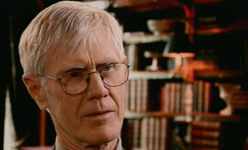

Orville Schell is the Dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California, Berkeley and the author of numerous articles and books on Chinese affairs. At the time of the 1989 demonstrations, Schell was in Beijing and describes here what he saw and the symbolism and mystery of the young man who stood up before the tanks. He also discusses the regime's censorship efforts, how China is a "petri dish" for whether the Internet can be curtailed, and the consequences for the Chinese in making the economy everything at the price of other freedoms. This is an edited transcript of an interview conducted on Dec. 13, 2005.

The students provided the original inspiration in the spring 1989 protest, but it soon developed into a national movement. Can you give us a sense of the scale of that protest by ordinary people?

The whole of that spring of 1989 was something like dropping a pebble in the water and you see the concentric circles of repercussion radiating outwards. It began undeniably with students. But I remember very distinctly the day in [Tiananmen] Square when it became very obvious there were a lot of other people, people in sort of ragged clothes and unshaven. We began to get a sense that ordinary people, the citizenry, had entered into this equation, and they began to sort of boil around the square in a way, which is quite chaotic, and you could feel something uncontrollable building.

Of course from there it moved outward across the country to one provincial city after another -- first to Shanghai, and then it was a whole series of echoes that reverberated out across China.

Can you describe those moments in the square, describe what you saw.

As the demonstrations gathered force and as more and more people were sort of drawn almost magnetically to the square, it became this almost black hole. The gravity was just pulling people into it. I went one afternoon, and there was a little kiosk where traffic policemen normally stand in front of the portrait of Mao in Tiananmen. I walked up there, and you could see miles down either side of the Avenue of Eternal Peace [Chang'an Boulevard]. It was an amazing sight to see these hundreds of thousands of people flowing into the square like the tributaries of two rivers, all marching under these banners. There were people in heavy earth-moving equipment. I remember there were the honey bucket collectors and there were the pilots; there were the hotel workers. It was like this great cross section of Chinese society.

![...anyone standing there [Tiananmen Square] during those weeks couldn't have imagined in their wildest imagination that come 2006 China would be where it is today and the Party would still be enthroned.](../art/schellpq.gif)

Everybody was, for the first time in my memory, out of the closet with their banners held high, declaring who they were and entering the square. What it suggested was that people thought that the old regime was somehow about to fall. Indeed it was hard to imagine how it could be otherwise at that moment.

You've also described an extraordinary transformation that came over Beijingers in those months. Tell me about that change in people.

Well, prior to the demonstrations that broke out in the spring of 1989, there was a kind of very dyspeptic feeling in Beijing. There was inflation, a lot of corruption; there was a feeling that something was brewing. There was also a lot of nastiness about. What happened when these demonstrations began and when this small city began to arise in Tiananmen Square, with blocks marked off and different departments for different universities and hospitals and finance departments, is a feeling of an amazing kind of beneficence that came over people. Throughout the city, crime essentially ceased. …

For 15 days following the declaration of martial law, the army was kept at bay. It never reached the square until the night of June 3 and 4. You were there in the early days of it. How did the citizens, largely the citizens, keep the army at bay?

When the army first came in, the citizens simply swarmed, but they swarmed somewhat fearfully, and they were very, almost innocent, as if the righteousness of their cause would be sufficient to stop this military force. And indeed it was. So you got these very curious situations where in some cases citizens would harangue the military, but very quickly they would be sympathizing with them, feeding them, sort of begging them to come over to the virtuous side from the dark side. …

When the crackdown came, it was incredibly severe. … They came in and used semiautomatic weapons in confined streets. Why was the crackdown so severe?

I think that what happened was by the time the troops came into the city the second time, there was a level of humiliation that the leaders had experienced and a level of fearfulness that the whole proposition of the Chinese Communist Party's ability to rule unilaterally was slipping from their hands. This put [the government] on rather a hair trigger.

But one should never underestimate the role of the feeling of loss of face, of humiliation, in Chinese dynamics. I think the leaders had felt that they had been thwarted in the most obvious and humiliating manner, and the second time around, they brought in troops from far away who didn't have connections to Beijing, whose kids weren't in the square, and they decided they would brook no obstacle.

Can you remember how you responded when you first saw that picture of the young man stopping the column of tanks, what it said to you?

In many ways, the demonstrations in the spring of '89 [were] about the power of the individual against the state, and so it seemed to sum up in the most graphic and symbolic way, I think, what everybody had been feeling: the power of the citizen to actually have an effect on the might of the state.

What does it say about China, though, that we actually don't know who he was and a mystery still surrounds his fate?

The truth is there is much that the West doesn't know about China. Again and again and again, we look at China, and we don't know what we're seeing. We look at the president and present Party chief, Hu Jintao. We really don't know who he is; we don't know what he stands for. It is not clear at all, very opaque. So in a certain sense, it isn't surprising that a detail like this could go uninvestigated and that no conclusive end to that story can be told.

Have you ever speculated on what probably happened to him, or is that really a waste of time?

I think two things are possible. One, in the tumult of that moment, he just slipped back into the crowd and disappeared. On the other hand, I think if he was identified, he probably would have met some fairly, fairly stern retaliation and punishment.

Including the possibility of execution.

Anything is possible in a situation like that. It doesn't take much … to earn a lot of umbrage very quickly and find yourself in a very difficult situation, in prison or otherwise.

I told you about the experiment we conducted in the university [Beijing University, also called Peking University]: passing the picture around of that young man who stopped the tanks and how there was absolute incomprehension among the students. Now, OK, those kids were 3, 4, 5 when it happened, but the idea that the university was right at the center of all this and that there is no discussion, there is no oral history, and there are not parents that are talking to them about it -- how has the Chinese government managed so successfully to keep out information and knowledge that it doesn't want to come in?

Well, one way the Chinese government has managed to control the dialogue and the discussion of the past is by controlling the media and publishing, and that it's done quite effectively. It's no accident that this is an area that they are least willing to compromise in as these other rather amazing reforms go forward in the country. I think they recognize that if they lose control of the dialogue about the past, they in effect lose control of the present and the future. That's only to say that maybe after all, even they recognize the past does have consequences and must be dealt with incredibly carefully lest it get away.

I think that the toll it takes on people is considerable to contain all of those feelings. I mean, everybody who had anything to do with that 1989 movement had on the one hand these very deep feelings for the first time of being almost completely free: The media was free for a period of a week or 10 days; it was reporting like a normal media; people could and did say whatever they thought. It was an amazing unleashing of all of these senses of what was forbidden and couldn't be spoken. And then of course all that ended. Now, the young people didn't have that experience, and they can't even experience it in virtual secondhand form because the media doesn't facilitate that.

But I don't think one has to be too indelibly Western to believe that the past does live on, and indeed nobody had a greater and deeper appreciation of the relevance of history than China itself. In traditional times, dynastic histories were written. They were always studied; lessons were learned. When things went awry, China had a way of turning back to look at … several millennia to see what was the proper way to rule, what was rectitude for a leader, what were the values that needed to be restored to society. To be so ahistorical now … is in a certain sense a violation of a whole tradition in Chinese culture of using the past to correct the future, to keep straight with the past.

An argument that is sometimes used is that if there was greater freedom, China would kind of fall apart. Is that the reason? Or, as most of the dissidents say, are we really talking about a group of privileged people who are anxious to hold on to their privilege? What is keeping China this way at this point?

I think there is no doubt that the present leadership fears relaxing control, particularly over the media and discussions of events like 1989 and a myriad of others, because it fears that once the discussions begin -- like those demonstrations in 1989 -- they will be very hard to stop. In this they may be right.

But there is another theory that says if you allowed a modicum of discussion to go in an orderly fashion, it would serve as a pressure-release valve, whereas if you don't have any discussion, at some point the pressure will build up. What the Party has relied on to prevent the pressure from building up is to allow people to exercise all of their ambitions and urges to be able to advance themselves and to have lives on the economic side of the ledger. This was Deng Xiaoping's great moment of genius. After the massacre of 1989, he in effect said we will not stop economic reform; we will in effect halt political reform.

What he basically said to people was: "Folks, you are in a room. There are two doors. One door says 'Politics'; one door says 'Economics.' You open the economic door, you are on your own. You can go the full distance to basically whatever you want: get wealthy, help your family have a bright future, move forward into a glorious future. If you open the political door, you are going to run right into one obstruction after another, and you are going to run into the state." People logically being practical -- and Chinese are very practical -- opened the economic door. They wouldn't open the political door. It was foolish to do so.

But is it a mistake to talk about this as countrywide? Just in my limited travel to the countryside, I really felt that there was another China which was being given very limited economic opportunities, if at all. And indeed, for them, certain things were being taken away, such as free education, free medical. It seems to me that that economic solution was only provided to a minority as a whole -- maybe just 200 million.

Well, China's paradox now is that a larger quotient of people than at any time in the last 50 years are economically better off, but there is a huge number that has really stagnated, and the gap has opened up between the wealthy and the poor. In many ways these gaps are hauntingly reminiscent of what happened in the '30s under the Nationalists, the Kuomintang, when coastal China got rich and peasant China remained poor. And if you remember, what was the Chinese Communist revolution all about? It was about angry peasants. Now we seem to be circling back in a very haunting way, with all of these peasant uprisings and instances of insurrection and protest -- whether it is over environmental pollution, confiscation of land, corruption. … This is only to say that maybe what goes around comes around.

But … creating a disparity and a point of tension will not be too dangerous unless the economy as a whole begins to wobble. We know economies are always cyclical, so sooner or later, China has to be ready for that. Then, of course, when economies wobble, you have to start depending on other things -- the political system, legitimacy of the government, common shared values that keep people together, a sense of common purpose. Right now, all the Party has to go on is, one, economic growth, and, two, they can excite nationalism as a unifying force.

I was shocked at the sort of naked commercialism when I talked with young people and their obsession with style and the rest of it. Has the turning point that was 1989 left an emptiness, a cynicism, which is now, certainly among the young, just filled with commercial fluff?

I do think commercial culture, which is on a tear now in China, has very much served as a surrogate for many other aspects of life throughout history and in other societies that have also nourished people. I mean the times in history where religion was important or art was important, where culture, politics, warfare.

But this is a kind of a monocultural diet of consumerism now, and it has indeed rushed into this vacuum that was left in the wake of 1989, which I think in a certain way it would be fair to describe as the end of idealism in China, and the end of that hopeful sense of a somewhat more diversified life, where you could actually be an archaeologist; you could study literature; you could be in politics, and you can imagine being sustained by that. But '89 ended that, sadly. …

So [making money], that's what's available. Naturally people will take that rather than nothing, and they'll be glad for it. I think in many ways Chinese are much happier, at least the ones who have gotten wealthy. It is an amazing miracle what has happened since 1989, and anyone such as myself standing there during those weeks couldn't have imagined in their wildest imagination that come 2006, China would be where it is today, and the Party would still be enthroned.

What do you say to people who say, look, 1989 -- why dig into the past? China has moved on; that's no longer a topic anymore. Is there any strength in that argument?

One does have to hand some credit to the Chinese government for picking up after this disaster. At the same time, of course, they are trying to maintain their own power and also promoting a huge amount of development and well-being in China, at least in terms of the basic necessities of life for an awful lot of people.

But it's a hell of a high-wire act, and the price for having done that -- you know, a lot of economics [is] basically ignoring other aspects of life which I fundamentally believe human beings ultimately need. They need some spiritual meaning to life. They need some sense of values, idealism, hope, that transcends just getting wealthy. China now entered a period where, without quite knowing it, it has viewed the market as a kind of freedom, and indeed it is. But it also is a master; it has its imperatives. There are certain things the market likes and it doesn't like.

China has entered this paradoxical world as the sort of antidote to remembering 1989, in which the economy is everything but where they required a new master. They had the old master of the Party and the whole censorious apparatus that that entailed, and now the market is both a form of liberation and a new form of insulation. I don't think this discussion has really been had in an adequate way in China. There are some people belonging to what they call the New Left who are looking at this sort of extreme form of marketization as dangerous. But as long as you don't have the media in your hand, then you can't vector these discussions out. These people are of relatively little consequence.

What about the question of whether a free-market capitalism will lead to personal freedom?

Well, that is the question, isn't it, whether an open market can electively lead to a more open society. I would say it doesn't preclude it, but it doesn't ipso facto lead there. It could just as well lead to the re-enthronement of the middle class, who finds it within their interest to keep an authoritarian system in power to protect their interest. We've had many examples of that in the world. We do have some interesting wild cards, like the Internet, and I think the Internet is fundamentally a liberalizing force.

But I think China, in this regard, is the great petri dish for whether the Internet can be brought to heel or whether it is on the face of it a sort of spontaneous free agent that will catalyze China into a more open direction. And the returns are not in yet. China needs the Internet, and it's using it to good effect in business. The Party is using it very effectively to help communicate with the provinces, the counties, the police units, the army. It isn't purely an engine of dissident energy or of individualism or of democracy. We've seen many technologies from telegraph to radio to television that have been brought to heel quite nicely by commercial interests. So we'll see.

Now, you can't control the Internet completely. I don't even think that's their aspiration in China. But their aspiration is to make it difficult enough for most people so that they'll stay within the confines of the intranet, not the Internet, the intranet being China's hermitically sealed room which is connected to the outside world by a very limited number of gateways. It is through those gateways that all the information to the outside world flows both ways, and that's where it can be controlled.

What do you feel about Western companies and corporations that are assisting China in censorship and even in refined techniques of surveillance?

I think there's no doubt that Western companies are helping the Public Security Bureau, the People's Liberation Army, the Communist Party to maintain themselves in power, and this is what companies do. They sell to whomever wants to buy, so in a certain sense, you can't fault them alone. This is traditionally the role of government, to lead companies, to lead society, lead multilateral organizations. I think there's a failure of leadership at every quarter, and the market is so seductive right now, nobody wants to risk being shut out, so everybody just throws cares to the wind; they make their excuses and they go in, because they figure they'll be out of the running if they don't.

But we are living in a world which is more commercial than at any time in human history. This is the value; this is our currency. We judge ourselves by how well we do in the market and less and less by other things. Maybe this will change, but I think it's important to remember that this is the case.

It seems there are no checks and balances, whether it's a decision on where to build an Olympic stadium, where you don't have to go through the fuss of speaking to local citizens, getting their consent, dealing with protests, or whether it's simply allocating the wage that you would pay at a factory, or whether you'll pay at all, because there's no union protection. This is absolutely unbridled.

There are a few checks and balances in China today. Yet in many ways, this makes it a very competitive and, in many ways, a very seductive model. They can get stuff done. We thrash around in the West trying to build a bridge, a freeway, and [we confront] environmental impact reports and citizens groups raising hell. China can be efficient. But is this a long-term solution? Ultimately does society not need some way to express itself without the whole boiler becoming so pressurized with discontent?

Today I'd have to say they've done a pretty good job. But of late, there have been some agents that have been catalyzing the situation in China that are quite alarming -- I mean, some 74,000 instances of unrest reported last year in China, up substantially from the year before. This is troubling. And I think it's very troubling to the leadership. What it says is that people are not finding adequate ways to seek redress of grievances, and that finally, that verity is one that you can't simply turn off by having a lot of Gucci luggage available for people.

… I do think that there are many hopeful things that are happening within China. The question that really needs to be asked is, is China a balanced society, and does it have a prospect of becoming a balanced society? Now some would say, you have to do one thing first, and then you do another. Deng Xiaoping said it's OK for some people to get rich first, implying the others would follow. Well, I'm not sure what the best way is to raise the sick man of Asia up, which China was deemed to be early on. As I say, we're looking to see whether this model of development works. And there are a lot of people very interested in it, like [President Vladimir] Putin in Russia. Nice, authoritarian capitalism, a sort of Leninist market system, could be quite appealing. No fuss, no muss. Just keep trains running on time, keep the growth rates high, and keep the shopping malls full.

A view expressed to me for about five years by people, business people, is very simple. It says that a free market economy is an information economy, you need free flow of information, you have to know what the jobs are, you have to know what the commodity prices are and ergo personal freedoms will follow. You can't keep this information out, it is going to change things, give us the free market and it is going to change things.

… I think open markets can help lead to open societies but it takes a little more than just buying and selling and ultimately you arrive in paradise. And I think that's the element that is missing in China and I think actually what is wanted is the sense that one wants to get to an open society. China talks sort of vaguely about democracy but sort of socialist democracy with Chinese characteristics whatever that means. I frankly don't think they really want to get there that much, maybe, way, way, way down the line. … In other words there isn't a conscious sort of aggressive effort to plan what do we look like.

Truth is, China hasn't any idea where it's going. Now it's getting there really rapidly and in a very impressive way but what is the ultimate goal? What does it aspire to be? Not clear. And I don't know if that matters. We Americans were raised by the Founding Fathers with a very clear plan, but you know when the last dynasty fell and Sun Yat-sen came along he had a very clear plan too for how to create a republic. There is no such thing now and indeed there is not even much of a discussion, certainly not in public, a little in private. Now is it possible for China to reform itself with no idea about where it is going except it wants to do more faster? This is a question for which I don't have an answer.

You mentioned earlier the 74,000 uprising number that was claimed by officials. Does that not suggest that 16 years after Tiananmen, the society is in a very tense and unstable state?

I don't think there's any country in the world that is in a more unresolved state than China. This, despite the fact that I also am in awe of the amazing progress they've made and wealth generation that has happened -- the industrialization, the economic miracle. You have to acknowledge that. But you also have to remember that China is in transition, from a system laid down in the '50s when Joseph Stalin led Russia, to something else. We don't know what it is. But there are a large number of institutions, of policies, that haven't been resolved. It's unclear. There's a huge amount of tension. It's like a land of a thousand earthquake faults. And one of these faults is between the rich and the poor, between peasants and the Party, between corrupt officials and the people.