- HIGHLIGHTS

- His take on America's initial relief efforts

- Haiti's economy was improving prior to the quake

- The adversarial relationship between the U.S. and Haiti

- What does Haiti need now?

- What President Obama promised him

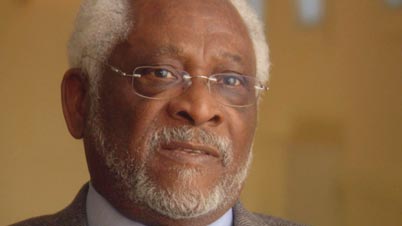

He is the Haitian ambassador to the United States and a former journalist. This is the edited transcript of an interview conducted on Feb. 23, 2010.

I do want to start with the earthquake. That's what brings us here. I'd like to know when you heard and your first reaction.

I heard about the earthquake about five minutes after the fact. Somebody called me -- I was in my office -- and said, "Did you hear what happened in Haiti, especially in Port-au-Prince?" I said, "No." And they said, "Port-au-Prince has been hit by a major earthquake." So right away, I pick up my cell phone and started to call various people that I should get to, like the prime minister's office, the foreign minister's office, the presidential palace. Everything's dead.

And so I called the cell of the secretary-general to the president, Fritz Longchamps, somebody who's also an acquaintance for a long time. I found him, and I said, "What's happening?" ... He says: "This is unbelievable that you find me. The houses are crumbling on the right and on the left. I just parked my car in town, and I'm on foot. I don't whether I'm going to be able to get home, because I have a bridge to cross." And just a few minutes later, [the phone went] dead. And for the next 48 hours, I was not able to speak to anyone in government in Haiti. ...

So at that point, you don't know anything. You know that there's been an earthquake; you know that it's bad. Do you know if the government is standing? Do you know if the president has survived? ...

I have no details. I start listening to the news, and the news says it's a 7.0 earthquake. So I know it is huge, and I know that the epicenter was about zero to 15 miles from the capital. So I figured that I have a lot of people dead, perhaps the leadership of the country.

Then late at night that same night, the consul general of Haiti in Florida, in Miami, Mr. Ralph Latortue, calls to say he talked to the first lady, and the first lady told him the president [René Préval] is all right. ... It would take me another 48 hours before I was able to speak to my own superior, my boss, the foreign minister, and the prime minister later on. It was really a very confusing situation. And we had to do several things right away.

And what was your first impulse?

My first impulse was to -- I'm here in America. The United States is the closest neighbor of Haiti. It's a powerful nation. I have credentials to the United States Department of State and the White House, so I call the State Department, and they invited me right away the next morning.

And I ask for certain things for my country, such as help us control the international airport; help us put together a rudimentary communications system; and help us with a rescue team, especially U.S. boats. I asked for the U.S. Comfort or [another boat]. And they say they were far away from Haiti, but they would be sending some cutters. They indeed did send two initially and then four, with hospital beds onboard. ...

And whom did you speak to first at the State Department?

I spoke to people who were at the level of undersecretary or deputy secretary; later on, with higher-ups.

And they brought you in for a meeting. Was the secretary [of state, Hillary Clinton,] present at that point?

No. The secretary was not even here. The secretary was in Asia on a trip and aborted her trip in Asia to come back to help. But you know, by this time, [it has been] two, three days. The Haitian government officials have surfaced, and they quickly start to put together teams to manage the situation in Haiti. And things move to higher level. ...

Did you have a sense right away that the American response was --

I felt that the Americans were really great in their response. And they dispatch [these] [United States] Southern Command [USSOUTHCOM] people in Haiti with heavy equipment to clear the roads, because the major arteries were blocked. And that's the reason why aid that started to flow into Haiti soon after the earthquake could not move out of the airport.

And we started to hear a lot of criticism, a lot of things happening and [things like], "The airport is clogged, and nothing is getting to the people?" But nothing could get to the people with the roads blocked as they were. So that was the big job of the U.S. Army, clearing the roads.

And then I asked to use the helicopters to ferry food, water, medicine to areas outside Port-au-Prince that were hit. And they did that. In fact, there was a time when they were dropping foods, and I suggested that that may not be too good, because only the strong get it. So they began setting sites to reach the areas and do a distribution more orderly. But they've been cooperating all the way. ...

It sounds like you got, as far as your general assessment of the response, what you were looking for, what was necessary.

I definitely think so. And as I said, despite the criticism, you can never do enough good. And for people who are suffering and who are disoriented, who are confused, everything should be done right away. We could not do everything right away. But we did as much as could be done right away.

There's criticism about the bottleneck at the airport that you were mentioning. The other criticism you heard a lot was that the government was absent. When did you reach President Préval?

As I said, by that evening, the 12th, our consul general was very in touch. I don't have to reach President Préval directly to get things done; I got to his secretary-general within half an hour. And as I said, President Préval himself was in shock. ...

Did you speak to the prime minister, [Jean-Max Bellerive]?

Yes, later on. In the first two or three days, no one could be found.

Chaos.

Yes, chaos.

There's a sense, in the American media at least, that the Haitian government was unable to mount sort of a presence to reassure the country and so on. Did Haitians feel that, or is that an American idea that we're projecting onto Haiti?

A lot of Haitians have criticized the government, but I always bring this up: What do you think it would be like if a city like Washington, D.C., woke up and the White House is flattened, the Congress is flattened, FBI, CIA, the banks, all the banks, all the communication system flattened? ...

You would not know how many died. Of course, this is a big country. ... But I don't think your leadership in Washington itself would have been able to jump up right away. Well, that's what happened to Haiti, a country with a feeble infrastructure, with feeble communications system. I ask people to be a little bit comprehensive and try to comprehend what happened in Haiti.

This was a country that even before the earthquake was struggling -- not much room for error, maybe. And then to have a disaster hit [like] this. I wonder if you could give me some sketch of Haiti before the earthquake. What was the country that was hit so badly?

Haiti had just begun to come from under years of mismanagement. I came to Washington here in 2004 with the interim government. When I arrived here, we only had 2,500 policemen and policewomen for the whole country of 8.5 million people.

And the Haitians didn't kill each other. Compared to New York City, with a population of 8.5 million people, you know, they have 45,000 policemen, policewomen. Since 2004, we have put in place a program of bringing security forces Haiti. And we have beefed up the police force to 10,000. It's supposed to go up to 14,000 before President Préval leaves in 2011. And I don't know whether that's going to happen.

However, with that kind of a situation, Haiti began regaining its composure, so much so that in August of 2009, just a few months before the earthquake, I went to Haiti on vacation, and I did not go as an official.

I put a hat on so they won't recognize me, because my white hair gives me away. And my friend picked me up at the airport, and we went around. I wanted to gauge the level of security in the country. ... We were out [at] 3:00 in the morning, and we find people on weekends -- Friday, Saturday -- out all over the place. So by that time, I say, "Oh, yes, security has come back." We were stopped by the police a few times, and they politely asked for our papers. And they were very apologetic that they stopped us. They didn't know who we were. And I said, "I'm glad you're doing your work."

So this was a Haiti just coming back. ... I'll give you another example on tourism. The tourists had fled Haiti long ago. And even the [tourism] was stopped in Haiti on cruise lines like Royal Caribbean in the northern part of Haiti. They used to go to a place call Labadee. ...

Well, the first week of December 2009, Royal Caribbean inaugurated a $50 million pier in northern Haiti in Labadee and had arrived that week with about 5,400 tourists. The first day before the earthquake, The Miami Herald published a major piece [about] the hotel boom in Haiti. And even on [PBS] the Monday before the earthquake, [they] had a major story [about] how Haiti was ready to enter into the development.

Since we got here, we came with a slogan and a program. The slogan was, "Haiti is open for business." And we work with Congress. We got the HOPE [Haitian Hemispheric Opportunity through Partnerships Encouragement] Act passed by the Republican Congress in 2006, and then enhanced by the Democratic Congress in 2007, we got a HOPE Act for 10 years. And HOPE opens up the U.S. market for Haitian products, especially textiles and apparel, coming here duty-free. And it's for 10 years with fewer restrictions -- almost no restrictions -- from the HOPE Act we had in 2006.

That HOPE Act already created 25,000 new jobs in Haiti. And the reason I came with the idea of "Haiti's open for business" is because I think jobs is what we need to help that place, where 70 percent of the people were unemployed. So, in short, Haiti was a country coming out of a long dormant stage and entering in a development stage. And then we got hit.

So Port-au-Prince was a city that had become too big in a bad way. It was a monstrosity -- a city of 2 million which was built for 150,000 in the 18th century. So back in 2004, I even wrote about that, and I said Port-au-Prince was an ecological catastrophe waiting other happen, because I saw this place was just ready for a big hurricane that would have washed away all these flimsy abodes from the hillsides. I didn't see an earthquake.

But there were storms. There were these storms in 2008, these terrible hurricanes. Maybe you can describe for me not just Port-au-Prince, but what was the impact of those storms?

The impact [of] those storms was that it, according to the president of the World Bank, made some damages of $1.2 billion. And people expected Haiti to explode after those hurricanes. But Haiti did not explode. That's another thing that I wanted to bring out.

The Haiti before the storms had reached political stability. Because President Préval was elected in 2006 with 51 percent of the vote, [he] turned around and embraced people from the 49 percent that didn't vote for him, and brought them in the Cabinet. ...

So for the first time in Haiti we were coming back to the idea of "In unity there is strength." That's how we won our independence. So I thought, well, for a man who's very shy, the president has been working behind the scenes to bring stability. So, four hurricanes and food riots in 2008, people expect the government to collapse. Didn't collapse. And we had two changes of prime ministers. And people, always, when you have change of prime ministers like that, think the government is going to be dislocated. It didn't happen. Political stability had been reached, and we were on the threshold of going to the next step: economic stability.

One thing we've heard is a narrative from the international community's side, that the storms provided a moment where [Ban Ki-moon], the secretary-general of the U.N., in fact sees what's happening in Haiti and says, "We need to do more to help in this progress that you're describing, that since 2004 there has been improvement, but that the international community could do more." It produces Bill Clinton as a special envoy. There's a whole mounted campaign. Did you observe that as part of this progression toward new stability that the international community was doing more and more effectively?

In fact, I keep talking about this silver lining. I say it's really sad that it has taken a catastrophe of major proportions to have the whole world -- I really mean the whole world -- focus on Haiti, because Haiti deserves it. Not because I'm a Haitian I'm talking like this. But in 1804, when Haiti became independent, there were only two independent countries in the Western Hemisphere: the United States of America and the Republic of Haiti.

And of the two, one stood for the liberation of all people, and Haiti worked to help others. By defeating the 40,000 troops of Napoleon in Haiti, we helped the United States get the Louisiana Territory. By defeating the troops of Napoleon, we stopped their conquest of America. And we helped Simón Bolívar to go down to Gran Colombia and liberate Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador. And then the movement just picked up steam in the rest of South America.

So can you imagine this little country that people keep calling the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere was the seed of freedom and the seed of wealth for others? And just by -- I don't know what you call it, whether it's nature; some people would say it's God that did it. Everybody is saying, "Oh, well, let's look at Haiti now, and let's do something to help Haiti."

Can I ask you to tell the story of the Louisiana Purchase in a little more detail?

... In the American history books they do talk about the Louisiana Purchase. But imagine what happened: A slave revolt starts in Haiti in 1791, and then there's guerrilla warfare going on. And before that, before Louisiana Purchase, we sent some of our Haitian soldiers on the French command in 1779 to fight in Savannah, Ga., and they learn a few things about how you fight. They come back to Haiti, and with others, they start the rebellion.

The French find out that they might lose their wealthiest possession. Haiti was much more wealthy at the time than the Louisiana Territory, all the 13 states. The capital of France in the Western Hemisphere was in Cap-Français, which is today Cap-Haitien. Pauline Bonaparte, the sister of Napoleon married to [Gen. Charles] Leclerc, had a mansion in Port-au-Prince, just to show you that Haiti was the center of opulence, the center of power. And from Cap-Français, the French control Louisiana.

So by 1801, they feel their control is getting loose. So Napoleon decides to stop this rebellion, and he sent 40,000 troops to Haiti. But, you know, at the time, Haiti had only 450,000 to 500,000 inhabitants, including 30,000 Frenchmen and 30,000 mulattoes, and the rest are blacks. So why do you send 40,000 troops to squash a little rebellion like that? That was not the mission. The mission was going on to the northern territories -- Louisiana.

So we [the United States] help the French down in Haiti. We defeated them there. And when the French found out that the Haitians were going to succeed, on May 18, 1803, when all Haitians got together -- there were roving bands fighting the French here and there -- in the place called La Caillère and decided that they would adopt one flag by pulling out the white from the French flag and getting the red and blue together, and by having one motto: "In unity there is strength," the French backdated to April 30, 1803, the sale of the Louisiana Territory. That's 13 states west of the Mississippi from the Gulf of Mexico to the border of Canada, all the way through the Rocky Mountains. Sold it for $15 million, 3 cents an acre, the biggest real estate deal. That's what Haiti did for the United States of America.

However, it was, quote/unquote, "a bad example" for black slaves to arise against their white masters. So the United States back then slapped an embargo on Haiti to bottle us up. And they did. And it remained for 60 years. It was [President] Lincoln and Frederick Douglass that changed that.

Haiti did help also with the liberation of South America, as I said before. But what happened? In 1823, at the first Congress of the Latin Congress in Panama, Haiti was not invited. [You could not] invite black folks, former black slaves to meet your international congress like that, you know. That gives bad ideas to other slaves in the South of the United States.

So I understood, and I'm quite sure people now understand, if Haiti is poor today, you have to go look back at the beginning. We didn't get our independence just like countries in Africa or in Asia or even in the Caribbean in the '50s and '60s when the Soviet Union, China, European Union and the United States were rushing in to help solidify them. No. We got our independence, the first one [to] rise up against slavery. And we paid a steep price for it.

Do Haitians feel that they're still paying the price for that?

I don't know whether we feel we are still paying the price for what we did back then. But initially, starting the way we did, the remnants of the ostracism still stay with us. And the catastrophe that happened in Haiti I think may be the breaking point where people come in and say: "Oh, you mean the Haitians did all that? How come we did not know? And why did we act the way we did with them in the beginning? Perhaps now we have to change and work with them, because they did something good back then."

... I wonder if you could tell me, from a Haitian's perspective, how do you make sense of American policy in Haiti? ... I guess what I see happening is periodic meddling over and over and over again. ...

Yes, I have to say that the adversarial situation between Haiti and the United States began from day one of Haiti's independence, because the U.S. could not afford to have a slave state form a [free] state next door while they have black slaves in the South. So they tried to contain Haiti from day one. Then, later on, [it] goes further. By 1915, the U.S. invades Haiti and stays there for 19 years. And during those 19 years, I say the U.S. reinforced the colonial system that was there by working mainly with Haiti's elite, mainly light-skinned elite, against the masses.

And that's what gave rise to anti-Americanism and gave rise to people like [former Haitian dictator] François Duvalier and the school of black power, that was called. And finally, in 1934, [President Franklin D.] Roosevelt saw to it that the invasion, or the occupation, ended.

However, by leaving Haiti, the U.S. had reinforced what I consider the system that had been detrimental for the country from day one. And even when the U.S. tried to help Haiti with "democratization" in the 1990s, when 23,000 U.S. troops went back to Haiti, ... again, the U.S. did damage Haiti before that by accepting to declare an embargo on the country. Of course they demanded the requests of the then-president of Haiti. I had fought against that. I wrote against that. I said, "Look, if you declare an embargo on this little country, it will take us 15 to 20 years to come back to the position where we were."

People didn't listen to me, because they had to bring back democracy. And you bring back democracy by any means, and the means they were going to bring back democracy was to [impose] an embargo. Reminds me of the embargo that they declared early on in Haiti's history. So we have to be very careful when we want to impose a way of life on other people.

You have an embargo in 1990 and then another one in 2000. ... It's the first President [George] Bush [who] enacts an embargo in support of President [Jean-Bertrand] Aristide, ... and then the second President [George W.] Bush enacts an embargo, at least [as] an aid rupture, to pressure Aristide. ...

If Aristide is the one who asked for an embargo against his own country, I suppose that the people that he worked with think it's good to put an embargo on Haiti. And I'm saying that we have to stop this idea of embargos for political reasons. We have to look at the people. Very often when you impose embargo, the politicians and the big boys of commerce don't get hurt. They know how to go around that. It's the people who suffer.

So the embargos were devastating?

Definitely. ...

Explain to me the problem presented by the dominance of NGOs.

Because of the problem of corruption in government, lack of transparency in the past, the international community has decided to work with non-governmental organizations, like the NGOs. And Haiti had become sort of a haven for NGOs. In fact, they call Haiti the republic of NGOs. [There are] about 10,000 of them, all sorts. We don't know what they're doing.

And now, what they used to accuse government of, it's been turned against NGOs that are not regulated, and we don't know what they're doing with the money.

NGOs cannot build the infrastructure of Haiti. They cannot build the roads, the electricity, the water system and so forth. So I've been pleading with international organizations with some success -- not with the U.S. government, USAID [U.S. Agency for International Development] yet -- to work with the Haitian government so that they cannot continue to say the government is too weak.

I think it should test us, because we put in place anti-corruption programs, and we're more transparent now. So while I'm not speaking against NGOs, who do some good work in education, in health and so forth, I'm saying at the same time we have to work with the Haitian government to strengthen it so that we don't keep repeating the same thing, you know, with the catch-22 -- we cannot work with them, they're not transparent, so we work with NGOs. NGOs cannot do all the work. And so you keep going and going. We have to trust the government and test them and go forward. ...

What does Haiti need now?

I think Haiti needs a ... group of people that are going to work together and present a coherent plan, which will include the Republic of Haiti and not the Republic of Port-au-Prince, because I think that has been the big problem in Haiti: everything concentrated in one place, one capital. And when I say the Republic of Port-au-Prince, people used to talk about it that way. Now, the future is ahead of us. If we're going to create the Republic of Haiti, that means to develop the provinces. That means creating new cities, regulated. And if we need -- if we must -- rebuild Port-au-Prince, rebuild it according to codes and streamline Port-au-Prince. That's what I think Haiti needs.

And Haiti needs to rebuild its agriculture, because at one point, Haiti used to feed the whole Caribbean. Haiti needs to reforest, because right now we're only 5 percent forested, whereas when [Christopher] Columbus arrived in Haiti in 1492, it was more than 95 percent forested. [This is] but another story, how the deforestation of Haiti began, with all the precious wood of Haiti going to the major cathedrals in Europe with [this] program of deforestation, people cutting it down for wood. ...

I wanted to ask about what you described, rebuilding it. It will take money. There was a donor conference in April 2009. Hundreds of millions of dollars were pledged. We were told by the time the earthquake happens, a small fraction of that money has actually been disbursed. More donor talks are coming; more money is going to be pledged. What is your assessment of that process, and are there steps that can be taken to make sure the money actually finds its way into Haiti?

When Secretary-General of [the] U.N. Ban Ki-moon named former President Clinton as special envoy to Haiti, I say good, because President Clinton is, I think, the personality [who] has the leverage to get this money flowing.

And when people in Haiti, some Haitians, talked about, "Oh, we have a new emperor," and they wanted President Clinton to get involved with internal politics, I said, "No, I don't think that's his role." I think his role is going to [be to] work with the international community, work with businesspeople to get the money unblocked, because too often we hear, "Haiti got so many billion dollars," and we never see where it goes; we never see where it's coming [from]. So I think this time, with the pressure of the international community, with somebody like President Clinton involved in Haiti, and with the secretary of state, his wife, Hillary Clinton, having a stake in Haiti also, and putting a team in place to work on that, I expect to see the money flowing this time.

One of the problems in the past, as I understand it, is that it's not just slow-moving wheels of the international community. It's that the Haitian state is weak enough that asking for the money and having a place to direct the money is a problem. How do you deal with that now?

Well, the other thing, the real word they used is "absorption." The absorption capacity of Haiti is quite low. The Inter-American Development Bank, IDB, has stated that 83 percent of Haitian professionals are abroad, mostly in America and in Canada.

I think if we really want to help develop Haiti, a program should be instituted to bring back quite a few of our professionals, and then people won't be talking about the low absorption level of the Haitian government. In fact, the IDB, Inter-American Development Bank, has a program where it is enticing some of [these] professionals [to come back].

Something else that the Haitian government has to do: Once a Haitian leaves the country and accepts another nationality, becomes citizen of another country, he's cut off, has no rights in Haiti. Well, President Préval has been pushing a change in the constitution of Haiti. ... Once that is done, you will see the Haitians in diaspora coming back to the country to help. I believe the future is bright in that sense. ...

We've talked about responsibility. Is the imperative to get Haiti right, is it really a moral obligation for the United States, or is there a practical element as well?

I don't think it's only moral. I think if the U.S. wants to work out of self-interest, it would be good for it to help Haiti get on its own feet, because the closest place to Haiti is Miami, for the U.S., [less than] 800 miles away. Whenever things start going bad, the Haitians take to their boats. I don't think it's a pretty picture for the U.S. Coast Guard fetching people from the sea and taking them back and for you to be having all these things on front pages.

So, out of self-interest, the U.S. decides: "OK. We're going to keep them in their place, at home. And to keep them in their place, at home, let's have jobs for them there. Let's help them with the industries. Let's have investment."

I think the time has come for Haiti not to be looked upon as a charity place where we come in with foreign aid, and helping the people with the schools and things like that. ... We should help Haiti with investment because Haiti has created the situation for investment. That's why Bill Clinton went to Haiti in October with about 150 businessmen and businesswomen: to look at opportunities. ... And that's why I encourage my government to refurbish all the fortifications that Haitians have built in the 1800s to resist French encroachment.

You hear about the Citadelle Laferrière, the big fort on top of the highest peak. ... Let's refurbish them. Let's build bungalow-type hotels around them, and let's invite the foreigners. Let's invite the black Americans to come see what their brothers and sisters did over 200 years ago. They will be amazed. They'll come back, and they'll tell the [story] of Haiti, and Haiti will become a Mecca.

That makes sense. And I want to believe that that makes sense. But on some level, that's before the earthquake. That's before the destruction that the investment was returning. Isn't this just a brutal setback?

The earthquake happened on one-fifth of the island. Four-fifths of the island [were] not touched. It happens that the tourist development that the minister of tourism started with was in the north of Haiti. It wasn't touched [by the earthquake]. ...

San Francisco is a big U.S. city that is sitting on a fault line. And San Francisco had been hit more than once. And people continue to invest in San Francisco. Why not in Haiti, which had been hit with an earthquake only three times now: once in the 1800s, late 1700s; Port-au-Prince in the early 1900s -- Port-au-Prince was hit before; and now, 100 years later. I'm quite sure there's room for investment.

Let me ask this: Does the earthquake, in your mind, reveal anything about Haiti, about the world's involvement in Haiti?

... Again, part of the silver lining: The earthquake has allowed the world, the whole world to see Haiti as a place where it all began in this hemisphere, where freedom began in this hemisphere. And freedom, to me, is very important. When you have free men and free women taking their destiny in hand, it can do wonders, as they've done wonders in this whole [Western Hemisphere]. ... The whole world stops to think, because of the earthquake, that Haiti was instrumental in helping [build this hemisphere]. The whole world will say Haiti deserves better.

The earthquake brought Haiti back in the world's eyes, actually. ... Do you worry when the cameras turn off?

No, I don't worry when the cameras turn off. I don't worry when we [fall] off the front pages, either. And I'll tell you this: President Obama, after he had addressed the ... the nation on Jan. 27 [for his State of the Union address], met me for a photo op and gave me a handshake. Strong handshake. And he said: "You know, someday cameras will be off Haiti, and you'll be off the front pages. But I want you to know, I want Haiti to know that we are with you for the long haul." So I expect Haiti's friends throughout the world to be with us for the long haul. And I will see to it that Haiti is kept in front of people, at least ... where I work.

That's the reason why I've become sort of a lecturer. Go to universities; go to the churches; go to the clubs; go everywhere to keep Haiti in front of the people. And when cities, when universities, when churches get to be partners of churches, universities, schools in Haiti, I think we will keep the Haiti story going.