|  |  |

As children, most of us have dreams that aren't ever realized. We imagine a

world where we are able to travel through time....or fly through the clouds.

But once in a while, some children manage to make their dreams come true.

And Ted Griffin was such child. His dream was always to capture a

dolphin/whale big enough to ride. But back then - in the 1960's - a captured

dolphin/whale was unheard of. Little was known about the killer whales except

that they were vicious predators - and probably man-eaters as well. Griffin

would spend many years and risk bankruptcy trying to prove to himself and the

world that he could ride a whale. One day, he finally did.

Ted Griffin had been so curious about marine life as a child, he would put

lead weights on his sneakers, coax someone to use a bicycle pump to push oxygen

down a tube into a diving helmet made out of an old water tank, and stay

underwater for as long as possible. He spent many days floating on the water

in Puget Sound, in Washington state -- drifting aimlessly with the tide that

pulled him away from shore and eventually carried him safely back.

Ted Griffin had been so curious about marine life as a child, he would put

lead weights on his sneakers, coax someone to use a bicycle pump to push oxygen

down a tube into a diving helmet made out of an old water tank, and stay

underwater for as long as possible. He spent many days floating on the water

in Puget Sound, in Washington state -- drifting aimlessly with the tide that

pulled him away from shore and eventually carried him safely back.

In 1954, after two years at Colorado College, Griffin returned to Puget Sound

to work in a fish hatchery. Eight years later, in 1962, he opened an

aquarium at the Seattle World's Fair. Griffin's Seattle Marine Aquarium was

a success, and it made him more determined than ever to capture a whale.

What Griffin lacked in knowledge about capturing a whale he made up for in

effort: he tracked down whales in the Puget Sound area by calling the Coast

Guard for help, carefully noting any patterns in the locations that whales were

surfacing, and even knocking on doors of waterfront residents for information

about whale sightings. But his early whale-capture trips, replete with

helicopters and a flotilla of boats, ended in failure. After three years of

trying - Griffin faced bankruptcy.

Through all of this, with the help of his brother Jim, Griffin managed to

scrape by. And his aquarium fared better after the chance arrival of two

orphaned seal pups. Ticket sales also soared after publicist Gary Boyker

suggested Griffin capture a few sharks. Still, Griffin kept hoping - someday

- he would find his whale.

In June of 1965 his prayers were answered. Fishermen accidentally caught a

22-foot killer whale in Namu, British Columbia. However, purchasing a whale

and bringing it to Puget Sound from British Columbia would prove an

extraordinary feat. After raising $8,000 - much of which was collected at

the last minute from Puget Sound store owners on a Saturday morning because

banks were closed - Griffin flew to claim his prize from fisherman William

Lechkobit on the Bounty Hunter. What Griffin didn't know was that not

only his perseverance but his physical strength was about to be tested. Once he

arrived in Namu with $8,000 in small bills --ones, five's and ten's --the

fishermen challenged him to an arm wrestling contest, the outcome of which

would determine whether Griffin could purchase the whale. Says Griffin of his

wrestling partner, "whether he gave up or not I don't know, but the deal was

done at that moment."

In his haste to purchase Namu - named after the area where he was found -

Griffin discovered he didn't quite know how to transport the 9,000 pound

killer whale 400 miles back to the Seattle Marine Aquarium. When he asked

Marineland and the Vancouver Aquarium for suggestions , they told him, "If we

knew the answer to that one, we'd have bought the whale." Griffin quickly found

welders and assembled enough people and steel to build a forty-by-forty foot

square pen held afloat by 41 bright 55-gallon orange oil drums. Nineteen days

later, thousands of Puget Sound onlookers gathered as a tugboat arrived with

Namu in the hastily constructed pen.

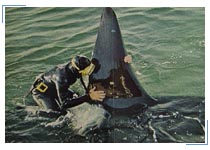

In 1965, shortly after Namu's arrival, Griffin finally rode his killer whale,

fulfilling his childhood dream. In the process, however, he also came

to befriend the whale for whom he developed "an infinity of feeling of

kinship." This close relationship, coupled with Namu's ability to follow

commands and identify Griffin even as he walked with a crowd of people, came as

a shock to most observers and contributed to a dramatic change in the world's

attitude toward killer whales. Suddenly these creatures, previously regarded

as huge sharks and shot for sport, became almost human.

For the next year - until June of 1966 - Griffin's life was a crash course in

caring for the first whale to survive more than three months in captivity.

Becoming more and more certain of the orca's amazing intellect and

communication abilities, Griffin sought to learn their language. Almost

overnight, Griffin also became a celebrity, catching the attention of the

Pentagon - which

interviewed him extensively about killer whales - and movie producers, who

eventually made the film, "Namu, the Killer Whale. "

For the next year - until June of 1966 - Griffin's life was a crash course in

caring for the first whale to survive more than three months in captivity.

Becoming more and more certain of the orca's amazing intellect and

communication abilities, Griffin sought to learn their language. Almost

overnight, Griffin also became a celebrity, catching the attention of the

Pentagon - which

interviewed him extensively about killer whales - and movie producers, who

eventually made the film, "Namu, the Killer Whale. "

However, shortly before a year had passed, Griffin lost the friend he had

struggled so hard to find. Namu drowned in June 1966 due to an anaerobic

bacteria in his digestive tract, called clostridium perfringens, that

caused severe colic. Griffin was badly shaken by the experience. Although he

continued to capture and sell whales to marine parks and aquariums until 1972,

he never found a replacement for Namu.

Today, more than thirty years after their first encounter, tears well up in

Griffin's eyes when he describes the first time that Namu echoed his words and

appeared to be saying "hi".

Griffin lives in Seattle, Washington, with his wife and owns a technology

firm.

|

|

|

Ted Griffin had been so curious about marine life as a child, he would put

lead weights on his sneakers, coax someone to use a bicycle pump to push oxygen

down a tube into a diving helmet made out of an old water tank, and stay

underwater for as long as possible. He spent many days floating on the water

in Puget Sound, in Washington state -- drifting aimlessly with the tide that

pulled him away from shore and eventually carried him safely back.

Ted Griffin had been so curious about marine life as a child, he would put

lead weights on his sneakers, coax someone to use a bicycle pump to push oxygen

down a tube into a diving helmet made out of an old water tank, and stay

underwater for as long as possible. He spent many days floating on the water

in Puget Sound, in Washington state -- drifting aimlessly with the tide that

pulled him away from shore and eventually carried him safely back. For the next year - until June of 1966 - Griffin's life was a crash course in

caring for the first whale to survive more than three months in captivity.

Becoming more and more certain of the orca's amazing intellect and

communication abilities, Griffin sought to learn their language. Almost

overnight, Griffin also became a celebrity, catching the attention of the

Pentagon - which

interviewed him extensively about killer whales - and movie producers, who

eventually made the film, "Namu, the Killer Whale. "

For the next year - until June of 1966 - Griffin's life was a crash course in

caring for the first whale to survive more than three months in captivity.

Becoming more and more certain of the orca's amazing intellect and

communication abilities, Griffin sought to learn their language. Almost

overnight, Griffin also became a celebrity, catching the attention of the

Pentagon - which

interviewed him extensively about killer whales - and movie producers, who

eventually made the film, "Namu, the Killer Whale. "