At the end of 1993, the

Washington Post requested documents relating to the

Whitewater affair. Debate heated up in the White House over whether to call

for the appointment of a special counsel to investigate the matter. Many on

the staff believed it was the only way to calm the controversy, while Mrs.

Clinton and the Clinton legal team believed it would be just the beginning of

prying into the First Couple's private life.

Gergen: Mack set up a coffee that Saturday morning just off the Oval

Office after the president had his radio address to have a chance to talk to

the president. And George Stephanopoulos came to that meeting and he also

agreed on the need for disclosure. I made a very strong argument to the

president why I felt we had to disclose the documents. George was strong. He

was just right there, saying, it's, "You really got to do this." And, Mack

Then he turned to me and said, "Now, you've got to go talk to my wife. You got

to persuade her to do it." I said, "Okay, fine." So, that Monday morning I

started calling for an appointment. I never got an appointment. They kept on

saying, "I'm sorry, she's too busy." Too busy.

Which told you what?

Gergen: It told me she made up her mind, didn't really want to hear the

argument. And it also told me that she had a veto power over this question.

And that, in fact, there were, on some issues, there was a co-presidency.

Stephanopoulos: Gergen kind of took the tack of "You've actually

received quite favorable coverage from the Washington Post. You

received the best first year of coverage of any president I've ever worked

with." And I took a somewhat different tack to kind of get to the same end. I

kind of agreed with the president. "Mr. President, you're right. The

Post has been unfair. All the press has been unfair. They've been out to

get you from the start. All the more reason to give them this right now.

Don't give an excuse. Instead, let's just give them the documents then we'll

move on. And you won't open yourself up to the cover up charge."

I thought we had him convinced. It seemed to me at the time that we had him

convinced. He said he wanted to go think about it. He went back later that

afternoon and we just got the word through Mack that he decided not to. And,

you know, basically the lawyer said it was too risky. Hillary and the lawyer

said it was too risky and they weren't going to do it.

Myers: And I think David Kendall and some other people believed that

once you did that, once you started turning over your personal records of

events that transpired 20 years ago, that had nothing to do with your

stewardship of the country, nothing to do with your role as president or first

lady, nothing to do with the public trust, that you couldn't, you would never

stop. That the requests would come and come and come. Today it's Whitewater,

tomorrow it's tax returns or whatever. And that it would just open a door that

they didn't want to open. And, in some ways, I mean, it's their life. It was

hard for us to argue that they should walk through that door.

Reich: I think that they were very hurt by that Whitewater

investigation. The first lady was bewildered by it. She had already taken a

great deal of heat during the campaign of 1992 for who she was, for how she

acted. And she felt hurt by that. The Whitewater investigation, she felt, was

unjustified. There was nothing wrong. They did nothing. It seemed to be some

sort of a political vendetta. And in the midst of everything else that Bill

Clinton wanted to do and the first lady wanted to do, it seemed just a huge

burden.

Gergen: I honestly believe had we turned over the documents to the

Washington Post in late 1993, we would not have had this hunt in the

press for the documents and hunting down the Clintons. We never would have had

an independent counsel appointed in 1994. There would never have been a Ken

Starr. And there might have been a Monica Lewinsky in Bill Clinton's life, but

I don't think we ever would have heard about her.

To me that was one of the most serious turning points in the administration

because I think that refusal to cooperate with the press led directly to the

pressure to get an independent counsel. And then the avalanche that came, the

pressure that came was so much, the White House couldn't resist it.

Stephanopoulos: If I could take back one day, one decision in my time at

the White House, it would be the decision made on December 11, 1993 not to turn

over those papers to the Washington Post. Can't be proved, but I firmly

believe that we turn those over, we would have never had a Whitewater special

counsel. If you never have the Whitewater special counsel, you never have

Monica. You never have the impeachment of the president.

And we have a final conference call. It had been arranged by Harold Ickes. We

were going to have a final mini-debate on the question over the phone for the

president. Bernie Nussbaum was arguing the case against asking for a special

counsel. I was leading the team that said, "We have no choice but to ask for

one." [W]e had this argument over the speakerphone. I argued one side, Bernie

argued the other. Now, it turns out that Bernie's warnings were correct. He

said, "Listen, once you have a special counsel, you can't control it." That

may be, but we had no choice. If we didn't do it ourselves, it was being done

to us. We already had majorities in the

Congress against us. And they could have gotten one appointed without our

consent. And I said this was the only way to show that we were open and to

move on. And the president finally agreed.

Panetta: Congress then enacted the legislation to continue [the office

of the independent counsel]. And I remember going in and saying that the bill

had been passed by the House and the Senate, and that the decision now was with

the president and the White House as to whether or not to sign it. And the

president looked at me and he kind of said, "You think I should sign this?" I

said, "Well, Mr. President," I said, "Clearly there was overwhelming support in

the House and the Senate. If you wind up vetoing this, you're going to be

overridden by both the House and the Senate."

And he said, "I know. I know." He says, "But you know, why do I have this

feeling I'm making a mistake?" or words to that effect. So we always had some

qualms about, establishing that kind of power and what it could possibly mean.

And he always recollected that, you know, during the next few months.

... And [Clinton's] feeling was that essentially a deal had been made to get

rid of Fiske and put Starr in and that that spelled trouble for him. There was

no question, I think, in his mind that a political decision had been made. He

wasn't sure who was involved but there was no question in his mind that this

was not just the court acting out of a sense of justice. He felt this was

basically part of a political effort to go after him.

Carville: Let me tell you what the thinking is because it is very

important that you understand it. August 9th, 1994, when Starr was appointed,

I wrote a letter to Leon Panetta saying I turned everything in. I don't want

any association with anything. This is a disaster. I won't fight him. This

guy is gonna be a political guy. I feel it in my bones. Then everybody calls

me hyperventilating, "Please don't do this. And this person's gonna quit. And

oh no, no no." Stupidly, I went along with it. Course I was proven right.

Stupidly because you decided to keep quiet.

Carville: Because George called me and you know what I mean and said

"Don't do this. Don't speak out against Starr." I stupidly went along with

it. And then I couldn't take it anymore when he was out representing cigarette

companies and giving speeches at Pat Robertson's university and subpoenaing

everything and investigating women and god knows what not and pointing at every

hack Republican he could find. Fifty million dollars into it the whole thing:

Whitewater, Travelgate, Filegate, garbage.

Stephanopoulos: James was crazed. He said from the absolute start "We

have to go for this guy, he's a right-winger, he's a zealot, no good is going

to come of this. We have to make it clear that he's illegitimate from the

start." And he wanted to start a campaign against Starr from the first day he

was appointed.

Panetta: Well there were those of us who were concerned when [Carville]

was doing that, because we thought even though Jim Carville was acting out of

his own concern for Starr, the relationship between the president and Carville

was such that people immediately put their two and two together and figured the

president is clearly behind this. So there was no question that the impression

was that he was getting signals from the president to do this. And, again,

when you're President of the United States, it was my view that the president

has to be above that and that he can't just suddenly grovel and look like he's

engaging in political warfare with somebody who, frankly, carries his fate in

his hands.

|

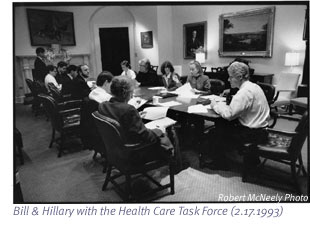

His first week in office, President

Clinton made good on his pledge of "buy one, get one free" when he appointed

his wife to head the new health care task force. While some in the

administration welcomed Mrs. Clinton's input, others feared her wrath. The

first lady was initially praised for her work on health care. But, as details

of the plan came under fire and she became the primary target of the Whitewater

investigation, the health care plan faced defeat. Its failure had a

devastating effect on Mrs. Clinton and on the White House.

Reich: The first lady was the first advisor, the most important advisor.

Al Gore was the second most important advisor. But Hillary Rodham Clinton's

influence was on every domestic policy that was important... She had not been

elected to anything. She had not been directly appointed in terms of a formal

appointment, to anything. And because she is the wife of the president, it's

difficult for people to criticize her, to say, "No, you mustn't do this, that's

wrong," because, after all, you're talking to the wife of the president. And

so there was a subtle intimidation that also went on among the people who were

working on [health care].

Reich: The first lady was the first advisor, the most important advisor.

Al Gore was the second most important advisor. But Hillary Rodham Clinton's

influence was on every domestic policy that was important... She had not been

elected to anything. She had not been directly appointed in terms of a formal

appointment, to anything. And because she is the wife of the president, it's

difficult for people to criticize her, to say, "No, you mustn't do this, that's

wrong," because, after all, you're talking to the wife of the president. And

so there was a subtle intimidation that also went on among the people who were

working on [health care].

Emanuel: You had to have your argument down. And if you weren't

succinct or had thought through -- I mean, there's two sides to this. If you

were, if you were kind of just mealy mouthed, she didn't respect you. And if

you went in forceful but had not thought through, she didn't respect you. And

she respected people even if she disagreed with them. But you better be good

at it and you better know what you're talking about. That's not an unhelpful

attribute in my view.

Myers: She was I think from start to finish, a force. And I

think there was a strong perception that she was somebody that you did not want

to cross. You didn't want to get on the wrong side of Hillary. And some

people were better at it than others. I mean some people were better at it

than I was. I certainly never intentionally did anything to upset her. I

tried not to, but there were times when I did what I thought was right and it

made her mad.

Shalala: Well, for a major principal in the White House, who wasn't on

the government payroll, it was highly unusual. There's no question about that.

Was it a bad political judgment to have her? We wouldn't be having this

discussion if we were successful, and I would argue that it was high risk, high

gain, and the president took that risk. And would I have advised him to do

that? He didn't ask me at the time. I wasn't surprised that he decided to do

that.

Stephanopoulos: There wasn't a lot of discussion beforehand. I got to

say, I looked at it and thought, "You know, this will work." It shows how much

the president cares about an issue. He's putting his wife in charge, the

person that he's closest to in the world. It shows his commitment. It was my

own blind spot too.

Gergen: I mean she's a great policy analyst but he has, as you know, he

has perfect pitch in politics. He can hear, he can sense, he knows, he's

finely tuned, about the political environment. I don't think that health care

bill would ever have looked the way it did had he been fully engaged, had he

been in charge of the process.

Reich: The economic group, of which I was a member, didn't really know

what was going on. The health care task force was meeting in secret, and we

only heard rumors about --

Even though you were the Secretary of Labor.

Reich: Even though I was the Secretary of Labor, it didn't matter. We

were still not in the loop with regard to health care. Finally, we all got

together, Ron Brown and Lloyd Bentsen, Bob Rubin, Laura Tyson and I, and a few

others, and said to the president and the chief of staff, "Look, we have to

know what's happening here. We've got to be able to evaluate this in economic

terms. What we've heard sounds a little bit -- well, a little scary. It may

be right. It may be a good plan, but we want to subject it to some sort of

economic analysis, some sort of evaluation." And at that point we did begin to

get involved.

What was the reaction from the president when he hears his economic team is

getting worried about his wife's pet project?

Reich: The president was not pleased that there was potential discord in

the ranks... given the amount of political capital he had already sunk into

this issue. He had already been making speeches, he had devoted a great deal

of attention to this, he had been involved with the first lady and Ira

Magaziner in discussing the details of this plan. For, at this late stage, the

economic team to nose its way in and start asking hard questions and express

doubts, well, that didn't meet with a great deal of joy on his part.

Shalala: We were taking a huge risk by taking on the whole system. All

of the literature -- I'm a political scientist -- says that if you're gonna

take a giant step, there has to be consensus nationally. That there is a

problem, and consensus about the solution. We read the problem correctly.

Americans were quite unhappy with the health care system. They were worried

about it. We had large numbers of Americans without health insurance. We

assumed that we could develop a solution that, in fact, had consensus, but the

fact was there wasn't consensus on a solution. There wasn't a consensus on an

approach, whether it was single payer. There was a consensus that we ought to

have health care for everybody, but none on how you get there, whether you do

it through a public/private system, whether you do it gradually or over time.

And, in some ways, we misread that, and from the beginning, all of us were

nervous about that, because we had never seen a process like the one that we

were going through. But Mrs. Clinton and I never disagreed about the goal or

about the focus on health care in particular.

Gergen: I don't want to put the blame on her on health care. I don't

think that's fair. I don't think she ever should have been asked to put the

health care thing together. I think Donna Shalala should have been asked to

put that together and I think Mrs. Clinton could have led the crusade to get it

passed. But ultimately this was Bill Clinton's White House. He was the guy

elected president. Ultimately if your wife gets assigned health care that's

his decision. And, so, you have to say, "Mr. President, you did a lot of

really good things as president but turning the health care program over to

Mrs. Clinton, who had never really worked in Washington before and asking her

to do something that massive was like giving her a mission impossible." It

just was more than she should have been asked to do.

Reich: One cannot understate that extraordinary impact that that health

care defeat had, not only on the first lady, on the president, on the White

House overall -- it shook the confidence of everyone.... I think there really

is a lot of pain, a lot of hurt, and all of us felt that we had lost a very,

very important battle.

... There had been a lot of stumbles, but I think the health care

defeat was perhaps the biggest stumble of all.... It was devastating, and it

set the Republicans up for a major victory in November. You see, the 1994

election and that defeat can't be separated really from health care. They are

part and parcel the same process. The Republicans had made it very clear

during the health care debate that they did not want that bill to pass. They

made a very clear and conscious and very specific decision. It was a strategic

decision. There would be no health care bill, there would be no health care

legislation. The president would not get this win.

|

During his first two years in office, the

president fought tough and costly fights -- in particular deficit reduction,

NAFTA, the crime bill, and health care. Republicans used these issues combined

with the scandals surrounding the Clintons to clobber Democrats in the fall of

1994. The effect was catastrophic -- Democrats lost both the House and the

Senate and Newt Gingrich became the president's nemesis. For several days

after the election the president was in a funk, but characteristic of Bill

Clinton, he was also plotting his comeback.

Stephanopoulos: Working, working, working, working. "Who can I call?

What can I do?" He was doing radio calls to California all day. He knew the

election was going south and he wanted to do whatever he could to turn it

around.

Now, of course, one of the problems in the '94 election was that in some ways

the more Clinton did, the more he hurt himself. He was the issue in large

measure. That was the year when all those ads were morphing Democratic

congressmen into Clinton over the course of the ad. Because of the

disorganization in the White House, because of the scandals, he had become the

issue. Now, it's also true that he was being punished for the hard fights he

had taken on, assault weapons ban, by passing the economic plan which included

a tax increase and some Social Security cuts, trying to get health care and

failing. They were using his good fights against him and his bad character

traits against him at the same time. And it was a real combustible mixture.

Reich: But to lose the House and to lose the Senate and to lose so many

state governorships, to lose so many state legislators, for there to be such a

big shift, was an overwhelming defeat. There was no way to interpret it as

anything but a repudiation of the Clinton administration, and that's how we saw

it. It was a dismal day. I went over to the White House just to see how the

president was doing, how other people were doing, and he tried to put the best

face possible on it, but he was devastated. Everybody was devastated.

Stephanopoulos: If you really look back now, the defeat in '94 was, in

large measure, a result of the votes that were made in 1993 -- a tax increase,

a Social Security increase, NAFTA, which depressed our base, and those gun

votes. And the truth was that the hard votes had been taken, but the positive

consequences weren't manifest yet to people. You combine that with all of our

very early stumbles, our image problems, gays in the military, a White House

too young and too chaotic, and the president's own personal stylistic problems

early on. It's a recipe for disaster.

Stephanopoulos: If you really look back now, the defeat in '94 was, in

large measure, a result of the votes that were made in 1993 -- a tax increase,

a Social Security increase, NAFTA, which depressed our base, and those gun

votes. And the truth was that the hard votes had been taken, but the positive

consequences weren't manifest yet to people. You combine that with all of our

very early stumbles, our image problems, gays in the military, a White House

too young and too chaotic, and the president's own personal stylistic problems

early on. It's a recipe for disaster.

Panetta: And that night, when the results started coming in, it was

pretty early in the evening when the handwriting was on the wall. And I guess

it was George Stephanopoulos came in and said, "This is a landslide." And I

kept saying, "No. No. It can't be that bad."

He says, "Yeah." He says, "I think we're -- I think we're going to lose the

Senate and we may lose the House."

And my own thought was "We've lost the Senate before." I never thought we

would lose the House. And then when that happened and we knew we had a

Republican house, Speaker Gingrich and the Senate, we knew we were going to

face some real problems.

Myers: He was furious. He was just furious. And I mean he went into a

real funk and spent a lot of time thinking, blaming other people, feeling sorry

for himself... He did definitely go into a funk there for a couple of weeks.

He was very low, frustrated, dispirited but he never quits. And while I think

a lot of us were seeing his funk and his frustration as anger, thought he had

been poorly served by some of the strategists, he was already plotting his

comeback.

Stephanopoulos: Depression. I had never seen him in more of a funk than

in those three to four weeks immediately following the campaign.

Rubin: But what was most interesting to me was that this was one of

those kinds of events in life that just shake you at your footing, and you sort

of have to rethink your footing and where you are. But then the president led

the way back, because he thought his way through to where he wanted to position

himself, and he got himself back on his feet, figured out where he wanted to go

from there. And actually, if you think about it, the administration did very

well from that point forward.

Reich: The message was -- we've got to change our ways. We've got to

reinvent ourselves. We've got to do something fundamentally different. But we

didn't know what we had to do differently. Some of us felt that the president

had to be more forceful on behalf of working people, and had to come out

fighting. Some people thought he had to move to the right, and there was a big

internal debate about whether you fight or move right.

|  |