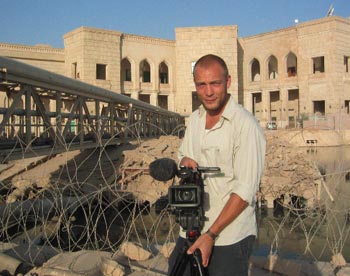

A short Q&A with producer/cameraman Tim Grucza about his embed with U.S. troops in Afghanistan's embattled Korengal Valley.

Grucza is an Australian freelance video journalist based in Paris, France. The first conflict he covered was Kosovo in 1999. Since then his work has been primarily in Iraq, and he is the director of the Iraq war film, White Platoon, which won the Best Feature Length Documentary award at the 2006 Banff World Television Festival. He has worked on several previous FRONTLINE films, including Rules of Engagement, Gangs of Iraq, The Torture Question and Private Warriors.

What were your impressions of Afghanistan and the Korengal Valley? What is it like there?

Afghanistan is an incredibly beautiful country. Soldiers would often tell me that the Korengal would be a great tourist destination for Americans if the Taliban weren't shooting at them.

A logging region, the mountains are a mix of small shrubs, exposed rocks and tall pines, with bald patches on the hillsides either from illegal logging [banned by the government to prevent funding for the Taliban] or from fires started by searing hot ammunition fired from U.S aircraft at insurgents sheltering in the woods.

I spent most of my time based on a small outpost high in the mountains overlooking the valley. The mountains rolled on forever with small villages attached to the side of the hills with stepped green cornfields leading down to the river -- a little like the rice terraces of Vietnam.

The outpost was a dreaded one-hour climb from the main base in the valley. [See a map showing Korengal Valley.] It was re-supplied by helicopter, which dropped a load of "bullets and beans" once a week. They washed their uniforms in old ammo cans with bottled water. There's no Internet or telephone and most of the guys passed the time playing cards and eating MREs [Meals Ready to Eat, army rations]. That was the best part of their day. But a lot of the soldiers preferred it up there, away from the officers and regulations.

Your embed with Bravo Company -- how long were you with them and what was it like?

I was only with Bravo Company for 10 days. It was a busy time for them. They were attacked on a daily basis.

Oddly, most of the guys in Bravo Company were on their first tour of duty; after seven years at war it was hard to believe that there was anybody in the military who hadn't been to either Iraq or Afghanistan.

On my last trip to Iraq in '07 I embedded with a platoon of Marines, led by 24-year-old NCOs [non-commissioned officers] on their fourth tour. But that in itself helped explain it: So many soldiers had done their time. Even in 2004 many soldiers I spoke to wanted to get out. The reality of war wasn't what it was cracked up to be. The army deployed its units for 12- to 15-month tours at a time. The prospect of multiple deployments was daunting to say the least. "Too long, too hot, too dangerous," was the mantra.

In Afghanistan, it was perhaps a mixture of naïveté and youth that kept the guys of Bravo Company in relatively good spirits. No one ever complained. Of course, it was bad to lose Sgt. Sowers in the incident in the film. He was shot in the foot. He was on point, as usual, out in front leading the platoon through enemy territory. One of their best soldiers. He made everyone feel comfortable because he was always calm and professional. When we got back to the camp his guys would tell how he continued to give orders while bullets whizzed overhead and his boot filled with blood.

That's the way they deal with it. Telling stories. It's cathartic. Thankfully, you've lived to talk about it. It helps kill time until the adrenaline passes through your system and exhaustion sends you to your cot and let the dreams sort out the rest. You don't really think about it again after that. I guess that's the way the soldiers get out and do it all over again each and every day.

My producers sent me this transcript of a conversation I had with Sgt. Shriner when I interviewed him after the firefight. Myself and platoon leader Sgt. Young got caught in the second wave of the ambush as we ran across the clearing to check on the wounded. When I hit the dirt I found myself with a rock under my belly, pushing my backside up into the air.

Sgt. Shriner: I heard you started burrowing, trying to dig.

Me: Exactly, I was digging myself a hole.

Sgt. Shriner: One of the best things to do is just find a rock or a tree.

Me: I was too afraid to stand up, cause I was right still in the gap between the building and the slope. Fuck. Well, I thought at least if I got shot in the ass, better than in the head.

Sgt. Shriner: That's what I was thinking when I was running up the hill after Sgt. Sowers. It's pretty ridiculous.

What happened with the incident with the Humvee?

On the ground the situation can often feel "pretty ridiculous." The steep mountainous terrain is unforgiving on both the legs and the vehicles that have to tackle paths meant for nothing more than a donkey cart -- not 5,000-pound up-armored Humvees.

We knew we were going to get hit at one stage or another as we drove down to the bogged Humvee. It was resting precariously on the edge of a ravine, the stream below waiting to break its inevitable fall. The left tire had hit a soft patch on the edge of the road and gravity did the rest.

It was a bad spot on a bend in the road at the bottom of the valley, resembling a natural amphitheater with cornfields, trees and shanty huts where the seats would have been. The insurgents had the high ground all around us, plenty of cover and 360 degrees of possible attack positions. In the past 24 hours there had already been two ambushes, and with daylight there would be more. But leaving the vehicle to the enemy was not an option, so it would be guarded until it could be removed.

Winding our way down into the valley, past the cemetery, the vehicle I was in was ordered to provide cover support while the mechanics removed all sensitive items from the vehicle.

"Oh shit", the gunner above me moaned, "a bird just crapped on me." Everybody laughed. Comic relief to ease the tension.

"That's a good thing," I told him. "In France they say that is good luck."

"Well looks like you got a bit of luck yourself." The well-aiming bird had dropped its load though the turret and all over my camera bag.

The laughter seemed to be going on nervously for too long. Waiting, knowing that you're going to get hit, you feel every second tick by. The previous day I'd sat in a similar position in another Humvee. For two-and-a-half hours nobody said a word. The soldiers sat rigid, eyes darting as they scanned the surrounding cornfields for movement. Looking for the needle in the haystack. Waiting for the inevitable.

When the bullets started cracking and skipping off the roof of our vehicle, as expected, the supposed lucky bird crap was the last thing on my mind. Nobody was hurt in our vehicle, not even the gunner exposed up top. But two Afghani workers were shot, one in the hand, the other in the leg.

The position was ambushed one more time that afternoon before the decision was made to destroy the vehicle with incendiary grenades. Burning at 4,000 degrees Fahrenheit, they melt through an engine block. [Editor's Note: The Humvee incident can be watched in Chapter Six of the online video.]