September, 1997....there's another inspection team in country... a biological

inspection team, headed by a scientist named Dr. Diane Seaman.

UNSCOM is full of unique characters, and she is one of the unique characters.

She is a coldly efficient woman, a warm human being but, man, she is

professional as the day is long.

And Diane was doing no-notice monitoring inspection. And normally, a team

would show up, and you arrive in the front of the building, and the Iraqis

greet you, shake your hand, you go in and you have a cup of tea with the

director, you talk about your program, then you go off and you monitor the

facility.

Well, Diane said, 'I'm not going to play that game this time. We're going to

show up and we're going to go straight to the back stairs and go upstairs, and

see what happens.'

As she got upstairs she ran into two guys coming downstairs who had briefcases.

They saw her, she saw them, they tried to bar the door and run. She said, 'No,

not in my lifetime,' and she got the door open. Imagine it: These are two

burly, Iraqi special security organization personnel, running away from little

Diane Seaman. She caught them, she intimidated them, she was the alpha dog.

She got them in the room, and got the briefcases from them.

She opened up the briefcases and started rifling through, and the first thing

she sees is the letterhead of the Special Security Organization. Now... if you

see something about the S.S.O., that's critical. And she went, 'Ritter told me

about that, this is big.' And she starts flapping through, and she sees

biological activity staff of the S.S.O. Man. Looked through more: Clustering

and gases, gangrene, something the Iraqis had weaponized, a prohibited

bio-toxin.

No further questions. Locks it up, hands the briefcases to one of her

inspectors, says, Take them down to the car and get out of here. And the guy

got out, and as he was going down and getting in the car, the big Iraqi team

came up, burst in, said, 'We want the briefcases.' Too late, Diane had already

taken them back to the BMVC, where they were studied more.

One of the sites that we had wanted to inspect was the Al Hyatt building. We

had information that it was the administrative offices of the Special Security

Organization and we felt that certain activities, to include the biological

activity, were being conducted there, at least staff was headquartered there.

And Richard Butler had decided that that was too confrontational, and that he

was going to scratch that off of this inspection.

But I now have documentation [from Diane Seaman's discovery] which justifies

this kind of activity. So I worked with Diane and we coordinated with Richard

Butler, and we confronted the Iraqis at an evening meeting. And Richard

Butler said, If the Iraqis don't answer your questions, you're authorized to do

a night inspection of the Al Hyatt building.

So, we go in, and we start meeting with the Iraqis, asking questions, and

they're not giving us the answer we want. So, after a while I interrupt the

meeting, I say, Look, we can do it the easy way, or we can do it the hard way.

The easy way is, we ask a question, you answer it to our satisfaction, and

we'll confine this discussion to this room, and we'll be done tonight. The

hard way is, we ask a question, you don't answer it to our satisfaction, and

then we're going to run a night inspection, and I'm telling you, you're not

going to like it. And they were like, But you said your inspection was done.

I said, You can start it again in a heartbeat, by not cooperating. So, we go in, and we start meeting with the Iraqis, asking questions, and

they're not giving us the answer we want. So, after a while I interrupt the

meeting, I say, Look, we can do it the easy way, or we can do it the hard way.

The easy way is, we ask a question, you answer it to our satisfaction, and

we'll confine this discussion to this room, and we'll be done tonight. The

hard way is, we ask a question, you don't answer it to our satisfaction, and

then we're going to run a night inspection, and I'm telling you, you're not

going to like it. And they were like, But you said your inspection was done.

I said, You can start it again in a heartbeat, by not cooperating.

Apparently, they might have thought we were bluffing. We asked the question,

they didn't give us the answer, we terminated the meeting and went back, got

final authority from Richard Butler, and now we assembled an inspection team to

go to the heart of the presidential palace area in Baghdad, where Saddam

Hussein lives and works. In the middle of that is the Al Hyatt building, where

the Special Security Organization had offices.

And we take off in a convoy of about 14 vehicles, Diane Seaman, me, the rest

of the inspectors. Now, in the front of me is a vehicle driven by my operations

officer, the brilliant Chris Cobb Smith, a former Royal Marine, artillery

gunner, courageous man, a brilliant planner, and he's navigating us in. He and

I had spent hours looking over U-2 photographs, picking the best route in.

So, he's leading the convoy in, as navigator. As we approach the turn-off to

the Al Hyatt building, we come to an intersection. Now, we had anticipated

that there would be a roadblock there, but there wasn't, the road was clear,

light was green, so Chris' vehicle starts snaking through. Light turns yellow

at that point, so Chris accelerates through, because standard operating

procedure is, once a convoy commits through a traffic light, we all go through.

Normally, what the Iraqis do is block traffic to get us through. We don't want

to have a convoy split, in the city.

So, he accelerates through. As he accelerates, an Iraqi Special Republican

Guard, one of the elite troops protecting Saddam Hussein, who's supposed to be

manning this roadblock, had apparently been snoozing on the side, wakes up and

goes, My God, cars. So, he comes up and he slaps Chris' car, but Chris just

kept going. He turns around, and there's my car. Now, I have a French driver

that night, a French military officer, whose command of the English language

was limited. And I look at the situation. The guy's got a gun. And I said,'

We might want to stop the car right now.' And he keeps going, towards this

soldier. The soldier's screaming, shrill voice, panicked. I said,' We really

might want to stop the car right now, go ahead and stop the car.'

He keeps going, straight at the solider. The soldier locks and loads his

weapon, puts it on fire, gets down into a crouch -- I mean, he's ready to fire.

You see him bracing, and he's screaming.

I turn, and I scream at the top -- 'Stop the damn car, you son of a bitch.'

Stops. The guy's screaming, getting ready to shoot, and I'm thinking, 'That's

it, we're dead,' when this flash of green comes off of my right shoulder. It

was one of the Iraqi minders, the people who escort us, and he jumps between me

and the soldier. A spilt-second, I think, we would have all been dead. The

solider now has it, and he's screaming at this guy, getting ready to knock him

off.

Meanwhile, another guy comes up, a Special Security Organization uniformed

officer, pulls his pistol, points it at this Iraqi colonel, then points it at

me, he's got it leveled at my head, and he's going back and forth, the

soldier's going back and forth, screaming at the top of the voice, and I'm

thinking, 'This is really interesting.'

Chris, meanwhile, is zipping on, and three Iraqi vehicles were following him at

high speed. So, Chris is moving on fast, and in front of him there's another

check point. And you see guys pulling out RPGs, rocket propelled grenades,

loading machine guns, getting on their knees, ready to shoot. I grab their

radio, and I don't want to make any sudden moves because I've got these two

goons, who are very nervous: 'Chris, you might want to stop the car, these

guys have guns. '

And Chris had an Australian driver, a military guy, at the wheel, who's a very

cool character, and slowly, without screeching the brakes, stopped the car.

The Iraqis come in front of him, and we finally get Chris back, and the

situation calmed down, somewhat.

Later on, we had more S.S.O. guys come out, and they were not happy about us

being here. These were big thugs come out, and they're all waving their

pistols around, and a lot of guns in the area, a lot of testosterone and a lot

of adrenaline and a lot of energy. And it was a very, very tense situation

there for a while. We got it calmed down and we were able to get people

focused on the matter at hand, which was, do we -- are we going to be allowed

to proceed to the Al Hyatt building? The answer, in short, was no.

But it was a tough situation, and it's about the closest, I think, we came to

getting a lot of people killed. It was just that close.

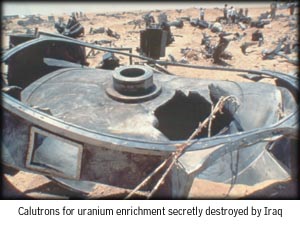

The first week of the inspection [in June 1991], we played by the rules that

the I.A.E.A. had before the war. We would tell the Iraqis that the next day,

'we would like to inspect this area.' Of course, the next day they wouldn't

allow us in, and ultimately would lose the material.

Finally, after a week, I decided that we're going to use the full powers we

had under the UN Resolution 687 and carry out a no notice inspection.

Because otherwise we weren't going to find anything. So we suddenly appeared

at the gate of a military facility and demanded access.

The poor commander of the base that day said, "I have no orders to let you in."

But he made what turned out to be a genuinely fatal mistake for him. He said,

"You can put up as many members of your team as you want to on this water

tower, which is right inside the gate." So I had four of my daring-do members

climb this 50 meter water tower, and literally-- because we video-taped this--

if you look at the timeline of the video, it's about 90 seconds into it and it

looks like dinosaurs rolling around the back of the base, there's so much dust

being stirred up. What had happened is the calutrons were stored on these

very large tank transporters, which are about 90 feet long, actually, some of

the bigger ones. And they were charging out the back of the base.

Now, this was a problem for us, because the photo interpreters had told us,

"Don't worry about covering the whole perimeter of this huge base, because

there is no rear entrance. Well, there was a rear entrance. It was a very

small one, but the Iraqis decided to use it, and that's what kicked up the

dirt. So I had the team split and go around the base to try to get parallel to

the calutrons being moved, and stop them or photograph them. In the process,

the Iraqis decided to fire shots over their head, but we did get the

photographs. And the photographs are damning as to what the Iraqis were

doing.

The humorous story.. is, we threw together these inspection teams. There was

no preparation during the war for them. So it was come as you go with whatever

equipment you had. Rich had managed to bring his family's camera, the only

camera he had. And his wife had told him before the mission, "One thing:

don't lose this camera. This is our brand new camera." So the Iraqis, after

firing shots over their heads, stopped finally, ran the team off the road, and

demanded the cameras and the film. Well, Rich, at that point, had secreted the

film in a place that the Iraqis were unlikely to easily find, but he didn't

want to give up the camera, so he managed to convince the Iraqis, "It's not a

camera. It's binoculars." I later told him, "Give up the camera. We'll chip

in together. It's the film that's ...(inaudible), not the camera." But he

remembered his wife's charge to him.

And that [inspection] was a turning point... the senior officials of the

I.A.E.A., including the Director General, had wanted to declare that Iraq was

in total compliance, because we had in the first mission found everything that

they had said they had. And it was only because a few of us were determined to

look at the evidence seriously and really see if in fact we had found

everything-- that we had a second mission. Well, this was proof that no one

could deny. It was physical evidence of a very, very large uranium enrichment

program. And it was also the evidence of concealment, that from the very

beginning, the Iraqis had not been living up to their obligations. And you

couldn't deny that.

Starting in July [1991] we had evidence from a defector that they were

consolidating documents [describing their nuclear program], and some evidence

as to where the site was...

By late August, early September, we were convinced that, in fact, we knew where

the documents were, and we decided to conduct this inspection mission. This

was a mission going after the very heart of the program, and in fact we were

lucky....

We got the documents, and the Iraqis were astounded. In fact, one of the

documents we got is still an amazing one-- an order to the Iraqis two weeks

before we arrived, saying that I would be leading the team. They thought we

would be going after the documents and they were ordering the Chief of

Security to the building to empty the building of all sensitive documents. He

wrote back on the bottom of the memo, "I can't do it in this time frame." And,

thank God, he wasn't successful in that time frame. We suddenly were in the

building, and the Iraqis realized we had the damning evidence, the full extent

of their program. And this was laid out exactly in black and white that they

were proceeding to produce a nuclear weapon. Not just enriching uranium, as

they claimed: "Well maybe we did that. But we didn't have any intent to

produce a weapon." This described their progress in great detail towards

producing successfully designed nuclear weapons.

And so they kicked us out of the building, literally, by force, and said, "You

can leave the parking lot, but you're not taking these documents." We said,

"If the documents don't go we're not leaving the parking lot." And so, that

was the source of that standoff. The determination of our team of

international inspectors that their mission was sufficiently important that

they were willing to be hostages, or as the Iraqis preferred to refer to us,

"guests of the state," in a downtown Baghdad parking lot.

If you're in a situation like that, you survive by two things. A), you've got

to go through the normal bureaucracy of filling out reports anyway, so you keep

the team busy that way. And you think of how you make the Iraqis more

uncomfortable than they're making you. That is, you don't let the pressure

focus on you. I mean, it was dangerous, from our point of view, for us, but

you forget, it was also dangerous for the Iraqis. Here they had a group of 43

inspectors stuck in a parking lot, not letting them go. They didn't know how

the U.S. and the Coalition would respond. And we kept trying to emphasize to

them that they didn't know how, and that it could be dangerous for them. We

had the advantage--it was the first time that satellite communications made a

difference to an international inspection.

I had the rule, on every inspection I led, that as soon as we got to wherever

we were inspecting, we set up a satellite telephone. Now, in the first

mission, it was two suitcases-- two huge suitcases. By the time of the

September mission it was the size of a modest sized briefcase. That's how much

the technology had progressed. So in fact, we were in communication with the

rest of the world. People could and did call in from wherever to ask to

interview. So we did that as a means of keeping the world informed of what the

Iraqis were doing. The Iraqis had no way of understanding the power of the

world's media and the larger public as they focused on that issue. And by the

time they figured out that this probably wasn't in their interest-- We now

know they considered taking out our satellite communication capability, but

they were worried. How would the world respond if suddenly we went off the

air?

And we did that. We played on that as a means of keeping pressure on them.

Now, let me say, we got out of that parking lot not because of communications;

we got out of that parking lot because the Security Council was united behind

the inspection purpose. And that's the real difference of what changed over

the eight years. When I came out of that parking lot raid, I went back to a

private member meeting of the Security Council. The first two states to speak

in support of what we had done after I finished a briefing, were Cuba and

Yemen, neither states generally friendly to the United States nor personally

friendly to me at any time in my career.

They were united. This was not something led by the United States or the

British. There was a strong Security Council purpose there. And my great

regret is, in fact, that purpose is gone now. And I think that's what's

happened to UNSCOM. The Coalition has fundamentally fissured.

Back then, the world was worried about Iraqi nuclear weapons. There was a

period of optimism that if in the post-cold war world, that the Council could

act together, it could deal with the threats of the peace. I guess in

retrospect, maybe it was naive optimism that the UN Security Council could do

the role that was intended for it in 1945. In '91, '92, that still prevailed.

But certainly by '94, '95 and now in '99, that optimism is gone. It's gone as

a result not only of Iraq, but because of Somalia, as a result of Rwanda, as a

result of Bosnia and Kosovo now. And fundamentally, as a result of Russia

falling apart.

One last thing on the parking lot incident. You're surrounded by the

Iraqis, and yet you're on a satellite phone to CNN!

That's correct. You know, that's the power of communication. In fact, it's

the first time I personally realized, the Earth really is round, because you

would sit there, and not only was it CNN. You'd do the Japanese morning

television news, the Australian-- I had a very accurate understanding of where

the sun was at any one time, because of the schdule of morning and noon and

evening newscasts.

"Live from the Baghdad parking lot, David Kay."

Well, my favorite interview was actually a Chicago radio station called in and

asked what we really wanted. I said, "We'd really like some pizza." Because

we were existing off of MRE's and there was a promise, "Well, don't worry.

When you get out of the parking lot we'll see that you get Chicago pizzas."

We're still waiting for those pizzas, as the matter of fact

[But] I think the Iraqis were genuinely worried about military action being

taken place. And that's why they didn't take the satellite telephone down.

"Shake the Tree" was, you could say, the last desperate effort of UNSCOM to

break through Iraq's concealment mechanism. You had in Iraq many overlapping

layers of special services, whose principal job was to foil UNSCOM's work; to

anticipate where UNSCOM would go, to build cover stories, to evacuate the

material. There were networks of temporary and more permanent hide sites.

Sometimes they tried to develop a good cover story for UNSCOM, and sometimes

they didn't even bother. Toward the end, this competition was increasingly

open.

One of the last inspections that Scott Ritter did, he shows up at the

headquarters of Special Security Organization Directorate in downtown Baghdad.

It's a site from which he's been barred before. They've recently been given

permission to go back into Iraq. So he shows up at this site. As he's driving

up, the power-- quote unquote-- fails. Lights go dark. Unexplained power

outage. "Sorry about that, Scott." He goes into the building, using

flashlights through the hallways, and in every office, he finds a clean desk, a

man with a mustache with two or three sharp pencils and two or three empty file

folders, and they ask him, "What do you do here?" And he says, "I register

marriages." This is at the Special Security Organization headquarters in

Baghdad.

And so it was very much in your face by the end. The Iraqis saying, "We know

what you're trying to do and we're never going to let you do it. You're not

going to catch us at it." So "Shake the Tree" is an effort to puncture through

all these walls of deception and cover up. And it goes like this:

There will be a very open effort by UNSCOM inspectors to come upon a sensitive

site. Simultaneous with that, there will be covert efforts to look and listen

to what the Iraqis are doing in response to the UNSCOM approach. Now from the

start, they've synchronized U2 overflights with these inspections. They've

synchronized some other overhead assets like U.S. satellites or signals

aircraft that are operating on the edges of Iraq. This time, they're using

these ground based scanners to listen to Iraqi radio communications.

This is significant because Iraq has no reason to believe that these can be

listened to. First of all, they're encrypted, using the best European

technology that money can buy. Second of all, they're VHF signals, meaning

that they are quite short range, and that means it's very, very hard to hear

them from space or even from aircraft. So, they have good reason to think that

these are secure. UNSCOM, in cooperation with the United States, Israel and

Great Britain, has brought in these scanners which are capable of intercepting

these signals and recording on the digital tape. The tapes are then brought

out and they are stripped, which is the intelligence term for breaking the

code, and they are then translated form the Arabic. And even then, you need to

understand the way Iraqi communications security works.

Even when it's encrypted, they're still speaking in a kind of code. For

example, they would never use the word "missile." Sometimes they would say,

"eagle" when they meant "missile". But, gradually UNSCOM is learning a great

deal about Iraqi concealment methods and who's ordering it and who's running

the organizations. For example, they find out that the people who look like

traffic cops on all the streets where UNSCOM is driving are operating on the

network of the intelligence services, and are being given information and

providing information about UNSCOM's movements in real time. Because one of

UNSCOM's cardinal principles was no advance notice. You would know which site

was being inspected when the inspectors turned up. But you'd know a little

sooner, because you knew which direction they were heading, and the traffic

cops were reporting back and so on. This is perhaps not surprising. But

UNSCOM broke through the mechanism of the concealment in an effort to come up

with a way of catching these hidden caches, either in place or on the open

road. If they ever got to a point where they arrived where the materials were,

and they were under guard, then they would simply be turned away, and then it

becomes a matter for the Security Council.

Every now and then, though, they would catch the Iraqis where the stuff isn't

under guard. There was the case back in '91 where the Army Major managed to

photograph the calutron. There is a case much more recently-- I think it's

September of '97-- when a diminutive female microbiologist from the University

of Florida-- decides to go in the back door instead of the front door of a food

laboratory which she's inspecting, because all those sorts of laboratories are

dubious. And two great big, husky, Iraqi security guards clutching briefcases

literally run into her on their way out the door as she's on her way in. And

she says, "Stop." And they don't know what to do. There's this woman standing

in front of them. And they turn back around and run back inside the building.

And this woman starts running and chasing them. And she catches them. And at

this point I guess they could either shoot her or give her the briefcases, and

they gave her the briefcases.

And this is the kind of thing that "Shake the Tree" was supposed to create:

more and more opportunities like this, in which UNSCOM finally would get its

hands on the hidden stuff.

The famous office safe that was planted at UNSCOM headquarters in Baghdad.

Can you discuss this?

Well I chuckled when I found out that the UNSCOM people had used an office safe

to camouflage their intercepting equipment because that's exactly what I did

when we had to mount an operation in Moscow. We used an office safe to house

all the intercept equipment and also to protect it from radiation which

emanates from all equipment. It's called tempest radiation. An office safe

prevents this radiation so we used it many years ago.

So the reason you use a safe is because the surroundings.. steel cover of

the safe prevents what?

Prevents the unwanted radiation coming from the equipment within that safe

radiating out to perhaps a van which would be sitting on the street close to

the embassy, that's one reason. The other reason is when you've finished your

operation for the day, you slam the door of the safe, you swing the combination

lock and it just looks like an ordinary office safe.

Right. But the shielding is to prevent the buggers being bugged.

Absolutely, that's what it's for. Now you do have to shield the front of the

safe with a copper mesh so the knobs to the receivers and demodulators etc come

through a copper mesh. Again, this thing is completely airtight and 'tempest

proof' they call it.

And you developed this in Canada?

Yes, we did. We did that many years ago and used this in Moscow at our embassy

in Moscow.

What did you call it?

We called it Stephanie. It was a code name given to that operation. Stephanie

was the name of the daughter of one of the chiefs of the organisation I worked

for.

So in Baghdad they actually had a safe in place. Would that then have had

to be adapted?

Yes. Primarily drill some holes in the bottom so you can get some power into

the safe in your antennae cables, that's primarily what you have to do. And

drilling a hole through a safe is not too difficult a task. And then they

would have to protect the front of the safe with copper mesh or something like

that. But if the safe is on site, it's fairly easy to do.

Now open the safe door for me and I see about 5 trays. What are they

doing?

Well you would have one which would be a pre-amplifier which would amplify the

signal as it comes from the antennae. Then you'd go into a de-modulator which

breaks the signal down into a readable form. And if the signal contains two or

more signals on their own, then you would have to de-multiplex it, and then

you.....

What does that mean?

It means to break the two signals apart. You can put two telephone calls, for

instance, on the same line. Well you'd have to de-multiplex it or separate the

two into two separate conversations. And then you would have maybe some other

gismos, a scanner might be in there to pick up active frequencies. You

probably have.. oh maybe a recorder button would be in there too to record the

conversations or whatever it is you're after, and something maybe to change the

analogue to digital form so it would be easy to record, and then maybe compress

it.

Well I want to raise that with you. The bottom tray apparently was the

compressor for all the signals. How would that work?

That compresses it timewise. If the signal is already in a digital form you

just push the digits closer together timewise. So instead of taking 10 micro

seconds to transmit a word it would only take 2 or 3 micro seconds.

The famous burst transmission.

The famous burst transmissions yes.

Now how do you transmit from that office safe? Where would the information

have gone and where would it have finished up and how would it have been

transmitted?

It would have been transmitted from the office safe to a location safe but

outside the borders of Iraq. In this case I believe it's Bahrain. It would be

transmitted there by low power microwave signal - very, very low power - in a

burst transmission so very difficult for the Iraqis to intercept that.

Where's the transmitter?

It would be in the safe also. A very, very small low powered transmitter,

right within the safe, and the antennae used to intercept the signals would be

used also to transmit the burst transmission out.

But if the safe is shielded from interception, how can it then transmit

out?

Oh it goes by a coaxial cable through the holes in the bottom of the safe to

the transmitter which is probably concealed in the form of a video camera or an

air vent or something on the roof of the building or close to it.

In fact we're told there was a video camera on the roof disguised as an

aerial.

Common practice used by the Special Collection Service to hide

antennas.

So that's both receiving and transmitting?

Can be used for either one, yes, and usually is.

I'm told that there was something that identified key words so that not too

much material was transmitted to Bahrain. What would that have been and how

does it work?

Well I am familiar with the system called Oratory which was developed by the

NSA to filter out the unwanted conversations on transmissions. You feed into

Oratory the words that you want the intercept on, such as Saddam Hussein, such

as Inspectors, such as anthrax, whatever you wish. You feed these words into

this computer and tell the computer you want all conversations or

communications containing these words. The other end of the computer you feed

in all the intercept that you get, and coming out of Oratory would be the

intercepts that you asked for containing these words.

Where is Oratory and what does it look like?

The Oratory that I was familiar with was about the size of a bread box. Now

I'm sure today they've reduced this down to the size of a package of American

cigarettes or even smaller.

Would that have been in the safe?

Yes, that would have been in the safe also unless it in itself is tempest

proof. Now the Oratory that I worked with was tempest proof so you could leave

it out - but not necessarily so.

So the signal then goes from UNSCOM headquarters in Baghdad to Bahrain, and

it's received by what?

Would be received by a normal dish antennae, it would receive that, Bahrain,

in that form, and maybe broken down for some real time analysis and real time

intelligence reporting.

If you're getting real time reporting, logically that information would go

to the nearest base we know of which would be Royal Airforce, Akrotiri in

Cyprus.

That's a logical place to send it, yes.

But we know some of the signals went to Fort Mead.

Yes.

So again, how would that be transmitted and what happens when the

information gets to Fort Mead?

If the information received at Bahrain is in an analogue form it would be

changed to a digital form. It would be multiplexed together. You'd have more

than one transmission and in this case I believe it's five. You'd put these

five transmissions together in a digital form, then you would multiplex, in

other words mix them all up. So you'd have five conversations mixed up

digitally. Then they would be compressed into a very small time frame, then

encrypted and then relayed via satellite from Bahrain to NSA at Fort Mead or

the Special Collection Service at Belsville Maryland, and at that location they

would do the opposite. They would decrypt it, decompress it, de-multiplex it,

get the plain language and do a long-term analysis.

Now we're told that a substantial amount of the signals that came in were

garbage. Is that the usual...

Always the case. Yes, that is most usual. I would say 99.9% of the

material intercepted in any one location is garbage and goes to ground. But

that .1% that you get is a gem, it's the Hope diamond.

It will be denied.. it will be formally denied that the process that you've

just talked about took place.

Of course. Of course it would be formally denied.

Why?

Well I don't think anyone in that business would get up and say yes we are

doing this. The plausible deniability is so easy and done by all countries

that participate in this.

How would equipment have been brought into Baghdad?

Baghdad historically is a very difficult capital city to get the equipment

into. It is known that they X-ray all diplomatic bags coming into Baghdad and

going out of Baghdad. Very, very difficult to get equipment in. I do know

that in the early days when I was involved in an operation the Americans were

not very welcome in Baghdad but the British were somewhat more welcome. So the

British were able to bring into Baghdad receivers, demodulators,

de-multiplexers, literally piece by piece, knob by knob, in diplomatic bags,

that is the normal way.

But if the bags were X-rayed, why weren't these things discovered?

Because they were normally wrapped in tin foil and then put into a tin box

of some sort and concealed. So when the bag is X-rayed, all that will show up

is just a square box of something.

So your best bet on that one, how Stephanie was smuggled into

Baghdad?

Well Stephanie was definitely smuggled into Moscow that way, but the British

into Baghdad would have been going by diplomatic bag. It's the normal way to

send equipment.

Can I ask you about some of the eavesdropping and bugging equipment - I

suppose it's the same really - that according to Ritter was left in Baghdad and

was used. What are we talking about here?

Well we could be talking about a number of different types of equipment,

probably some stuff that was bought at the local radio shack and modified for

that purpose, probably some stuff that was developed by the Special Collection

Service at Belsville, Maryland, probably some stuff that they could probably

obtain right on the open market in Baghdad and modified for their own

use.

What kind of bugging equipment would we not expect to see?

Very little. I would think in Baghdad just about every type of bugging

equipment that has been used by the NSA or the GCHQ was probably in use

then.

No, but what did you use that was really unusual?

We used listening devices, in Moscow and other places, to intercept

conversations of the leaders of that country that we used that type of

equipment.

But what did the bugs look like?

Oh the bugs looked... we never used bugging of rooms, we didn't use that

type of bugging at the organisation I worked for. Again, the RC impeded that

sort of thing. But when I was in the business, bugs were quite big and

difficult to conceal, and I know nowadays they're very small and very difficult

to find.

I want you here really to talk about pigeons and twigs and roses and so

on.

I didn't know you're into that because they're not bugs, those are

intercept.

What about intercept devices?

Well I do know that the Special Collection Service was able to have some

very sophisticated and funny intercept devices. An example would be right in

Washington DC. The Soviet Embassy there was a very difficult embassy to plant

a bug in an office, but one of the engineers at NSA decided to catch a pigeon

which always sat on a ledge of the window of this office and bug the pigeon.

So the pigeon actually contained a little receiver and a little transmitter and

a little antenna, and as it sat on the window ledge of this office it picked up

the conversations within that office and transmitted them to an NSA van just

down the street.

And it worked?

It worked very, very well. Typical NSA fashion, after the operation was

over they caught the pigeon, removed the bug, but stuffed it as a memento and

it sits there at NSA as the prize.

Any other devices like that for...

Tree branches commonly used also at the embassy in Washington again, the

Chinese Embassy. It was known that the Ambassador would not hold classified

conversations in his office because he thought that his office was bugged,

which in fact it was, but he did go outside and sit on a garden bench on a

regular basis and talk to his senior advisors on presumably classified matters.

So again the NSA got a tree branch, fashioned one similar to it out of fibre

glass and then planted the bug inside this tree branch. On a very windy night

in Washington DC the branch was thrown over the fence of the Embassy and it sat

right underneath the bench where the Ambassador held his conversations, and

again it transmitted these conversations to a van down the street.

home +

experts' analyses +

photos +

interviews +

what it took +

join the discussion

readings & links +

chronology +

synopsis +

tapes & transcripts

frontline +

pbs online +

wgbh

web site copyright WGBH educational foundation

|