but I didn't really know. And I went home, it was a Friday night, I

think. It was Memorial Day Weekend. And finally at about 1:30 in the morning

the phone rings. And he says, "George, I think we got to make this

announcement tomorrow morning. I think it's the best thing. I need you by my

side." Perfect thing to say. I mean, I was going to get publicly humiliated.

Moved out of this job. But in three sentences, even though it was late in the

game, he says, "I need you by my side." So that's exactly the reassurance I

needed to hear to go through with the job change. Now, I had -- and fight to

be by his side. But he said exactly the right thing.

... The negative reaction wasn't really personal, like I had known David and

thought he was pretty well-respected. But it was -- we're bringing in Ronald

Reagan's communications director to clean up. What's happening? It felt like

a betrayal of the things that we had fought for.

Myers: Well, the kids who got blamed for a lot of things that went wrong

in the early months of the campaign. The kids weren't responsible for gays in

the military and the kids weren't responsible for the attorney general and, you

know, the kids weren't responsible for the stimulus package failing. You know,

so why was it that the kids were always being blamed?

Gergen: What we tried to do more than anything else in my judgment was

to create an environment for him in which he could make his own recovery. To

tighten the place up, to get the organization tightened up, and to give him the

opportunity to find himself again.

Panetta: Sometimes in preparing him for press conferences, because we

knew there would be questions from the press that would anger him, and the name

of the game is, "Mr. President, don't make news" and so you've got to be

careful how you handle these questions. So we would go through and ask these

questions and his first reaction was to say, "Oh, is that so?" I mean, then he

would really go at it. And the vice president, to his credit, would often say

to the president, "Oh, that's great. Do it just like that, because that's sure

to make the evening news." And the president would kind of look at him, smile,

and then he'd get it together.

Gergen: They had a series of dinners that summer with the press and for

a while there was a truce. It lasted maybe until almost the end of the year of

1993, the first year.

Begala: By July '93, he was not the "gays in the military" president.

He had a singular mission -- and a vote is coming in August, and here it is the

beginning of July, and we don't have our ducks in a row. We didn't have a good

message defined. I don't think we had the right Hill strategy. I don't think

we had anything set in place properly, and he enunciated that very clearly to

us. So we went to work. McLarty decided that we were going to have a special

team organized in a boiler room that Roger Altman would lead, senior guy from

the Treasury Department, one of the smartest people I know both politically and

economically. And then I was the sort of the Democratic Party guy there, and

Gene Sperling and a whole bunch of other people all took time off from

everything else and worked full time to pass that plan. And it worked.

Sometimes you need that. Sometimes leadership requires, you know, knocking

heads together as well as putting heads together.

Panetta: On the Senate side, the most interesting problem we had was

going right to the last vote. Senator Kerrey kept saying-- this is Bob Kerrey

from Nebraska -- that he knew that it was important to get this done, but he

just wasn't sure. He had some concerns about some of the pieces. So we said,

"What are your concerns? We'll deal with those. We'll talk it through."

We're getting close to the vote. We're trying to locate Kerrey. And somebody

tells us that he's in a movie theater in downtown Washington someplace. And

we're all going nuts, saying, "What the hell is he doing going to the show when

we got this big vote coming up tomorrow?" And so we even went as far as to try

to find out, well, what theater is he in? Where is he at? Can we try to get

him?

We had no idea how he was going to vote until the very last moment when his

name was called. We had no idea. And for people that are careful vote

counters, that scares the hell out of you because you have no idea whether

ultimately you are going to win or lose. You're rolling the dice at that

point. And we were rolling the dice with Kerrey.

Reich: Right up to the last minute we didn't know that we had the votes.

There was a lot of arm-twisting, a lot of holding hands, a lot of reassuring.

Some people, some members of Congress, some Democrats who voted for it,

subsequently were punished by the electorate. They did not get back in. They

were worried, justifiably, about their jobs. And right up until the last

moment, in the White House, there was a sense of drama, and foreboding, and

hope. And we watched the tally come in, and we saw that we had enough votes.

Al Gore went up, broke the tie, and there was then jubilation, jubilation. We

had won. This was a big one. This was a hard one we had won.

What was the president's reaction? Do you remember?

Reich: The president was deeply relieved. Had he lost, he would not

just have lost the budget battle, he would have lost enormous political face.

The message would have been, "This guy cannot deliver." And if a president

puts so much behind something and cannot get it done, the president, by

definition, becomes weak.

The intertwining of the Clinton

presidency and scandals started almost immediately. In May of 1993 there were

accusations over the firings in the White House travel office. In July, Deputy

White House Counsel Vince Foster committed suicide and questions began over how

legal material was handled in his office. And then came the allegations that

Governor Clinton had used Arkansas State troopers to procure sexual favors

including those of a woman named "Paula."

Stephanopoulos: We picked a lot of the wrong battles early on. Rather

than simply focus on what we said in the campaign, on the problems of real

people and the fixing those problems, we had this whole separate agenda of

changing the culture of Washington and doing things in a new way.

What fits into that? Having the first lady run the health care project. You

know, we're going to do that in a new way. Showing the press who is boss.

Admirably having a cabinet that looks different from cabinets in the past.

Taking on the lobbyists. A lot of this, there are some good ideas in there,

but much of the time taking on the culture got in the way of advancing our

agenda.

|  |

|  |

Paula Jones and her attorneys hold a press

conference charging Governor Clinton with sexual harrassment.After

initially resisting providing details about her encounters with Clinton,

Jones describes one incident in a hotel room.

(2/11/94)

(46 seconds) |  |  |

|

|

|

Did the travel office story come out of that hubris?

Stephanopoulos: Yeah. We're going to do it our way. We're going to

bring in our own people. These guys have been coddling the press and coddling

our enemies for an awfully long time. They're too closely tied to the

Republicans. Looking back, who cares? What a wasted six months.

Myers: This one we could see coming a little bit but -- we

underestimated the power of the relationships between the former employees of

the travel office and the people who they had served for, anywhere from 10 to

30 years, some of these people. And-- the press rose up in defense of seven

people who they thought were poorly treated. And they were poorly treated.

I think history will show that there was some evidence of -- I don't want to

say malfeasance, because people have been acquitted in the court -- but there

was some unkosher things going on. And, yet, it couldn't have been more poorly

handled if we had scripted it. I mean it was just poorly, poorly handled from

the beginning.

And, you know, George was out of town briefly and so I ended up having to do

the briefing on that first -- and, try to explain this decision which I knew

from my brief experience with the issue was going to be inexplicable. And I

think I got over 100 questions on the same topic.... It's not a briefing, it's

a beating, you know...

'93, when the travel office erupts, perhaps the most problematic thing is

the involvement of the FBI because it brings back, in the Washington press

corps at least, these images of Nixon and the FBI.

Stephanopoulos: At no time in the White House was I more victimized by

being thirteen in 1974. I mean, I know no one will believe it, but what I was

doing that day, I thought, was trying to make sure we were saying the same

thing as the FBI. And it was a fact that the FBI was investigating whatever

happened in the travel office, and I said so. And I was completely blind,

deaf, to the implication that this would make us sound like Nixon. I had no

idea, at one level, what I was saying, even though it was true.

...The president is doing this Larry King Live. And over the course of

the hour the information is confirmed. And it's clear that Vince Foster did

kill himself. We're starting to get the information out. And now we had this

very particular small problem we had to deal with. We knew that Larry King

would ask the president to stay on for another hour. The president still

didn't know that Vince Foster had killed himself. And we were scared to death

that the story would break on the AP wire and Larry King would be asking him

about it. And it would be the first he heard.

So, as a matter of fact, at the end of the hour Larry says, you know, "Do you

want to come back for another hour right now?" And Clinton says yes. And Mack

is standing behind him saying, "No, no, no." And he's looking at Mack and his

eyes widen a little bit. He doesn't really know what it's about. And he's

kind of getting a little annoyed. But then, they stop. And at the break Mack

pulls Clinton aside and tells him.

And I remember watching from across the hall and all I could see was almost an

imperceptible buckling, slumping by Clinton. But he nodded his head, and we

didn't go back for the next hour. And then Clinton, Mack, and I rode up to the

second floor of the residence, the kitchen, and I said, "We're going to have to

put out a statement." And he just said, "You know what to say." And it wasn't

mean or anything like that. It was just he was completely in another place.

And he wanted to go be with Vince's family. And that's what he ended up doing

that evening.

Myers: And so, all of a sudden within a couple of hours we're all of a

sudden dealing with some kind of an investigation of a very sensitive event at

a very high level. And I think it was at that point that I started to realize

that my God, there's going to be all kinds of conspiracy theorists out there.

And I remember saying to Mark and to George, "I have a really bad feeling about

this. I mean it's bad enough that Vince has died but this isn't going to be

treated like a human tragedy, this is the beginning of something that is going

to go on for a long time."

And it did. And the next day, you know, the press asked me, you know, well,

"Why, why, why?" And I said, "It's unknowable." Even though I could see what

was happening, I couldn't stop myself from responding like a human being. You

know, it's unknowable. Why does anybody take their life? How can -- you can

never satisfactorily answer that question. And, of course, that just opened

the door ..."What is it you're trying to hide? Why can't you answer that

question?" It was no longer about the mystery of a human tragedy, it was about

what is the White House trying to cover up. ...

... We knew the story was in the works. Both the American Spectator and

the L.A. Times were working on the story that then-Governor Clinton had

used Arkansas state troopers to procure women. This was a Sunday, and about 5

o'clock that afternoon I got a call from Dave Gergen saying they are faxing it

around or something. We've got a copy of the story.

And once again, your best social plans are foiled by some crisis at the White

House. And, so, that night, we went straight to the White House and started

going over the story and tried to piece together what was it, what do we know

about the accusations made in it? You know, what were we going to say? And I

just remember being there until late that night and again trying to find the

factual inaccuracies in the story and trying to find out who are these

people?...

What was the strategy there to deflect that story?

Myers: It was to once again find the factual errors and to tell the

subsequent story about some of the individuals, some of the state troopers who

had some pretty shady histories. Some of them had been involved in another

scandal subsequent to their service to Clinton while he was governor. And so

we tried to just -- who are these people, what are their motives, what are the

factual inaccuracies in the story, where can we shoot it down.

Stephanopoulos: It was the Spectator and it was stuff that

happened in Arkansas. We had been through that before. And basically, we had

learned that, just these sex stories -- I thought we had learned -- just

weren't going to make that much of a difference. Now, what enraged me, drove

me crazy was this sense that Clinton called like one or two of the troopers

after the story came out. And for me that was pure deja vu, calling Gennifer,

like don't try to fix it yourself. Just let it go. And all of the troubles

always come when you get into this maneuvering of trying to work your way

through it. And, especially calling these people from the Oval Office, just

nuts.

Gergen: And [Hillary] in that kind of environment, her first response is

to rally the troops and get people out defending the president. I think that's

one of the great contributions she's made to him over time. She's the one who

steadies things up. She deploys people, gets them out there.

But I think it was very hurtful to her. I think it was just privately just

very, very difficult for her. Now, let me add this postscript. I believe that

the Troopergate story was a turning point on the health care fight. Let me

explain why. Up until that time that she had been very, very involved in sort

of the effort to put together the health care plan. It had been early

presentations in the fall of 1993. The Troopergate story came along in

December. I think it put him in a substantially one-down situation, with her

psychologically in the dynamics of a marriage.

I can't prove this. My sense has been they are on a see-saw in their

relationship. When that relationship works, they're very good partners. But

when she goes up and he goes down, or he goes up and she goes down, the balance

gets out of whack. On health care, what happened was that that Troopergate

story put that see-saw up so that she went way up and he went way down. And I

never saw him challenge her on health care in the weeks that followed. On the

politics of what was going on, on sort of how to get it presented to the

Congress properly. How to get it through the Congress. I really think that it

sealed her position. It put her firmly in charge of how to get health care

done.

|  |