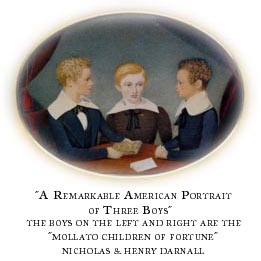

Because of their elegant attire and the upper class setting in which they are so formally posed, the early 19th century miniature portrait of these two young men of color is a rather remarkable one. What makes it even more so is the presence of the third youth, who is white. For despite our racial history, it is quite clear that neither of the two companions he is portrayed with should be mistaken as his social inferior. Because of their elegant attire and the upper class setting in which they are so formally posed, the early 19th century miniature portrait of these two young men of color is a rather remarkable one. What makes it even more so is the presence of the third youth, who is white. For despite our racial history, it is quite clear that neither of the two companions he is portrayed with should be mistaken as his social inferior.

Clues to the possible identity of the sitters in this miniature measuring 4" across, can be found in the biography of Paul Cuffe. In the early part of the 19th century, Captain Paul Cuffe was easily the most famous man of color in the U.S. He had returned to Westport, Massachusetts in 1812, after an exploratory visit to the newly-created settlement of Sierra Leone on the west coast of Africa. Cuffe's trip had been of great interest to the Abolitionist movement both in the U.S. and Britain. There were expectations that Cuffe, a shipping magnate, could help anti-slavery activists realize the dream of a refuge for former slaves from the racism that seemed to be rising exponentially with the growing success of the Abolitionists' campaign.

Biographical sketches and newspaper accounts of the welcome Cuffe received on a side trip to England were not only picked up by the American press but since they were carried verbatim, probably exposed the U.S. public to a far more liberal treatment and description of a black subject than it had ever read before. The high point of all this attention came when Massachusetts state representatives arranged a meeting for Cuffe with President Madison, thus making Cuffe the first black to be officially entertained in the White House.

As a result of such extensive coverage and the controversy Cuffe provoked in Congress a year later trying to get a bill passed to support his African resettlement cause, he came to be seen as something of an authority on African American affairs and was approached for his advice on any number of related issues. One such request was found among Paul Cuffe's correspondence and it is of special interest to us for it pertains to the above portrait miniature.

In a letter dated May 1, 1814, Cuffe writes that advice had been asked of him:

"...Concerning 2 boys of Colour from 10 to 11 years of age. From information they are Mollato Children of fortune. The gentleman that rote me rote from Anapolis Maryland and states that from predejues of oppression he wished to have them the 2 boys removed into the northern States and placed in the Care of a pious Character to be educated Suitable to enjoy the improvements of their fortunes...The Gentleman that rote me inquires to be informed whether any eligible situation could be procured in a public seminary where they could be properly attended to. Also the expense of boarding teaching clothing and the whole cost of their education..."

The "Gentleman that rote" Capt. Cuffe was none other than John Francis Mercer, former governor of Maryland. However, whether from a need to protect the privacy of two such vulnerable minors or the honor of their rather influential white family, no mention of who they were appears in the subsequent letters. It is only from relevant documents extant in the State Archives of Maryland that we are able to piece together the identity of these two young men.

Considering the particularities of this situation, the records that should first be consulted are those of the Orphan's Court. However, because guardians are not listed in the index to those volumes dealing with the early 19th century Maryland, this task could have proved extremely daunting. Gratefully, it is an abstract in Helen Cotterall's "Judicial Cases Concerning American Slavery" that allows us to circumvent this problem. Although the date of the pertinent case, "Le Grand vs. Darnall" is January 1829, the opening paragraph reads,

"Bennet Darnall...1810...executed his last will...and thereby devised to his son [Nicholas], the appellee, several tracts of land in fee, one of which was called Portland Manor...The mother of Nicholas Darnall was the slave of the testator, and Nicholas was born the slave of his father, and was between ten and eleven years old...at the death of the testator..."

According to the abstract, the death of Bennet Darnall occurred in 1814. This date matches with that of Capt. Cuffe's correspondence relating to the two boys. Moreover the identity of the second son appears in the following paragraph:

"Four respectable witnesses of the neighborhood...all agree in their testimony, that Nicholas was well grown, healthy and intelligent, and of good bodily and mental capacity: that he and his brother Henry could readily have found employment, either as house servant boys, or on a farm, or as apprentices...The testator devised to each of them real and personal estate to a considerable amount..."

In the summary of this case which is essentially about a slave's right to inherit, two names appear that confirm that Nicholas and Henry Darnall are the young men in whose lives Capt. Cuffe had become involved. Not only is former Governor Mercer one of the"four respectable witnesses," but mention is also made of a Benjamin Tucker of Philadelphia. It is in a letter of Cuffe's to Mercer dated "7 mo 6th 1814" that we first hear of him.

"...I was glad that thee fell in with Benj. Tucker. He is one who I trust the Verry utmost Confidence may be placed in. I am truly Glade the Little Boys have Been placed in thy Care. I believe thay are as well placed at Present as thay Can be. I beg to be excused if I should take the liberty at times to Enquire of Benjamin Tucker after the Boys wellfar..."

In another letter, some eight months later Cuffe explains who he is.

"...The 2 boys are at school 7 miles out of Philadelphia and information can be obtained concerning the boys by inquiring of Benjamin Tucker School master Phila..."

The fact that so much effort had been expended to secure an education for these boys must have left a rather chilling impression on Paul Cuffe. They had inherited an estate that must have been appreciably larger than the one Cuffe himself had acquired, but neither their wealth or their descent from one of the most influential families of Maryland was a guarantee that the rights and benefits which their father had gone to such precautions to secure for them would be respected. In his letter to Captain Cuffe, Governor Mercer had in fact stated that

"...in consequence of the deep rooted and indomitable prejudices of the our country, their situation here is surrounded with embarrassment and their wealth accompanied by their color is a constant source of the most malevolent jealousy, amongst the decay and profligate of both complexions."

Considering the social prominence of the Darnall family to which these "Molatto children of fortune" belonged, the possibility that they are two of the sitters in the miniature above is an intriguing one. The miniature appeared as an advertisement for the firm of Earle Vandecar in the January 1997 issue of the Magazine Antiques. Since neither an inscription or a provenance accompanies the piece, our only opportunity for making such an attribution will have to rely solely on deduction. The key to this little puzzle therefore, must not only be a plausible identity for the white child in the portrait, but an appropriate reason for his inclusion, as well.

A work on the "Darnall, Darnell Family" by Harry Clyde Smith published in 1979 could prove helpful. Besides duly listing Nicholas, Henry and two other illegitimate sons Bennet Darnall sired, the author attempts to include the property divisions that are made in each generation. According to Smith, it appears that along with Nicholas and Henry, a third member of the Darnall family also had special claims to a portion of the Darnall estate known as Portland Manor and which had devolved to Bennett by right of succession. From the dates available, we know that he was about five or six years older than Nicholas. Smith's note that what he had been bequeathed was only for"a part" and used "as a summer home" might be a clue since the Le Grand vs. Darnall case of 1829 had been instigated by Nicholas to specifically test his rights to Portland Manor. As sketchy as it is, Smith's work does not explain why a great nephew had inherited a portion of Bennett Darnall's personal property even if comparatively smaller than what he left his sons.

The answer to this question might perhaps, be found in the name of the legatee. Christened Richard Bennett Darnall, it would not be unreasonable for us to presume that he was named for his great uncle - who, in turn, had been named for his mother's grandfather, Governor Bennett of Virginia. What we might tentatively conjecture, therefore, is that Bennett was Richard Bennett's godfather and that his title to Portland Manor had been a baptismal present. True, Richard Bennett's younger sibling, Henry, also carried Bennett as a second name but he was probably named in honor of Bennett's brother, Henry Bennett. As Bennett was the only member of the Darnall family to be given this surname for his first, the name, Richard, would, in all likelihood, have been understood, as well, since that was the name of the Virginia Governor they obviously hoped posterity would remember as yet another historically important ancestor of theirs.

Interestingly, Smith relates that Richard Bennett's eldest brother, Archibald, severed all communications with his family and even left Maryland because of a major disagreement. Since Portland Manor would have devolved to him had not Bennett bequeathed this rather impressive estate to his illegitimate sons, it would not be unreasonable for us to guess that the cause of so serious a break between Archibald and his kin was the Darnalls' decision to honor Bennett's will.

If these assumptions are correct, we then have a third sitter whose appearance in this miniature fits our requirements - on still another level. For even though a first cousin once removed from Nicholas and Henry Darnall, Richard Bennett Darnall was also a son of Bennett's - a spiritual one. Those depicted in this group portrait, therefore, are the three heirs of Bennett Darnall, the inheritors of Portland Manor, the once proud possession of the Darnall dynasty in Maryland.

The Darnall Family

Philip Darnall was the first of the family to immigrate to this country; he was born in 1604. A relative and the secretary to George Calvert who would later be created first Lord Baltimore, Philp became one of the wealthiest men in Maryland. Before his arrival in the Americas, however, Philip Darnall had accompanied George Calvert on an extended diplomatic mission to France where they were both converted to Roman Catholicism. His son, Col. Henry Darnall, 1645-1711, acted as Proprietory's Agent to the second Lord Baltimore and served as his Deputy Governor. Harry Clyde Smith comments that

"Henry Darnall was both affluent and influential. He owned much land and many slaves. At his death, he bequeathed some thirty thousand acres of land...A devout Roman Catholic, he sent his sons to Jesuit schools in Europe - one of the inciting factors in the "Protestant Revolution," following which Henry maintained secret quarters in his home, with all equipment necessary for observing the rites of his religion."

Through his daughter, Mary, Henry Darnall was the great grandfather of Charles Carroll, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. Through his grand-daughter, Eleanor, he was also the great-grand father of John Carroll, Bishop of Baltimore and the first Roman Catholic bishop of the country. Considering his importance to the history of the nation, another such relationship that cannot be overlooked because of its racial irony is that of the Darnalls to Roger Brook Taney, the supreme court justice who handed down the infamous Dredd-Scott decision. Not only did Henry Darnall and his son Philip marry Brooke women but so did the Judge's father, his great, grand father and his great, great, grand father. Besides being cousins several times over to the Chief Justice, Bennett's mulatto sons even had a Brooke as an uncle.

All odds are that neither Nicholas or Henry Darnall left any descendants. The elder of the brothers spent the rest of his life in Philadelphia never married, perhaps too confused by issues of class and racial identity to do so. In the 1850 census, for instance, he is living next door to one of the richest white men in the Bristol district of Philadelphia - residing with a young family of Irish immigrants - and the only person of color in the vicinity. And because the only mention of Henry in the Le Grand vs. Darnall case is in reference to his legal status at the time of his father's death in 1814, we are left with the impression that he was dead by 1829.

It is quite possible, however, that a sister of theirs did marry. Although Smith identifies her as the grand-daughter of Nicholas Lowe Darnell, a brother of Bennett's, the International Genealogical Index for North America lists Henrietta Maria as the daughter of Bennett Darnall and Susan. And it is this Susan who is the slave mother of Nicholas and Henry.

Susan, the Mother of Nicholas and Henry

From a couple of other cases cited by Helen Cotterall, it might be possible to reconstruct a genealogy for Susan, as well, even if not as long as the Darnall's. With the recurrence of the name, Susan, as a clue, it is not inconceivable that she could prove to be a descendant of Ann Joice who had come to Maryland in about 1680 with Lord Baltimore. Because Baltimore had brought her from Barbados via England, her family later attempted to use the Mansfield decision of 1772, to claim their freedom from the Darnalls. As Joice's children and grand children are all referred to as 'mulattos,' we should not be surprised if they were not actually a part of the 'extended' Darnall family. This could explain how, even though in the final analysis it was a futile one, they were able to mount such a sophisticated defense for themselves in court. Interestingly enough, Bennett had succeeded to Portland Manor after two older brothers had died and who like himself had never married but left legacies to support children they had both fathered with slave women on their estate.

According to both Smith and the IGI entry, Henrietta Maria Darnall married John Meeks in 1810. The Meeks social standing in Anne Arundel County during this particular period in time has yet to be determined. But according to a surveyor's report in Vol. 33, 1938 of the Maryland Historical Magazine, they had been the proprietors of a thousand-acre estate by the name of Chichister in 1700. If we accept the IGI data concerning Herietta Maria, it would suggest that despite laws of inheritance favoring male heirs, Bennett Darnall had succeeded in providing for his daughter in the traditional manner - a suitable marriage. It would, of course, also raise the question as to whether the size of his slave daughter's dowry had, in any way, been influential in persuading John Meeks to marry her. On the other hand, it would also make for an interesting example of the subtleties of gender politics. For unlike the Gibsons or the Pendarvises of SC (discussed elsewhere on this web site) whose color had not prevented their men from becoming leaders of the political establishment just a couple of generations earlier, the social prospects for the Darnall boys by this particular time in American history were next to nil.

Besides the dramatic increase in free blacks after the Revolution, what undoubtedly contributed to the antagonism towards his two young wards - which Governor Mercer found so appalling - was the hysteria brought on by the War of 1812. Many blacks had sided with the enemy during the country's struggle for its independence from Britain. Assaults against people of color became so prevalent that mounted troops had to be detailed by the mayor to protect them from the white mobs in Baltimore.

The Painter

It would be a mistake to attribute this little miniature portrait to the African American artist, Joshua Johnson of Baltimore, despite the understandable temptation to do so. Besides receiving commissions from a number of families related to the Darnalls, Johnson also was asked to do a portrait of Daniel Coker, the leader of the African Institute which had been established in Baltimore by none other than Captain Paul Cuffe. But even though one could easily point to certain stylistic similarities between examples of Johnson's work and the miniature, there are a number of idiosyncrasies in his technique that identify him which are not evident here. Perhaps, the most critical of which is how he rendered eyes. As his biographers, Carolyn Weekly and Styles Colwill put it,

"...we observe some evidence of a peculiar slant of the upper eyelids of Johnson's sitters...The manner in which the sitters' eyes are drawn...is in fact, one of the most telling characteristics of his work."

From the way in which this particular feature is handled in the portrayal of Richard Bennett Darnall, the only one of the three boys who faces the viewer, it is fairly obvious that this is not a piece by Joshua Johnson. The identity of the miniaturist will have to be sought from among such contemporaries of his as Dominic Boudet and Lewis Pease who also worked in Maryland. Like Johnson's rendering of eyes, perhaps one clue will be the artist's treatment of mouths or, more accurately, teeth. Remarkably different from the invariably rigid, tight lipped formality with which sitters were posed at the time, the artist has not only depicted Richard Bennett's mouth in a relaxed smile revealing three of his upper front teeth but as what must have been regarded as something of a feat at the time, considering the scale of the piece, he or she has clearly but very realistically delineated the separation between each tooth, as well.

From whatever the denominational viewpoint, whether the Catholicism of the Darnalls or, though less defiant, the quiet but persistent Quaker faith of Capt. Cuffe and so many of the associates he called on to help Governor Mercer place his mulatto wards, it is not inconceivable that the sentiment expressed in the miniature was meant to be interpreted as religiously abolitionist and a didactic one at that. Not only from two disparate lines of the family, but even more importantly - of two different races - the three young men portrayed are, through the sacrament of Baptism, nothing less than brothers in Christ.

|