The Jewish Diaspora

Jewish communities, spread thoughout the Empire, became vehicles to spread the 'good news' of Jesus Christ.Professor of Classics and Director of the Religious Studies Program University of Texas at Austin

The Diaspora

When we see the Christians beginning to spread out beyond the original homeland environment, they're following a pathway that had already been well trod before them by other Jews. By the middle of the first century, there are probably more Jews living outside of the homeland, than actually live back in Judah proper. This is what we call the Diaspora, that is, the dispersion of Jewish population throughout the Empire, and we know that there are major Jewish communities in most of the large cities of the Empire, all the way from the Persian Gulf on the east to Spain on the west. It's an extensive diffusion of the Jewish population throughout the Roman.

So, what was the relationship like between Jews and [these other communities where they found themselves?]

And these these Jewish communities in the Diaspora environment faced a number of challenges. How do you maintain your traditional Jewish identity and piety, while at the same time fitting into the social and cultural traditions of Greek and Roman cities? In some localities, we find Jews participating in the theater or in normal aspects of daily life. In other cities, we find Jews experienc[ing] oppression and seeming to distance themselves from the local environment. So, it varies from city to city, on what the Jewish experience would be. On the whole, however, Judaism in the Diaspora was able to accommodate a great deal of Hellenistic culture. The normal language for Jews in the Diaspora was Greek. It was in the Diaspora that the Bible was translated from Hebrew into a Greek vernacular. So, later on, when we find Paul quoting scripture, he's not quoting the Hebrew Bible. He may not even know the Hebrew Bible directly. He quotes the Bible in Greek.

JEWISH POPULATION IN ROME AND OSTIA

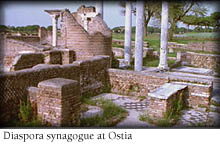

There are very large Jewish communities in some of the major Roman cities. Rome itself, seems to have something on the order of ten different synagogue congregations, and the Jewish population of the city of Rome at its zenith was perhaps 100,000. Unfortunately, we have no archaeological evidence of the actual synagogue buildings themselves from the city of Rome but fortunately, a recent archaeological discovery from the nearby port city of Ostia, shows us one such congregation, in its very real setting.

When you go through the city of Ostia, you're seeing a kind of microcosm of the city of Rome, in the first century. It's a little Rome, and as you go down the main streets of Ostia, and you go out the gate near the harbor, down the road, you find a little building just off to the side, and as you go in, you find a hall for assembly. From the outside, this building looks like any other along that street. You wouldn't know it's ... a place of worship for a Jewish community until you go inside and look at the carvings over the the arches that show us a menorah. This is a Jewish synagogue. It may date from the very end of the first century and is one of the earliest that we know of, from the Diaspora.

So, here's a Jewish congregation through several generations trying to maintain its its life, its identity, in a major Roman city. It's interesting that ... right adjacent to the hall of assembly, is a kitchen and a dining room. Apparently, they too had fellowship dinners. Apparently, they too were engaged in an active social life.

JEWISH CATACOMBS IN ROME

One of our best sources of information about the Jewish community at Rome comes from their burial places. There are several important Jewish catacombs, and they've yielded hundreds of inscriptions that tell us the names and identity of the the numbers of the Jewish congregations in Rome. They're a mixed lot. Some of them seem to be predominantly Aramaic speaking, and don't know much Greek, but the vast majority used Greek and a few even know Latin. What they show us is how thoroughly integrated the Jewish communities were in the social life of Rome. They participate in all aspects of commerce and trade. They are busy organizing their community life. We hear of people who are the mothers or fathers of the synagogues, meaning they're the ones who actually build the buildings and support the congregations. We hear of the leadership of the Jewish groups. So, we find these Jewish communities really trying to maintain their identity, just like any immigrant group would have expected to do in their new locality.

Samuel Ungerleider Professor of Judaic Studies and Professor of Religious Studies Brown UniversityThe Greek word "diaspora" means a scattering. And indeed there was a scattering of Jews throughout the known Greek and Roman world from the third century B.C. and on down. There's a famous utterance by Strabo, a Greek geographer of the late first century, B.C., who says that you can't go anywhere in the civilized world without encountering a Jew. And by his time this certainly was true. There were large Jewish communities in Egypt, especially in Alexandria, but even throughout the countryside, up the Nile Valley. There were large Jewish communities in Syria, a very large one in the city of Antioch, but throughout Syria, and there were numerous Jewish communities throughout Asia Minor, modern day Turkey, just as there were Jewish communities in Greece and throughout the Italian peninsula, most especially of course in the city of Rome. Even further west, we know about Jews in southern France, and Jews in Marseilles and perhaps even Jews in Spain....

It's interesting to note that early Christianity first spread in those areas where there was a Jewish presence. That is, it spreads in Egypt, it spreads in Syria, it spreads in Asia Minor, it spreads in Greece and Italy. These are precisely areas where we know there were Jewish communities, there were Jewish synagogues and there were Jews in number scattered throughout all these areas. Presumably the earliest Christian travellers and missionaries like Paul would begin their travels by obviously approaching their brethren, approaching their fellow Jews, and converting some of them to the new path or the new religion, if I may use that word, or the new way of thinking, and perhaps using these communities as springboards from which to get access to the non-Jews in these very areas also. It's clear, then, that the Diaspora communities formed the Jewish network which early Christians as Jews were able to use for their own purposes.

SYNAGOGUES IN THE JEWISH DIASPORA

The word "synagogue" is a Greek word, it means a gathering or an assembly, or perhaps a congregation. The synagogue, then, was the point of communal organization of the Jews in the Diaspora. Wherever you have a sufficient number of Jews, you would have a Jewish community. Wherever you would have a Jewish community you would have a Jewish synagogue. The synagogue, then in part, is a community building or a community place, a place where Jews would gather to discuss matters of communal concern. Sort of like a New England town square, where the citizens would gather regularly to discuss issues of importance. Among the issues that they would discuss, of course, Jews would discuss Judaism. That is to say they would discuss their sacred texts. Many of our sources tell us that Jews would gather in synagogues regularly, perhaps every Saturday on the Sabbath, or perhaps more often than that, in order to read the laws, to read the Torah, the sacred book of Moses and to expound upon it. And any reader of the New Testament knows that this is what Jesus did in the homeland, in the Galilee, entering the synagogues on the Sabbath and expounding the scriptures. And of course, we also know this from Paul, that in his travels in Asia Minor, Paul routinely went to seek out the local synagogue and therein to teach the scriptures from his peculiar perspective, but teach the scriptures to the Jewish community. So something else that happens there in a synagogue then in these public gatherings will be the communal study of the sacred texts, specifically of the Torah. We imagine also that they probably will have prayed, together....

According to the New Testament, another remarkable feature of the synagogues in the Diaspora is not only that they attracted large crowds of people, but among these crowds will have been gentiles. Gentiles apparently found these synagogues to be interesting or a place worth visiting, perhaps because they enjoyed hearing the philosophical type discussions about God, or perhaps they enjoyed hearing things being sung or chanted. We don't know exactly why gentiles found these places attractive; modern scholars too readily assume it's because these people were somehow believers of Judaism, or somehow were half converts... as if there's no other rational explanation why gentiles would want to go to a synagogue if they were not almost converting to Judaism. But the fact is there are many reasons why gentiles may have come.... Gentiles found the Jewish synagogues and the Jews themselves apparently open, interesting, attractive, friendly and why not go to the Jewish synagogue, especially because there are no non-Jewish analogs. There's nothing equivalent to this communal experience anywhere in pagan or Greek or Roman religions. And we shouldn't be surprised if it would have attracted curious, well intentioned by-standers, who may have come in to witness, or perhaps even participate to some degree in what was going on.

William Goodwin Aurelio Professor of the Appreciation of Scripture, Boston University

JEWISH IDENTITY AND THE DIASPORA

The Jewish way of constructing reality is through the Bible. And the center of gravity in the Jewish Bible, what pulls the story along, is getting to the land of Israel. So the land of Israel, the promise of land to Abraham, the importance of the land, the holiness that goes along with the land, is embedded in Jewish historical imagination through the medium of the Bible. This means that religiously and socially, any place outside the land is, in a sense, not home for a Jew, even if Jews can live for generations in other cities.

The Jewish way of constructing reality is through the Bible. And the center of gravity in the Jewish Bible, what pulls the story along, is getting to the land of Israel. So the land of Israel, the promise of land to Abraham, the importance of the land, the holiness that goes along with the land, is embedded in Jewish historical imagination through the medium of the Bible. This means that religiously and socially, any place outside the land is, in a sense, not home for a Jew, even if Jews can live for generations in other cities.

The Jewish designation... for territory other than the land of Israel, is the Diaspora. And by the time of the first century, there were probably then, as now, more Jews living outside the land of Israel than within the land of Israel. There's a very energetic Jewish population in Babylon since the destruction of the first temple. There is a very wealthy, vigorous Jewish population living in the major cities around the Mediterranean. And that population, which is speaking Greek, which is the matrix of the Greek translation of the Jewish Bible, which becomes eventually the seedbed of Christianity ... to make the idea of Israel available to Greek readers ... to liberate it, in a sense, from its native language.

Nonetheless, despite the wide dispersion of Jewish population throughout the Roman Empire and in the east, Jews are bound together imaginatively and socially by the calendar. Jews have this trans-local imaginative community. They have every seventh day off ... they're the ones who have the weekend in antiquity. They have the Sabbath, which is a time, typically, for the community to gather wherever it is, whether they're in a village in the Galilee, or in a suburb of Rome, and hear the law read... they have the great pilgrimage holidays. They have the calendar of the Jewish liturgical year. And therefore, Jewish populations in the Diaspora would also journey home even if their actual home was Alexandria or Rome or any place in Asia Minor. Their spiritual home and their historical home was Israel, and specifically, Jerusalem.