|  |

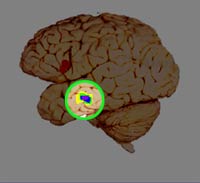

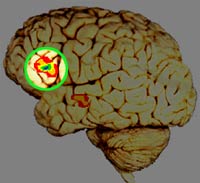

| Teens (left) used less of the prefrontal (upper) region than adults (right) when reading emotion. |

This is a really nice picture highlighting the fact that in an adolescent brain

or a younger brain, the relative activation of the prefrontal region or this

anterior front part of the brain is less it is in the adults. But in contrast

to that, the more emotional region or that gut response region has more

activation compared to the adult. So the relationship between these two regions

is very different. And we think that that's been a very important finding in

terms of understanding adolescent behavior.

So, confronted with a feeling, say, somebody looks at them with an

expression of fear, how will the adolescent read it in relation to the

adult?

... The adolescent will have a more of an emotional response. The part of the

brain that has more of that gut reaction will respond to a greater extent than

the adult brain will. And we think that that is due to the fact that this

frontal region is not interacting with the emotional region in the same way.

How about this issue of misjudgment -- making mistakes about what they read

on a person's face?

One of the things that we noticed in doing this experiment was, not only did

the adolescents show this emotional response or this increased response, but

they did this at the same time that they did not correctly identify the

emotion. And that was very interesting to us, because it's clear that the brain

was responding, but the way it was responding didn't have to do with the

accuracy of the affect or the emotional expression. The adolescents typically

said that they saw shock or confusion or sadness. But they did not correctly

identify fear 100 percent of the time. This is in contrast to the adults, who

did find that.

So 100 percent of the adults correctly identified the emotion of

fear?

Right. In this pilot study, 100 percent of the adults did actually identify the

emotion as fear.

And the teenagers?

Only about half.

What did they say instead?

They felt that the expression was sadness, confusion. Some said they didn't

know; some said shock. But it was surprising to us that most fairly

sophisticated adolescents did not correctly identify fear. ...

Is it possible that if you had interviewed ten more adults and ten more

teens, the results would have changed?

This is a small pilot study, so clearly if we added a considerably larger

sample, we may have very different results. So I want to be cautious and not

over-interpret these findings.

What does your work tell you about young teenagers?

One of the implications of this work is that the brain is responding

differently to the outside world in teenagers compared to adults. And in

particular, with emotional information, the teenager's brain may be responding

with more of a gut reaction than an executive or more thinking kind of

response. And if that's the case, then one of the things that you expect is

that you'll have more of an impulsive behavioral response, instead of a

necessarily thoughtful or measured kind of response.

Does this research go part of the way to explaining the miscues between

adult and teenagers?

Yes, I do think this research goes to helping understand differences between

adults and teenagers in terms of communications. And I think that it does for

two reasons. One, we saw that adults can actually look at fearful faces and

perceive them as fearful faces, and they label them as such, whereas teenagers

... don't label them the same way. So it means that they're reading external

visual cues [differently], or they're looking at affect differently.

The second aspect of the findings are that the frontal region, or this

executive region, is activating differentially in the teenagers compared to

adults. And I think that has important implications in terms of modulating

their own responses, or trying to inhibit their own gut responses.

Talk more about that in terms of the kind of risks that teenagers take. When

they exhibit risky behavior, what is actually happening?

One thing that happens in the brain when we're going to get involved in any

activity or initiate any activity is, we either have to decide what the

consequences of that behavior are, or we're just going to behave impulsively.

And to appreciate what the consequences of a behavior are, you have to really

think through what the potential outcomes of a behavior are. I think the

frontal lobe, that part of the executive region that we studied, is not always

functioning fully in teenagers; or least our data suggests that perhaps it's

not.

That would suggest that therefore teenagers aren't thinking through what the

consequences of their behaviors are, which would lead us to believe that they'd

be more impulsive, because they're not going to be so worried about whether or

not what they're doing has a negative consequence. ...

Our findings suggest that what is coming into the brain, how it's being

organized, and then ultimately the response -- all three of those may be

different in our adolescents. So that attitude may be part of that, or may be

related to that. But it's not simply a matter of teenagers feeling like they

don't want to do something, or that they're just going to give you a hard time.

...

What does this mean for teens' relationship with their parents and

teachers?

One of the interesting things about the findings are that they suggest that the

teenagers are not able to correctly read all the feelings in the adult face. So

that would suggest to us that when they're relating to their parents or to

their friends' parents or to their teachers, they may be misperceiving or

misunderstanding some of the feelings that we have as adults; that is, they see

anger when there isn't anger, or sadness when there isn't sadness. And if

that's the case, then clearly their own behavior is not going to match that of

the adult. So you'll see miscommunication, both in terms of what they think the

adult is feeling, but also what the response should then be to that.

Is there a difference between boys and girls?

Yes. Actually it's very interesting that in our study we found quite a bit of

difference between males and females. And this really didn't surprise us. We

found that females were somewhat more accurate than males, and also a little

bit more subdued, relative to males. ... In general, the males in our studies

showed more reaction from that gut region of the brain, and less frontal or

executive reaction. The relationship between the gut response and that

executive region was very striking for the males, and somewhat striking for the

females, but was not as extreme for the teenage females compared to the teenage

males. ....

So what does this mean about the kind of decisions that a teenager

makes?

One of the interesting outcomes of this study suggests that perhaps decision-making in teenagers is not what we thought. That is, they may not be as mature

as we had originally thought. Just because they're physically mature, they may

not appreciate the consequences or weigh information the same way as adults do.

So we may be mistaken if we think that [although] somebody looks physically

mature, their brain may in fact not be mature, and not weigh in the same way.

...

Certainly the data from this study would suggest that one of the things that

teenagers seem to do is to respond more strongly with gut response than they do

with evaluating the consequences of what they're doing. This would result in a

more impulsive, more gut-oriented response in terms of behavior, so that they

would be different than adults. They would be more spontaneous, and less

inhibited. ...

Do you think there should be things done for teenagers that are not done

right now?

That's a really interesting point, because enrichment or special kinds of

education during this period of time are very valuable; the brain is ready and

responsive in a way that it's not later in life. And one of the questions is

whether or not we can teach teenagers or adolescents to be more discriminating

in interpersonal communication.

For example, many adults say that one of the things that they felt most limited

by is the ability to have a really good relationship, a really intimate

relationship with another person. And the basis of that really comes out of

being able to read cues and being able to relate to others. So I think that the

teenage years are important years for learning those skills. We assume that

teenagers are getting those skills at home, or we think that they're getting

them in groups that they participate in, such as Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, clubs

that they belong to. But for perhaps many of our teens, they're not getting

these skills, and maybe we've just assumed they're getting them. ...

... Have the results of your work, and that of others studying adolescents

changed you in your own dealings with teenagers?

Oh yes. I think that I also came to this research with the assumption that the

teenager was going to look a lot like an adult. In fact, I assumed that the

year-old brain would respond quite similarly to the adult brain in terms of the

kinds of tasks that we were asking them to do when they were in the magnet. So

I was quite surprised when we initially got these responses and found that

there seemed to be a different pattern. And I was very reassured when other

investigators such as Dr. Giedd had indicated that their findings also

suggested ongoing structural changes in the brain. Of course, it makes sense

that the behavior would be different through adolescence, in retrospect. But I

was surprised. ...

What can your research tell parents?

One of the things I think that this research could help inform us about is the

fact that the teenager is not going to take the information that is in the

outside world, and organize it and understand it the same way we do. That's a

very general statement. But when you think about it in terms of interactions at

the dinner table or on the weekend or doing chores or doing homework, it means

that whatever communication, whatever conversation you have with them, if

you're assuming they understood everything you said -- they may not have. Or

they may have understood it differently.

And if you think that their assignments are clear to them, they may not be. So

it may be that we're putting them in a difficult situation, because we're

assuming that our conversation is very clear, when in fact they may also think

they've understood it clearly; but we're not saying the same things to each

other.

... A good example of that is the typical Saturday morning conversation where

there is a number of small things that a child or adolescent would be told to

do. "Put your dish in the sink. Please get dressed now. We're going to get

ready to go out." And ten minutes later, there seems to be no movement, the

dish is not in the sink and they're not dressed. And the first response as an

adult is that they're being difficult or confrontational or not wanting to do

it.

But in fact, a lot of the time they're just not paying attention; either they

heard that information, but they didn't really register it, or they heard it

and they thought it was OK to do it later. Or they heard it, but whatever came

on TV seemed more important. They somehow have reorganized that information, so

they're not really trying to disappoint you or frustrate you. It's just that

they saw it in a different light. ...

home + introduction + from zzzs to a's + work in progress + seem like aliens? + science

discussion + producer's chat + interviews + video excerpt + watch online

tapes & transcripts + press reaction + credits + privacy policy

FRONTLINE + wgbh + pbs online

some photographs copyright ©2002 photodisc. all rights reserved

web site copyright WGBH educational foundation

|