He killed his parents after years of abuse, but even some of the jurors who convicted him wonder if he deserved life without parole.

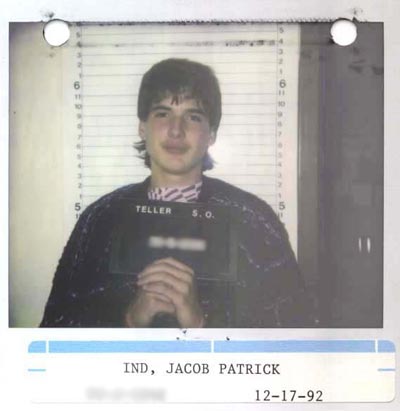

On Dec. 17, 1992, 15-year-old Jacob Ind went to school after a mostly sleepless night. In the early hours of that morning, he had murdered his mother and stepfather, Pamela and Kermode Jordan. He planned to tell a friend about the crime and then commit suicide. But his friend told the principal, who called the police.

According to Jacob's brother, Charles, the murders were the culmination of years of abuse by their parents. Jacob told FRONTLINE that he began thinking about killing his parents when he was "12 or 13" years old. "What basically put me towards the path is I saw no way out," he said.

Even after the killings, Jacob seemed detached from the reality of what he'd done. "I didn't really grasp the permanency of their deaths," he told FRONTLINE. "I definitely didn't understand the gravity of what it means to kill somebody. I mean, I didn't think they'd feel pain. I didn't think that anybody else would be affected."

"I remember I was sitting in the police station -- and this is how out of touch of reality I was. I had a small amount of marijuana, like an eighth of an ounce, in my bedroom. And I'm telling my brother, 'You got to get the marijuana or else I'm in trouble.' I'm arrested for first-degree murder, and I don't think I'm in trouble!"

Jacob's trial began on May 12, 1994. His lawyers argued that he had acted in self-defense, killing his parents to put a stop to years of physical, emotional and sexual abuse. The defense called Jacob's older brother, Charles, who testified that both boys had been molested by their stepfather.

"I did my best as far as explaining to the court the type of environment that we were in, the pain that we were experiencing and being inflicted upon, even the sexual abuse," Charles told FRONTLINE.

Referring to the boys' molestation at the hands of their stepfather, Kermode, Charles said: "He would wait until we got home, oftentimes sneaking up behind me or Jacob and throwing us into the bathroom -- literally taking us by the shoulders and tossing us into the bathroom. And there he would hit us across the face and body and say, 'Get on the toilet,' and he would pull the ropes out from underneath the credenza."

Jacob has kept silent about any sexual abuse he suffered at the hands of Kermode. For him, what was as damaging, if not more, was the emotional battering he suffered from his mother. "That's the one thing I wanted more than anything, was somehow to earn her love," Jacob told FRONTLINE. "I mean, there's times she made it absolutely clear that she hated me, basically. And as a child, that is more hurtful than getting hit across the face or getting beaten."

The defense, however, did not call Jacob to testify on his own behalf, worried that he would do more harm than good. "His demeanor at trial, due to the fact that he was an abuse victim, was flat," defense attorney Shaun Kaufman told journalist Alan Prendergast in 1998. "He wouldn't have been a fabulous advocate. He wouldn't have cried for his parents. He wouldn't have shown any remorse."

Another obstacle for the defense was the fact that Jacob had offered a schoolmate -- a 17-year-old loner named Gabrial Adams who wore military clothes to school and considered himself a martial arts master -- $2,000, which he did not have, to kill his parents while he was sleeping. "It was supposed to be two shots, quick and painless," Jacob told Evan Dreyer of the Denver Post in 2000.

But Adams botched the job, and Jacob, awakened by the gunshots and the ensuing struggle, fired the fatal shots using his stepfather's .357 Magnum revolver.

Attorney Paul Mones, who specializes in defending children who have killed their parents, says that accomplices make defending parricide cases that much more difficult. "When you have somebody come along with you or you hire somebody, ... the arguments that you can make -- that it's solely abuse-driven or the kid had no recourse to get help -- are much more difficult."

On June 17, 1994, Jacob was convicted of two counts of first-degree murder. As a juvenile, he was not eligible for the death penalty; instead, he was given a mandatory sentence of life without parole. (In a separate trial in December 1994, Gabrial Adams was also sentenced to life without parole.)

Mary Ellen Johnson, a Woodland Park author who consulted for the defense, argues Jacob's counsel should have done more. After the trial Johnson wrote a book, The Murder of Jacob, charging that school officials, social workers and both the prosecution and defense didn't do enough to investigate Jacob's abuse at home.

According to Prendergast's article, at least three jurors have approached Johnson or other Ind supporters, saying that more information about Jacob's home life might have swayed their votes. One of those jurors, Patricia Scott, has said that she did not realize that a guilty verdict would trigger an automatic sentence of life without parole. In Colorado, jurors are instructed not to consider sentencing when weighing a verdict.

Of the 14 years that Jacob has spent in prison thus far, eight of them were spent in the state supermax, Colorado State Penitentiary, where he spent 23 hours a day in solitary confinement. He was sent there in 1995 after prison officials found contraband in his cell: a rope he claims he was using as a clothesline and a sharpened piece of rebar he says he kept to defend himself from other prisoners.

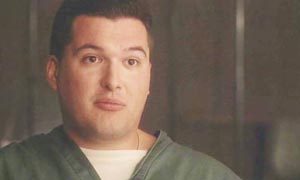

Jacob Ind during his 2007 interview with FRONTLINE.

For his part, Jacob's view of his crime and punishment has evolved during his time in prison. "I don't second-guess what I did, not one bit," he told the Denver Post in 2000. "I'm happier now than I could imagine anyone ever being."

At that time, he even said that he enjoyed his supermax detention, during which he had earned a bachelor's degree in biblical studies.

But the reality of his crime and his sentence seemed to have set in by the time FRONTLINE interviewed Jacob in 2007. "When I was younger, when I knew how much it would hurt to face my responsibility, I'd try to blame it on my parents by saying, well, if they didn't do this to me, ... I wouldn't have had to kill them," he said. "I can't blame my parents for my family's pain, for me being here. I can only blame myself and the fact that I wasn't strong enough to stand up against them."

But Mary Ellen Johnson, who has continued to work on Jacob's behalf, hears in his acceptance of responsibility echoes of the abuse he suffered. "I think for Jacob to say that he's weak and ... that what happened to him wasn't so bad, I think he hears his parents' voice inside of him," she told FRONTLINE. "And to me the system is exactly like his parents. So he just traded one horror for another, because in the prison system they have all sorts of rules and regulations that make no sense. ... And that's exactly what his parents did."

Jacob also sees his time in the supermax differently in retrospect. "At the time, you get used to it, and it doesn't seem that bad. Now, when I think back at it, it seems like total hell," he told FRONTLINE. "Because thinking back on it, it's like almost thinking back on my childhood. It's like pure terror. It's like, oh, no, I don't even want to go back there. But at the time, it's what I needed to heal myself."

RELATED LINK

- "The Killer and Mrs. Johnson"

Alan Prendergast profiles Mary Ellen Johnson, the writer who has become an advocate for Jacob Ind's case, in the March 19, 1998 issue of Westword magazine.

home . introduction . watch online . five stories . state-by-state map . interviews . timeline . join the discussion

conversation with ofra bikel . readings & links . teacher's guide . site map . dvd & transcript . press reaction

credits . privacy policy . journalistic guidelines . FRONTLINE series home . wgbh . pbs

posted may. 8, 2007

FRONTLINE is a registered trademark of wgbh educational foundation.

background photograph © scot frei/corbis

web site copyright WGBH educational foundation