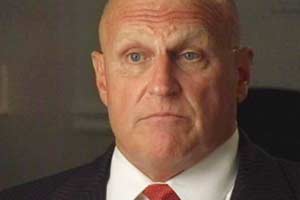

In this interview, Armitage, who served as deputy secretary of state in George W. Bush's first administration, outlines why he believes the current situation in Afghanistan is "a little more dire than we've seen it publicly portrayed" and why he thinks the stability of three nations -- Afghanistan, Pakistan and India -- is at stake. He also recounts his now-infamous Sept. 12, 2001, conversation with Pakistani intelligence chief Gen. Mahmood Ahmed in which he outlined a series of "arduous and onerous" demands on Pakistan. He recalls saying: "No American will want to have anything to do with Pakistan in our moment of peril if you're not with us. It's black or white." This is the edited transcript of an interview conducted on July 20, 2006. Editor's Note: This interview was conducted before Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf said Armitage had once threatened to bomb Pakistan into the "Stone Age," a charge which Armitage denies.

The current situation on the ground in Afghanistan -- what are we facing?

I think we're facing a resurgent Taliban, one that feels blusty and bold enough to travel sometimes in company or larger-sized units. We've seen recent problems of towns being taken by the Taliban or retaken by government or coalition forces. So we've got a resurgent Taliban probably aided by money from drugs which are grown in Afghanistan.

But this is not just a successful spring and summer offensive. This, as you see it, is a longer-term trend or a Taliban that's gotten a new hold on --

I think they have gotten a semi-hold on things. We haven't moved, in my view, fast enough to consolidate a rather stunning victory. We didn't push enough to get all the instruments of government standing up in a relatively uniform way.

So it's a fault of our inability to stand up a government and institutions in Afghanistan?

Well, to some extent I think it's our fault. It's not totally our fault. Afghans have to be responsible for their future. But I think that the fact that we so rapidly turned our attention to Iraq turned us away from Afghanistan, in my view, a little prematurely.

There was a vigorous debate about Iraq. Was that put in terms of "Let's solve the problems in Afghanistan"?

To some extent. Let me be clear: I was not opposed to the war in Iraq. The proposition of removing Saddam Hussein was an eminently sensible one. I did have some real questions about the timing, because I thought a later timing would allow us to more consolidate Afghanistan and to perhaps put together a more striking coalition.

But what was the thinking about the state of Afghanistan at the moment that you went into Iraq?

Well, I think it was more a question about the state of Iraq when we went into Iraq. We have one nationally elected leader. He was not willing to wait for reasons of his own. He was not going to, as he says, sit back while the smoking gun became a mushroom cloud and things of that nature.

I do think that we were a little more optimistic about Afghanistan early on. We had great respect for [Afghan President] Hamid Karzai and his valor. He was such a good figure on the international stage that we assumed things about the rapidity of reconstruction that were not so reasonable in hindsight.

We also stretched our resources thin, did we not?

Well, in terms of money, obviously we're not printing new money every day, and the $18 billion that went to Iraq right after the invasion or shortly after could have been well used in Afghanistan as well.

Now, when you talk about the current situation in Afghanistan, you also have to talk about Pakistan.

You sure do.

Why?

Well, I think that first of all, there's a not-good relationship between the two countries. I think [Pakistani] President [Pervez] Musharraf and his colleagues can be rightly frustrated. They've been fighting mightily in the tribal areas, or the so-called FATA, Federally Administered Tribal Areas. They've lost 600, 700 of their very fine soldiers, and they get no credit for them from their point of view. Instead, they are subjected to cries of indignation from Kabul and beyond that they're not doing enough to stop cross-border operations. So to some extent I think our friends in Pakistan feel that they're being made a scapegoat for the inability of the coalition and Afghan forces to complete the mission.

Well, what about that? Are they being made scapegoats, or are they not doing enough?

Well, I think if you lose 600 or 700 soldiers, it's very hard to say you're not doing enough. That's quite a sacrifice for a country like Pakistan. Could they do more? Sure. I think we could all do more. We could put more troops ... into Afghanistan ourselves. So we could all do more. I think the question is how much more can they do in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas. These are rough, wild lands, and they haven't belonged to anybody for an awfully long time.

So you don't buy it when Karzai complains or when his chief of intelligence complains that this is really a double game on the part of Pakistan; that their heart's not really in it. They're friends of the Taliban.

Well, look, they had a 10-year policy of supporting the Taliban and the Pashtuns, and I think it's hard for any nation to turn away from 10 years of one policy immediately to go to the reverse. I am of the opinion that President Musharraf himself is absolutely sincere in his desire to root out Taliban, because, see, he realizes to some extent the fortunes of the 160 million people in Pakistan are tied to the fate of the 25 million people in Afghanistan.

You believe that he is sincere. You told congressional leaders back in October of 2003, "I personally believe that Musharraf is genuine when he assists us in the tribal areas, but I don't think that that affection for working with us extends up and down the rank and file of the Pakistani security community."

I said that concerning ISI [Inter-Services Intelligence], which is the intelligence community, and I still think it to be true.

What is true exactly?

I think that there are sympathies in some segments of the ISI for the Taliban and for the failed policy of 10 years.

But Musharraf is the man in charge. Why can't he clean up his own military and his own ISI?

I think to a large extent he has cleaned up the military. But let's remember that President Musharraf was a fellow who was bombed twice, nearly cost him his life. Some of the miscreants who committed those acts were from his own military. So he's in a precarious position himself. I don't think -- though he is in charge, and the buck does stop there -- that he could actually know the sympathies and the sentiments of every soldier and young officer in the ISI. I just don't think it's possible.

Well, there's a question out there as to whether or not we're dealing with a false ally who's playing a double game or we're dealing with a weak ally in Musharraf. And you would say he's weak?

Yeah, I have been from the beginning a big fan of President Musharraf, notwithstanding the extralegal way in which he assumed power. I think he's genuine in trying to improve the lives of the people of Pakistan. I've noted in the past under democratic governments and under martial law the people of Pakistan have been royally and liberally screwed. Regarding President Musharraf, there's never been a taint of corruption to him. It says much to his credit.

I think he will fail in his "enlightened moderation" program, however, unless we continue to support him and unless we and the coalition and most importantly of all the Afghan people win their battle in Afghanistan.

But can they win in Afghanistan if the ISI and elements within the Pakistani military who are friendly to the Taliban continue to allow sanctuaries to exist in Pakistan?

Well, let me separate myself from some of your comments. I talked about ISI; I did not talk about the Pakistan army. I think they are, as I say, sacrificing a lot of their young men in the Federal[ly] Administered Tribal Areas. So I want to separate the two.

Yes, I think that ultimately we can be successful and Afghanistan can be successful, but it really is going to take a lot of effort on the part of Afghans themselves. It's not as if every ISI member is out funneling weapons and money, etc., across the border. I don't think we can blame the entire problem of Afghanistan on Pakistan. I don't think it's fair.

So you reject the idea that we have to address the situation of sanctuaries and command centers based in Quetta or in Miram Shah before we can advance the cause in Afghanistan?

I don't reject the idea, ... but it's not pivotal in my view. The problem of Afghanistan is in Afghanistan and has to be resolved there. ...

Can you describe the nature of the relationship between the ISI and the Talibs?

No. I know previously the ISI was the main focus of support for the Talibs during about 1992 to the end of 2001, but beyond that I haven't got any intricate knowledge of how they are right now.

I meant historically. I mean, in fact, they built them up.

Yes.

That's a fair characterization that they built them up and maintained them.

Yeah. Yes, they did. They built them up, and it's a very complicated and complex equation. It had to do with the Northern Alliance and the Tajiks, who were the main people in the Northern Alliance who were supported by India and laterally by ourselves. So this was a much larger game in terms of the ISI back in the day than simply Afghanistan.

But the ISI, it's fair to say, built up and maintained the Taliban as a key ally in this greater regional game.

I don't think there's any question.

And so on 9/11, suddenly you've got these guys who are being asked to completely reverse their allegiance and to betray those very people that they were quite close to. It's a tall order, isn't it?

Well, yeah, I think it was a tall order. But I would have phrased the question a little differently. I said what we asked of the Pakistanis right immediately after 9/11 was that they stand up and do the best thing for their nation. ...

When President Musharraf made his decision to join us and be with us or against us, he saw, I think, several things simultaneously. He saw that, in his view, the relationship with Afghanistan and the policy towards Afghanistan was failing, number one. Number two, he saw an opportunity to relatively correct the relationship with the United States, which has been adrift for more than a decade, much to the detriment of both the military and society in general. And third, I think he saw an opportunity to have Pakistan, which is one of the larger nations in the world, occupy a grander place on the certainly regional, if not world, stage. I think he saw these things all at the same time.

When I asked him in an interview just a few weeks back what was in it for him, he didn't say any of this. He said: "What's in it for me is that we get a lot of money from the United States. We're going to get F-16s, and it's helped our economy."

These are all true. But he did say part of what I said: that he saw the opportunity to better the relationship with the United States and be on the world stage, or at least regional stage, in a better way. The only thing he didn't say was that it was apparently a failed policy in Afghanistan.

The support for the Taliban.

Yeah. ...

On Sept. 11, you made a phone call over to [ISI Director] Gen. Mahmood [Ahmed], who was here in Washington visiting.

He was a guest of [former CIA Director] George Tenet.

And tell me what happened next.

I asked him to come into my office and told him, basically, that he was here at historic and a momentous time and that Pakistan had an opportunity to change and make a decision to come with the United States, and that I was going to make a series of demands on him that would be very difficult to Pakistan. But he had to be under no illusions as to the difficulty or the amount of energy the United States was going to put into this.

I literally then took him privately to my room and said: ... "No American will want to have anything to do with Pakistan in our moment of peril if you're not with us. It's black or white." And he wanted to tell me about history. He says, "You have to understand the history." And I said, "No, the history begins today."

He came back in the next day, and Secretary [of State Colin] Powell and I had put our heads together and came up with a list of demands, which were very arduous and onerous for Pakistan, and asked him to get these immediately to Gen. Musharraf and get a decision. ...

I don't think Gen. Mahmood cared for me very much or liked me very much, but he can't say I gave him any bull. ...

You had made seven demands.

Yes, I did.

And those demands had been cleared with the White House.

No, they had not.

So you and Secretary Powell came up with a list of demands without consulting with anyone else at the top.

That's right. And laterally, after we had presented them -- things were moving pretty fast -- to Gen. Ahmed Mahmood [sic], and we got his answer back, the secretary called Gen. Musharraf, President Musharraf, and got insurance that Mahmood was carrying the mail and it was answering for him. We then, in a video conference, told the interagency community ... what we'd done. The president said, "That's great; that's terrific," and the secretary of defense laterally asked if he could have a copy. ...

And among those demands, you asked them to stop all logistical support for Al Qaeda.

For the Taliban. ...

For both.

Yeah.

So were they giving logistical support to Al Qaeda?

No. Our view was the logistical support for Al Qaeda could be in just letting them transit. The logistical support that they were giving the [Taliban] could find its way into Osama bin Laden and his colleagues' hands. That was the logistical support we were referring to.

And he gave you no argument on any of those?

No, I just read them off, and I gave him a piece of paper that had them. The only thing we didn't ask him to do [was] cut relations with the Taliban at that time.

Because?

Because we had citizens that were held by the [Taliban]; we had two young ladies. And we felt as long as there was a possibility of getting [them released] -- and thank God, they were safely gotten out -- we wanted them. In fact, the Pakistanis literally came to us and said, "Can we break relations with them now?," and I said: "Not yet. Please hold on."

You told him that the demands were nonnegotiable?

Uh-huh.

And Musharraf's response to Secretary Powell?

He said just that he's in; he understood the demands, and he was in.

[Did he] express any other sentiments, any worries, any concerns that he had at the time?

None to us that I recall. And Secretary Powell didn't tell me of any.

How do you think the deal has held up?

I think they did what they said. ... I'm pretty happy with the way Pakistan handled themselves, particularly in the first year or so after.

Why didn't you ask them [for] or demand from them access to the tribal areas?

You've been to the tribal areas. You know what that would have done to us? We'd have gotten bogged down in there just as the Pakistani army is bogged down in there. We felt that was their business.

We were introducing or putting our nose under the tent of a rather volatile population. I'm not talking just the tribal areas; I'm talking Pakistan. We knew this. Secretary Powell and I both had had a lot of experience in Pakistan over the years, and that was seen, at least by me -- I'll let Secretary Powell speak for himself -- as a bridge too far.

However, the Pakistanis have struggled to get control of many of those regions, those tribal agencies.

Pakistanis struggle just as the British during colonial times struggled.

You don't think we could do better?

Unsuccessfully. No, I think Pakistan has a somewhat better understanding of the tribal areas. And to the extent no strangers are welcome, they're marginally better than a U.S. stranger would be in the tribal areas, particularly one who's tramping about with weapons. This is a historically volatile area, and I think we'd have been in real trouble if we had gone in large numbers in those areas.

You had people in the Pentagon who wanted to go into those areas. Was there much debate at the time?

There was debate, but it wasn't a rigorous debate, because I think, notwithstanding the fact that there were some people who did, just as you say, want to go in, there were plenty of others who realized this was a bit of a quagmire. Better be careful: We've got fighting on one side in Afghanistan; we don't understand the tribal areas; they're something that we would really be strangers to, and we'd better stay out of it. That held the day.

They've had a relatively successful time of rounding up some of the Al Qaeda leadership.

Well, they killed some of the Al Qaeda leadership.

… They've had less success against the Taliban.

Yes, particularly the big cities. Yeah.

But in the tribal areas, along the border, where sanctuary has been provided by tribesmen to the Taliban, they've had less success there. Why?

I think because Uzbeks and others who have been killed out of the Al Qaeda organization were seen more as strangers, while the Talibs [are] primarily [Pashtuns], who are seen more as cousins and things of that nature, so I think they're better protected by the tribal leaders, tribal peoples.

Is it also because the army also has a view that these are their cousins and, in many cases, literally their brothers?

My view of this is that the Pakistan army actually has behaved better than I had hoped for, when initially, as you remember, a couple years ago, when they first went into the tribal areas, they got smacked pretty good. They lost 70 or 80 right away, and I thought this might be something that causes them to really say, "Wait -- this is not where we want to go."

Well, they did start negotiating at that point.

They did indeed. But they screwed up their courage and went back in, and they've suffered a lot. So I wouldn't attempt to say that that feeling that you described is nonexistent in some elements of the army. But by and large, they followed orders.

And I'm unaware, by the way, of any units not following orders. I've not heard of that, even anecdotally.

Well, it's a pretty closed region.

Fair enough. ...

They were asked by us to seal the border, or at least put a blocking force along the border there.

Right, yeah.

During the battle of Tora Bora, did they perform well in that function?

I can't say. From what I've read about Tora Bora, nobody came out of it looking particularly astute or capable. It is argued, and we know it in hindsight, or we feel it in hindsight, that Osama bin Laden was there and he escaped through one of the bazillion mountain passes into probably tribal areas. Whether they did enough or not I can't say. ...

But you were in a position to be watching and looking out for what they put on the border.

Yeah, but I'm not all-knowing. You know, I had a day job; I was deputy secretary of state. I didn't spend my time pouring over the operational maps. Those are details for operational commandos. We were also involved in other activities at the time. So it wouldn't be fair to say I was staring with a magnifying glass at satellite photographs looking for the placement of troops on the border, because I wasn't.

I guess what I'm tiptoeing up to here is the fact that right around the same time, you had a crisis in eastern Pakistan, in Kashmir.

Yeah.

What impact did that have on their ability to block the border.

It obviously just sucked troops from west to east, first of all, in Pakistan. Put another way, it made deployments of troops on the east and the west less possible, number one, and also raised the tensions with India at a time where we needed Pakistan's attentions focused on Afghanistan. Those were the complicating developments.

And you were running in there at that time.

I was running in and out of there quite often at that time.

What can you tell us about that sort of juggling act between wanting them to get more troops over here and their need to prevent India from invading them?

Well, from our point of view, the stakes were a lot higher than that, because if you remember, both sides deployed huge numbers of troops, particularly after a later event -- that is, the attack on the Indian parliament -- and the specter of nuclear war was very real. Embassies were being drawn down, businesses had closed, and we had a real possibility of nuclear war, not just a conventional incursion or invasion.

So suddenly bin Laden getting free in the tribal areas seemed like a minor concern.

Well, it did, when we would be talking to people on both sides of the line [in] Pakistan and India, and they're talking about not only the possession of but the use of nuclear weapons on each other. We had done the studies of the cloud -- how far it would drift and how many of the population would be injured by that. This was a very real thing. So the stakes were a lot higher at that time than just Osama bin Laden. ...

Was there any thinking at that time that Kashmiri militants were actually doing a favor for their brethren?

No, but there was big thinking at that time -- and I've had these discussions with President Musharraf -- that these militants eventually would turn on him and that they were Al Qaeda associated, at least philosophically if not more than that. … And that eventually this was a tiger that would be very difficult to dismount. That's why we put so much pressure on them to dismantle the camps.

Was the light just coming on in his head that these militants were a threat?

Listen, let's not assume that President Musharraf doesn't have a good grasp of his own realities. You used the term "juggling," and his very much was a juggling or balancing act with his populations, with what he wanted to accomplish, with Kashmir and Kashmiri militants, which is a relatively popular cause in Pakistan, no matter how reprehensible their methods may be.

He's balancing all these things. And he realized the truth of what we were saying, or speaking with him. We weren't lecturing him. We were just talking about the practical difficulties of having these groups on your soil and the fact that they would eventually turn against him as he continued toward enlightened moderation, which is not the way they wanted to go.

Pakistan's strategy of making deals with tribesmen and people like Nek Mohammed -- how did this strike you?

Temporizing. You make a deal today -- deals don't stay generally in the tribal areas; they don't stick. Let me put it in another way: You can rent them; you can't buy them. So I considered it temporizing while we tried to solve another problem. ...

But this is in '04. What are they juggling in '04?

I think they're juggling exactly the same thing, like the society, which has not seen the benefits of the economic changes that President Musharraf and Shaukat Aziz, the prime minister, are trying to bring about. Still some neuralgia, particularly in the west of Pakistan, about what's going on in Afghanistan. The fact that the government of Afghanistan is badgering constantly the government of Pakistan -- all these things are going on. They haven't abated.

We're badgering them, too. [U.S. State Department Coordinator for Counterterrorism] Hank Crumpton went in and said at a press conference in Kabul, "You're not doing enough." And when President Bush went in there, he said, "I came to see if you're still on our side."

He came away feeling they were still on our side. And President Bush is -- what he said when he came back, and Hank Crumpton, who's an excellent guy, I bet he wishes he had that comment back. [I bet] he wishes he'd use the formulation I've used, which is "We all need to do more," which is what I happen to believe. ...

I expected, going into his interview, that [President Musharraf] would be defensive; that he would say, "You know, we're doing well in the tribal areas." He says: "No, we're not doing well. We've got big problems. It's a big problem not only in the tribal areas, but in the settled areas. There's Taliban influences spreading." And when I suggested that there's a lot of people around who think you've lost South Waziristan, he agreed with that. ... He has a more pessimistic view of it than you do.

I haven't expressed myself as optimistic or pessimistic. I have said that if Afghanistan is not successful, Pakistan -- not talking South Waziristan -- Pakistan, the nation, will not be a success. Now, that sounds to me like a pretty strong statement. I believe it. And I think you could probably put President Musharraf and I pretty close together.

I said earlier he was frustrated by the fact that the fate of his nation of 160 [million] is tied to the fate of a much smaller nation. That's a fact. And then the equities just to carry through with India, for all of us, for the United States, for the relationship we've developed, … a radical Pakistan with nuclear weapons would be a rather dramatic rapid change in the equation. So the stakes are enormous.

What is the importance of Pakistan to the Taliban who are fighting inside Afghanistan?

I think to the extent they are able to get some hospitality from the tribal areas, they're able to remove themselves to some extent from the shock temporarily. Beyond that, I am not smart enough or informed enough to know how much actual money and things of that nature trades hands in the tribal areas, but I know there's a lot of money up there historically. It's always been an area of large trading concerns and a lot of money involved, so I suspect --

The tribal areas.

Yeah.

A lot of money.

Yeah. You bet.

People don't think of it that way.

No, because they're closed societies, and people are not walking around in $2,000 suits.

The use of the Predators in the tribal area, how difficult was it to get Pakistan to agree to that?

I'm not going to talk about it. ...

Why is this an area that's so off-limits?

I think it would be obvious without mentioning the Predator pro or con. It's quite obvious that foreign presence in the tribal areas is not a generally welcomed phenomenon, and it does look, to some extent -- wouldn't it? -- that a country is not fully upholding its sovereignty if you have foreign troops running across your territory. ...

Steve Coll feels, in no uncertain terms, that we cannot solve the situation in Afghanistan if we cannot get more cooperation out of Pakistan to go deeper into the ISI. It's not that he believes that Musharraf is playing a double game. In his words, "He's a weak ally." And I'm a little surprised, not that you support Musharraf, but that you don't agree the problem in Afghanistan has such deep roots in Pakistan.

I do not disagree that the problem of Afghanistan has very deep roots in Pakistan at all, but I see the problems of Afghanistan as much more complicated than being able just to blame the problem on Afghan[istan]'s eastern border or Pakistan's western border.

I see a huge and growing drug problem, which fuels all sorts of problems. I see weak infrastructure. I think [there are] a lot of things which allow the Taliban still to swim among the people, and it's not simply a function of Pakistan's western border. So I see the problem of Afghanistan [in] much more dire terms, perhaps, than Mr. Coll, but I don't disagree with the deep roots, the Talibs --

What are the deep roots? How would you define them?

To some extent, tribal affiliation.

Pashtun.

Pashtun affiliation. And to some extent a desire to still play the great game vis-à-vis India, which you haven't mentioned, and, as you know, putting consulates all over Afghanistan, much to the dismay of the Pakistanis. So the roots are deep and complex -- familial, tribal, perceived national interest in some corners from Pakistan, perceived national interest.

What do you mean by that?

Vis-à-vis India and the competition of India.

And you haven't mentioned Baluchistan in this.

I haven't.

That's another thorn in Musharraf's side.

Yes, it is. And the allegations there, of course, are that the Indian government is sponsoring terrorism. But look, Baluchistan -- I don't know if that's quite fair, because Baluchistan is another totally wild area.

The Baluchis are historically extraordinarily independent and extraordinarily tough and wily. But you're right: It's a thorn in his side. But it's a different type of thorn than the one we've been talking about, which is Taliban and Al Qaeda. [Baluchistan] also has, as you know, ... an Iranian angle to it.

Right. But it limits their ability to move successfully in Waziristan or any of the tribal agencies. They've now got trouble from Bajaur all the way down to South Waziristan. ... I mean, one travels in Pakistan and realizes that there's four countries there that are sort of stitched together through Islam, and a modern secular state. ... It's a very barely viable state, it seems, at times.

Yeah. And I've always felt, in Pakistan, there's a race against time. I've seen it in what I would consider relative good times -- and I'm talking in the early '80s, where I thought that they had a real shot at things -- and then when they continued there on their nuclear path, and we had to disengage from them, a 10-year divorce. By the time I had re-entered Pakistan after [an] almost eight-year absence, in fact, I was shocked at the changes in society.

I'm pleased to say that over the -- at least in my observation -- on my last meetings with President Musharraf, I was riding there with our ambassador, Ryan Crocker, and I said, "Ryan, I must tell you, I've been in and out of Pakistan for 25 years, and I'm feeling a lightness, a little more lightness in society," which I thought was a good thing. Went in to see President Musharraf, and I said, "How are things here?," and he said: "Oh, can't you feel it? Things are lighter."

I was shocked. (Laughs.) I just told him the story, [that] we'd used the same term to describe what's going on in Pakistan. I don't know how long that window remains open and the light shines in before it fails again. And I'm afraid if Musharraf is not successful, it will fail.

That's interesting you say that, because I think I even felt some of that in Islamabad. But certainly it was shocking to me, having been there in 2002, and ... the number of women that are fully covered in Peshawar is three times greater. Billboards have women's faces painted over. Peshawar now looks like what Kabul looked like during the Taliban.

Quite a change for Peshawar, which, of course, during the Soviet war was one open market.

Yeah. So I felt heaviness there. I felt the exact opposite in that region.

You're speaking about Islamization really, which has, I think, an oppressive air to it. But if you go to Singapore, where I was about a month ago, guess what? Many more people under the veil, ... no Muslim men seen drinking alcohol. So this is a phenomenon of the world, not simply Peshawar in Pakistan. ...

Am I missing anything?

I don't think you missed you anything, but I think it's important to, when you look at Afghanistan or you look at Pakistan or you look at India, you have to see the three nations of Afghanistan, Pakistan and India interrelated, both historically, but more importantly in terms of stability. I think it's not unreasonable to say that if Afghanistan is not successful, Pakistan cannot be successful as a moderate Islamic nation. And if they're not successful as a moderate Islamic nation, then we're going to be back into the difficulties between India and Pakistan, nations which have gone to war three times since the birthing of the two nations in 1947. I guess what I'm saying is the equities in Afghanistan are enormous for the whole subcontinent, not just for us and Afghanistan.

We seem to not be doing a very good job of getting the Afghan leadership to sign on to this. I mean, they're lobbing accusations every day at the Pakistanis, blaming them for things. And the Pakistanis then see them cozying up to the Indians, and everybody just gets more and more defensive and paranoid.

Well, I would hope that somebody in the administration would connect all the dots.

But it doesn't seem to be happening.

Well, I can't speak for that. I'm an out-of-work Republican.

Well, if I can ask you as a guy who's smart about this, where are we at vis-à-vis our policy in that region? What would you say?

I think we've let Pakistan drift a little bit. I don't feel we're as secure in our relationship there as we were perhaps a year or so ago. ... I think that we all haven't paid sufficient attention to the need for an absolute success in Afghanistan.

I'll take all of that as understatement on your part, and that the situation is in fact a little more dire than that.

My personal view is that the situation in Afghanistan is a little more dire than we've seen it publicly portrayed. But I think I've adequately laid out the stakes involved, and the stakes involved are no less than the entire subcontinent.