From Hebrew Bible to Christian Bible: Jews, Christians and the Word of God

In his teaching, Jesus often quoted the Jewish Scriptures; after his death, his followers turned to them for clues to the meaning of his life and message. Biblical scholar Mark Hamilton discusses the history of these ancient texts and their significance for early Christians and their Jewish contemporaries.Mark Hamilton is currently writing a PhD dissertation at Harvard University called 'The Body Royal: Kingship and Masculinity in Ancient Israel.' His article "The Past as Destiny" will appear in the October issue of the Harvard Theological Review

The Origins of the Hebrew Bible and Its Components

The Origins of the Hebrew Bible and Its Components

The sacred books that make up the anthology modern scholars call the Hebrew Bible - and Christians call the Old Testament - developed over roughly a millennium; the oldest texts appear to come from the eleventh or tenth centuries BCE. War songs such as Exodus 15 and Judges 5 are very archaic Hebrew and celebrate Israelite victories from the time preceding the Israelite monarchy under David and Solomon. However, most of the other biblical texts are somewhat later. And they are edited works, collections of various sources intricately and artistically woven together.

The five books of Pentateuch (Genesis-Deuteronomy), for example, traditionally are ascribed to Moses. But by the eighteenth century, many European scholars noticed problems with that assumption. Not only does Deuteronomy end with an account of Moses' death (a tough assignment for any writer to describe his or her own demise), but the entire Pentateuch shows anomalies of style that are hard to explain if only one author is involved.

By the nineteenth century, most scholars agreed that the Pentateuch consisted of four sources woven together. This notion of four sources came to be known as the Documentary Hypothesis, and, in various forms, it has been the prevailing theory for the past two hundred years. Israel thus created four independent strains of literature about its own origins, all drawing on oral tradition in varying degrees, and each developed over time. They were combined together to form our Pentateuch sometime in the sixth century BCE.

By this time, many of the other biblical books were coming together. Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings form what scholars call a "Deuteronomistic History" (because the work's theology is heavily influenced by Deuteronomy), a history of the Israelite states over a five-hundred-year period. This work contains much of historical value, but it also operates on the basis of a historical and theological theory: i.e., that God has given Israel its land, that Israel periodically sins, suffers punishment, repents, and then is rescued from foreign invasion. This cycle of sin and redemption shapes the work's way of writing history and gives it a powerful religious dimension, so that even when the sources behind the biblical books are "secular" accounts in which God is far in the background, the theology of the overall work places history in the service of theology. The last edition of the Deuteronomistic History, the one in our Bible, comes from the sixth century BCE, the time of the Babylonian Exile. In this context, it offers an explanation for Israel's poor condition and implicitly a reason to hope for the future.

Another section of the Hebrew Bible consists of the prophets (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, the twelve "minor," i.e., brief, prophets). Here again, it's important to understand how these developed. In the book of Isaiah, from which Jesus quotes, the original Isaiah of Jerusalem lived in the eighth century BCE in Jerusalem, and much of Isa 6-10 clearly reflects the political and social events of his time. Another part of the book, however, comes from a prophet who lived two hundred years later: Isaiah 40-55, famous in the New Testament (early Christians thought the suffering servant of Isaiah 53 was Jesus) and prominent in Handel's Messiah, speaks of the Persian king Cyrus the Great (d. 530 BCE), and so the text must come from that time. Other parts of the book of Isaiah are even later, and the entire book was carefully edited together, perhaps by the fifth or fourth century BCE. The extraordinary poetry of the book offers the reader hope in a God who controls historical events and seeks to return his people Israel to their own land.

In addition to the prophets, the Hebrew Bible contains what Jews often call the "Writings," or the Hagiographa, hymns and philosophical discourses, love poems and charming tales. These include Psalms, Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes (or Qoheleth), Song of Songs, Esther, Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah, and Chronicles. These books were the last completed and the last to be received as Scripture, although parts of them may be very ancient indeed. The books of Psalms, for instance, contains many hymns from Israelite temple worship from the monarchic period, i.e., before the Babylonian Exile in the sixth century BCE; songs such as Psalm 29 may be borrowed from the Canaanites, while Psalm 104 closely resembles Egyptian hymns. In its current form, the 150 psalms fall into five "books," modeled on the five books of the Pentateuch.

Proverbs also has many old parts, including one apparently translated from the second-millennium BCE Egyptian text the "Instructions of Amenemope" (Proverbs 22). The remaining books in this part of the Bible are somewhat later: the latest is probably Daniel, which comes from the mid-second century.

From Many Books to the One Book

How did these various pieces come to be regarded as Scripture by Jewish and, later, Christian communities? There were no committees that sat down to decree what was or was not a holy book. To some degree, the process of Scripture-making, or canonization as it is often called (from the Greek word kanon, a "measuring rod"), involved a process, no longer completely understood, by which the Jewish community decided which works reflected most clearly its vision of God. The antiquity, real or imagined, of many of the books was clearly a factor, and this is why Psalms was eventually attributed to David, and Proverbs, Song of Songs, and Ecclesiastes (along with, by some people, Wisdom of Solomon in the Apocrypha) to Solomon. However, mere age was not enough. There had to be some way in which the Jewish community could identify its own religious experiences in the sacred books.

This occurred, at least in part, through an elaborate process of biblical interpretation. Simply reading a text involves interpretation. Interpretative choices are made even in picking up today's newspaper; one must know the literary conventions that distinguish a news report, for example, from an op-ed piece. The challenge becomes much more intense when one reads highly artistic texts from a different time and place, such as the Bible.

The earliest examples of interpretation we have appear in the Bible itself. Zechariah reinterprets Ezekiel, Jeremiah often refers to Hosea and Micah, and Chronicles substantially rewrites Kings. These reinterpretations are in themselves evidence that the older books were already becoming authoritative, canonical, even as the younger ones were still being written.

But some of the oldest extensive reinterpretations of our Bible come from the third or second centuries BCE. For example, the book of Jubilees is a rewriting of Genesis, now arranged in 50-year periods ending in a year of jubilee, or a time for forgiveness of debts. A related work is the Genesis Apocryphon, also a rewriting of Genesis. Ezekiel the Tragedian wrote a play in Greek based on the life of Moses. And the Essenes, the sect that produced the Dead Sea Scrolls, composed commentaries (peshers) on various biblical books: fragments of those on Habakkuk, Hosea, and Psalms survive. From the first century BCE or so, come additional psalms attributed to David and the Letter of Aristeas (about the miraculous translating of the Bible into Greek), among others. And during the life of Jesus himself, Philo of Alexandria wrote extensive allegorical commentaries on the Pentateuch, all with a view toward making the Bible respectable to philosophers influenced by Plato.

Despite their great variety of outlook and interests, all of these works shared certain common views. They all believed the author of the Bible was God, that it was therefore a perfect book, that it had strong moral agendas and that it was abidingly relevant. Interpretation had to show how it was relevant to changing situations. They also thought the Bible to be cryptic, a puzzle requiring piecing together. The mental gymnastics required to make the old texts ever new is one of the great contributions of this era to the history of Judaism and Christianity, and therefore Western civilization itself.

An example of interpretation: Genesis 11

Genesis 11 is the story of how humans soon after the Flood built a city centered around a tower "with its top in the heavens." The purpose of the Tower of Babel was to allow its builders to "make a name" for themselves. God, in a pique of anger, alters the builders' languages so that they cannot understand each other. In its original form, the story is an explanation of why not everyone speaks Hebrew, as well as a comment on the huge temple-towers (ziggurats) of Mesopotamian cities.

For later interpreters, however, this story cried out for explanation. Why was God afraid of these people? How high was the tower? Who led the construction, and did anyone voice objections? What did the builders expect to do when they reached the heavens? What moral lessons should one learn from the story?

To answer these questions and others, Jubilees 10 says that the builders worked for 43 years (50 years of the Jubilee period minus the mystical number seven) and built a structure one and a half miles high! Their purpose was to enter into heaven itself. Pseudo-Philo's Biblical Antiquities (first century CE) adds a story about Abraham, a model of courage, refusing to cooperate with the builders and so being thrown into a fiery furnace, much like the three young men in Daniel 3. God sends an earthquake to destroy the furnace, and then he changes both the builders' languages and their appearance, so that no one can recognize even his or her own brother. Other traditions think that the builders of the tower were either giants (Pseudo-Eupolemus), or were humans led by the mighty hunter and city-builder Nimrod mentioned in Genesis 10 (Josephus). Each interpreter imaginatively builds on some chance word or phrase in the biblical text to try to answer reasonable questions about it. Meanwhile, the first-century philosopher and biblical interpreter writes an entire book on this chapter, which he interprets as an allegory about human morality: the builders represent greed and venality.

The Book and the Once and Coming Messiah

Like their Jewish predecessors and Jewish contemporaries, early Christians believed that the Hebrew Bible was God's book, and therefore a book that should cast light on current events and moral conundrums. For Christians, of course, the most important issue was the true import of Jesus and the story of his life, death, and resurrection. Since they believed him to be the messiah ("anointed one"), God's savior and the harbinger of a new and perfect age, they sought to find mention of him in the Hebrew Bible itself. This is why so much of the story of Jesus in the gospels quotes the Bible.

This move was not without precedent. The Dead Sea community also believed that the prophets had predicted their movement and their leader, the Teacher of Righteousness, as well as the political events of their time. They go so far as to claim that the prophets did not know what they were saying, but God, the true author of the text, used them to speak of the (to them) distant future.

Christians, however, had a different set of questions than the Dead Sea sect, and so they found different texts to cite. Any texts that refer to a time of a future deliverance, or the coming of a future king, were fair game. So the suffering servant of Isaiah 53 becomes the suffering Jesus of the gospels. And Luke's quotation from Isaiah 61 becomes a reference to Jesus's ministry of healing and reconciliation. Yet in every case, as far as we can tell, the Christian reading comes after the fact. That is, they first believed in Jesus and then tried to find his life in Scripture. They then could shape their telling of stories about his life to fit the scriptures. This process may seem very circular, but given their assumptions -- namely, that Jesus is central to God's plan, that God spoke through prophets who might not understand their own words, and that the Bible was a cryptic puzzle needing solving -- this belief in prophecy and fulfillment is not incomprehensible. So Luke can have Jesus say, "Today this Scripture is fulfilled in your presence!" Jesus saw himself as the deliverer that the prophets had foreseen long before. When his followers drew the same conclusion, they could then retain the ancient Scriptures, transforming them into something new, a Christian Bible.

Bible Etymology

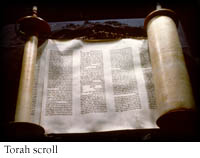

The English word "Bible" is from the Greek phrase ta biblia, "the books," an expression Hellenistic Jews used to describe their sacred books several centuries before the time of Jesus. Christians adopted the phrase "Old Testament" to refer to these sacred books they shared with Jews.

Jews called the same books Miqra, "Scripture," or the Tanakh, an acronym for the three divisions of the Hebrew Bible: Torah ("instructions" or less accurately "the law"), Neviim ("prophets"), and Kethuvim ("writings," including Psalms, Proverbs, and several other books). Modern scholars often use the term "Hebrew Bible" to avoid the confessional terms Old Testament and Tanakh.

As for the New Testament, its current twenty-seven book form derives from the fourth century CE, even though the constituent parts come from the first century. Christians did not agree on the exact extent of the New Testament for several centuries.

For Further Reading

Brueggemann, Walter. Theology of the Old Testament: Testimony, Dispute, Advocacy. (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1997).

Charlesworth, James H., ed. The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. (2 vols.; Garden City: Doubleday, 1985).

Kugel, James. The Bible as It Was. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997).

Idem. In Potiphar's House: The Interpretive Life of Biblical Texts. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990).

Leiman, Sid. The Canonization of Hebrew Scripture. (Hamden, CT: Archon, 1976).

Levenson, Jon. Sinai and Zion: An Entry into the Jewish Bible. (San Francisco: HarperSan Francisco, 1985).

Noth, Martin. A History of Pentateuchal Traditions. (1948; trans. by Bernhard Anderson; Atlanta: Scholars, 1981).

Vermes, Geza, ed. The Dead Sea Scrolls in English. (3d ed.; New York: Penguin, 1987).