In this New York Times article (March 2006), Paul J. Lim outlines young workers' mistakes in managing their 401(k)s and what experts' recommend they should do, so that 40 years from now, they have accumulated enough for a comfortable retirement.

From The New York Times on the Web © The New York Times Company. Reprinted with permission.

- Related Features

- Poll: How Are You Doing?

Take FRONTLINE'S Poll on how you're doing - Financial Caculators

Figure out where you stand in saving for retirement - and how long your money will last. - Generation Y -- A Short Survey

FRONTLINE asked several young adults how they think about retirement and saving, and what they're doing about it. - Web Links for Young Investors

In today's ''do-it-yourself'' but ''don't know if my pension will be around tomorrow'' world of retirement, it's only natural for baby boomers to seek financial advice.

What's surprising, though, is the advice they want most. ''Our expectation was that it would have to do with Social Security, pensions, or health care,'' said Craig Brimhall, vice president for retirement wealth strategies at Ameriprise Financial, which recently studied attitudes on retirement.

But those topics tied for second and third place in the Ameriprise survey. Instead, a majority of older workers said what they most needed was advice on how to teach their own children about money and finances.

These parents may be on to something.

For all the mistakes older workers make saving and investing for their own retirement, their kids are doing an even worse job managing their 401(k)'s.

Hewitt Associates, an employee benefits consulting firm based in Lincolnshire, Ill., recently studied how the different generations are handling their employer-sponsored retirement assets.

Among its findings are these: Only 31 percent of Generation Y workers (those age 18 to 25) eligible to participate in a tax-deferred 401(k) retirement plan are doing so. By comparison, 63 percent of eligible Generation X workers (those age 26 to 41) are using these plans, while 72 percent of baby boomers (age 42 to 59) are doing so.

Hewitt forecasts that the average Gen Y worker at a large corporation who doesn't contribute can expect to replace just 43 percent of preretirement income upon retirement, based on current Social Security assumptions. Young workers who do take advantage of 401(k)'s stand a good chance of replacing all of their preretirement income, thanks in large part to the power of compound returns over several decades.

Retirement is probably the last thing on the minds of people in their 20's, who are entering the work force with college loans and credit card debt in tow.

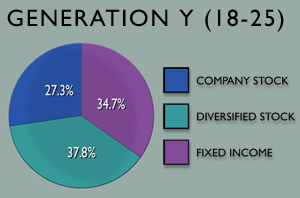

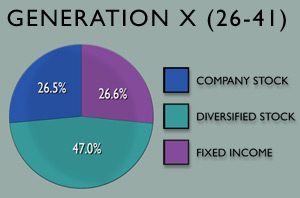

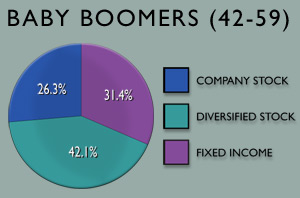

But what's unsettling is that even though most young workers realize that they're on their own when it comes to saving for retirement, many of those investing in 401(k)'s haven't a clue how to allocate their funds. The average Gen Y worker puts about 35 cents of every investment dollar into fixed-income options like bond funds and so-called stable-value funds, which are bond-like vehicles. This means the youngest workers are investing even more conservatively than their parents, who on average keep only 31.4 percent of their 401(k) money in bonds, according to Hewitt.

"Conservative Before Their Time"

Though they have more time to invest, young workers are keeping more of their 401(k) money in bonds than older investors are. Figures (below) are based on a 2005 study by Hewitt Associates of how 2.5 million eligible employees and 1.6 million participants in 107 large corporate 401(k) plans managed their money.

Figures do not add to 100 because of rounding.

Richard A. Davies, executive vice president for retirement and college savings at AllianceBernstein Investments, said Gen Y workers were fairly close to having a 60/40 allocation between stocks and bonds. But ''a 60/40 balance is about the right asset allocation for a 65-year-old, not a 25-year-old,'' he said.

Why are young workers so conservative?

Part of it may have to do with timing, said Ivory Johnson, director of financial planning at the Scarborough Group, an investment advisory firm based in Annapolis, Md. ''When the markets went down in 2000 and 2001, that's when these kids were in college,'' Mr. Johnson said. ''So their first impression of the stock market was that it could lose lots of money.''

Lori Lucas, Hewitt's director of retirement research, said other factors were also at work. Some young workers who sign up for 401(k)'s but fail to select investment options may be placed by their plans into the safest choices, like a money market fund. Many of these workers simply haven't gotten around to shifting money out of the default options.

Young investors in their 20's should probably keep 90 percent if not all of 401(k) assets in a diversified mix of equities, said Mr. Davies of AllianceBernstein.

Why? There are two basic sets of risks when it comes to investing. The first involves potential short-term losses you can suffer by exposing money to equities. But the second -- and equally important risk -- is that over long periods, the purchasing power of your money will be eaten up by inflation.

The younger you are -- and the more time you have to invest -- the more important it is to focus on the latter risk, said Stuart L. Ritter, a financial planner with T. Rowe Price in Baltimore. And since stocks are more effective in outrunning inflation than bonds, you should invest most of your 401(k) money in equities.

The fact is, your 20's are an ideal time to be betting on stocks. For starters, when you're young, you have little to lose. The average Generation Y 401(k) investor has only saved $3,200, according to Hewitt.

That means if you invested 100 percent of that money in stocks and saw your investments fall by 50 percent -- which is nearly how much the Standard & Poor's 500 index fell from its peak on March 24, 2000, to its trough on Oct. 9, 2002 -- you'd be out $1,600.

On the other hand, the typical boomer has nearly $93,200 saved up in their 401(k), according to Hewitt. A similar all-equity position that loses 50 percent would erase $46,600. That's real money.

But it's not just about potential losses. Between 1956 and 2005, a 100 percent stock allocation has generated average annual returns of 10.44 percent, according to T. Rowe Price. By contrast, a 60 percent stock, 40 percent bond and cash strategy has resulted in average annual gains of 9.09 percent -- or 1.35 percentage points less.

While this doesn't sound like a lot, it can make a huge difference over time. AllianceBernstein found that an investor who starts contributing to a 401(k) at 25 and continues saving until 65 could end up with 10 additional years of retirement spending by adding just 1 percentage point to annual returns.

A simple choice for younger workers who are unsure how to invest is to put all or most of a 401(k) into a so-called target-date retirement fund. These increasingly popular options, which are also called life-cycle funds, are all-in-one portfolios that invest in a mix of stocks and bonds that are appropriate for an investor's age -- and they automatically adjust that mix over time. Most life-cycle funds suitable for people in their 20's will start off with 80 percent to 100 percent in equities.

It is even more important to encourage young workers who aren't currently saving to contribute to their 401(k)'s. Mr. Ritter thinks one reason why people in their 20's aren't participating is because they aren't confident they know enough to invest. ''People get concerned about making the wrong decisions,'' he said. ''So they end up making no decisions.''

But for young workers, the wrong decision is to let your fear of investing -- and your fear of investing aggressively -- dictate your moves.