|

How did you first get to know Bill Clinton?

I first met him in 1972, when we were both working for George McGovern's

presidential campaign. I was traveling around on the plane with Senator

McGovern, writing speeches. Bill Clinton was running the state of Texas. I

remember landing for a rally at San Antonio, and this rather tall, young fellow

with a white sort of southern suit came bounding up the plane to escort Senator

McGovern down to the rally. So I met him back then.

But I really got to know him much more closely in the 1980s. He was then

governor. He came to Washington frequently to testify or for National

Governors Associations meetings, and we would spend time together. I tried

then to convince him to run for president in 1988. . . . He was almost

convinced, but then he decided not to run in 1988. But again, in 1991, when he

decided to run, I told him I would do what I can to help him.

You were his chief foreign policy advisor during the campaign in 1991-1992.

In that campaign, then-Governor Clinton focused on domestic policy, the

economy, the deficit. He didn't spend a lot of time on foreign policy. Back

then, was he someone who was going to relegate foreign policy to the back

burner?

No, I don't think so. Don't forget that he had graduated from the

School of Foreign Service at Georgetown. He had studied abroad. He obviously

knows the world quite well, and traveled widely, even as a governor. Obviously,

the campaign in 1992 was "about the economy, stupid," as we were reminded

periodically by Mr. Carville. But we actually talked a bit about foreign

policy in 1992 in the campaign. The objective there was to make clear that

Governor Clinton could handle foreign policy. We talked about Russia. We

talked about Bosnia. We talked about Haiti. And in some cases, really we're

out in front of incumbent President George Bush, who obviously was well

regarded in foreign policy. I don't believe that Governor Clinton lost any

votes because of foreign policy back in 1992. That was my job -- to make sure

he didn't lose any votes because of foreign policy.

In 1992, one of the few times that Governor Clinton did take a strong

position in foreign policy was in Bosnia. He took a tougher position on Bosnia

than President Bush did.

Yes. Yugoslavia had broken up. There already was terrible turmoil and

bloodshed. The position of that preceding administration was, "We have no dog

in that fight," -- that we really had no national interest in what was

happening there. Governor Clinton and Senator Gore felt very differently.

They believed that we were seeing the worst atrocities in Europe since World

War II. They believed that if this was not stopped, it would embroil all of

Central Europe. And so we frequently spoke out on Bosnia during the

campaign.

Was that the first major foreign policy dilemma for the new administration-- squaring what Governor Clinton had said about Bosnia with reality on the

ground, once the new team took office?

We inherited three major crises when we came into office. . . . You always are

trying to launch your own initiatives in terms of things you want to see

achieved, but you're also inheriting the problems that are sitting there when

you come in. In our case it was Somalia, Haiti, and Bosnia. And we spent a

good part of the first two years trying to solve those three problems, as well

as dealing with the larger questions of enlarging and modernizing our alliances

and helping Russia and China make a transition. But those three problems

together were the big crises that we inherited.

. . . Bill Clinton spoke out so strongly about it during the campaign.

Then, when he first took office, he had to deal with it. Perhaps the world

wasn't ready to deal with it in as strong a way as Bill Clinton would have

liked. In fact, was he trapped a little bit?

![Over the eight years, that day, October 5th, 1993, [Somalia], certainly is

the low point.](../art/bergerpq2.gif) Things are often more complex when you're sitting in the White House than they

are on the campaign trail. As we took office, it became clear that the

Europeans had a different view of this problem than we did. We were prepared

much earlier than the Europeans to use NATO force against the Bosnian Serbs and

against the slaughter. And it took us really two years and a lot of horrible

incidents to really get the Europeans to understand that what they were doing,

which was admirable. They had forces on the ground in a UN force that were

essentially helping get food through to people so they wouldn't starve -- in a

sense, protecting the victims, but also shielding the victimizers. And it

really was with the massacres at Srebrenica two years later that Europe

galvanized, and saw that really this was not going to be solved unless Europe

used force to help resolve it.

Things are often more complex when you're sitting in the White House than they

are on the campaign trail. As we took office, it became clear that the

Europeans had a different view of this problem than we did. We were prepared

much earlier than the Europeans to use NATO force against the Bosnian Serbs and

against the slaughter. And it took us really two years and a lot of horrible

incidents to really get the Europeans to understand that what they were doing,

which was admirable. They had forces on the ground in a UN force that were

essentially helping get food through to people so they wouldn't starve -- in a

sense, protecting the victims, but also shielding the victimizers. And it

really was with the massacres at Srebrenica two years later that Europe

galvanized, and saw that really this was not going to be solved unless Europe

used force to help resolve it.

Did the president regret not committing American force earlier?

He was enormously frustrated during this period of 1993 and 1994. It was

fairly easy to build consensus with the United States government about what we

should do. It was much harder to get the Europeans to go along. And they were

on the ground. They had the equity, in a sense, of having soldiers on the

ground, of trying to alleviate the suffering. We did not. And as we tried to

convince them that that was not a long-term solution, they were pretty stubborn

about it. But as time went on, as the situation didn't get better, as the

slaughter continued, I think their attitude changed. I think they came

eventually to see things more as we did.

The summer of 1993, the first time President Clinton uses forces -- the

strike against Iraq. Do you remember anything about the president's decision

making at that point? When and how did he decide that it was right to go ahead

and strike against Iraq?

We had discovered that the Iraqis were responsible for a plot to assassinate

President Bush when he traveled to Kuwait. We operated a very small, highly

confidential group, until the evidence was unmistakable that this was an Iraqi

bomb that came from the government of Iraq. And we had the forensic evidence

to demonstrate that. I remember the night that we did this. Obviously, it's

always a sobering experience when you authorize the use of force. I think the

president felt that we had to do this to send a clear message that this kind of

official terrorism will not be tolerated, to establish a deterrent.

But then once we launched the strike, we were, of course, dark, so to speak, in

Baghdad. We actually were watching one of your competing networks, CNN, who

had cameras there. And the first indication that we had that targets had been

struck was actually from watching CNN. . . . This was something the president

we had to do, and I don't think that there was really much doubt in his mind

about it.

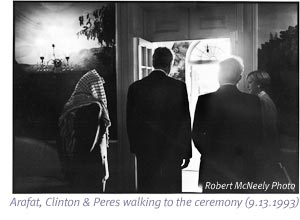

In September of that year, the culmination of the Oslo Accords is the

Arafat-Rabin handshake. What do you remember about that day?

It was obviously a very exciting and energizing day. I think there was

a sense that a new chapter had been opened. There was still deep distress

between Yitzhak Rabin and Arafat. We all remember the famous handshake, but

there was a conversation that took place before they went out, in which the

president said to Rabin, "You know, you'll have to shake his hand." He had not

done that before in all of the years and all of the negotiations that his

people had taken part in. And Rabin looked pained by this, because from

Rabin's point of view, Arafat would have been his enemy. And he said, in his

very taciturn way, "Okay, I guess." And then Rabin looked at the president and

he said, "But no kissing." And, of course, we then went out to the ceremony,

and we had that signing. The president brought the two together almost

physically to get them to shake hands, but the handshake was extremely

important symbolically.

It was obviously a very exciting and energizing day. I think there was

a sense that a new chapter had been opened. There was still deep distress

between Yitzhak Rabin and Arafat. We all remember the famous handshake, but

there was a conversation that took place before they went out, in which the

president said to Rabin, "You know, you'll have to shake his hand." He had not

done that before in all of the years and all of the negotiations that his

people had taken part in. And Rabin looked pained by this, because from

Rabin's point of view, Arafat would have been his enemy. And he said, in his

very taciturn way, "Okay, I guess." And then Rabin looked at the president and

he said, "But no kissing." And, of course, we then went out to the ceremony,

and we had that signing. The president brought the two together almost

physically to get them to shake hands, but the handshake was extremely

important symbolically.

Is that where Bill Clinton really got his inspiration about the Middle East?

He formed a bond with Rabin, particularly, at the time. He never campaigned on

making Middle East peace progress a cornerstone of his foreign policy. Is that

where the ideas would have began?

Every American president, really, going back to Richard Nixon, has

considered the Middle East to be one of the most difficult, dangerous and

important areas of US interest, and has been deeply involved in the process.

The president has actually had a longstanding personal interest in the Middle

East. I remember when he first met Rabin during the campaign, when Governor

Clinton met Rabin. . . . I think that Rabin saw this young fellow and didn't

quite know what to make of him. But a very close, fond and personal friendship

and partnership developed with Rabin over the years. That helped propel the

president forward, but I think just as importantly was his feeling that, in the

absence of a peace process in the Middle East, we will just see more turmoil.

So you describe a relationship with Rabin that began with Rabin not seeing

Clinton as his equal in any way, but which then developed?

Yes. I think it became a real partnership, a very close, personal friendship,

a true friendship, even though they were perhaps 20 years apart in age. I

would watch Rabin as he talked to the president. He had great respect for the

president, which developed over the years. And so, of course, his

assassination and the president's trip to the funeral were one of the sadder

moments of the last eight years.

I remember seeing a picture of the president at the funeral. He had

sunglasses on. You say he was personally quite moved by it.

. . . This was the death of a man that he admired greatly, who, in my judgment,

was one of the great men of our time. He also understood that it would have

consequences beyond the human and personal . . . for the peace process.

The US Rangers were ambushed in Mogadishu, also in 1993. How was Bill

Clinton told, and how did he react?

![Over the eight years, that day, October 5th, 1993, [Somalia], certainly is

the low point.](../art/bergerpq1.gif) It was certainly one of the darkest days of the last eight years. We

got called in the middle of the night. I think Tony Lake, who was the

national security advisor, called the president. It was a Sunday morning,

October 5, 1993. We came into the White House.

It was certainly one of the darkest days of the last eight years. We

got called in the middle of the night. I think Tony Lake, who was the

national security advisor, called the president. It was a Sunday morning,

October 5, 1993. We came into the White House.

The beginning of any of these episodes always has conflicting facts, and the

facts change -- how many people are killed, and is there still something going

on? Initial facts are always false -- that's the premise that I inculcate in

my staff -- don't jump to any conclusions based on the press wire story. But,

obviously, as we learned more about this, it was clear that we'd suffered a

terrible loss. It was a very, very difficult day.

Did Bill Clinton get personally angry about it? Could you tell that he was

quite upset?

He was certainly upset at a human level. He subsequently met with many

of the families of those 17 soldiers. Those were difficult meetings; poignant,

and in some cases, hard. We were not aware that this raid was going to take

place before it did, so I think he had a lot of questions about what had

happened.

Some people have described him as being visibly angered when he saw the

pictures of the American servicemen being dragged through the streets of

Mogadishu.

Absolutely, absolutely. Yes. He was revolted and furious, both at the

Aidid forces for having perpetrated this on the United States, and in trying to

determine how had this happened and what had gone wrong. In the following

days, there was quite a firestorm in Congress, with a very substantial number

of members saying that we need to pull out immediately. And even though we

were on the glad path to leave Somalia, I think the president felt that picking

up and running, even in the face of this kind of a horrible tragedy, would not

be good for the United States. He stood his ground with the Congress in a

very, very tense meeting with some of the members of the Senate and the House.

He said that the United States didn't turn tail and run even when terrible

things like this happened. He was able to succeed in convincing the Congress

that we should leave in a more orderly way, and turn this over to the United

Nations.

Absolutely, absolutely. Yes. He was revolted and furious, both at the

Aidid forces for having perpetrated this on the United States, and in trying to

determine how had this happened and what had gone wrong. In the following

days, there was quite a firestorm in Congress, with a very substantial number

of members saying that we need to pull out immediately. And even though we

were on the glad path to leave Somalia, I think the president felt that picking

up and running, even in the face of this kind of a horrible tragedy, would not

be good for the United States. He stood his ground with the Congress in a

very, very tense meeting with some of the members of the Senate and the House.

He said that the United States didn't turn tail and run even when terrible

things like this happened. He was able to succeed in convincing the Congress

that we should leave in a more orderly way, and turn this over to the United

Nations.

Tony Lake told us that he considered Somalia the low point of the American

foreign policy team during his tenure. Would you concur with that

assessment?

Yes. I would extend it to my tenure and this tenure. Over the last eight

years, that day, October 5, 1993, is certainly is the low point.

In addition to Somalia and Russia, in the fall of 1993, you have to deal

with the Haitian crisis. You've got refugees coming in, and the famous

incident where the Harlan County is off Port-au-Prince, and there's a

mob on the wharf there. And the picture that Americans see on their television

is the Harlan County retreating, turning tail. What was that like from

your vantage point?

I have to put this in context a bit. We had reached an agreement in 1993 with

the military leaders who had overthrown the Cedras-Francois regime to turn

power over, peacefully, to a new government over a period of time. As part of

that process, called the Governors Island process, we said that, at some point,

we'd send Seabees down to Haiti to help in civil projects, and to work with the

Haitian military in a cooperative way; and the government agreed to that. When

the Harlan County arrived, it was not there to invade Haiti -- it was

there to drop some Seabees off. That crowd at the dock was a statement by the

military leaders that they were abrogating their commitment to Governors

Island.

Looking back on it, I would have done it differently. Three days after we

pulled the Harlan County out, we took six warships and put out them

around Haiti, and said, "We're going to enforce this embargo 100 percent." And

I've often thought if we'd put the six warships around Haiti on day one, the

Harlan County could have left on day five, and no one would have paid

any attention. There's a good example; symbols do matter. I think the

way we handled it was a tactical mistake, but it was certainly not appropriate

for Harlan County, a bunch of guys who were basically engineers, to try

to fight their way into Haiti. That was not the purpose of it.

Symbols do matter, and these things are always viewed in a political

context as well. Given the problems that Bill Clinton had in foreign policy up

to this point, was seeing the public reaction to that symbol personally a

setback for him?

Yes. Certainly, the way that was handled was a mistake. He ultimately

bears responsibility for everything, but I'm not sure that he was the person

who decided to pull the Harlan County out that quickly. It would have

been far better had we made a statement of strength before we then got the

Seabees out of town. It was a failure to think this through carefully -- a

mistake that I hope we would not subsequently make.

. . . President Carter and Colin Powell and Sam Nunn are brokering an

agreement with the Cedras government to leave at the same time that the United

States is mounting a preparation to invade the island. What was the

president's decision-making process?

It was a very dramatic time. The president had decided when we imposed

strict sanctions to try to force Francois and Cedras out that he would have to

use military force if the sanctions did not work. So in a sense that decision

had been made earlier. We got the United Nations behind us. Actually, Carter,

Powell and Nunn went pretty much on their own, as we were on the verge of

sending this force in to try to negotiate an arrangement with Francois and

Cedras.

I remember standing in the Oval Office with the vice president, the secretary

of state, Tony Lake and others. We knew that, at four o'clock, our forces were

taking off, and the president had said to President Carter, "You go ahead and

do this. You try this, but you've got to be out of there at twelve o'clock."

And he said it a hundred times to President Carter.

Well, it got to be about 12 o'clock when President Carter called up the Oval

Office and said, "They've agreed to leave." And the president said, "When?"

And he said, "Well, they haven't said when. They just agreed to leave." Of

course, they'd agreed to leave four times previous. And the president said,

"That's not good enough. We need a date -- 30 days."

That was a critical decision for the president. It would have been a lot

easier at that point to simply say, "Okay. We'll accept some indefinite

promise." And I really I believe that the imminent departure of our

multinational force several hours later caused the Haitian military leaders to

decide that they'd better give us a date.

In April, 1995, there's Srebrenica. There were numerous press reports

early in the administration. There is a sense that foreign policy takes a back

burner in this administration. . . . What's your characterization of that

time? Was foreign policy relegated to the back seat?

No. I think that's just wrong. I've actually looked at how much time this

president has spent on foreign policy in the first term and the second term

compared with his predecessors, and he spent more time on it than his

predecessors, at least since the post-war period. Whether that's been

enlarging NATO, or peacemaking, or trying to deal with the international

economy, or fighting terrorism. He ran on a fundamentally domestic agenda, to

get the economy back on track. And the fact that he was able to do that has

been the greatest asset that the United States has had in the world that you

can imagine. The fact that we're the strongest economy in the world makes us

the strongest power in the world.

But I looked at the records for this president. For example, the president has

spoken to Prime Minister Barak 72 times between May, 1999, and

November-December of 2000. Seventy-two times. So it's not been neglected. .

. .

Well, did it change? Was foreign policy more on the back burner early in

the administration, compared to the second term?

I'm not sure that I would say that. I think what happened from the

first term to the second term is that we've been able to go from the inherited

agenda to our own agenda -- enlarging NATO and embracing new democracies, peace

in Northern Ireland, the peace process in the Middle East, trying to build up a

stronger relationship with China based on openness, and trying to work with

Russia. So in some ways, as time went on, the agenda shifted from what we

inherited in this post-Cold War period to what we were building.

In April, 1995, you had the terrible attack in Srebrenica. You had

respected people at the State Department resigning in protest. What kind of

pressure was Bill Clinton under at this point? You had Elie Wiesel at the

Holocaust Museum, pointing to the president in a very sort of poignant moment.

The president seemed to be under a lot of pressure.

He was both frustrated and angry - frustrated because, in fact we were

trying to move more forcefully, and angry that there was such resistance coming

from our allies. But when Srebrenica happened, I remember Jacques Chirac

called the president and said, "We must act," and it was a welcome statement.

That provided the catalyst for getting NATO engaged, and using air power. With

what was happening on the ground at that point, with the Croatians beginning to

win back some territory they lost, that led to Milosevic agreeing to go to

Dayton and negotiate a peace.

After Dayton, the president is also faced with the prospect of sending

troops, just as he's getting ready for an election year. Was that a difficult

thing to do for him?

. . . Whenever you deploy troops in any situation, there is risk. There

also was a mixed reaction on the Hill. It took a lot of persuasion by the

president to convince Congress, that having made the peace, having ended the

war, having created the peace, we now had an obligation to participate as the

leader of NATO in securing the peace.

I think, with the recent fall of Milosevic, you now have a democracy having

reclaimed all of the Balkans for the first time, and the opportunity to realize

a vision that the president first articulated in Brussels in 1994 -- which is a

Europe that is peaceful, democratic and undivided, for the first time in its

history. We're on the edge of that now, as a result of a number of things that

this president has done over the last eight years.

In the spring of 1996, China decided to test fire missiles over Taiwan, and

we responded by sending a carrier. How tense a time was this? Was this a more

precarious moment than many of us realized at the time?

It was a tense moment. The preceding several months had been a period

of great tension in US/China relations. President Lee of Taiwan had come to

the United States. We had granted him a visa to speak at Cornell. That was

very controversial. One can argue whether that was a good thing to do or the

wrong thing to do. But it certainly led to a serious deterioration in our

relationship with China, and I think was not unrelated to their provocation

against Taiwan.

I remember a breakfast meeting at the Pentagon with Secretary Perry, Secretary

Christopher, Tony Lake and myself. Secretary Perry proposed that we move two

carriers in closer to Taiwan as a strong signal to the Chinese that we believed

anything involving the future of Taiwan had to be resolved peacefully. It was

a move not without risk, but I think it turned out to be the right move.

Was the United States prepared at that time to use military force if China

had been aggressive toward Taiwan?

What we did turned out to be the appropriate act. We've always taken

the position that this needs to be resolved peacefully. We made that point

again to the Chinese after this recent election in Taiwan, in another period of

tension between Taiwan and China. And I think our posture was appropriate

there.

Did Bill Clinton think the Chinese were essentially bluffing on this?

He felt it was important that we make clear that we believe that

stability across the straits was important.

In January, 1998, the Lewinsky story breaks. Clinton has a cabinet meeting

on January 23. Were you at that meeting?

Yes.

After that meeting Secretaries Albright and Shalala, come out and say that

they believe the allegations are false. What was going through your mind at

that moment?

I think that all of us wanted to believe the president at that moment.

Later, when you found out the president wasn't telling the truth, what was

your reaction?

I was, obviously, disappointed in my president and my friend.

In 1998, while the scandal is going on, the president makes a number of

high-profile trips, including Africa and China. How did he deal with that at

the same time you had this raging scandal going on back in Washington?

We've always tried to keep foreign policy, national security policy,

separated from not only whatever domestic controversy might be going on, but

certainly also political cross-currents. And so it was a strange period. We

tried to conduct American foreign policy based on what was in the national

interest. That trip to Africa was an extraordinarily important trip. But I

often went home at night and called my daughter, who works for one of your

competing networks, to find out what had happened that day on the scandal

front. We really did try to keep a separation between that and foreign policy.

It was very important to the president, and it was very important to me to be

able to say to the Congress and the American people that any action we took, we

took on the basis of the national interest.

You're trying to conduct foreign policy in the interest of the country; at

the same time, you, like everyone else, is in a certain sense obsessed with

what's going on in terms of politics and the scandal in Washington. As a

practical matter, what's it like to operate in that kind of a condition?

I had a job, which was to take that Africa trip. It's the longest trip that

any president ever made to Africa. It was the first time an American president

had said to this continent of 700 million people, "We care about our future

with Africa. We believe there are important things happening here. We have a

stake in what goes on here." There was an enormous amount to do on that trip,

and my job was not to be the president's lawyer in that situation or his press

secretary. My job was to be his national security advisor, and to make sure

that our work in the world went on without interference. It's one of the

strengths of the United States that we have a tradition of keeping foreign

policy basically separate from other controversies or partisan politics.

Did you talk to the president about the scandal at that time? Or was it

understood that that wasn't something for you to talk to him about?

No, I did not talk to him frequently about it.

On August 17, the morning of the president's grand jury testimony, the White

House released a photo of you, Erskine Bowles and the president. We now know

that discussions were going on at that time about the Osama bin Laden attack

that was going to come a little bit later. The president is looking

particularly weary in this photograph. It's a difficult time for him. There

are these great big bags under his eyes. Do you remember that morning?

Yes. Again, to put this in a little context for your viewers, in

August, two of our embassies in Tanzania and Kenya had been bombed with over

200 killed, and 20 or more Americans. We had gone out to Andrews Air Force

base as those bodies came home. The president met with every one of their

families, as only he was able to do in situations like that, and to provide

some sense that their nation cared.

In the meantime, we were very intensely engaged in trying to determine who was

responsible. And we were able to do that relatively quickly. Sometimes these

things take a while, and sometimes the pieces of the puzzle come together quite

quickly. So within a month we knew, very clearly, without any doubt, that this

had been perpetrated by Osama bin Laden and his network. We proposed to the

president a retaliatory strike, both in Afghanistan, and in connection with a

chemical weapons-related facility in Sudan that was related to him.

Of course, secrecy was extremely important to this exercise, and the president

was going to Martha's Vineyard for a few days off. We were able to get him off

to Martha's Vineyard without any of your colleagues knowing what was about to

happen. And then once we launched the missiles, the president then came out to

speak to the American people.

Was it a concern at the moment that Bill Clinton's motives would be

questioned -- because he was launching this strike in the midst of a critical

moment in the scandal that was also going on?

Certainly I think we're aware that some people would raise this. But it's a

situation where you're damned if you do and you're damned if you don't, so you

might as well do what you think is the right thing to do. If we didn't act

because some people might think that it was to change the subject, that would

be indefensible, and we'd be roundly and properly criticized. If we did act,

some people would say it was to change the subject, and we'd be roundly and

sharply criticized. And I think in that situation I remember the president

saying, "Let's just do what we think is the right thing to do. We'll probably

get it either way." And I think the right thing to do was to respond, and we

did.

Going back to August 17, 1998, the president has his grand jury testimony.

Discussions are going on about Osama bin Laden. That night the president not

only had to address the nation about Monica Lewinsky, he was also having

national security briefings with you. What was that like?

The president is tough-minded. I don't know what was going on in his stomach.

I assume it was churning. But he dealt with the crisis that we were facing

with bin Laden calmly, clearly, and I think without, in my judgment, a sense of

being distracted by other matters. He's obviously a man of great intelligence,

and is able to focus and concentrate on what he has to do, and then clearly

there were other things that were going on that day.

Was he particularly anguished about this?

No. He was anguished by the loss of lives at that embassy and by our

vulnerability there, and what needed to be done to increase security at our

embassies in a new era in which terrorism is a bigger factor. Let me say

this: we spent a fair amount of time on what the targets were, about collateral

damage. Any time the president has used military force, he's been concerned

about minimizing damage to civilians, if that's possible, consistent with the

military mission. So we went over the targets carefully. But I don't think

there was any real hesitation in his mind about what the right thing to do

was.

In December, 1998, after Iraq fails to let the inspectors in, there's

another decision to use force. John Podesta told us that when he told senior

members on the Hill that the US was considering this response, he basically got

an earful. It was like, "Are you out of your minds to be doing this at a time

when the impeachment process is going on?" What was that like from your

perspective?

I have separated myself from those issues, and to the extent I can, from the

politics of the office. Not to say I'm not interested in it, but I'm trying to

remain separate from it, so I didn't get as much of that. As you recall, we

were ready to go. Once Saddam appeared to capitulate, we called off the

bombing. It was at a later time, when it was clear that he was not going to

capitulate, that we went forward with it. Again, during this period, you have

to decide what you thought the right thing to do for the country was, because

you're going to be criticized either way.

Did this make it much harder for you? There was a raging scandal going on,

the House is considering the impeachment of the United States president, and

you've got to make decisions about using military . . .

I've got to say that there is nothing that that we did that we would not

have done otherwise, or nothing we didn't do that we would have done otherwise.

It was most difficult as we traveled abroad during this period. The president

would stand up at a press conference in Moscow or in the Caribbean or in some

other country, and of course, the press wasn't terribly interested in what was

going on in his meeting with Yeltsin or his meeting with the CARACOM leaders.

So the questioning would be very much focused on the scandals here, on the

impeachment issue here. That was kind of puzzling to a lot of our foreign

friends, and somewhat disconcerting. But in terms of fundamental decisions, I

can honestly say that I don't believe anything was done differently.

About a month after the acquittal of the president in the Senate, the

president and your team decide to go ahead with the air strikes in Kosovo.

What was the breaking point there? How was that decision reached?

We have this history with Milosevic, and the legacy of it having taken

so long in Bosnia -- two years -- to actually act. Therefore, it's taken a

long time for Bosnia to come back, even after the peace. So I think we have an

acute sense that we needed to act at the outset of this crisis. We tried to

negotiate with Milosevic. He withdrew some of his forces. He went to

Rambouillet in a peace conference, or his people did, and said no. And at the

same time that he begins to amass 40,000 troops on the Kosovo border, the

killings in Kosovo increase. And the president was continually on the phone to

other NATO leaders, saying, "It's time for us to act. We must act together."

At this time, he convinced his NATO colleagues, many of whom were as committed

as he was that we had to go forward.

We sent Ambassador Holbrooke on one last mission for Milosevic to agree to

leave Serbia, and Milosevic said no. We went to NATO and got the order to

proceed with the air strikes, which then went on for what is probably 78 of the

most intense days of the president's period in office.

Intense in what way?

We're engaged in a war. Whatever you want to call it, it certainly felt like a

war. We had to simultaneously hold our domestic support, we had to hold the

alliance together, and we had to continue on this campaign. Don't forget --

this is the first time in NATO's 50 years, other than three or four days in

Bosnia, that it had ever been engaged in a sustained military action. And so

we also had to get NATO to work more effectively. Their ramp-up period in

terms of the air strikes were slower than we would have liked, simply because

this machine had never been taken out of the garage before

The really critical moment came in April, when it so happened that NATO was

meeting here in Washington for the fiftieth anniversary. This was a month into

the air campaign. And Milosevic's strategy was always, "Break the unity of

NATO." NATO operates by consensus. If the Italians or the Greeks or others

who are more sympathetic to the Serbs would split away, the NATO alliance would

fall apart.

We had a meeting with Prime Minister Blair and the president up in the

residence the night before this NATO meeting began. Secretary Albright was

there and myself. And the president said to Prime Minister Blair, "We cannot

lose." And Prime Minister Blair was of the same view. They went into that

NATO meeting the next day. The 19 leaders, now joined by the Czech Republic,

Hungary and Poland

-- three countries who had come in as new democracies -- the 19 leaders

essentially looked each other in the eye, and said, "We will not lose." It was

in that moment, in my judgment, that Milosevic lost the war. It took another

60 days of bombing, but he could not crack the unity of NATO.

As the bombing campaign goes on longer and longer, the criticism starts to

mount, in the United States and elsewhere, that you're relying too much on the

air war. The front page of the Washington Post suggests that

even some of the joint chiefs are second-guessing your strategy. Your own

senior military officials are questioning the soundness of your policy. How

did that add pressure to you and the president?

Certainly General Shelton and Secretary Cohen were strongly supportive

of the process, of the strategy, and in many ways, they were architects of it.

We believed the air campaign would win, and we had one fairly useful piece of

data to show that's correct: we did win. We lost no Americans.

There were times when I thought there were probably 15 people, not related to

me personally, who believed we could prevail: including the president,

secretary of state, and the secretary of defense. And there did come a point,

as we got into the summer, when we were beginning to face a crossroads. Had we

not begun to plan a land campaign at that point, we would have ultimately faced

a winter in which a lot of people would have frozen.

I always believed that a debate early on about a land war would have so split

the alliance, and split this country, that we would not have been able to go

forward. But as we got into June, it became clear that we were facing that

moment of truth. I remember staying up most of the night in my office in the

White House. I was one of the few people there, writing a memo to the

president. I said that within the next week we would have to decide between a

lot of very unpalatable options, including a land ground invasion involving

maybe 100,000 to 200,000 Americans, but that we had very little choice.

Simultaneously, we have an initiative to try to get Milosevic to capitulate,

between the president of Finland, Mr. Ahtisaari, and Victor Chernomyrdin, the

prime minister of Russia in a meeting with Milosevic. Actually, before my

memo was typed and sent to the president saying, "We now really have to

seriously be ready to go in a ground campaign," Milosevic capitulated.

When the president addressed the American people early on in the air war, he

ruled out ground forces. Was that a mistake, in retrospect?

No, I don't think it was a mistake. He said something like, "I have no

intention," or "do not intend to." So it was not "I never will." It was a

sentence inserted deliberately, and I guess I take a responsibility for it.

Had we had a great debate back then about whether we should have a ground

invasion of Kosovo, even though that was not our intention, we never would have

got off the ground. We would have had a huge debate here. We would have had a

huge debate in NATO, and we never would have acted.

As we got deeper into this and it became clear that you might have to have that

option, the president said, "Nothing is off the table. Put it back on the

table." But I believe had we provoked that debate in the beginning, when that

was not our strategy and that was not our intention, that we never would have

acted.

Was it difficult when you were getting criticism even from people like

General Clark, who felt that you had to ramp up earlier for a ground war?

At that same meeting that I discussed earlier with Gore and Clinton in

April during the NATO meeting, they agreed that we should quietly encourage

planning within NATO for a possible ground campaign if that became necessary.

And so General Clark had developed a plan. He knew what needed to be done.

The issue really came to the forefront as we got deep into May, early into

June, given the lead times. You had 200,000 people in Kosovo who, if had you

gone into a winter, might have died if you couldn't either end the war or

somehow get in there. I think we were moving towards a decision concerning

ground forces while we were simultaneously increasing the pressure on Milosevic

to the point where he put up the white flag.

When you look at the president's decision making in foreign affairs, how do

you compare the president, let's say, back in Haiti, with his decision making

in Kosovo? What change did you see over that period of time?

Nothing prepares someone to make a decision to send American men and

women into combat or into harm's way. And so I would say that in the early

days -- and Haiti is a good example -- that we deliberated, and deliberated and

deliberated. We turned the issue upside down and left to right. . . .

You were not as decisive as you might have been?

We left no stone unturned. Obviously, we were very concerned about making sure

that every, every element of this had been considered. I think when you get to

Kosovo, you fast forward. The president made a fundamental decision that the

United States and NATO could not stand in the last year of the twentieth

century -- the bloodiest century in history -- and see that century end with

the vindication of ethnic cleansing and with a wider war in Europe. And so he

made a decision that we had to act.

And from that point on, he was actually unshakable, and didn't second guess.

He, obviously, was concerned every day with what was happening. There were

decisions that had to be made along the way. But he was an absolute rock

during all of that period, both with respect to the alliance, and with respect

to his administration. As you indicated before, people were saying is that

this the right strategy. And he inevitably became a stronger and more

confident leader as time went on.

So if you were going to characterize that change in the president, he became

more decisive and more comfortable with his own instincts?

I would say more that he sized his engagement more carefully to the

magnitude of the problem. In other words, he was not the vice chief of staff

of the army, he was the commander in chief. It was not his job to look at the

details. His job was to make the fundamental decision to rally the world and

his country behind it, to keep his administration on course; to make sure that

his team had the right direction, but to let his team then run the operation.

When Milosevic falls a couple of weeks ago, what do you remember about that

day and your conversations with the president? Demonstrations were scheduled

that morning, and they start spiraling throughout the day. Did you talk to the

president?

Oh, yes. And it was an extraordinary day. Think about this. Milosevic

started his rampage in 1991, before we arrived, and had preoccupied us in many

ways for most of our administration. We supported the opposition very strongly

in ways that were appropriate during that election to oust Milosevic. And so

when you saw Milosevic toppled and fall like a ship that sinks, it was a great

sense of power of the people, the power of democracy, and vindication for

having stuck with it for as long as we did.

But there's one thing about leading and being engaged in these kinds of things

-- you don't get to enjoy your victories very long. The next day, things began

to unravel in the Middle East. And so, notwithstanding the fact that in a

single week we had signed a bill to let China into the WTO, Milosevic had

fallen, and a number of other positive things that happened, we got to savor

that for maybe 24 hours, and then we turn and throw ourselves into a crisis in

the Middle East.

In July, at Camp David, the president is trying to broker some kind of

understanding on the Middle East, and it falls apart. He's shuttling between

the delegations late at night. Ultimately, it fails. Why did the president

think he could accomplish something of that magnitude?

The parties themselves, Barak and Arafat, had set September 13 as the deadline

for completing the final status negotiations. It was quite clear that had

nothing happened by then, we were headed for a terrible confrontation. And in

fact things were deteriorating. There were demonstrations and riots in May,

which I think began to foreshadow the frustration and anger there. The

situation was deteriorating on the ground. But having spent a fair amount of

time talking to both parties, some sensed that they were not as completely

apart as they might appear, and they were totally unable to deal with it

themselves. They were totally unable to make any more progress themselves.

Prime Minister Barak felt very, very strongly that the only way in which this

could be potentially resolved would be to bring the leaders together in an

isolated environment, where compromises could be made without every single

position being scrutinized by the public and the press, and you can come

together with a package. And I think we made quite extraordinary progress. I

don't know anybody who could have done what the president did in those

negotiations or what he did in the Wye negotiations or many other

circumstances. He is able to help bridge differences, and help to close gaps

through a combination of intellectual power, a sympathetic ear, listening to

others, with respect from and for both sides. And we got actually far closer

at Camp David than ever before, but not, unfortunately, to total closure. . .

.

There was a news blackout there. During this period, all the public saw

were these still pictures of the president late at night shuttling back and

forth through the different sides. Was the president relying too much on his

own political skill, his own charm? Was there some hubris in suggesting that

he might be able to make an agreement here, given how far apart Barak and

Arafat . . .

No, I don't think so at all. First of all, this was something that Prime

Minister Barak had been insisting upon for over a month. Chairman Arafat also

wanted a summit. He wanted to put it closer to the September 13 deadline,

which he thought would give him more leverage. We thought a little bit of

distance from that deadline would create a little more space.

But I don't think that the president felt that, through some magical power, you

can breach differences that have existed for, in some cases, centuries; in same

cases, 50 years; and in some cases, since the Oslo process. These are very

hard issues of how you make peace in the Middle East, and they have not been

solved up until now, and I hope they will be solved. Some progress was made at

Camp David. I think both parties felt there was.

But sometimes you have to try in a situation where you know that the

consequences of not trying are certain. The consequences of our not having

gone to Camp David would have been turmoil breaking out. Now, as it turned

out, we made progress, but by virtue of subsequent events, we've had a very,

very difficult patch.

At the end of that process, the president came out, and he praised Barak,

and specifically left Arafat out of that compliment. Was the president miffed?

Was he upset with Arafat at Camp David?

He was trying to describe the situation in a fairly factual way; that

Prime Minister Barak did show more flexibility on more of the hard issues than

Chairman Arafat did. . . .

Did the president feel personally let down by that?

I don't think anybody went into Camp David with an unrealistic

expectation that this was easy. Everybody believed it was very difficult, but

I think they believed also that the parties wanted this to happen, that they

wanted to try to do this, and that the consequences of not trying were quite

clear.

Now that the process is in deep trouble, does the president believe that

something he had hoped to leave as part of his legacy -- the peace process --

has failed?

It's the parties that determine the future of the Middle East, not the

United States. Some things are better. We have peace between Jordan and

Israel as a result of the efforts of this administration. Obviously, it would

be far better if there were some kind of a negotiated resolution of the

situation between Israelis and Palestinians, but that's not been possible for

the last 52 years. I hope it will not take 52 years to be able to make it

happen.

Clinton had invested so much in the Middle East through the various Camp

David agreements. He met with Arafat more than any other foreign leader, and

there was an enormous personal contribution here. What was the president's

personal reaction when it fell apart in the fall of 2000?

He thinks this is a tragedy. This is two peoples who are side by side.

That fact is not going to change. And either they will descend into conflict,

which has the potential for engaging the broader region, or they will find a

way back into some kind of negotiating process. But as we sit here now, the

most important objective is to try to break this cycle of violence. It's in

everyone's interest to try to do that.

You had to make the phone call to the president the morning that USS

Cole had been bombed in Yemen and also the same day that the Israeli

soldiers were murdered. What was that phone call like?

We've gotten used to these calls. He's probably more civil on the phone

at three o'clock in the morning than I am when I get the phone calls from the

Situation Room. In most of these cases, the president has just wanted facts.

He's wanted to know what do we know, what's happened, what do you recommend

that we do next with what is going on, what's in process? At three o'clock in

the morning, you're perhaps more professional than you are reflective.

Here you had two incredible bits of news. Can you tell us more about that

particular call?

The first information is usually wrong and often quite fragmentary. So

all that we knew when I called the president was that there had been some kind

of attack on the Cole. The casualty number that I had was initially

much different -- it was much smaller, one or two Americans killed. Not that

that's not important, but it's obviously a different order of magnitude than 17

killed. He asked me a lot of factual questions. . . .

After the Cole was attacked, did the president make it clear that the

United States would respond once it found out who was responsible?

Yes, absolutely. We have intensified our efforts and posture very

substantially, and tripled the amount of money we're spending for it during

this administration. We finally found the perpetrators of the World Trade

Center bombing. We've brought Mr. Kasi back from the Philippines, who had done

that terrible shooting at the CIA. We have suspects in Khobar [Towers bombing

in Saudi Arabia] that are in prison in Saudi Arabia. We reacted against the

Iraqis, we reacted against Osama bin Laden. The United States has to

understand that there is a new war going on here. We have to be equally

aggressive and strong, both in trying to prevent, and trying to protect, and

trying to increase deterrence by making sure that we respond when we have

certain information about who's responsible.

One of the president's last trips in office will be to Vietnam. Why did the

president decide that that was important, and why did he wait so long in his

administration to do that?

We've spent eight years very carefully moving towards normalization with

Vietnam. And we've kept one issue at the forefront of that process, and that

has been accountability for POWs and MIAs. When we started this process back

in 1993 and 1994, the Vietnamese were not cooperating with us very much at all.

And over the years, each step that we've taken along the process of

normalization has been as a result of their opening up their files, of their

agreeing to joint excavation, of their agreeing essentially to be partners with

us in trying to account for our missing.

And so only when we were satisfied that we really were getting cooperation did

we move to normalization. The next step was to enter into an economic

agreement with Vietnam. And so it's now really right for the president to go.

This will be an important trip, both in the sense that it will end a chapter of

American history -- or at least, if not end it, write another closing chapter,

as well as turning towards the future of our relations in Southeast Asia and

our relations with Vietnam.

Relations in Asia also appear to be warming with North Korea, where

Secretary Albright . . . Has the president talked about going to North Korea

himself?

We have discussed the possibility when Secretary Albright returned, but

we have not made any decisions. Something significant is happening in North

Korea. The secretary had a good visit there. We have an interest in

encouraging the process of reconciliation between North and South, which so

boldly has been pursued by the South Korean president, Kim Dae-jung. And I

understand America's interest to foster that process if we can do so in a way

that is careful, and cautious, serves our national interests, and has no

illusions about the nature of the regime in North Korea or the capability they

still have to cause trouble. We'll make a decision about that over the next

several weeks, depending on where we are in answering those questions.

It's too early for history to have been written. But how do you see the

Clinton legacy in foreign policy, both for good and bad?

This president will be seen as a president who began to define America's

role in a new global age. We spent 50 years defining America during the period

of the Cold War in terms of what we were against, and then maybe a decade in

terms of what collapsed post-Cold War. We came into office at a time when we

really needed to build America's role, a time of great strength in terms of

what our interests were. We tried to do that by expanding and modernizing our

alliances, trying to make peace around the world, by being a peacemaker, by

trying to deal with the new threats like the terrorism that I spoke of, by

trying to bring old adversaries like Russia and China into the global system,

and by recognizing that an open global economy is one that is in America's

interests.

So I think that the president will get high grades. The accomplishments of

this president in foreign policy range from peace in Northern Ireland, to

expanding NATO, from bringing China into the global system, to opening to

Africa, to putting AIDS on the international agenda, and other issues like

climate change. I think that, across a wide range of issues, he'll be seen as

the beginning of defining America's role in the global age.

If you could list one regret that Bill Clinton has about the way he

conducted foreign policy, what would that be?

There have certainly been terrible setbacks along the way. We've talked

about Somalia, and other events that did not go as we would liked. I suspect

that he would say that he had hoped that we would have ended this

administration with a more secure peace in the Middle East than appears will be

the case.

You talked about the president changing in a couple of ways in foreign

policy. You suggested he became more decisive, and that he began to focus on

the bigger picture instead of the details. Is there one particular moment that

stands out, where you noticed that the president had made kind of a fundamental

shift in the way that he handled these crises? Was there one particular moment

in terms of how the president handled foreign policy where you looked at him

and thought, "This man has really grown?"

It's an evolutionary process for any president, but I'll give you an example in

1996. Mexico faced a terrible financial crisis. The president had called the

congressional leaders down to the White House. He said, "We've got to deal

with this. If Mexico collapses next door, the consequences for Latin America

and for the United States will be really severe." After several weeks of

trying to get congressional support for us to legislatively act together, it

was clear that there was no congressional support. Eighty percent of the

American people were against this.

I remember the night that Bob Rubin and Larry Sommers came into the White

House, and they had concluded that we had about 48 hours, and Mexico was really

going to go collapse. We went into the Oval Office. Secretary Rubin laid out

this problem. The president hesitated for half a second, and he said, "We

have to do it. It's the right thing for us, and it's the right thing for

Mexico." I felt compelled to tell him all the downsides, to make sure he was

aware of the risks. So I said, "This could happen: Congress could take away

our authority to act here. Eighty percent of the American people . . ."

. . . are against it."

And he had already processed all that. He clearly didn't need my recitation,

although I thought I had an obligation to do so. He just did what he thought

was right. And I saw that increasingly, as time went on. His leadership in

Kosovo, in the world, the alliance, his own country and his own government, was

really quite superb.

|  |