- HIGHLIGHTS

- Why his experience on the ground in Haiti was the "most heartbreaking"

- On being unable to provide adequate food and water weeks after the quake

- What could the U.N. have done better?

- Why he's optimistic about Haiti's future

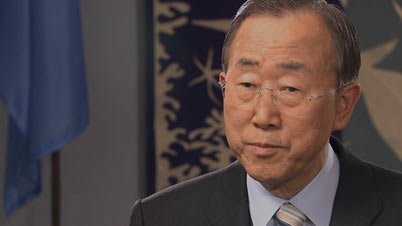

He is secretary-general of the United Nations. This is the edited transcript of an interview conducted on Feb. 12, 2010.

Secretary-General, let's begin with where you were when you got the news, how you received it, and the impact it had on you as you learned what had happened.

I was coming back from a retreat outside of New York on that day. While driving, I was informed by our senior adviser that Haiti was struck by a 7.0-magnitude earthquake. Immediately I cut off my car. I have communicated with our senior staff, and I have spoken with President Bill Clinton and the U.S. ambassador and Haitian ambassador. And all of our senior staff had to spend overnight.

Next morning we convened an emergency-staff strategy meeting, and we decided to immediately dispatch [Acting Special Representative of the Secretary-General and head of the U.N. Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH)] Edmond Mulet. We decided to dispatch the best and most capable team to the ground. That's what we did.

Immediately we began to talk with the U.S. administration. I sought immediately the helicopters and other logistics and food and the water.

Of course we had to communicate with all member states, and I reported to the General Assembly in the afternoon. In the morning I went to Security Council, reported to Security Council members. That's what I did right after the second day.

How soon were you able to talk to somebody on the ground at your headquarters?

We were able to speak with the people on the ground through our videophone. That whole communication had been locked down. I understand that the U.S. had only one working communication line, and United Nations had fortunately had one line, so we were able to speak with people on the ground. ...

When you arrived on Sunday afterward, you were down near the palace, and people were shouting; they were asking for aid. Tell me about that for you. ...

I have seen many such disasters at stricken places, starting from tsunami [in the Indian Ocean in 2004] and Sichuan earthquake in China [in 2008] and Myanmar hit by Cyclone Nargis, [also in 2008]. But my experience on the ground in Haiti was most heartbreaking. That was saddest and most troubled experience for me.

I met many, many young men and women just wandering aimlessly in front of the presidential palace, which [had] just collapsed. They were shouting to me: "We want food, water. But most important we want job, job, jobs." And that's what's quite striking to me.

And that is why we initiated immediately "cash-for-work." By providing $5 per person per day, we have now employed more than 35,000 young men and women to a daily job. That was a very immediate and creative initiative which we have taken.

On that trip, on that Sunday, you also met with Mulet?

Yes, I did.

There was a lot of criticism by then about the failure to be able to coordinate the aid. What did he tell you?

First of all, his eyes were full of tears, having seen all of our senior staff were killed, and many of our staff's fate were not known. They were all caught under the debris of destruction. I also was crying inside my heart, and what he told me was that this has created great logistical problems.

Considering the extent, the magnitude of this disaster, I think United Nations has done maximum what we could do at that time under the limited capacities, limited logistics. Of course there were some confusions, but that you should understand as a matter of reality. But from the day when I was there, we had already established much better-structured and very efficient coordination with the United States and Canada and Europeans and other NGO [non-governmental] organizations.

Now, I think we should be very proud of what we have been doing. I'm very proud of our U.N. staff. Even during the absence of leadership and even with such a tragic loss of our staff, the United Nations staff immediately carried out their duties, day and night.

There's no doubt that you were hit very hard and that you were, in a sense, among the key first responders. ... When I talked to Edmond Mulet, he said that he couldn't have coordinated all the aid, that it would have slowed the aid coming in.

There was a logistic and infrastructure which have been all knocked down, and there was no road or no port. The airport was very much limited. The control tower was damaged. With only American military forces providing and taking some operational capacities at the airport, we were not able to have speedy delivery of the humanitarian forces and goods.

That was what had happened during the first and second and third day. From then on, I think were able to, first of all, establish five land corridors to Port-au-Prince. The airport was operating smoothly, even with limited capacity of landing and departure. And I have spoken to President Obama and Secretary of State [Hillary] Clinton that U.S. should repair the damaged port facilities. That is why United States has brought the 14 dock facilities. That helped a great deal. ...

... One of the tensions was between the United Nations, between you and the United States military over the inability to get aid supplies in and landed at the airport. Can you tell me about that tension that you had with the U.S. military over the airport?

I do not know [of] any such a criticism that there were tensions between the United Nations and United States. First of all, we were mutually reinforcing, complementary. As far as security and rule, law and order were concerned, the minister was in charge, and U.S. military forces made it quite clear that their role was to help facilitate smoother delivery of humanitarian assistance.

Did you need the United States to do that, or [did] that in some ways, as some people saw it, it undercut the United Nations? You had 3,000 troops on the ground. You had an able military force there. You could have run that airport yourself. Why did the United Nations cede control of the airport over?

Of course we have 3,000-man-strong minister forces in and around Port-au-Prince. But if you consider the magnitude and extent of damage as well as the capital itself, including the office of the president and 11 ministries out of 13 government ministries, they were all destroyed.

And at that time, the government was not able to function properly. Under that circumstance, I think the immediate available support came from the United States with their logistical capacity, with their oldest resource capacity, and also United States, which really did a great job but in very close coordination with the United Nations that I really appreciate.

Now, after two weeks or so, I have asked the President Bill Clinton to have an added role to coordinate international aid, because there was certain difficulties and criticism for the lack of effective coordination. And now on the ground, Mr. Edmond Mulet has created a very well-functioning framework of coordination with the president and prime minister and American ambassador and also with the Canadian forces. …

In the United Nations and back here, we coordinate with all the member states, particularly the United States and other key European countries. Now I think we are now able to provide 2.3 million people daily food rations, and almost 1 million people we provide drinking water.

There was a statement that you made that by the end of the second week that you wanted to provide 1 million of the people who were in need of food and water out of the 2 million who were in need. ... You got to about 600,000 by that time. What was holding you back? Why weren't you able to move faster?

I said that within two weeks we'll be able to provide food to 1 million people and after two weeks we will be able to provide 2 million.

But after two weeks you got 600,000, right?

You should understand that there was a level of logistical support, and infrastructure was totally damaged. And even the land access from Santo Domingo, [Dominican Republic,] to Port-au-Prince was heavily congested, and port facilities [were] not that immediately repaired.

You talked in one editorial about unplugging the bottlenecks. What were the key bottlenecks for you? The land bridge from Santo Domingo is one.

First of all, the airport was heavily congested, and road access from Santo Domingo again was heavily congested. The port facilities were all damaged, with only 14 landing facilities. I think we were able to have some better access.

I sat down with Kim Bolduc, who was a head of your humanitarian aid program there, and [she said] two and a half, three weeks after the earthquake, you'd only reached 45 percent of the population with food and water.

Overall, 3 million people have been affected, and almost 80 percent of houses or homes were either completely destroyed or unsuitable for life. Therefore, the magnitude was just unbelievably unbelievable. Therefore, I think we have done our best efforts under such circumstances. And this is what we have shown, the best ability, best face of the United Nations. And I'm very proud of and grateful to the whole international community.

Looking back, is there anything you could have done better, do you think?

Now, first of all, we have been talking always with great emphasis on disaster-risk reduction. This is one of the high priorities of the United Nations. In addition to providing immediately humanitarian assistance, this is always lessons which we learn only after disaster [has] struck us.

Now, United Nations will continue to build up and strengthen disaster-risk-reduction capacity. First of all, when we rebuild Haiti, then new structures, new buildings should be earthquake-resistant or hurricane-resistant. We are now very seriously looking at the possibility.

Were you aware that this was an earthquake-prone area prior to Jan. 12?

... Personally I was not that much aware of that.

Had anybody looked at the building that the United Nations was housed in?

We had checked all this security concern. When we rented this U.N. headquarters building, there was a concern raised by the expert, and we made all the necessary measures to strengthen our safety and security there. But the magnitude of a 7.0-scale earthquake [was a] disaster to our headquarters unfortunately.

Is there any one thing that you can say now that you've learned from this experience that would change the way you approach the response and the relief effort that you made?

First of all, effective coordination and immediate humanitarian assistance, that should be more effectively coordinated.

Why wasn't it more effectively coordinated then?

There's a whole capital [that] was hit, and there was no functioning government. And even United Nations was hit, and we lost 94 [of our] best staff at that time. ...

I understand. It was a huge blow. And you lost people that I'm sure were friends of yours. But if, in looking back and trying to understand what you could have done better, you're saying that you could have done a better job of coordinating and organizing the response, I'm wondering where you think the weak point was in your preparation?

When I have visited all this earthquake [in] Sichuan and tsunami and Nargis in Myanmar, there was a functioning government. Whole leadership were able to concentrate on mobilizing their nationally available resources and implements.

Right. Like in Pakistan, it wasn't Islamabad that was hit.

Yeah.

But you're saying that because of the nature of this quake and its location, there's nothing you could have done better?

There was very limited access to the place, and that is one thing which really hampered the urgent and immediate and effective access by the international community. ...

I think the international community reacted very swiftly and properly. It is quite moving that there were 50 search-and-rescue teams immediately, almost within two, three days' time. There were 1,800 people working day and night to rescue people. We have rescued more than 200 people. We need to be proud of what we have done. Of course we have to learn continuously the lessons learned from this disaster. ...

I did hear from the people of Haiti consistently that they were impressed by the response of the United Nations, the United States, the NGOs. They held their own government in not such high regard.

But now I can fully understand the frustrations and sometimes anger by the Haitian people [regarding] their late delivery of assistance. But we have done our best. Now, as we are moving from this urgent, immediate, early recovery and assistance, [we are moving into] a phase to begin a long-term reconstruction.

... Was it a frustrating time for you?

I wouldn't say it was a frustrating time. It was a very troubling and heartbreaking experience for me as a secretary-general. Now, my concern, my priority, was how effectively, how quickly I can provide and deliver all these available [donations] which have been pouring from the international community to the people in need on the street, and how much shelters we could deliver to those people. That has been always in my mind, in my heart.

That must feel like a tremendous burden at the time.

Tremendous burden. Tremendous burden. Yes.

I can only imagine. You say you're optimistic about the impoverished nation's future. Why?

When I became secretary-general, I knew that Haiti was one of the poorest countries in this hemisphere, and I visited on my own on the first year. And I had very good meetings with President [René] Préval.

And then next year, again, after having appointed President Bill Clinton as a special envoy for Haiti, we both went together to discuss with the Haitian people how the United Nations and international community could help Haiti to first of all boost their national economy, domestic economy, and how we can attract foreign investment, how we can make Haiti attractive for investment. On the basis of this strategy, I think the Haitian government was making a very good progress toward job creation and also export to foreign countries, particularly United States.

You may remember that United Nations had [tasked] Professor Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia University and the British economist Paul Collier ... on two different occasions to provide us a strategy project. On the basis of this, we were moving on. With this disaster I think they went back to square one. Unfortunately, we have to rebuild back a better Haiti.

I spoke with Professor Sachs. He said that during 2009 there was a lot of nice talk and a lot of promises being made, but very little real investment was made, and that progress was hard to perceive. ...

When I, together with the president of Inter-American Development Bank, Mr. [Luis Alberto] Moreno, convened international donors' conference in Washington, there was quite wholehearted support from the international community. Of course, here you see the reality. ...

But with all this support, the Haitian government and United Nations together with President Bill Clinton are moving toward the right direction, good direction. And they were given special legislative preferential treatment by U.S. Congress called HOPE [Haitian Hemispheric Opportunity through Partnership Encouragement]. They were able to export … duty free. So it was some very good incentive for Haitian industry, and with that they were attracting many foreign investment.

What kinds of foreign investment was being attracted?

Mostly textile industries. And Haitian government was providing all these good incentives to foreign investors.

Can you give me an example of a large foreign investment being made in Haiti in 2009?

There were many small, medium textile industries, even including from my own country, Korea. I met Korean businessmen while visiting Haiti. And there were many other foreign textile business industries working there.

How much in dollars? Do you have any idea?

I do not have any idea in dollar terms, but it was doing very well. And Haitian people are very intelligent and talented. And one of the priorities which President Clinton and I were focusing [on] was that to prevent some brain drain from Haiti, all highly educated people should remain in their own home country. That's what we have noticed.

And come back.

And we were very much encouraged when we visited a certain educational institute. They were all committed. Then after they graduated, they all volunteered to stay, remain in their home country, to work for their country.

... I have no reason to doubt your sincerity and belief that it's an important country to build back better, as they say. The ordinary viewer, however, the ordinary observer looks at this and says: "A lot of promises were made about New Orleans, and a lot of promises got made about what happened after the tsunami. And in many of these cases, if not most of these cases, we don't see substantial rebuilding once the cameras are shut off and the lights go dim." How do we fix Haiti after the cameras are shut off?

My experience during [the] last month, the support of the international community was unprecedented. The Flash Appeal of the United Nations received as of now unprecedented response from the international community in such a very short period of time. People were just competitively providing and reaching out to Haitian people. ... Then I was able to see hope for our capacity to build Haiti better back.

And when I was in Haiti, I met so many young people, and I found them very resilient. While they were very much frustrated by all this destruction, I found that they did not lose their hope. And the president, Préval, was also encouraging people by saying: "Let us dry our eyes. Now is a time to rebuild our home country." That's quite a strong message.

You wouldn't be in this job if you weren't a pretty hard-nosed fellow and pretty realistic.

Yes, I am quite realistic and practical.

... Now we've got the long road ahead. Realistically, what do you need to do? What's going to have to happen to make sure that things actually do change in Haiti?

The most important thing would have come from the Haitian people and their leadership. You have seen what has transpired during the last many, many years starting from all these dictatorial regimes.

It's still listed as one of the most [corrupt] regimes on the planet.

That has prevented their growth politically and economically. Now we hope, of course, good governance, strong leadership and unity of their people, that will be very much important to rebuild their country back for the better future.

It's a hard road ahead?

Of course it will be very tough, but they should know that the whole international community now are standing behind them.