|

The transition. You were down there as an observer for U.S. News and

World Report. But you'd been in three other administrations. What did you

sense about the transition and how this newly elected president was putting

together his team?

What I sensed was that they had a fantastic public relations machine going

in Little Rock so that he got only 43 percent of the vote in the election but

by the end of the transition he was up to 59 percent approval. But beneath the

public relations machine, a real mess was building up in my judgment.

They did not seize the transition as a way to govern. It became more of an

extension of the campaign with the public relations side of it than it was the

movement from campaigning to governing. And I think that cost them a lot when

they got to the White House.

Ordinarily, in a transition, what you want to do is to make sure you get

your team ready, to make sure you get your program ready and to make sure you

get your president ready so he's physically ready, rested and ready to go. And

they did pick a good economic team but on the rest of it he, he put his White

House team together at the last minute. People didn't know where they were

going to be sitting until the last minute, didn't know what their jobs were

going to be.

He didn't have his program together by the time he hit Washington, and when

he came to Washington he was exhausted. You know, kept running during the

transition. He kept out there, physically out there, and instead of getting a

rest,by the time he got to Washington, he was a very tired guy. And I think

that left him in Washington--a man who is as talented as he is, his judgment

was not as good as it was when he was governor.

The first two problems that hit him as president were the Attorney

General nomination thing, and gays in the military. To what extent were both

of those things a result of sloppiness in the transition?

I think that the continuing bumbles on the attorney general decision came

out of two things. One, they were being so fastidious about filling the slot

with a woman that they weren't looking for merit, they were looking for a

woman. And as a result of that they found one person they hadn't checked out

enough, and they went through another, and that sort of thing and wound up with

a third candidate. But it took a long, long time to get that in place.

You have to give him credit for diversity. This is the first president in

history who appointed the Cabinet where white males were in a minority. That's

something different, that's new. And he got the diversity he was looking for

but in the obsession with diversity, he, it was so slow that he wasn't ready to

govern.

And it wasn't just the attorney general slot that was so slow in being

filled. The fact was because they took so much time on the attorney general,

they never got the sub-Cabinet done. So, what you had at the Justice

Department was a shell of a department. You know, Web Hubbell was basically

running the Justice Department for a good long time there at the beginning.

And whatever you may think about Web Hubbell you needed more people there in

place to really run a department. And that was true not only at Justice, it

was true in a lot of different parts.

I think that the problem goes back to the fact that it's a bigger leap from

a place like Little Rock to Washington than people imagine. Bill Clinton, one

of the most talented political figures of his generation, certainly, found it

much tougher. It was much, much tougher than he anticipated coming here and he

did not surround himself with a lot of Washington veterans early on.

But he did that on purpose. I mean there was, as you recall, a

tremendous resentment among the campaign from anyone who had been associated

with the graybeards of Washington. Those sorts of people were specifically not

welcome.

They were not welcome. And I think that was a terrible mistake. If I can

only suggest two contrasts. One, when Bill Clinton put together his campaign

he reached out far and wide for people of all different backgrounds regardless

of what their loyalties had been before. And as a result he got a crackerjack

team. He had a really first-rate campaign team. They were not welcome. And I think that was a terrible mistake. If I can

only suggest two contrasts. One, when Bill Clinton put together his campaign

he reached out far and wide for people of all different backgrounds regardless

of what their loyalties had been before. And as a result he got a crackerjack

team. He had a really first-rate campaign team.

But when it came to governing, he did not use that same sort of net to

bring in the best. If someone had worked for the Carter White House, it was

almost by definition no place for him in the Clinton White House. Let me give

you an example.

Mack McLarty, who is a wonderful gentleman, to come as Chief of Staff,

wanted to have Stu Eizenstat as his deputy. Eizenstat was ready to

come. He had been Jimmy Carter's chief domestic advisor and is just a

first-rate public servant. Eizenstat was vetoed by the high command of the

Clinton team because he worked for Carter.

As a result, McLarty never had the man who would have been so valuable to

him, right from the beginning, who really knew how to run a White House. And,

as it's turned out, of course, Eizenstat went on to work over in the foreign

policy side and, of course, he has distinguished himself at the State

Department, the Treasury Department, because he is so good.

But it was the nixing of people like that. They nixed Eizenstat, they

nixed Mike McCurry from coming into the White House. Mike McCurry could have

come in and he and Dee Dee would have been a terrific team early on. But they

nixed McCurry because he had worked for Bob Kerrey and he'd been for other

people.

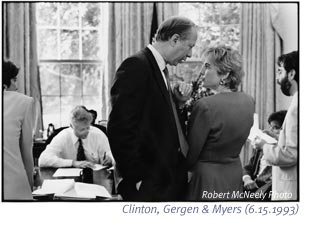

Jump ahead to May of 1993, how are you approached to come to the White

House and what is the argument, what is the pitch that you are

given?

It was a bolt out of the blue for me when the calls started coming. I was

working for U.S. News and World Report and writing editorials urging the

administration to pull itself together. I had great hopes that Bill Clinton

would launch a new bipartisan progressive era of reform. I thought that was

really important for the country.

I had been writing pieces about, do this, and do that, please. And finally

Mack McLarty called me and said, "We don't know each other but would you come

over and have lunch with me and talk about some of the things that you've been

writing about? I would like to explore some of these issues with you." So, I

went over to the White House mess and I'm sure Mike had this wired but about

three-quarters of the way through the lunch Bill Clinton came into the mess to

say hello, and we talked for a while. I'd known the president for a long

time.

I had been writing pieces about, do this, and do that, please. And finally

Mack McLarty called me and said, "We don't know each other but would you come

over and have lunch with me and talk about some of the things that you've been

writing about? I would like to explore some of these issues with you." So, I

went over to the White House mess and I'm sure Mike had this wired but about

three-quarters of the way through the lunch Bill Clinton came into the mess to

say hello, and we talked for a while. I'd known the president for a long

time.

And we talked for a while about what he was up to. And then the lunch

ended and, and Mack McLarty said to me, "Look, we're really looking for

someone with experience,for a graybeard to come in now. Do you have any

recommendations? Could you think about it?" I said, "Sure, I'll think about

it."

So, he called me that Sunday at home and said, "Have you thought about it?"

And I said yes---one of the people I recommended was Stu Eizenstat. I

recommended all Democrats. But Stu Eizenstat I thought would be a terrific

person to come in. I didn't know the history from before that. And then three

or four days later Mack called back and said, "The president and I have been

talking about this and we'd really like to ask you to consider filling this job

that we have."

That set off a whirlwind of activity over the next 72 hours or so in which

I talked to the president. He made a very strong pitch to me by telephone. I

met with him personally. I met with the first lady personally. I had

extensive conversations with the vice president as well as Mack

McLarty.

Did you tell the president what you thought was going wrong with his

administration at that point?

Well, I didn't need to tell him what was going wrong because he told me.

He was very reflective. He thought that the administration was way out of

position politically. That he had intended to come as a New Democrat and he

was perceived as being way off to the left and he had to get back to the center

and he had to get back to working with Republicans and he thought I could be a

potential bridge to help get back to the center where he wanted to

govern.

What did you tell him?

Well, I told him that he was terribly out of position and that he

had lurched to the left when he came in and it sent signals to people like me,

who thought he was going to be a centrist Democrat, that he had lost his

moorings. I also had a private conversation with the first lady saying, it's

widely perceived on the outside that you're the one who's pulled him left and

that he can't govern here.

And then she made a pitch to me about well, that she was misunderstood,

that, in fact, I should remember that she had been a Goldwater girl in her

youth and that she was very much for traditional social values and she thought

he ought to be back to the center. And they also felt that they didn't

understand Washington very well. They didn't understand the dynamics of the

press corps. They were having a hard time figuring out Capitol Hill.

They were asking the right questions. It was just the fact that it was

several months into the Administration and they had paid a fearful price by

that time. I mean he was in a pretty deep hole several months in. I believe

Sam Donaldson had declared him dead politically just a few weeks after he took

office.

And there were widespread feelings in Washington that he was in over his

head. That they had slipped on one banana peel after another. So, the call to

me was emblematic of someone in Washington who understood the press, who knew

something about bipartisan politics, who knew something about the White House

and perhaps could help them right themselves to come out of the ditch.

When you get to the White House, what are your first early impressions

of how it's working?

The thing that struck me the most forcefully when I first got to the White

House was the fact that Bill Clinton, a man I had known for 10 years,

self-confident, optimistic, always a man who, if he made a mistake on Tuesday

and got knocked down Wednesday, he'd bounce right back up and be sunny. And

here was a fellow who had lost his way and most importantly he had lost his

self-confidence. He didn't believe in himself in the same way he did, the man

I'd known. He was a very, very different person.

And what I had learned from other presidents, particularly with Reagan, was

that the best thing a staff can do is don't try to reinvent the person.

Instead try to help the person bring the best out of themselves. We said,

"Let Reagan be Reagan."

And my view was let Clinton be Clinton. He's got it within him. He's got

the resources within him but he'd lost his confidence. And so what we tried to

do more than anything else in my judgment was to create an environment for him

in which he could make his own recovery. To tighten the place up, to get the

organization tightened up, and to give him the opportunity to find himself

again.

You say, "get the organization tightened up." You hear and read these

accounts of endless meetings where the president is engaged by practically

anybody who walked past. That policy discussions go on until 2 - 3 o'clock in

the morning. That there's this sense of a free flowing dorm room almost. I

mean, how would you put it?

Well, early when I got there somebody told me, I think the vice president

had this view--the comparison was have you ever watched 10-year olds play

soccer? And if you have, what you notice is they never hold position. They're

always clustered around the ball. There are tons of them clustered around the

ball. This is what was happening in the White House unfortunately. Bill

Clinton was the ball and wherever he was, there were tons of people clustered

around.

And it was for me, who had come from Republican administrations, which are

very buttoned up, very hierarchical, very orderly, it was stunning. I mean I

realize the Democrats are different in some ways. They like a little chaos.

They think it's more creative. And, hey--who's to say they're wrong.

And it was for me, who had come from Republican administrations, which are

very buttoned up, very hierarchical, very orderly, it was stunning. I mean I

realize the Democrats are different in some ways. They like a little chaos.

They think it's more creative. And, hey--who's to say they're wrong.

But in this case, it was totally chaotic. And I think that from the

president's point of view it was unsettling. He had no time for reflection.

He had no time to rest. And I think it was almost like he was in this

never-never land, he was in the fun house. He didn't know how to find his way

out of it. And it took a while to let that sort of settle this down, slow this

down, let him find himself and he'll be fine. And he did. I mean he worked

his way out of the hole. But it took a while.

I will just give you an example. I am used to a White House where normally

the president is in the Oval Office and there is a fairly orderly discussion,

it may be three people, may be four people, but not very many and everybody

sort of waits for somebody else to speak.

And more than once the situation I saw was Bill Clinton was going to go out

to the Rose Garden to do an event and the press would be out there. And

suddenly, ten minutes before the event, people would pour into the office, to

give him advice. And everybody would be milling around as the fellow was

trying to get himself ready to go out there. And somebody would be whispering

in his ear, somebody would stick a piece of paper in his pocket, somebody would

say, "You got to say this," and somebody else would say, "No, no, no, you got

to say that." It bordered on chaos.

And I think that he realized that he needed to stop that and he did. And

over time he became a lot more effective as president over time. I think that

should be emphasized, but in the beginning I think that he suffered a lot. This

cannot be overemphasized enough. He suffered a lot from not bringing in some

people from the Carter administration and from the previous Democratic

administrations who knew Washington, who knew the White House and who knew

what it took to govern.

He would have been a lot better had he integrated the campaign team, very

talented people, George Stephanopoulos, Dee Dee Myers, Paul Begala, James

Carville, Mandy Grunwald, Stan Greenberg. They are all very, very talented.

And he needed those people. They were vital to him. But he also needed a few

of the graybeards. He needed the Bob Strauss types or he needed the Stu

Eizenstats who could come in and say "Okay, that's all great, that's the energy

of the campaign, but now to translate that into governing, you've got to put

together an integrated team."

Once again, I have to go back--I think the best transition in modern times

has been the Reagan transition. Jack Kennedy also had a fantastically good

transition. One of the things that distinguished Reagan was that he brought

his California team with him but then he reached out and got Jim Baker straight

out of the Washington establishment, in effect, to be his chief of staff. And

he blended the Washington folks with the California folks and by that he got a

very strong team.

And what Clinton tried was bringing his campaign team in, but didn't reach

out and get any of these veterans.

You mentioned that you saw the president lacking the confidence that you

had seen him demonstrate before. One of the things that you and Mandy Grunwald

did was look at videos from Clinton as candidate to Clinton as president. What

did you notice in the comparison of those videos and then what did you do about

it?

Yeah. Well, the credit for the videos belongs to Mandy and I didn't have

anything to do with the production of them. I did see them. And the videos

showed that the president when he was campaigning spoke with a vision about

what kind of country we could be. He was thematic and he was sort of

lofty. And he talked about the problems facing us and the solutions facing us

as a people.

When he became president the conversation on the news was all about

process, it was about this committee or that committee and "We've got a group

working on this." It lost that sense of vision, that sense of what drew

people to him. And I remember very well a meeting with him in which he

complained, "I'm becoming the mechanic in chief and I don't want to be there.

That's not who I got elected to be."

You know, Ross Perot had that wonderful metaphor about looking under the

hood of the car and figuring out what's wrong. The president is not supposed

to be the guy under the hood of the car. The president is supposed to be the

person in the driver's seat figuring out what the road map looks like and where

you're going.

Was part of it Clinton's fault? He was known to be hands-on, he wanted

to be in every decision. In fact, people have told us that he couldn't stand

not being in decisions and discussions.

Bill Clinton, because his mind is so quick and because he's so

comprehensive in what he thinks about, he did want to be in every decision. I think he realized after a while he was getting lost in the trees and

couldn't see the forest and he needed to sort of pull back from that he could

not only think in, in a different way but he could present to the country a

different sense of what his presidency was all about.

He'd never got quite into the detailed hands-on relationship that say,

Jimmy Carter did. Remember Carter got into the point where he was actually

approving who would play on the White House tennis court and he would look at

the schedule. Clinton never got that far. But what instead was happening was

that on policy issues, he would dive in and get deeper and deeper and deeper

and he could get mired down in the details, and it was really hard. There

is such a thing in government as paralysis by analysis.

By the time you got to the White House, relations with the press in this

town were already pretty bad. A couple of things had happened. For one thing,

the hallway had been blocked off to George's office, but generally there was a

lot of enmity there. Where did that come from?

The press had fallen in love with Bill Clinton for a portion of the

campaign. And then they started falling out of love. That frequently happens

with candidates.

But the Clintons had gone through a just grueling experience with the press

during the campaign, especially in New Hampshire and they came out of that very

banged up, psychologically wounded by it and angry. There was a lot of

hostility deep down about what these people did to us in the campaign. They

didn't treat us fairly.

Mrs. Clinton felt that very strongly. So that when they got to the White

House, there was a sense, "We can't trust these people. Let's put them

somewhere else. Let's take them out of the White House." So, there'd be early

on the discussions were, before I got there, "Let's put them over in the Old

Executive Building across the street, get them out of the White House." Now,

they realized after they looked at it that that was not a good solution. But

the compromise was to close the door between the press and the offices of

George Stephanopoulos and Dee Dee Myers.

Now, it's always been my understanding that both George and Dee Dee wanted

that door open. But it was ordered closed over their objections. And may seem

to the outside world so what? But it's actually quite important to the free

flow of information in the White House.

So when I got there, I had this discussion with Mrs. Clinton as part of my

going in--"Look, if I'm going to come in, I've got to understand how you feel

about going to the center, and how you feel about working with Republicans. I

can't come in here as someone who has worked in three Republican

administrations and have you anti-Republican. I'll never get anything done. I

can't be helpful. And, I've got to talk to you about the press. You know, if

there's really going to be a war with the press, I can't be helpful to you."

And she said, "We want to end this war. This is not where we want to be." And

I said, "How about opening the door?" And she said, "I can't believe it hasn't

been done already." And she opened it. She got it open right away.

And I was really surprised. I didn't know what to think of that. I never

have known what to think of that. But, they then went--and they'd been

planning this long before I got there---they had a series of dinners that

summer with the press and for a while there was a truce. It lasted maybe until

almost the end of the year of 1993, the first year.

You were involved in an episode which sort of illustrated the "us versus

them attitude," when The Wall Street Journal preparing a sort of series

of what were relatively hostile editorials asking questions like, "Who was Vince

Foster?" The Journal calls and they want a picture. What

happens?

I thought my role early on for better or for worse, was to see if we

couldn't sort of build a truce with the press and get to a more normal

relationship with the press, with the Congress, with the leaders of Washington.

And so when The Wall Street Journal was looking for pictures, knowing

they were going to do the drawings of these people and knowing that they were

probably going to be critical--I mean The Wall Street Journal

didn't pull any punches about how critical it was of the Clinton

administration--my view was, "Look guys, they don't like you. They're never

going to like you. But you're crazy if you don't sort of act like this is a

professional operation. Of course we'll send you the picture. This is public

information. You are public figures."

And Vince Foster and Bill Kennedy did send their pictures up there and

The Journal did nail them. But it was a lot better. And The

Journal called back and said, you know, at least you guys are talking to

us.

Now, this is the reason I want to go back to the Washington experience.

This is not rocket science. Relationships with the press are a matter of pure

professionalism. They are professionals. They have a job to do. It's not

your job. It's a different job. You've got a job to do and you've got to have

a professional to professional trust, a relationship of trust. Even though

they're going to nail you sometimes.

And my experience from Watergate on has been you're better off acting like

this is an important part of the process and let's open up to it, then you are

to go out hostilely and say we're not going to cooperate with you guys on

anything.

To me there was a significant turning point in the relationship with the

press that led to the Whitewater Independent Counsel. And George

Stephanopoulos, and I were both involved with this. There came a time when

The Washington Post was seeking Whitewater documents and this was in the

late Fall, early Winter, 1993. And they sent a letter over asking for the

documents and, and the letter sat there for two weeks without being, without

getting an answer. And then Bob Kaiser of The Post called me and said,

"You're fairly new over there, still--you know this is serious. We feel like

we're getting the run-around."

To make a long story short, Bruce Lindsay, Mark Gearan and I went to The

Post. Mark and I--Mark was then communications director--recommended to

the Clintons that they turn over the documents. We had a climatic meeting with

the president who agreed to turn over all the documents but then told me, you

got to get Mrs. Clinton to agree to this before we do it.

And I couldn't get it on her calendar. They wouldn't let me in to see her.

I got into a stall situation. And eventually a letter went back to The Post

saying, no deal. In fact, it was a lot tougher than that.

What did that tell you about the relationship when it would come to

something like that where Mrs. Clinton obviously was driving the ball

here?

Well, there are a couple of things. Let me finish upon the press story and

then I'll come back on the the Clinton story. The press side of this was--this

was a turning point for The Washington Post. They made a very serious

re-request for documents. And we, in effect, put a stick in their eye. And it

was just as sure as night follows day they then put a large team of

investigators on the situation and they really went after them.

And it was clear it was coming, and the Clintons were told it was coming.

But Len Downey of The Post called me and said, "This is not personal,

this is just business. But I want to tell you something, you folks have made a

horrible mistake and we have no choice now but to look at this very seriously."

And once that started, that's the flagship newspaper of politics in Washington,

everybody else got into this thing. Newsweek was there, everybody else

was there. And it really put the pressure on where are the documents, and

eventually as you recall, the Clintons decided to voluntarily turn the

documents over to the Justice Department and they, themselves, called for an

Independent Counsel. And I think it was very symbolically important that on

January 20, 1994, exactly one year after he'd taken the oath of office, the

Independent Counsel was appointed. And Mr. Fiske came in and said, "There is no

limit to what I'm looking at." And that's exactly where he was going.

I honestly believe that had we turned over the documents to The

Washington Post in late 1993, we would not have had this hunt in the

press for the documents and hunting down the Clintons. We never would have had

an Independent Counsel appointed in 1994. There would never have been a Ken

Starr. And there might have been a Monica Lewinsky in Bill Clinton's life, but

I don't think we ever would have heard about her.

What did that episode tell you about the power of Hillary Rodham

Clinton?

Well, I think to be fair to the president, Bill Clinton is a man who likes

to share power and the spotlight. He doesn't mind other people doing that.

And he was very generous in bringing the vice president into a position of real

authority. I think the vice president had more authority in this

administration than any other one.

But I also think it led him ultimately into creation of what amounted to a

co-presidency in a variety of serious ways. So, that she wasn't making all

the decisions, but she did have veto authority over some important

issues.

And that put her in a situation which I think is unprecedented in American

history. You can perhaps go back to the late period of Woodrow Wilson when he

had a stroke and his wife, Edith, was making many decisions. But there's no

other, I think, comparable time when we've had, in effect, a

co-presidency.

And as much as I admire Mrs. Clinton's capacity because she truly is a very

talented woman--and she's passionate about the causes she believes in, and I

think she's a well-centered person-- but there is no room in the White House

for a co-presidency. It just does not work.

You cannot have two different camps running the White House. You can't

have a war room that goes off and does a budget and another war room goes off

and does NAFTA and then you have a war room who goes off and does health care.

You need an integrated process.

And frankly, I think the president would have been better off had he

asserted himself, his own authority, in doing that.

--private residence of the Clintons to talk to them, to make a

case for turning over these documents, what happens?

Well, Mark Gearan and I had requested an opportunity to

talk to the Clintons to persuade them to turn the documents over to the

Washington Post and Mack McLarty, the Chief of Staff, said fine. He set up a

meeting at 7 o'clock on a Friday night for us to go over to the residence and

talk to the Clintons and made it clear that there would be lawyers there

arguing the other side against disclosure because the lawyers were against it.

I knew Bruce Lindsay would be against disclosure.

So, Gearan and I go--Mark's the communications director, and,

and we're over in the residence waiting for the elevator to go up

to the meeting. The elevator comes. Stepping out of the

elevator is Mack McLarty, the chief of staff. And I said, "Mack, what are you

getting out of the elevator for?" And he said, "We're not going to have a

meeting." I said, "What do you mean we're not going to have a meeting?" He said,

"They called the lawyers over early and they heard the lawyers and they decided

they're not turning the documents over."

I said, you know, "You mean we're not going to have a chance to make the

argument?" And he said, "No, you're not going to have the chance to make the

argument."

Is that because Mrs. Clinton's view is going to hold there? That

she had held--

I didn't know. It was the first time I was really, really

furious. Because I thought "Listen this is the whole reason you asked me to

come in here was to help you on questions like this. And you don't have to

agree with me, but at least hear my argument." And, and that's when I said to

Mack, "This is unacceptable to me. I can't live this way. We've got tto make the argument to them, Mack. We've

got to talk to them." And Mack agreed. He said, it's only fair that they--and

as a result of that, that was Friday night, as a result of that Mack set up a

coffee that Saturday morning just off the Oval Office after the president had

his radio address to have a chance to talk to the president. And George

Stephanopoulos came to that meeting and he also agreed on the need for

disclosure.

So, George was there. I made a very strong argument to the president why I

felt we had to disclose the documents. George was strong. He was just right

there, saying "You really got to do this." And Mack wanted to do it. And the

president said, "Okay, I agree."

Then he turned to me and said, "Now, you've got to go talk to my wife. You

got to persuade her to do it." I said, "Okay, fine." They let me know what I

was going to be doing, and I said fine. So, that Monday morning I started

calling for an appointment. I never got an appointment. They kept on saying,

"I'm sorry, she's too busy." Too busy.

Which told you what?

It told me she made up her mind, didn't really want to

hear the argument. And it also told me that she had a veto power over this

question. And that, in fact, there were on some issues there

was a co-presidency. Now, frankly--

On what issues? I mean you say that Mrs. Clinton had veto power. She had veto power on

these Whitewater documents--but on what else?

Health care. The biggest single initiative of the first term was very,

very much her--she was driving that. I mean if anything she was the prime

player and he was not as fully engaged as he was on those other issues. And I

think that was one of the reasons that he didn't bring to bear on it his very,

very considerable political skills. I mean she's a great policy analyst, but he

has perfect pitch in politics. He can hear, he can sense, he knows, he's

finely tuned, about the political environment. I don't think that health care

bill would ever have looked the way it did had he been fully engaged, had he

been in charge of the process.

But at the end of the day, I have to say this: the tragedy about the

documents question was there was nothing in those documents that was criminally

culpable.

When the documents were all revealed, there were embarrassments in there,

but there was nothing that was going to get them into legal trouble. But the

failure to turn over the documents led to the outside Independent Counsel being

brought in. And then led to these huge investigations that consumed much of

his presidency.

Of course, there was a debate within the White House whether the

president, himself, ought to ask for an Independent Counsel. And some of the

political team were strongly in support and, in fact, the president did,

himself, ask for an Independent Counsel.

We got put in a situation where the president had no choice and we had a

long conversation. I was with him in Europe at that time--we were in Eastern

Europe and there was a phone call back to the White House with some people

gathered in the Oval Office and the president, and two or three of us, on the

line in Eastern Europe. And it was a very spirited discussion.

Bernie Nussbaum, who was the general counsel in the White House, argued

very strenuously against calling for an Independent Counsel for a very good

reason. He said, "Once you get an Independent Counsel the guy's going to have

a fishing license. He can go anywhere. It's going to be unending

trouble."

I happened to agree with that argument. You never want an Independent

Counsel because they're renegades. I mean they're sort of a runaway justice

system in some way. But because we'd backed ourselves into a corner we really

had no remaining choice. We were going to get an Independent Counsel anyway, it

was clearly going to come. So I think the president made the right decision to

say, let's go ahead and voluntarily call for one.

This is a very emotional time for the president because his mother has

died just before this. What was the mood like on that trip?

I know that the president had a great sense of loss when his mother died.

And I think that was one of those moments that you just don't want coming early

in your presidency, because it took so much out of him emotionally. But I found

him sticking pretty much to business. I didn't sense when I was there that he

wasn't paying attention to the various meetings that he was going into. When

we got to Moscow and he met with Yeltsin, he was in good shape there. He

represented the country very, very well in his conversations with

Yeltsin.

On that trip, the pool reporter gets a couple of questions and they're

Whitewater questions. The president is livid. He jumps up, pulls off his

microphone. Watching that, what was going through your mind?

This is a guy who's very tightly coiled. He's very, very tired. And he

feels he's being hounded by the press. You know, the fact was the fat was in

the fire by then. It was, you know, we were in a situation--that's why I come

back to the notion had we gotten some things right to start with, I don't think

we ever would've been in that situation. And I think that it's,

it's hard to overemphasize how important some decisions are in the White

House.

You may not see them at the time as being that important, but in retrospect

you look back and say, if we'd just done that thing, this never would've

happened.

During that same time Ted Koppel is there with a crew kind of

chronicling all this, and he's supposed to talk to Clinton every night. One

night Clinton doesn't come through, and Koppel is not happy about it. And the

next night, the president does sit down with Koppel. But when the conversation

again turns to Whitewater and you

see the president's whole demeanor change.

Yeah. It's important to understand that the president felt on Whitewater

that he was being pursued unfairly. He was just being hounded by the press and

by his enemies. He thought they had been whipped up by his enemies in Arkansas

that there was nothing really to it. And that they were using this just to

bang him over the head and he wanted to go on and be president. And I'm

sympathetic to that. I understand why he felt that.

But I had conversations with him. He said, "They are out there

investigating my friends to within an inch of their lives. They're

turning the lives of my friends in Arkansas upside down over these things and

it's not right." He was morally outraged about it because he thought there was

nothing in the Whitewater documents and the whole Whitewater episode that it

was all that difficult. But he felt he was walking around Europe in one of his

first major international outings, you know, he's got this 50-pound weight tied

to him and he can't get rid of it.

And so, this is not the way Bill Clinton likes to operate. Bill Clinton is

a free spirit. He likes to be out there, you know, sort of be able to do this

thing. And shape the world, he likes to be able to control his own destiny.

He's one of these kind of people that wakes up every day and thinks "I can shape

the world this way for me today." And suddenly, his world is being controlled

by other people and that was very, very frustrating for him.

Going back to Vince Foster's suicide, which is July of '93, you are at a

party in Georgetown that night. And then you get the call. What happens? How

does that affect Bill and Hillary Clinton?

I happened to be at a dinner over at the home of Sally Quinn and Ben

Bradlee that night. It was a large Washington dinner, one of their classic

dinners. And Vernon Jordan was there and many others. And I got a call from

Mark Gearan at the White House saying what had happened. And telling me that

the president had gone on to the home of the widow. And that was only a few

blocks away from where we were having dinner. I was terribly concerned that

this would knock the stuffing out of him totally. That he would become

terribly embittered about the Washington experience. That he would share the

Vince Foster view expressed in Vince's note that in Washington ruining people

is considered sport. And, you know, I knew that some of that burned in Bill

Clinton already. So, I was very, very worried that losing his friend was going

to knock him over. And that he would find it very difficult to govern

again.

So, Vernon and I went over to the Foster's home and what I found was that,

in fact, he's a very tough fellow, Bill Clinton is. He was not there to get

consolation from the people; he was there to give consolation. He was giving

of himself to Mrs. Foster and to the others. He was going around hugging

people, trying to buck them up.

And we then went back to the residence. Mrs. Clinton was in Arkansas. We

went back to the residence and sat there with him for maybe two or three hours

talking. Mack McLarty was there and Mickey Kantor came in and Vernon was

there, and the president was there. And I guess four or five of us.

And Mrs. Clinton called and he had a long talk with her. I talked to her and found that she was in pretty good shape. She was shaken, but pretty good

shape and was very concerned about him. But I found, in that evening one of

Bill Clinton's great strengths. He's got a resilience, he's got an inner

toughness that sometimes is not appreciated. You know, this is a man of many

talents, and some weaknesses clearly. But resilience has been one of his great strengths. He bounces back

from very tough situations. ... Not since Nixon, have we seen anybody as

pilloried as Bill Clinton was in his early months and, in fact, as he has been

through much of his Presidency.

And he's bounced back better than almost anyone you might imagine. I think

that's one of the reasons he just wears down his opponents. I mean his view of

how you wear down somebody is you show for work every day and you don't let

them get to you. And there were times, of course, when he gets angry and he

gets frustrated--

What about his, his anger? Carville said it's like a thunderstorm, it

blows in and there's lightening and thunder and then it blows out. Somebody

else called it "the wave." Did you see Clinton get angry and did he ever get

angry at you?

You couldn't be around Bill Clinton very long without seeing him get angry. I

think everybody who worked with him saw him get angry at one time or

another.

Watching Bill Clinton erupt is like watching Mt. Vesuvius. It is

something to behold. He gets very red in the face and it goes very quick and

it leaves. And he does not harbor anger. It's a way to sort of get it out of

his system.

But I don't think it's necessarily a healthy thing. I mean I think he sort

of vents. One of the reasons I came to respect George Stephanopoulos was that

frequently the president vented right into George's face. It was like he'd

just be right close and just really red in the face. It was almost as if

George was the son he'd never had. And George was very stoic about it. He knew

it would pass. And he didn't fight. He didn't try to do anything. He just

tried to calm him down and I think he helped him in that regard. But it was an

anger that was something to behold. It was not something I would recommend as

a model.

I tell you what, it's important for a president to set standards for his

staff, so they gain admiration for who he is and what he stands for and they

begin acting the way he acts. And so, what you find in our best presidents is

the staffs get very much shaped by the atmosphere in the White House and

the way the staff behave begins to take on the coloration of the person in the

center. And if you've got a president who sort of is a little erratic, you

know, he's very bright, but he's not as steady, the staff can get very

erratic.

One of the things Bill Clinton did that I find most unfortunate, was he

lied to his own staff about things during the campaign. He lied about Gennifer

Flowers, he lied about the draft. And once you start down that road, what you

find is "Well, if he's going to do it, maybe that's standard operating procedure

around here." And he wasn't--

Was it? Did you find that in the White House? Did you find people were

lying?

I think that the vast majority of people who worked with Bill Clinton and

have worked in the Clinton administration are honest, up, straightforward

people. I think there have been some people around him, a few, who have been

willing to engage in a lot of things that are just unethical. I don't think

there's any doubt about that. I don't think you can look at the record over

the last seven years and say there hasn't been a pattern of unethical activity.

Now, it has not amounted to an assault on the Constitution of the kind that we

saw in the Nixon Administration. I was there in the Nixon Administration. The

violations of law, the abuses of power were much more serious but one can't

look at what happened in the Clinton administration and say this has been a

good record. It has not been the most ethical administration in history, I'm

sorry to say.

And I think that some of this starts at the top. I really

think it's important for a president to set standards and say, you know, "This

is the way we're going to be. This is the way I'm going to be and the way I

expect you to be and if you're not, if you don't behave yourself, you're out of

here."

I think it's really important for a president to do that. Our best

presidents have done that. And you know, the

coloration of the person in the center does matter a great deal. And I

think Bill Clinton has done some fantastic things for the country. In many ways he's had a lot of accomplishment, but there have

been some downsides. And you just can't walk away from them and say, it's been

all perfect. It hasn't been.

One of the trademarks has been a tendency to sort of lurch from crisis to

crisis to go up to the brink and pull back. And whether it's legislative

fights or the draft or Gennifer Flowers, there's always been a crisis, where

doom is right around the corner and yet, Clinton pulls out of it.

Is there something about who Bill Clinton is that leads to that kind of

lurching from crisis to crisis?

That's a good question. There is a part of him, because he's so bright,

that becomes easily bored. And I think he enjoys to some extent seeing how

close he can walk to the edge of the envelope and still pull it off and still,

you know, walk right on the edge. And his problem has been as president,

occasionally he's fallen off.

But there's a part of him that sort of likes to dare history, because he's

always been so good and people have always been able to say, "Wow, he did

that." I think it's sort of one of the things he enjoys doing. He likes to

get the ball on his own two-yard line and see if he can score a 98-yard run.

He just enjoys that. And it's part of his psyche.

And so, I think he's willing to accept a certain amount of chaos or a

certain amount of lateness on things and try to pull it out. It's like the guy

who doesn't study until the night before the exam and then reads five books

and goes and gets an A. I mean, that's been his history in life, right? So he

brings that to governing. And he's always succeeded in life doing that.

The presidency is a very, very difficult institution. It's very difficult

to govern this country. It takes a lot of discipline and a lot of thought

about where you're going. And if you lurch around what happens is that you

frequently get some things done, but it leaves the rest of the community

saying, what's going on here?

Forty years ago Richard Neustadt published a book about presidential power

that's now the classic in the field. And he made the observation that you have

to have two things going for you. You have to have public prestige and a

professional reputation. Now, Bill Clinton has been very good at the public

prestige. He's been very, very good at the outside game of politics. Better

than almost anybody we've seen recently.

He's had a much, much harder time on the professional reputation.

Professional reputation is how people feel about you on Capitol Hill, how

people feel about you in the press, how people feel about you in Georgetown,

and some other places around Washington, increasingly it's how people feel

about you in New York and in Silicon Valley and in Redmond and in places like

that.

And his professional reputation has been one of "We're not sure who he is.

And we're not sure he'll be there for us in the end." And there's been a lot

of distrust up on Capitol Hill and I think that's come back to haunt him. I

mean I think he's been much more popular in the country than he is in other

power centers. And that makes a difference in governing.

Foreign policy. One of the great successes was the Rabin-Arafat

handshake, but one of the most difficult times was Somalia when the president

sees the pictures of American Delta Force being dragged through the streets of

Mogadishu. What was it like or what was the president's mood, what was he

saying when that crisis was breaking? And that was on your watch.

He was extremely upset about the loss of life. ... He's been very willing

to use American forces overseas but he's been very reluctant to see them go in

harm's way or be put in a situation where a lot of people get killed. He's

tried to calibrate carefully various U.S. engagements so that a minimal number

of people get killed and it's still an exercise or a demonstration of

force.

Somalia wasn't quite his Bay of Pigs, but it came close. It was a

situation in which I think he in retrospect realized that as president he had

allowed the mission to expand, what's called mission creep, and at the same

time he had been withdrawing down the number of forces who could do it. And he

left his forces in a situation where they were overexposed to danger. And he

knew that. And in retrospect, I think he blamed himself to some extent and I

think to some extent he blamed some of his advisors.

Was there a sense there when you were with him that we were going to get

out of there as soon as we could, that we were going to cut our losses and

leave?

I think that Somalia haunted the administration for a while after that.

It was almost like the Vietnam Syndrome. There was a Somalia Syndrome. And

that is, don't ever get yourself in a situation like that again where you put

people in harm's way and they are not fully protected, you don't know what

you're doing.

I was trying to remember whether the Haiti thing came after that.

It did. Yeah. It did. As I recall we had a ship going into Haiti, the

Harlan County, and they got there and there was a mob on the pier. And

to my astonishment, people in the Harlan County were not armed. And I

said, look--and people blame me for some of this, but my argument to the

president was-- "You got one of two choices. You either got to go in with

force and take care of that unruly mob, you can take them in five minutes. Or

you got to get the ship the hell out of there."

The one thing you cannot do is dither. You can't just leave that ship

sitting there while you try to figure out what to do. And he ordered them out

.... And frankly, I don't blame the Harlan County on Bill Clinton so

much. I don't understand why the Pentagon didn't have those people armed going

in. They weren't prepared for what amounted to be like a street mob.

...I want to come back to this. The Somalia Syndrome was playing into the

Harlan County episode. Because nobody wanted to have Americans leave

the Harlan County and go ashore unarmed and get killed by that mob. That would

have been awful, and in the back of people's minds was Somalia. And that

existed in the back of people's minds for a long time.

You got to remember the people who were around Bill Clinton have a real

neuralgia about Vietnam, that Vietnam continues to play through in this

generation. This is the generation that is now in power. They grew up in Vietnam. And

Tony Lake, his National Security Advisor, was in Vietnam. And Tony takes this

very, very seriously, and to his credit.

Tony Lake is one of the kind of people who quietly, as National Security

Advisor, went to the funerals of people from Somalia and took his day of Sunday

and flew to Kentucky, I think it was, to go privately as a citizen to the

funeral. Very quietly and came back. Didn't say anything about it. Didn't

want any publicity. But the loss of life was very, very important to the

president and the people around him, loss of American life.

To what extent during your tenure did Bill Clinton care about foreign

policy?

You got to remember when Bill Clinton was elected the country thought

George Bush was spending way too much time on foreign policy and wasn't paying

enough attention on the domestic side. So Bill Clinton came in with the

understanding of the mandate from the country that was pay attention to the

domestic side and forget this foreign policy stuff.

And the truth was it flipped between the Bush administration and the

Clinton administration on the attention to foreign policy. Traditionally where

presidents have spent maybe 60 percent of their time, 65 percent of their time

on foreign policy during the Cold War. With Bush he got up to about 75 percent

sometimes. With Clinton it totally flipped and he went to maybe 25 percent of

his time on foreign policy at most.

Jim Woolsey, the CIA Director, couldn't get on his schedule to see him.

Couldn't get in to see the president?

Couldn't get in. The CIA does a daily briefing with the president. And

that's long been the case. And so, Jim Woolsey would come over with his

briefers thinking, "Well, I'll get a chance to go in there and talk to him."

They had a very hard time getting on his schedule. When the little tiny plane

crashed on the White House lawn, the joke around town was that was Jim Woolsey

trying to get an appointment to see Bill Clinton. And other governments were

having a hard time getting on his schedule.

Now, when he got in trouble over five or six months, Tony Lake and Warren

Christopher and others, Sandy Berger, were able to persuade him, "Look,you're

good at this foreign policy stuff. You know, you went to school at Georgetown

on foreign policy, you enjoy it. But you're not spending sustained attention

on it and you really need to do that." And they began correcting that schedule.

But for the first few months all the emphasis were somewhere else. And I have

to say his attention span on foreign policy remained episodic through much of

his presidency. But I think he was better on foreign policy than he's given

credit for. I think he's had many more accomplishments than he's given credit

for.

Just before Christmas in 1993, the trooper story breaks, first in The American

Spectator, then in The Los Angeles Times. How did Bill and

Hillary take that story?

That was a tough, tough blow. He acted outraged, and she was clearly

outraged; wouldn't say so, but I think she felt a sense of humiliation that

went very deep. No first lady likes to be put in that situation, of course.

So, it was a very tough time for them.

And she in that kind of environment, her first response is to rally the

troops and get people out defending the president. I think that's one of the

great contributions she's made to him over time. She's the one who steadies

things up. She deploys people, gets them out there.

But I think it was privately just very, very difficult for her. Now, I

believe that the Troopergate story was a turning point on the health care

fight. Let me explain why. Up until that time, she had been very, very

involved in sort of the effort to put together the health care plan. It had

been early presentations in the fall of 1993. The Troopergate story came along

in December. I think it put him in a substantially one-down situation, with

her psychologically in the dynamics of a marriage.

I can't prove this. My sense has been they are on a see-saw in their

relationship. When that relationship works, they're very good partners. But

when she goes up and he goes down, or he goes up and she goes down, there, the

balance gets out of whack. On health care, what happened was that that

Troopergate story put that see-saw up so that she went way up and he went way

down. And I never saw him challenge her on health care in the weeks that

followed. On the politics of what was going on, on sort of how to get it

presented to the Congress properly. How to get it through the Congress. I

really think that it sealed her position. It put her firmly in charge of how

to get health care done.

Is this because he's in the dog house? Is that what you're saying

here?

Absolutely. Watching him in that time, it was very much like watching a

golden retriever that has pooped on the rug and just curls up and keeps his

head down. And it put him in a situation where he was in her dog house. And I

think it put him in a situation where on health care he never challenged it in

a way he ordinarily would have, had he been under different psychological

situation.

And, of course, the Troopergate story set off the Paula Jones case. Paula

was mentioned in The American Spectator story and that led to the

lawsuit. So it had other consequences. But it had a real change in the

dynamics I sensed, at least in the White House, and it couldn't have come at a

worse time. It was really very, very damaging.

I don't want to put the blame on her on health care. I don't think that's

fair. I don't think she ever should have been asked to put the health care

thing together. I think Donna Shalala should have been asked to put that

together and I think Mrs. Clinton could have led the crusade to get it passed.

But ultimately this was Bill Clinton's White House. He was the guy elected

president. Ultimately if your wife gets assigned health care that's his

decision.

And so, you have to say Mr. President, you did a lot of really good things

as president but turning the health care program over to Mrs. Clinton, who had

never really worked in Washington before and asking her to do something that

massive was like giving her a mission impossible. It just was more than she

should have been asked to do. And I do think that the dynamics of the

relationship had something to do with it.

You mention Troopergate leads to Paula Jones. She gives this press

conference and there's a sort of interesting strategy that develops from the

White House.

The president's lawyer had a good line on the lawsuit, this was "tabloid

trash" with a legal caption on it. You also had a not-too-subtle attack on

Paula Jones herself. You have James Carville out on the talk show saying,

"Drag a hundred dollar bill through a trailer park, no telling what you're

going to find."

So, here you have the White House attacking the press again, shaming the

press, and attacking the integrity of the woman bringing the charges. What was

your view about the strategy?

I'm the wrong person to ask. I was not there for that. I had left by then,

but I think the record is pretty clear that by attacking Paula Jones personally

that the prospects for getting a settlement went down the drain. That she felt

insulted and pushed on. I think they were very, very close to getting a

settlement from everything I've understood about it. And by attacking her it

really went down the other way. And James Carville has been a first-rate

political strategist and helper for Bill Clinton over a long period of time and

a big, big defender of his. But it's up to the president to determine how he

wants the people who are loyal to him to support him. If you took a Franklin

Roosevelt in that situation he would not have allowed somebody to go after

Paula Jones in the way they went after her. He would've understood "Let's cut

our losses. Let's get this behind us. Let's get a settlement done and get

this woman out of the headlines. We don't need this."

And, instead, by going out and attacking, I think you you get her into a

situation where it goes the other way. Now, I want to contrast that--and this

is a very interesting point and it may seem like a stretch.

Contrast that to the way Bob Rubin worked with Bill Clinton on the Alan

Greenspan relationship. Bill Clinton's tendency was to go out early on in his

presidency and go out and attack Alan Greenspan on interest rates. He thought

they were way too tight and thought they were holding back the economy and he

wanted to go out there and attack him. And Bob Rubin came to him and said,

"Mr. President, you can't do that. If you attack him, you'll challenge his

manhood and if you challenge his manhood he's going to tighten some more just

to show you that he's independent."

And Bob Rubin understood and as a result the president listened to that,

decided that is right, that's wise, didn't attack him. And lo and behold

Greenspan got us through this thing and they've had a fabulous relationship

since, and Bill Clinton has twice reappointed Alan Greenspan. And it's been a

terrific economy, partly because of that relationship. I think if they had the

same kind of restraint with regard to Paula Jones that they had toward the Fed,

there would have been a very different outcome.

By the end of '94, I mean you've been brought in as you say largely to

bring this president back to the center. There was a profile problem he had

after his early couple of years. He had gone way to the left and Hillary was

blamed for part of that.

I think it was partly to get him sort of righted, to help get him out of

the ditch. His presidency had gone into a ditch and my job was to help him get

out of the ditch.

One of the things that you were arguing for strenuously to do was NAFTA.

Why was that such a critical moment for Clinton at that time?

NAFTA, in my judgment, was one of the finest hours of Bill Clinton's

presidency. And people like Bill Daley and Rahm Emanuel, and others--Mickey

Kantor--deserve a great deal of credit for. What was really important about

NAFTA was, first of all, it was good policy. Secondly, and very, very

importantly, it was courageous of Bill Clinton to go out for NAFTA because he

had the labor unions all on the other side. His entire political base was

saying, "don't do this." He had a lot of people in the White House saying,

"Don't do this. This is a loser. You're going to lose this thing and you're

going to really tee-off your base and they're going to leave you."

And he said, "No, no, it's good for the country" and he went out and fought

for something. And he showed people that he had some guts. He showed people

that when it came to sort of, "I'll do something because if the country's

interest is at stake I'll fight for it." And I think that was a terrific

moment for him. I think NAFTA, passing NAFTA and getting the budget bill

passed the first year were like two of the most important moments of his

presidency. And they sent a signal to an awful lot of people, but particularly

NAFTA sent a signal that at the end of the day Bill Clinton was not driven

entirely by polls and by politics, he had some guts and he had a sense of what

was best.

The tragedy that came later was that after he lost the 1994 elections and

the Republicans took over--that Dick Morris who was the master strategist and I

think one of the cleverest people who's ever been around Bill Clinton and has

the best insights into Bill Clinton as a politician--the tragedy was that Dick

Morris persuaded him he had to get away from that kind of thing and he had to

go very political in order to survive. And he moved away from those kind of

efforts.

I think if he'd stuck to his guns as he did on NAFTA, I think he would have

sent a lot of signals to people that this is a gutsy guy.

You were still around at the election of '94?

I was over at the State Department by that time.

By this point Clinton is sort of upset with his whole team. There are

big, big changes in the White House. What was his feeling? I mean why did you

get moved to the State Department? Did he tell you?

I asked to leave. I wanted to get out before the '94 elections. I had

told him when I came in I didn't want to be around for elections. I could help

him with the governing but I thought it was inappropriate for me to be there

for an election period when inevitably it was going to get partisan and I had

worked for Republicans. I just didn't feel comfortable about that...

Did you talk to him after the elections? I mean did you get a sense

from him--

Yes, I talked to him. He went through another downward spiral. This

presidency has been on a roller coaster from day one. And what you find is in

year one he starts high coming off the transition, 59 percent, he goes way down

the first six months, he brings himself back up, and then he gets health care

and he goes down and then he gets the defeat in '94 and he goes way down. And

with Dick Morris there he picks himself back up again. And then, of course, he

goes down after the Monica business and he has never fully--

Did he take any responsibility, himself, for losing the Congress in '94?

Did he ever face that he was partly responsible for that?

He was really, really angry at just a variety of things. He was angry at

the Republicans, he was angry at the consultants. And he felt that if this the

way that politics is going to be played in Washington, by God, he'd play it

this way. His view was the Republicans have been cynical all along about

politics, "They come in here and they don't stick to their guns, they just do

the things that are political so they can get reelected. I came in the first

two years and tried to do the right thing for the country, got my head handed

to me. And by God, I'm not going to do that again. I'll do what basically I

need to do."

He was very much fighting back to get elected. And that's why I think

Dick Morris understands that. Dick Morris said--he's written in his book he

wrote--"You got to understand that there are two sides to Bill Clinton.

There's the good government Bill Clinton, and then there's the guy who's the

politician. And if his survival is challenged he's going to turn into a

politician." But that's what happened after the '94 election.

Why did he get rid of his political team?

He thought they had let him down. He thought that they had misjudged the

tenor of the times. I think he blamed them in part for health care that they

had been deeply involved in. I frankly think that they paid a bigger price

than they should have. I think these were very talented people. And they had

served him well over a long period of time. But hey, look, it's, like a losing

baseball team, you fire the manager, get a new manager. That's where he

was.

Looking back now, what do you consider his legacy to be, his historical

legacy?

I think historians are always going to be ambivalent about Bill Clinton,

just as they are about Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon. And that's because

there is a bright side of Bill Clinton who has accomplished enormous things for

the country. The country is clearly better off than it was the day he was first

elected.

The 1990s are going to be remembered as one of the brightest decades of the

20th Century. And he was one of the prime movers in that decade. Many of the

steps he took were small, to be sure, but the decade turned out very well.

We're better off economically, we're at peace, and a lot of cultural indicators

like divorce rates, teenage crime, teenage pregnancy, are moving in the right

direction.

And he has something to do with that. And, yet, at the same time, there is

this other side, the downside, the negative side. He goes in the history as

the first elected president to be impeached. He goes into history as the first

president who's had his whole sexual life thoroughly opened up in the press.

He goes into history with an administration that has a very tainted ethical

record, just whole episodes that have bedeviled him.

Nothing as serious as Watergate. But the whole conjure of things we call

Whitewater, you know, have left a definite stain on it, and I think historians

are going to have a hard time with it. I think they are going to have a hard

time sort of juggling how you weigh those two things in the end.

And Lyndon Johnson's always faced this. Now, what's happening with Lyndon

Johnson is that he paid a heavy price in the beginning on Vietnam and now he's

being recognized for what he did in civil rights and his reputation is getting

better. I think Bill Clinton over time will fare better in the history books

than he will immediately. I think he's going to look better over time. I also

think that the country is better prepared for the 21st Century than we think we

are. We are in better shape as a people than we think we are. And I think

people will look back and say, "You know, Bill Clinton told us about this

bridge and we never understood what the hell it was, but it turned out he

prepared the country." Over the time he was president a lot of things happened

that made us better prepared for the 21st Century. And I think he'll get some

credit for that.

And this gets a little esoteric, but let me just put this over. Bill

Clinton has introduced a different kind of leadership to the presidency. We

traditionally like leaders who are very strong and have a sense of direction

and go right this way and here, "Follow me." He has almost a feminine kind of

style. It's more like "Bring this in, get this viewpoint, get this viewpoint,

and we'll sort of synthesize everything and we'll try this and we'll move

forward."

And I think we're seeing more and more of leadership like that in the

corporate sector and in other kinds of organizations, in which there are many

more voices at the table--the diversity that he's introduced, and looking for

additional voices, trying to bring other voices in. I am a traditionalist. I

prefer, "Let's go this direction." But I think there is an argument to be said

for someone who has a 360 degree vision and draws the best from various

traditions to put it together. And I think we're going to see more and more of

that in the future.

In May, I had the opportunity to go to the White House and hear Bill

Clinton speak extemporaneously and he was like the best I'd heard him in a

long, long time. I couldn't believe it. I went to some of his people and said

"Has he been speaking like this recently?" And they said, "He's entered a zone

in the last few weeks that nobody quite understands, but its like a baseball

player who's on a hitting streak. And the baseball player gets in that zone and

he sees the ball coming toward him from the pitcher bigger than it really is

and can hit it more easily."

And somehow he has been liberated. And over the course of his last year,

he's willing to talk about things he would never talk about in a way. He's

willing to talk more about himself. I think he's coming to grips with sort of

his own place in history, who he is as a person. I think he's a much more

mature man now than he was when he was first elected.

In my judgment he went on this roller coaster ride that was in his

presidency. It was the first four, five, six months when he went straight down

and then over the next several months he pulled himself straight back up again.

And he was the prime architect of his recovery.

And then the Troopergate thing hit and then health care went down the early

next year and then he lost the Congress and then he went right back down again

on the roller coaster. But to some extent what you have to understand about

the presidency is, you don't have long to make your big accomplishments. When

Lyndon Johnson was elected in 1964, he went to his people and said, "We've got

about a year to get things done." Because power slips away in this office, it

evaporates very quickly. And the problem with coming in with those big early

losses and going down on the roller coaster those first six months, he's lost

precious time.

That first six to nine months in the presidency are the most important time

you have as president of the whole eight years. That's when you can get more

done with the Congress, that's when you're fresh, when the country's with you,

things haven't hit from the outside. And inevitably, in every presidency,

you're going to have some things that come in from the outside that come

banging on you which you can't expect. And so things that happened to him late

in the first year--Vince Foster happened in the middle of the year, he couldn't

help that, or The Los Angeles Times and the Troopergate story. Those

outside things come up and banging up against you. And if you don't get it

early, you don't get it. It's really hard.

I think the strength of Bill Clinton is that he could overcome. Most

people in that job would never have been able to pull out of that first

tailspin that he went into. But he did. And that's the remarkable thing about

Bill Clinton--how good he is at pulling himself out of the tailspins. He is

"the Comeback Kid." The other remarkable thing about Bill Clinton is how he

gets himself into trouble so he goes in those tailspins. And that's what's

been hard to reconcile.

As you were saying before, there is a part of his character that seems

to enjoy living dangerously.

Yes. He likes to live dangerously. It's the eight years of living

dangerously. Some really high points, some very strong things, but he likes to

live life right at the edge. And there's something about him psychologically

that has thrived on that all his life, Now, I happen to believe that he's

coming out of it. I sense a man who is coming more into his own than he has

been any time in his life. That he's coming to grips with himself in ways that

he has not before and it's healthy. You know, as a person, I think he has

always believed, as a Southern Baptist, in the powers of redemption and I think

he's in the process of sort of pulling himself together.

|