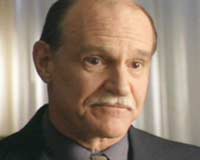

David L. Wray is President of the Profit Sharing/401k Council of America (PSCA), a nonprofit advocacy group representing 1,200 companies with profit-sharing plans, including the 401(k) plan. In this interview, Wray discusses the birth of the 401(k) plan, why companies today are choosing 401(k) plans over traditional lifetime pension plans, what employees need to save for retirement, the problems with 401(k) plans and how to fix them. This is an edited transcript of an interview conducted on Feb. 17, 2006.

- Some Highlights from this Interview

- 401(k) participation today, and the savings rate

- How much to save

- Problems with 401(k) plans, and how to fix them

Editor's Note: Wray has written a response to the FRONTLINE program. Read it, and FRONTLINE's reply, here.

How did the 401(k) provision get written into law, and why?

The 401(k) provision was written into law to do something entirely different than what it ended up doing. What we had back in the 1970s, and actually for decades before, was something called cash and deferred profit-sharing plans. In these programs, profit-sharing bonuses were available to employees, and they could choose to take the money in cash or defer the money into a profit-sharing trust. When ERISA [Employee Retirement Income Security Act], which was a significant pension bill passed in 1974, was adopted, it inadvertently left out authorization to continue this practice, so the supporters of ... this program ... went to Washington and said, "We need a technical fix."

So in the Technical Corrections Act of 197[9], a one-line new provision was added, 401(k), and it said employee contributions could be tax-deferred. It ... was meant to address these cash and deferred plans. But in 1981, the Internal Revenue Service interpreted that to mean any kind of employee contribution, so any kind of W-2 earnings that were deferred into a profit-sharing trust would receive special tax treatment. And boom -- the race was on.

So this is a technical fix with fairly narrow intent, and you get this explosion. How did that happen? ... By say, 1984, how many people were in these 401(k) plans?

By 1984, there were about 9 million people in these programs, and the reason for that was there was already an infrastructure in place, so that these weren't brand-new programs. ... A whole lot of companies already ... had what were called thrift savings profit-sharing plans, and they immediately converted their plans over to [401(k)s]. ... All you had to do was make relatively minor changes to an already-existing structure, and people who before hadn't been able to save on a tax-deferred basis could do so almost immediately. ...

So there's ... the old-line financial institutions who were deeply involved in [the] defined benefit system, investing millions of dollars, maybe hundreds of millions of dollars, for large corporations, and the mutual funds, who suddenly see a great new market. What did you see going on at that time?

The way that the money in the retirement system was managed generally was through, as you say, traditional financial institutions. ... The banks basically managed the money. .... But when you had a new idea ... that you're going to have people voluntarily saving their own money in individual accounts, the mutual funds said: "That's what we do. We help individuals save money in individual accounts." They had very sophisticated record-keeping systems; they had sophisticated communication programs. It was a clear fit between their kind of service ... and the new 401(k) idea.

... The mutual funds ... engaged in a very significant marketing campaign, and one of those companies especially was successful. At this time, Fidelity Magellan, managed by Peter Lynch, was [on] the front pages of the financial sections of the newspapers of America. Fidelity was very successful in going to companies and saying: "We have this new program. You want people to voluntarily invest in your program; you want them to feel good about what you're investing in and have confidence that it's well managed. Put your money into the Magellan Fund, because it's managed by Peter Lynch, and show your employees those newspaper articles. This will help jump-start your program." They were very successful in convincing people of that, and that's one of the reasons why Fidelity got off to a faster start than anyone, and they have, of course, preserved their lead to this day.

Do you find, looking back, that it is the large, blue-plate companies of America -- the General Motors, General Electric, IBM, Exxon -- who are leading the way, or do you find that it's medium and smaller companies that are really the fastest to grab this new vehicle?

The fastest to grab the new vehicle were the larger companies. Larger companies have always recruited top talent, using what I would [call] the premium benefit approaches. ... So the large companies led the way, ... and to this day, traditionally the large companies lead the way with new innovations. The small companies watch, and they imitate and follow. ... The small- or medium-sized companies always have preferred a defined contribution solution. They don't have the profitability, security and predictability to make the long-term commitment that a defined benefit plan requires.

So what you see is the 401(k) plan in the big Fortune 500 companies [is] the supplemental plan initially, and in the medium and smaller companies, it's the plan. ... Participation in 401(k)s, as a percentage of the workforce, is what? And compared to defined benefit plans?

In 1980 there were twice as many people in defined benefit plans, the traditional [pensions], [as] in defined contribution plans. That has flipped. There are now twice as many people in defined contribution plans as in defined benefit plans. There's been a complete reversal of what was true 25 years ago. ...

There are a number of companies now -- blue-chip companies like IBM, like Motorola, like Hewlett-Packard, Verizon -- who are freezing their old, traditional plans. Whoever has got the benefits, they get them when they retire, but nobody new gets them. And then you find another bunch of companies that are going into bankruptcy and defaulting on their plans, turning it over to the government. ... So you're seeing large companies really replacing their old lifetime defined benefit plan with the 401(k).

The traditional defined benefit system grew up in a different economic environment. It grew up in a time when American business dominated the world economy. Very large companies especially owned whole segments of the world economy. The American automobile manufacturers were giants compared to anyone else, and they were able at that time to comfortably make very long-term commitments, because they were playing in a United States-only field, and ... you could make these long promises because everybody else was, too.

In the 1980s, that began to change. In the 1970s and 1980s, we talked about how Japan was going to take over. We had tremendous inroads made against American manufacturing worldwide. Competition got very intense. Other countries didn't have the same ... approaches to the labor force, so companies were pushed into a situation where they needed a lot more financial flexibility if they were going succeed long term. More and more companies found that it was difficult to maintain the long-term promise that they'd made.

Along with that was the fact that Congress changed the rules almost on an annual basis for these traditional defined benefit plans. Not only was it harder to look way out and know that you could make your funding promise, but you didn't even know what your funding promise was, because the rules were constantly being tweaked. ... The combination of this global economic competition and the constant changes in the rules made it tougher and tougher for companies to have defined benefit plans.

When we leap forward to today, the global competition is even fiercer. In a global competitive environment, you can't do that. You have to have the financial flexibility to spend that money on new redesign of some product -- not putting money into a benefit plan. ...

Plus, there was a change in the dynamics in the workforce. The anticipation when these programs were put in place is that people would work in a single company. They would work there for 35 years; they would get a pension and a gold watch. We know today the typical employee works six, seven, eight years at each company. There's a lot of turnover. ... [A] defined contribution plan like a 401(k) is a much better retirement program for somebody who changes jobs several times during their lifetime.

What does it mean when an IBM decides, "We're going to 401(k); we're ending our commitment in the future to lifetime pensions"? Is IBM a bellwether, so that ... companies that have been sitting on the edge, trying to figure out what to do, are going to be swung by IBM?

I think that what IBM does will have an impact, but more importantly, what happens in Congress probably has an impact. There is pension legislation in Congress right now that deals with the funding of defined benefit pension plans. It's uncertain how those issues will be resolved. A lot of companies are watching that carefully, and so if you put the two together, you might have action. ...

Are you saying that if Congress significantly tightens the rules to really push companies to fund their defined benefit plans, companies are going to bail out of those plans?

Companies are in a particular position because of past laws, and if Congress changes the law and does not give companies a sufficient transition period to deal with those changes, the companies will have no choice.

I've seen some studies by the Congressional Research Service and by the General Accounting Office. While not universal, they're reasonable-sized samples of hundreds of companies, and the majority of them were putting less money into the defined contribution plan than they were into the defined benefit plan. And there certainly are a fair number of newspaper stories out dealing with companies, including IBM, in which the companies state quite clearly and openly when they make the conversion that they fully expect to save billions of dollars over the next several years. Aren't corporations being driven to move away from the old plan, the traditional lifetime pension, to the 401(k) in good measure because they're going to save a lot of money?

Some companies are moving from a defined benefit plan to a defined contribution model to save money, because the demographics have caught up with them. In the 1950s, when a lot of young people were hired after World War II, ... a defined benefit plan was very inexpensive, because you had a very long funding curve. You could make very small contributions to the program.

It took a long time for people to work to retirement.

Right, and you had a long time to accumulate money. ... When your average workforce as a whole ages, the cost of the defined benefit plan goes up drastically. ... So yes, they're going to save money, but the reason they're saving money is because there wasn't enough money set aside to take care of this demographic aging of the workforce. ... In the 1990s, many companies with defined benefit plans made no company contributions to the plan whatsoever, so those plans were not costing anything, because the marketplace, the growth in equities was going up. ... Now they're faced with these enormous amounts, and they're looking for alternatives.

Talk about the 401(k) plan in the 1990s stock market. We had this phenomenon; ... you just had a honeymoon period for 401(k)s in the 1990s stock market, didn't you?

If you look at traditional investment in defined contribution plans, it was relatively conservative. The mutual funds entered the program with their equity funds, and ... the asset allocation in the defined contribution plans shifted. It was about 50 percent in equities, 50 percent in fixed investments in 1990. The stock market started going up. All of us in America looked at that booming stock market. We wanted to be part of that. The 401(k) participants were exactly the same way. They looked to their employers to give them a way to invest in the market. There was just a true boom in interest in 401(k)s as a way to invest in equities, ... and for 10 years, we had this great ride. People were excited about this. They watched television and got their investment tips on TV. Of course, reality came around in 2000, and I think we're in a different place today than we were then.

With the rise of the 401(k), the enormous popularity -- give us the numbers now. How many people are involved? What are the assets?

The growth in the assets has been unbelievable. If you look at all of the different kinds of programs, what you see is in the private 401(k) marketplace, it's about $2 trillion, and it's another half trillion dollars from all the other sources. So it's probably $2.5 trillion at least, and that's up from virtually nothing 25 years ago.

Listening to that, I would have thought that the savings rate in America was going through the roof. I would have thought the success of the 401(k)s meant that, as a nation, we were saving like crazy. But you talk to people, and the savings rate is negative. We're not saving. How do you explain that?

The definition of "savings rate" is based on what I believe are antiquated calculations. We do not count capital gains in the savings rate, and a substantial portion of the ... money that's in 401(k) plans is capital gains growth. That is not counted as savings. ... We've really moved to a different kind of savings, where people are building wealth instead of savings accounts.

The other thing is that the savings rates are distorted by the demographics. We are moving to more and more people over the age of 65; those people are net spenders, so we have more and more people who are drawing down their assets. When you look at the savings rate as a whole, what you see is a big savings drain by people over the age of 65.

But you also have record levels of personal bankruptcies; you also have record levels of consumer debt. So the very people who are accumulating money in 401(k)s are also accumulating consumer debt. ... So these numbers have got to be put together. That's why we come up with something called the national savings rate. ... It seems as though the enormous figures in the 401(k) plans would point to a sensational success of savings in America, but the numbers don't confirm that.

... There's a tremendous amount of debt, but if you look at the balance sheet that currently exists in this country, I think the balance sheet is $50 trillion, and I believe that it's up 10 percent in the last year. This is ... using Federal Reserve numbers. So the growth in net wealth -- is substantial, but the savings rate, because it doesn't count wealth in the same way, ... that's going to get worse. ... If you look at all the retirement assets in the United States, it's $13.36 trillion. That's a lot of money. It's a lot of money. ...

I [have to] say, when I listen to you telling me that I shouldn't pay attention to people like Alan Greenspan, the former Federal Reserve chairman, and David Walker, the comptroller general of the United States, both of whom express dismay at the low savings rate in America, are you telling me they're crazy?

I actually agree that the savings rate is inadequate. ... The fact that the savings rate is inadequate, I think, is beyond dispute. ... People who talk about the savings rate, I think that they need to put it in the right perspective. [It's] not that Americans are behaving in ways that are much worse than they ever did, because I don't believe that that's true. I think that working Americans continue to save and consume. They buy houses; they [buy] cars; they do all those things. What we have to do is convince them that they need to save more than they have in the past, that they need to step up and realize that the way that they managed their lives before -- or that their parents managed their lives -- [is] not the same as the way they have to do it. ... But I don't think it's fair to say that something about American workers is different today than it was in the past.

No, I wasn't suggesting it was different. I just expected that it would be different, and it doesn't appear to be different; it appears to be pretty much the same. Before, corporations were saving for defined benefit plans; now it's people saving in 401(k) plans. ... But I had the impression we were going to be ahead if people saved for themselves.

American workers enter the workforce totally financially unprepared. They don't understand compound interest. They don't understand saving. ... It takes a number of years, even in an employer plan where the employer is diligently educating people, for them to understand and appreciate that they have to save money and put money aside for retirement. We are talking about maybe a generation or two of education from all of our institutions. The employers certainly are part of that program, but we need the schools to change and teach people. We need the government, policy leaders, to use the bully pulpit and tell people about this. This is a different kind of world than the one that young people's grandparents grew up in, and they are not prepared right now to do that. ...

The second thing I would have expected would be that, as people got excited by the chance to run their own retirement, ... the coverage of retirement plans would expand. And yet my understanding is ... that roughly 50 percent of the workers in America now participate in some kind of retirement plan. It's the same figure, give or take 2 or 3 percent, from what it was 25 years ago.

... We started out with relatively few people. We had some terrific ideas. We have a great government program, but we're learning how to do this. ... There was an expectation in the late 1980s, the early 1990s, that if we gave people choices, if we built them a wonderful structure, we gave them great investments and daily evaluation and Internet access, that there would be a rush to taking advantage of these programs: "If we build it, they will come." ... I think what we have learned is if we build it, some will come, but some won't.

A lot.

A lot won't. So I think the thinking is being reappraised, and companies -- at least companies who are interested in reaching out to their employees -- are saying, "We need to actually act for the employees." ... We are moving from a system in which if employees did something, good things could happen, to one in which if employees do nothing, good things will happen. We're moving ... to begin ... automatically enrolling people in the programs, to automatically escalating their contribution rates so that you get them to an appropriate savings level over time, to investing the money for them. ... The system is basically being refocused and redesigned. ...

When we talked before, we talked a bit about what a median worker would have to have in a 401(k) program at the time of retirement, say at 65, to take the traditional Social Security retirement age. Do you remember what that figure was?

... To be really safe, we recommend that you shoot to have in all your assets -- this isn't just investable assets, but all your assets -- you need to probably have 10 times your final pay, and that will pretty much carry you through. So if you're making $40,000 when you retire, you probably want to have $400,000 in assets. ...

So if you take a worker who's worked 20 years, what do the worker and the employer together have to put together every year?

If it's only a 20-year period, you're looking at a substantial contribution rate; you're probably looking at 15 percent [of pay]. Remember, this is conditioned on returns. We use 8 percent [return] as our calculator in that regard. ...

Let's take it [to] 25 years [of saving]. What have you got to do then? How much do you have to put in?

You're moving the number down because [of] compounding. You're down to 12 [percent of pay].

What percentage of the workers in America in the private sector today are putting away 12 percent?

... I would estimate that maybe 20 to 25 percent of workers are putting 12 percent away.

So we've got a lot of people who are not doing enough. What are the actual balances we're seeing?

There's two [measures]. One is the average account balance; one is the median. The average account balances are actually getting fairly healthy. There are, depending on what numbers you use, probably $50,000 to $60,000 in an account. The median balances are probably between $20,000 and $30,000.

What are the average and median balances for people between 55 and 65?

They are higher, but they're not that much higher. The reason is because most people haven't been in the system that long. We talked about the real explosion in the system is in the early '90s. These people haven't been in the system long enough to take advantage of that long-term compounding. Let's face it: Older baby boomers never really participated or had an opportunity to even participate in this system, so they're faced with a challenge. They are really going to have to put the savings pedal to the metal, and that's why we have special programs so they can contribute more to the programs and stuff. But they weren't in the system long enough. The defined contribution system will work beautifully for the younger workers who are in and saving even a reasonable amount in their 20s and 30s and getting off the ground.

But I just don't understand how people can seriously talk about thinking about retirement in their 20s and 30s. You have to save to raise your kids. You have to save to buy a home. You're needing to buy a car. ... You may be saving for your college education. You can be a serious saver in your 20s and 30s, but the notion that some of that money is going to be headed for retirement prior to age 40, it seems to me, is a wholly unrealistic expectation. ...

You're correct that it is very difficult to get those people in the program, but what we find is that if young people are automatically enrolled in these programs, they stay. They don't opt out. You get 95 percent participation. ... There [are] a few companies that started doing this, and they got tremendous participation results.

But is it a realistic expectation? If you've got people who are moving around among their jobs, who are raising a family, who are buying a home, who are taking care of other things, I think the question is, is this a realistic expectation to be the primary vehicle for people's retirement?

Let's put it this way: The defined contribution program and the 401(k) is going to be the only way it happens, so we have one choice, and that's to make it work. There is no alternative --

Nebraska saw an alternative.

State governments have more alternatives than private employers. ... They do not have to fund their programs the same way, so the state can make a promise to its workforce, a long-term promise. The state is a perpetual entity that collects sufficient revenue by raising taxes. Companies have to survive in a competitive marketplace. They can't make perpetual commitments.

But ... look at the Nebraska example for a moment. You said earlier the baby boomers have not been in the program long enough [to] see a fair test of what they could accumulate. That's not the case in Nebraska. It's had a system, both defined contribution and defined benefit, for at least 40 years. ... It has had a mandatory participation program, and it is a mandatory-max contribution program. In terms of what you can do to fix the private-sector program, they fixed it -- in 1964. It's been going on a long time, and their [defined contribution] average balances are under $100,000. That worried the state of Nebraska so much, ... they killed the defined contribution plan for new employees. Doesn't that raise a question about how much people can accumulate when they're managing their own money?

The mandatory contribution in Nebraska I don't believe was all that high --

It's 4.5 percent matched by the state at 7.5 percent. It's a total 12 percent, ... the entire program.

I'm not aware exactly of that calculation. I can tell you that companies where they have 40 years of experience, ... the average account balances are in the very high six figures. ... So 25 to 30 years at 12 percent of pay, [and the average account balance] was $100,000? I would want to analyze the arithmetic. That to me is inconceivable.

Well, it's happened. Part of the problem is that most people are frightened by having to manage their own retirement money, and so ... they put it in very conservative vehicles. And then they maybe get coaxed out at a bad time, in the late '90s, and then they get hit in the early 2000s. We're not just talking about doing this for the financially fortunate and the market-bright; we're talking about everybody doing it. So everybody's got to be good at it.

... Everybody doesn't have to be good at it, because what we're doing is the system is being revamped to change the dynamics. Employers are moving in to manage the money for the employees. You're right: In the late '80s and early '90s the concept was, "You have to manage the money yourself." There was an anticipation that we could teach every American worker to be an investment manager. What we have learned is that's not true.

They're not good at it.

They're not good at it, and they're not going to be good at it, ... certainly not in this generation of workers. ... So what do we have to do? We have to address that. Companies are addressing that. ... The system is going to where employees do nothing, and good things happen. Money is going to be taken from their paychecks and put into these programs, and then it's going to be automatically invested in an appropriate, diversified program on their behalf. They're not going to have to worry about making an allocation decision or rebalancing or other kinds of sophisticated decision making. The system is changing. ...

If you looked at the whole 401(k) system, what percentage of it is being funded by the employer, and what percent is being funded by the employees, overall?

It's probably about half and half. The typical 401(k) is two-thirds employee, one-third employer, but what people don't appreciate is that a very large number of 401(k) plans include profit-sharing contributions, so there are additional employer contributions into these plans. ...

So it sounds to me that if you move to a system where the employer is, by default, putting employees into the 401(k) plan, determining their level of participation and then managing the money, we're virtually back to a defined benefit plan, except that the employees are footing 50 percent of the bill, and they've got all the risk instead of the employer.

It's very interesting to look at where the system is going. ... We're really going back to where the retirement system as a whole was based prior to 1980, which is back to that it's an employer-driven system. ...

So the love affair with ownership and running it yourself has gone the way of all flesh.

Well, I don't know. I think people still like the ownership. One of the values of defined contribution plans, like 401(k)s, is that people know that that money is there and it belongs to them, and nobody can take that away from them.

Because it's got an account number and it's got a balance.

Right. ... That money is there. It's in their name; they own that money. So the system of ownership is very positive. But the question is, do they really want all that choice? Do they want all that responsibility? What we're finding is they don't; they want the employer to do that for them. That's where the system is going, back to where it was in the old days. ...

The traditional system has risk; the current system has risk. The employee, at the end of the day, is always the one who is at risk, and even if the employee is choosing to say to the employer, "Do this for me; take care of me; make these decisions," at the end of the day, it's the employee who is going to live with the outcome. Even if we move to a totally employer-[managed] system, employees are going to have to be good shoppers when they're looking for employment. I don't think we can expect employees to be premier money managers, but ... employees are going have to be responsible enough to expect and demand that employers provide good retirement programs.

Jack Bogle makes the argument --

I know Jack Bogle.

OK. You know his thinking. The benefits of compound interest, Bogle says, are more than offset by the tyranny of compounding costs; that the longer you save over time, the larger bite the financial manager is taking out of your savings.

... I agree with Mr. Bogle. ... Fees can eat up a lot of your gains. In the 401(k) system, if you're in larger companies, the fees are much lower than any other investable program. The 401(k) is actually the very best way to invest your money that an individual could have. [For] small companies, the fees are going to be retail, but at least the employees are getting the employer match, and the match is certainly offsetting the fees. Employees have more money than they would have if they didn't save at all, but certainly they're not in as advantageous a position as someone who can have an S&P [Standard & Poor's] 500 index fund. ...

Some people argue that 401(k)s are fatally flawed, basically because of human nature. Number one, humans are not good at saving. Number two, they get a chance to take the money when they shift jobs. They take the money, and they spend it. When they finally cash out, they tend to take lump sums. They get taxed. They tend to spend out fast. This is a fatally flawed system. That's the argument.

I don't shy way from the fact that there are flaws that need to be fixed. I shy away from a representation that the system is fatally flawed. Like any other system, you have to make it work, and you have to learn and improve it. ... What we need to do is design the 401(k) system so we overcome those flaws by opting employees into the program, by helping them set their participation rates, by managing the money for them, by providing them with ways of managing the money in the distribution phase. ...

... The 401(k) system itself does not require choice. The 401(k) system is a structure ... that has a lot of moving parts and flexibility. ... There are actually companies that never gave their 401(k) participants any choice. That will probably surprise most people. The chairman of the board of my organization never allowed their employees to invest the money in their 401(k) plan. They let them decide how much to save, but they invested the money, so that the system itself, the structure, is sound. The question is how do we use it, and ... we're learning how to use it better and better all the time. ... The 401(k), 10 years from now, is not going to look at all like the 401(k) today. ... It is not a perfect system, but the structure itself is sound.