Religion in The Roman World

An essay by Marianne Bonz describing the myriad of religious options available in the Roman Empire.Bonz is managing editor of Harvard Theological Review. She received a doctorate from Harvard Divinity School, with a dissertation on Luke-Acts as a literary challenge to the propaganda of imperial Rome. She has published several articles on the status of Jews in the Greek province of the Empire and on the developing religious message of the Roman emperors.

Early Christian preachers such as the Apostle Paul brought the gospel about Jesus Christ to an empire already crammed full of deities. The citizens of the Roman empire and, within certain limits, even its rulers were extremely tolerant of foreign gods. The oldest and most accepted group of foreign deities were the gods of ancient Greece. These gods had made their home in the Roman world at an early time, along with Greek art and literature. Some of these Greek gods shared Roman names and acquired some Roman characteristics. But many others were simply accepted as they were.

The Gods of Mount Olympus

According to Greek mythology, when the sons of Cronus divided the universe among themselves, Zeus received the regions above the world, Poseidon claimed the vast regions of ocean as his domain, and Hades was given the regions beneath the earth. But, except for Hades, who preferred his underworld domain, it was agreed that the clouds above Mt. Olympus should be the common dwelling place of all the gods.

Assembled on Mt. Olympus, the gods formed a kind of extended family, an exclusive society, with its own laws and hierarchy. First came the twelve great gods and goddesses: Zeus, Poseidon, Hephaestus, Hermes, Ares, and Apollo; Hera, Athene, Artemis, Hestia, Aphrodite, and Demeter. Not part of this original twelve but placed with them were several other deities, the most important of whom are Helios and Selene (the sun and the moon) and Dionysus.

As the first among equals, the mighty Zeus ruled over this frequently contentious and somewhat dysfunctional Olympian family. These gods were thought of as resembling people, except they were much bigger, more powerful, and usually more beautiful. Like mortals, they experienced emotions, such as love, hate, anger, and jealousy. But unlike mortals, their bodies always healed from the wounds of war or the ravages of disease, and they never aged. The gods also possessed the ability to change themselves into all manner of disguises, including those of animals and inanimate objects.

Zeus: Even in the ancient Greek poems of Homer and Hesiod, Zeus was the ruler of the gods, the most powerful and the most wise. But in these early days, Zeus also was guilty of numerous sexual indiscretions with both goddesses and mortal women. These liaisons resulted in the birth of a number of demi-gods and heroes, for whom the Greeks also established cults. Despite his wisdom and majesty, this early Zeus could also be petty, self-indulgent, and occasionally cruel.

By the first century before the common era, however, his identity had merged with the more serious Roman god Jupiter. And this new Zeus/Jupiter was to become the supremely just, powerful, and even benevolent protector of the Roman empire. His will for his earthly subjects was frequently equated with divine providence or the unfathomable workings of Fate.

Apollo: Not to be confused with the sun itself, which was represented by a special divinity, Helios, Apollo was nonetheless a solar god. Because the Mediterranean sun's rays strike the earth like darts, Apollo was thought of as an archer-god, whose arrows could either wound or heal. He was also the god of song and the lyre, as well as the god of divination and prophecy. His sanctuary at Delphi was one of the most sacred places in the Greek world for revelation and interpretation.

Apollo: Not to be confused with the sun itself, which was represented by a special divinity, Helios, Apollo was nonetheless a solar god. Because the Mediterranean sun's rays strike the earth like darts, Apollo was thought of as an archer-god, whose arrows could either wound or heal. He was also the god of song and the lyre, as well as the god of divination and prophecy. His sanctuary at Delphi was one of the most sacred places in the Greek world for revelation and interpretation.

In the Iliad, Homer's epic narrative of the Trojan War, Apollo allied himself with the Trojans. Since Rome subsequently claimed the Trojans as their ancestors, it is perhaps not surprising that Rome's first emperor, Augustus, placed his reign under Apollo's special protection. To reinforce his association with the god, Augustus built a sanctuary for Apollo next to his palace on the Palatine hill in Rome. Later, the emperor Nero, who fancied himself a musician, would also claim a special association with Apollo.

Artemis: Artemis was the twin sister of Apollo. Their mother was Leto, one of the many goddesses seduced by Zeus. Like Apollo, Artemis was a goddess of the hunt. She is usually depicted as a kind of tomboy in short tunic, carrying a bow and arrows. Also like her brother, who was associated with the light of the sun, Artemis was associated with the light of the moon. As such, in some regions she was also considered the protectress of the tombs of the dead.

Artemis: Artemis was the twin sister of Apollo. Their mother was Leto, one of the many goddesses seduced by Zeus. Like Apollo, Artemis was a goddess of the hunt. She is usually depicted as a kind of tomboy in short tunic, carrying a bow and arrows. Also like her brother, who was associated with the light of the sun, Artemis was associated with the light of the moon. As such, in some regions she was also considered the protectress of the tombs of the dead.

Very different in origin and appearance is Artemis of Ephesus, whose immense temple came to be known as one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, and whose ardent worshipers form the backdrop for one of the most dramatic encounters in the Book of Acts. This Artemis was a goddess of fertility and fecundity, who probably traveled to the area in and around Ephesus from barbarian regions further east.

Aphrodite: The daughter of Zeus by yet another minor female deity, Aphrodite was the personification of female beauty. Although all of the Olympian goddesses were beautiful in their way, only Aphrodite exuded charm and seduction. Although she may have originated as a fertility goddess, she is known primarily as the goddess of love. Her devotees ranged from unmarried girls and widows, seeking to obtain husbands, to courtesans, some of whom served in her temples. It is perhaps no surprise therefore that sailors were among her most frequent worshipers!

In the Roman world she was also identified with the goddess Venus, the beautiful and seductive goddess who was the mother of Aeneas, the founding hero of Rome according to legend. But since Julius Caesar, his nephew the emperor Augustus, and all of the Roman emperors down to Nero traced their own ancestry back to Aeneas and through him to Venus, her cult emphasized romantic, marital, and especially maternal love.

Demeter: Of the twelve original Olympian deities, Demeter was probably the one who most affected the lives and fortunes of common people. She was the goddess of fertility and of the fruits of the harvest. She was worshipped throughout the Greek world and remained important to her Greek subjects even in the Roman imperial era. She had the reputation of being accessible to the needs of mortals, on whom she bestowed the benefits of the earth's abundance.

Her primary sanctuary was at Eleusis, in the country beyond the outskirts of Athens. And her cult centered on the reenactment of a story by means of which the Greeks explained the mysteries of the agricultural seasons--how the earth's vegetation seemed to die in winter, only to be reborn again every spring.

In addition to two yearly festivals in which the end of the harvest and the renewal of the planting were commemorated, a major festival was celebrated every five years. The principal object of this festival was the public veneration of Demeter and, for those who qualified, the celebration of her mysteries. Although Romans generally were not admitted to these secret rites, the goddess wisely permitted a few. We know of at least two emperors who were initiated into her mysteries and who supported her cult with material gifts.

Since the proceedings of these mysteries and their rituals remained secret, historians do not know exactly what transpired. It is known, however, that those who participated were granted some assurance of the continued favor of the goddess, both in this life and the next.

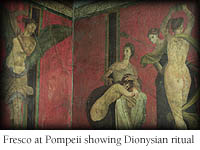

Dionysus: Although not one of the original Olympians, the cult of Dionysus was very old and was celebrated throughout the Greek world and beyond. As the god of the vine and of the pleasures of its cultivation, his cult became associated with that of Demeter at an early time. As with Demeter, his devotees ranged the entire spectrum of the social scale. Likewise, his cultic observance ranged from dignified ceremonies and parades to orgiastic celebrations and festivals.

Dionysus: Although not one of the original Olympians, the cult of Dionysus was very old and was celebrated throughout the Greek world and beyond. As the god of the vine and of the pleasures of its cultivation, his cult became associated with that of Demeter at an early time. As with Demeter, his devotees ranged the entire spectrum of the social scale. Likewise, his cultic observance ranged from dignified ceremonies and parades to orgiastic celebrations and festivals.

Later Rome, fearing that these festivals would lead to civil unrest, attempted to suppress his cult, but it met with very little success. Although the Romans could not curtail the immense popularity of Dionysus, the god's appearance and the legends surrounding his worship did change dramatically over time.

Even though fairly early in his history Dionysus's appearance changed from that of a mature, bearded man of a decidedly rustic quality to a long-haired and somewhat effeminate adolescent with exotic attributes, throughout most of his history his essential character remained that of a charming rogue. He was depicted as the god who brought the joys and ecstasies of the vine, as well as the fruits of civilization, and not only to Greece but also to far-away India and Egypt. But Dionysus also could reduce even people of consequence to madness, if they crossed him.

During the Roman period a new legend developed concerning Dionysus, one that offers intriguing parallels to Christianity. According to this legend, Dionysus was killed while battling the enemies of Zeus. His body was dismembered, but Zeus restored him to immortal life. Henceforth, according to the late first-century Greek philosopher Plutarch, Dionysus became a dying and rising god, and a symbol of ever-lasting life.

For all of their majesty and beauty, however, the Olympian deities seemed not to care about the lives of ordinary human beings. And by the arrival of the common era, with the exception of Demeter and Dionysus, these gods had become largely ceremonial. The devotion of the average Greek or Roman centered on gods of lesser rank, gods who had once been mortal and who, therefore, understood the sufferings of mortals--gods who cared.

Miracles and Healing in the Roman World

In Matthew's gospel, Jesus' birth is heralded by the heavenly portent of a star rising in the East, which guides certain wise men (or astrologers) who travel from a distant land to Bethlehem to see the future king (Matt 2:1-2). In all of the gospels Jesus performs numerous healings, and on several occasions he even brings the dead back to life. And in the Book of Acts, a vision of the risen Jesus appears to Saul on the road to Damascus (Acts 9:1-7). As a result of this encounter, Saul is converted and eventually becomes Paul, who devotes the rest of his life to the service of Christ.

Although all of these religious claims seem remarkable to the modern reader, none of them would have astounded the average citizen of the early Roman empire. Stories of heavenly portents, miraculous healings, mystical visions, and even resurrections were told about a number of demi-gods or heroes. In fact, a number of supernatural phenomena were even attributed to certain philosophers and emperors.

Omens and Portents: Roman historians such as Suetonius and Tacitus frequently reported the occurrence of miraculous omens or portents regarding the emperors, particularly at the beginning or end of their reigns. Because Rome placed its rulers at the summit of human society, it was believed that they served as mediators for the will of the gods on earth. Accordingly, the appearance of omens, for good or ill, was the means by which the gods could signal the working of their will in human affairs.

After the death of Julius Caesar, Suetonius (Lives of the Caesars: Julius 88) reports that at the funeral games held in his honor "a comet shone for seven successive days, rising about the eleventh hour, and was believed to be the soul of Caesar, which had been taken into heaven." But it was Julius Caesar's adopted son, the immensely popular and widely-revered emperor Augustus, who generated the most stories of this type. According to one story, Augustus's mother was worshipping in the temple of Apollo when she fell asleep and was impregnated by the god (Suetonius Lives of the Caesars: Augustus 94). Another story also attested to Augustus's unusually close relationship to Apollo, the god of prophecy, by crediting the emperor with having divined beforehand the outcome of all of his wars (Suetonius Lives of the Caesars: Augustus 96).

Miracles: In the first century of the common era, renowned men could also be credited with having performed miracles. The popular emperor Vespasian (the former Roman general who had befriended the Jewish historian Josephus during the First Jewish Revolt) was credited with having performed several miracles. According to stories recorded by the Greek historians Dio Cassius and Tacitus, Vespasian worked several healing miracles, while visiting the shrine of Sarapis in Egypt. Among these miracles, Vespasian is credited with healing a blind man and restoring another man's crippled hand (Tacitus Histories 4.81).

But miraculous powers were not limited to emperors, or even to people from the empire's social and political elite. Miracles were a sign of a special relationship between the gods and particular individuals. People who were thought to possess great wisdom or virtue were also frequently credited with performing miracles.

One interesting example of a wonder-working, itinerant philosopher is that of Apollonius of Tyana. Apollonius was a late first-century follower of the famous Greek philosopher, Pythagoras, whom some believed had become a god. Having renounced his possessions and worldly position in virtuous pursuit of divine wisdom, Apollonius was reputed to have led a disciplined and rigorously ascetic life.

According to his later biographer, Philostratus, Apollonius possessed extraordinary gifts, including innate knowledge of all languages, the ability to foretell the future, and the ability to see across great distances. Apollonius's possession of divine wisdom also endowed him with the ability to heal the sick and demon-possessed, and Philostratus narrates the miraculous quality of a number of these cures and exorcisms.

What all of these stories of wonder workers have in common is that (in contrast to magic, which is performed by charlatans for personal profit) miracles are performed by exceptional human beings, in the service of a god, for the good of other people.

In addition to mere human beings, who were so favored either because of their extraordinary power or their extraordinary wisdom and virtue, the world of the early Roman empire was also inhabited by another group of individuals who could serve as intermediaries between the gods above and the world below. These were the demi-gods or heroes, individuals of mixed parentage (human and divine). They were usually credited with possessing extraordinary powers, while also possessing great understanding of and compassion for the pain and suffering of ordinary human beings.

In general, their demi-god status is expressed in the fact that they live as mortals; but when they die, they retain their fully vigorous human appearance, as well as their former powers. Because of their unique status and qualities, in the popular imagination these demi-gods were frequently regarded as protectors. In the world of the first century, Herakles (Hercules) and Asclepius were two of the most widely worshipped of these protector or "savior" gods.

Herakles: According to Greek legend, Herakles was the son of Zeus by a mortal woman of noble lineage, whose name was Alcmene. Zeus's vengeful wife, Hera, attempted to kill the infant Herakles by placing serpents in the cradle where he and his twin brother slept. But Herakles strangled the snakes, thus saving himself and his twin.

In addition to semi-divine parentage and birth in difficult circumstances, another common feature of the lives of demi-gods is that they encounter ignominy or great misfortune, which they must either overcome before death or resolve through death. After he was grown and married, Herakles was struck with a deadly madness and, mistaking his own wife and children for those of a bitter enemy, he killed them. It was in atonement for this terrible crime that he performed the twelve superhuman labors that rid the world of terrifying monsters and brought new security to the world's inhabitants.

Because of his superhuman strength, Herakles was the patron of athletes, and sanctuaries honoring him adorned virtually every gymnasium throughout the Greco-Roman world. But his most important role was that of powerful patron and protector of human beings and gods alike.

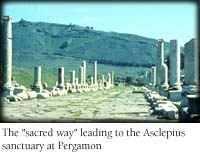

Asclepius: The son of Apollo by a mortal woman, Asclepius was taken by his divine father at birth and apprenticed to a wise centaur (a mythical creature, half man and half horse). This centaur, whose name was Chiron, taught Asclepius the healing arts so that he could reduce the sufferings of mortals. With his miraculous cures, Asclepius quickly earned great fame. Motivated by compassion, he even succeeded in restoring the dead to life. But this proved his undoing. Hades complained to Zeus that if this were allowed to continue, the natural order of the universe would be subverted. Zeus agreed and struck Asclepius down with a thunderbolt. In some versions of the story, Asclepius was transformed into a star after his death.

Asclepius: The son of Apollo by a mortal woman, Asclepius was taken by his divine father at birth and apprenticed to a wise centaur (a mythical creature, half man and half horse). This centaur, whose name was Chiron, taught Asclepius the healing arts so that he could reduce the sufferings of mortals. With his miraculous cures, Asclepius quickly earned great fame. Motivated by compassion, he even succeeded in restoring the dead to life. But this proved his undoing. Hades complained to Zeus that if this were allowed to continue, the natural order of the universe would be subverted. Zeus agreed and struck Asclepius down with a thunderbolt. In some versions of the story, Asclepius was transformed into a star after his death.

Asclepius was an immensely popular god, originally in Greece but later also in Rome. By the fourth century before the common era, he had established a number of sanctuaries in Greece, the most important ones being in Cos and Epidauros. Early in the third century BCE, his cult was brought to Rome after the city had been struck by a plague. Asclepius's medical knowledge and divine healing powers fostered two distinct traditions within the Greek world. On the one hand, he served as a divine mentor to the doctors who treated patients at his sanctuary at Cos. On the other hand, at the sanctuary of Epidauros, the god performed miraculous cures in response to the direct petitions of suppliants.

In the early Roman imperial era, Asclepius assumed an even greater religious importance. He had become a savior god. The physically or emotionally afflicted received long-term care and guidance at his sanctuaries, and in return they devoted themselves to his worship and service.

The most famous of devotee of Asclepius during the Roman imperial period was the rhetor and sophist (professional public speaker) Aelius Aristides. Having just embarked on his public career, Aristides was stricken by a complete physical and mental breakdown. After seeking the help of another god to no avail, he visited the shrine of Asclepius in his adoptive city of Smyrna.

During this visit, the god appeared to Aristides in a dream-vision, and this encounter changed his life. Asclepius not only prescribed treatments for his chronic bouts of illness, the god also offered guidance for the conduct of all aspects of his life. Thereafter, Aristides placed himself and his career under the god's protection, making numerous extended visits to the renowned Asclepius sanctuary in Pergamon. In his autobiographical narrative of his numerous encounters with the god, Aristides reveals his special relationship with Asclepius by most often addressing the god as "Savior."

Other Popular Savior Deities of the Early Roman Imperial Era

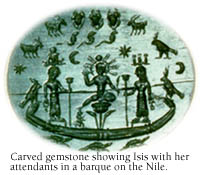

Isis: Even though the oldest and most distinguished cults of the Roman imperial period had originated either in ancient Greece or in Rome itself, a number of foreign cults imported from the more recently conquered territories of the empire had also developed large and enthusiastic followings. This was especially true of the Egyptian cult of Isis, which, along with the relatively new cult of her consort Sarapis, together with her son Horus and an assortment of lesser deities of exotic character, had migrated first to Greece and then to Rome.

Isis: Even though the oldest and most distinguished cults of the Roman imperial period had originated either in ancient Greece or in Rome itself, a number of foreign cults imported from the more recently conquered territories of the empire had also developed large and enthusiastic followings. This was especially true of the Egyptian cult of Isis, which, along with the relatively new cult of her consort Sarapis, together with her son Horus and an assortment of lesser deities of exotic character, had migrated first to Greece and then to Rome.

Originating in conjunction with her former husband Osiris as the personification of the divine power of the Pharaohs of ancient Egypt, Isis was worshipped continuously for thousands of years, before achieving her greatest renown in the early Roman empire. During this final period, her cult presented one of the most formidable and enduring rivalries to early Christianity.

According to the ancient Egyptian legend, Osiris succeeded to the throne of Egypt when his divine father, Geb, retired to the heavens. His sister, Isis, became his queen. Osiris brought agricultural abundance to Egypt and introduced the arts of civilization. After some years of peaceful rule, he was cruelly murdered. But Isis recovered his body and, with the aid of Thoth (Wisdom) and Anubis (Guide of dead souls), she succeeded in restoring Osiris to life. Once resurrected from death, Osiris could have returned to rule over Egypt. Instead he relinquished his throne to his son, Horus, preferring to rule over the kingdom of the dead.

Although in the myth of this early period, Isis played only a minor role, she gradually acquired an impressive list of attributes for which she was widely venerated. In the third century before Christ, Egypt was ruled by the Greek successors of Alexander the Great. It was they who substantially transformed the cult of Isis, replacing Osiris with a new divinity, Sarapis (an amalgamation of Osiris and another Egyptian god, Apis). By taking this ancient Egyptian cult of the Pharaohs and making it their own, the new rulers sought to reconcile the land and its people to Greek control.

Gradually Isis and Sarapis divided between them all the powers of the universe. Sarapis, like the Greek god Zeus, with whom he was often identified, represented a divine majesty of universal scope, encompassing rulers and nations. But Isis was a savior and protector in a far more personal way. Gradually assimilating the most important characters and attributes of a number of goddesses native to Greece, her benefactions became virtually without limits.

Isis was worshipped as the divine impetus for the establishment of justice and the laws of human society. She was also frequently associated with the benefits of agriculture and the harvest. She was known to guide women through the dangers of childbirth. In one of several surviving hymns, written in the final centuries before Christ, Isis is credited with a knowledge of the nature of all things. In another, she is venerated as the queen of every land.

This exceptional adoration is closely linked to her proven record of benefactions on behalf of ordinary people. Archaeologists have discovered a number of inscriptions in which a grateful worshiper has detailed the many gifts bestowed by the goddess, including healings and miraculous rescues from the perils of sea voyage.

Like Christianity, Isis's cult was spread by her followers, primarily to the port cities of the empire, by means of its trade and navigation routes. Also like Christianity, the cult of Isis grew from the bottom up. By the dawn of the common era, her cult had become so widespread among the masses of the Roman empire that the emperor Augustus and his immediate successors were unable to suppress it, and they eventually gave up the attempt.

By the time of the destruction of Jerusalem and the writing of the Gospel of Mark, Isis had even become a patron deity of the Roman imperial family. Her cult, with its mysteries that promised salvation to initiates, remained widely popular well into the early Christian era. In the following quotation from a Greek novel of the second century, CE, it is the goddess herself who speaks to an initiate who has earnestly sought her favor:

"Behold, Lucius. . . moved by your prayer I come to you--I the natural mother of all life, the mistress of the elements, the first child of time, the supreme divinity, the queen of the underworld, the first among those in heaven--I, whose single godhead is venerated all over the earth under manifold forms, varying rites, and changing names. . . . Queen Isis.

"Behold, I have come to you in your calamity. I have come with solace and aid. Away then with tears. Cease to moan. Send sorrow fleeing. Soon through my providence shall the sun of your salvation rise." (Apuleius, Metamorphoses 11.5)

Religion and the Roman Emperors

In the last century before the common era, the Greek cities had fallen prey to corrupt Roman administrators and sporadic local insurrections, as the power struggles between rival Roman factions consumed the remaining vigor of the dying Roman republic. All of these struggles came to an end when Octavian (who, as emperor, was given the name Augustus) defeated the forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the battle of Actium.

With the advent of the reign of Augustus in 27 BCE, life in the provincial cities of the Greek East became far more stable and prosperous than it had been for a very long time. The relief of the subject peoples was immense, and a number of the cities issued decrees honoring the new emperor as the earthly appearance of a benevolent god: "Providence. . .by producing Augustus [has sent] us and our descendants a Savior, who has put an end to war and established all things. . . ."

With the advent of the reign of Augustus in 27 BCE, life in the provincial cities of the Greek East became far more stable and prosperous than it had been for a very long time. The relief of the subject peoples was immense, and a number of the cities issued decrees honoring the new emperor as the earthly appearance of a benevolent god: "Providence. . .by producing Augustus [has sent] us and our descendants a Savior, who has put an end to war and established all things. . . ."

Such a response was not without precedent. Since the time of Alexander the Great, the Greeks had been accustomed to giving their rulers divine honors. But with the advent of Augustus, the situation was different. As historian S. R. F. Price observes, the decrees honoring Augustus "make explicit and elaborate comparisons between the actions of the emperor and those of the gods."

Furthermore, the worship of Augustus was not tied to specific benefactions or civic improvements. Rather, Augustus was worshipped throughout the empire as the benefactor of the whole world. The outpouring of praise, gratitude, and affection for this first emperor, who reigned at the time when Jesus was born, was undoubtedly genuine.

It was Augustus's virtually unchallenged prestige and popularity that provided the impetus for establishing a cult of the emperors. And this cult, once established, provided continuing support for the imperial governing authority. Accordingly, from the very beginning, the cult of the emperors was a complete merging of religion and politics.

The Role of the Gods in the Care of the Empire and Its Ruler: With the exception of a few gods and goddesses who ministered to the private needs of individuals, the role of the Olympian deities was to care for the various aspects of the natural world and of human society. For example, Demeter was the goddess of grain and the harvest, Poseidon ruled over the seas, Athena was the goddess of wisdom, etc. It is perhaps not surprising, therefore, that in the fourth century BCE, when a young and dashing Alexander the Great conquered all of the territory from Greece to India and bestowed the gifts of Greek culture and civilization on the barbarian regions under his armies' control, in the popular mind he became associated with the youthful version of Dionysus--the god who was also believed to have traveled from Greece to India spreading the fruits of cultivation and civilization.

Centuries later, when Augustus came to power, he claimed the special protection of Apollo. As previously noted, one reason may be that, according to Homer's Iliad, Apollo had come to the aid of the Trojans, whom the Roman claimed as ancestors. Equally important from Augustus's perspective, however, was the belief that Apollo was also the god of the sun's light and of prophecy. Accordingly, the poets of the Augustan era depicted Apollo as one of the heralds of the return of the Golden Age of human prosperity and happiness. Frequently by inference and occasionally by acclamation, Augustus himself was celebrated by these same poets as the divinely designated agent of the prophecy's fulfillment.

The Emperor as the Symbolic Presence of Zeus/Jupiter on Earth: Even more relevant to the rival message of the Christian gospels, however, was the gradual development of the relationship between the emperor and Zeus (Jupiter) himself, the sovereign ruler of the gods and the world. During Augustus's reign, a number of large imperial cameos were carved on semi-precious stones and distributed as gifts among the emperor's inner circle.