The Complexity of His Religious Identity

Jesus was viewed as healer, moral teacher, apocalyptic preacher and, ultimately, the Messiah. Samuel Ungerleider Professor of Judaic Studies and Professor of Religious Studies Brown UniversityJESUS AS HOLY MAN

What did it mean to be a holy man in first century Palestine?

What did it mean to be a holy man in first century Palestine?

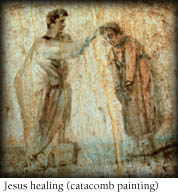

There is a complex variety of historical traditions about Jesus. He appears in our records, primarily the gospels, in different guises, doing different kinds of things. If you have to ask Jesus to fill out the passport application, or something, where he has say, ten or twelve spaces and he must fill in a single noun and say what is he.... what could you write? Well, there are a wide range of possibilities, but I think they all come down in the final analysis to a single one which is he's a holy man. That is to say, a person who was believed by his followers, by his disciples, by eye witnesses, to somehow be diffused with a divine presence.... He is able to do things that the rest of us can't do. He sees things that the rest of us don't see. He hears things the rest of us don't hear. He is a human, of course, but somehow he is possessed by a god, or the God, or a divine spirit or an angel or something that somehow has elevated him above the ordinary, so that he is able to do things the rest of us simply can't do. This is a recognized social type, both in the history of Judaism, and in fact, virtually all the world's religions, all the world's societies and cultures who have different names for such people. And even in the Hebrew Bible we can recognize this type in the Elijah type from the Book of Kings, they are characterized by their ability to do miracles. In Jesus' case, especially healings, which seems to have been something of a specialty of his, for which he had a great reputation. People would bring from miles around, judging from the gospel, they would bring their, the sick, the frail, to Jesus to be healed, as if somehow just a touch from the holy man would suffice to effect a cure, just looking at the Holy Man might suffice to effect a cure....

There is a complex variety of historical traditions about Jesus. He appears in our records, primarily the gospels, in different guises, doing different kinds of things. If you have to ask Jesus to fill out the passport application, or something, where he has say, ten or twelve spaces and he must fill in a single noun and say what is he.... what could you write? Well, there are a wide range of possibilities, but I think they all come down in the final analysis to a single one which is he's a holy man. That is to say, a person who was believed by his followers, by his disciples, by eye witnesses, to somehow be diffused with a divine presence.... He is able to do things that the rest of us can't do. He sees things that the rest of us don't see. He hears things the rest of us don't hear. He is a human, of course, but somehow he is possessed by a god, or the God, or a divine spirit or an angel or something that somehow has elevated him above the ordinary, so that he is able to do things the rest of us simply can't do. This is a recognized social type, both in the history of Judaism, and in fact, virtually all the world's religions, all the world's societies and cultures who have different names for such people. And even in the Hebrew Bible we can recognize this type in the Elijah type from the Book of Kings, they are characterized by their ability to do miracles. In Jesus' case, especially healings, which seems to have been something of a specialty of his, for which he had a great reputation. People would bring from miles around, judging from the gospel, they would bring their, the sick, the frail, to Jesus to be healed, as if somehow just a touch from the holy man would suffice to effect a cure, just looking at the Holy Man might suffice to effect a cure....

If you believed in him, of course, he was a man possessed by God. If you did not believe in him you would say he was a magician, a charlatan, a faker, a pretender, just a cheap trickster, nobody of any consequence. So the same acts might be construed differently depending on where you're coming from, what your perspective was. This would be the core then of what Jesus was, I think.

The Lillian Claus Professor of New Testament Yale Divinity SchoolCYNIC OR APOCALYPTIC PREACHER?

And how would you describe Jesus as a preacher?

Jesus was a very creative and engaging preacher, we know that. And contemporary scholars have tried to find analogies between his preaching and the images he uses, the parables he uses, the prophecies that are attributed to him... between those materials and contemporary preachers of various sorts. In recent years, it's become quite popular among some scholars to think of Jesus as a cynic. By a cynic I mean someone who was a member of a kind of countercultural movement; the hippies of the Hellenistic world were the cynics. They were very critical of conventional religion, conventional philosophy, conventional behavior. And they issued to the Hellenistic world generally a call to return to nature, to a natural and a simple way of life. There were some things in the preaching of Jesus that are analogous to that kind of call. "Consider the lilies of the field," for instance, is something that is very reminiscent of some cynic preaching.

However, there's something that I think differentiates Jesus from most cynics who seem to have been by and large very individualistic. Jesus does seem to have had a concern for the reign of God as something that effects the people as a whole.... And I take seriously the claim that he called people together in some sort of fellowship, and probably used symbols that in some way relate to the tradition of the people of Israel. That he was, in effect, constituting a call [for the] reform of the people in Israel, and that seems to be a very uncynic kind of thing. So those elements in his teaching and his proclamation that have to do with the reign of God and the people bring him closer to what we might describe as an apocalyptic preacher or someone who was concerned for God's intervention into human history to set Israel right. So, bottom line, Jesus was a very complex kind of character, and to put him in one or another of these pigeon holes, I think, is a mistake, and doesn't do justice with to the complexity of the evidence that's available....

If we take the Gospel of Mark, Chapter 13, we find a series of predictions about the end of the world. The skies will be darkened, the stars will fall from heaven, there will be earthquakes, trials and tribulations, war, and rumors of war. And then at the end of that period, a divine figure, the Son of Man, will come, will enter into human history and will inaugurate God's kingdom. That whole series of predictions is an example of apocalyptic prophesy. A prophesy of God's intervention into human history at the end of time to bring to realization all of the things that God has promised to his people. That's more or less what we mean by apocalyptic eschatology. If we take the attribution of that series of prophesies to Jesus seriously, then we'd have to classify him as an eschatological prophet.

There is, however, reason to believe that some of those prophetic statements attributed to Jesus probably were creations of the early church and put on his lips in order to help his followers to understand their relationship to their own history and to the catastrophes that were developing during the course of the first century. If we look at some of the other elements in the teaching of Jesus, there seems to be a critical stance towards some of these prophetic elements. So for instance, there are sayings where Jesus says that he does not know when the end will come. And if we look at the way in which he uses some symbols that are connected with these hopes for eschatological intervention then we seem to see Jesus using them in odd ways. Ways that suggest he may have been critical of some of those eschatological hopes.

So it's my understanding that Jesus probably grew up in an environment where some people nurtured these hopes for divine intervention into human history, that he may have shared them at some point in his life, if indeed he was a disciple of John the Baptist and was baptized by him. And if John the Baptist was such an apocalyptic preacher, it's entirely reasonable to presume that Jesus had some connection with those eschatological hopes. But the way in which he worked them out and the way in which he came to understand the reign of God or the kingdom of God suggests that he didn't buy in totally to that eschatological vision that then gets reworked by his followers into such passages as Mark 13.

William Goodwin Aurelio Professor of the Appreciation of Scripture, Boston UniversityHEALER, TEACHER, PREACHER

One of the most interesting and frustrating aspects of the stories about Jesus in the gospel is that they speak about him in so many different ways. There are elements of Jesus' public career, if you want to look at it that way, where he seems like a healer.... [I]n Mark, he's first of all an exorcist, somebody who drives out demons and drives out sickness. He is depicted as a religious teacher in the Gospel of Matthew. The Beatitudes, [the] Sermon on the Mount, are part of that teaching. He's constantly having arguments about what the correct way to live Jewishly is....

He's depicted also as somebody who's talking about the coming Kingdom of God. If all we had were the gospels, if that were all we knew about this moment in the development of Christianity as a religion, we might think that the attribution of apocalyptic hope to Jesus came from a level after his lifetime, or maybe was the editorial decision of the evangelist, who, after all, is writing sometime between 70 and 100. And Jesus dies around the year 30. So there's that gap. In other words, we could look at these apocalyptic elements and see them as a kind of literary theme, but not telling us anything about Jesus.

I think, though, that [it's important to look at] Paul's letters that are written 15 years earlier than the first gospel, by a person who doesn't know Jesus, but by a person who is in a movement that is creating itself around the name and the memory of this man, Jesus. And... Paul himself is also talking about the coming Kingdom of God with a different improvised wrinkle to it: that the son of God, namely Jesus, is going to come back ...and now the Kingdom is also going to arrive. I want to put Paul between the Jesus of history and the different Jesuses that stand in the gospels, and line up what's in the gospels with what's in Paul.... [Paul is] talking about a coming Kingdom of God. He's talking about the transformation of the living and the resurrection of the dead. He's talking about a spirit of holiness transfusing Christian communities. He's talking about Jesus coming back. He's talking about God intervening definitively in history. He's talking about the end of evil. And either he, and the movement he stands in mid-century, are inventing this out of whole cloth, and it has nothing to do with the person they consider their founder and teacher had said, or Jesus himself had also said something like that. I think it's less elaborate to think of Jesus, Paul, and the early church as on this kind of continuum.

Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies DePaul UniversityWHO DID JESUS THINK HE WAS?

Based on what evidence is left to us, who did Jesus think he was?

Jesus talks quite clearly about the Kingdom of God, and there's no hesitation about it. And that means this is the will of God. Jesus is making statements about what God wants for the earth. And there is no "The word of the Lord came to me," or there's no "I've thought about this." It seems self-evident. I think that's exactly what it is for Jesus. The Kingdom of God is radically subversive of the Kingdom of Caesar, and that's self-evident to Jesus because he's grown up, as it were, at the bottom of the heap and he knows the heap is unjust. It's so obvious for him, it is beyond revelation.... It's coming straight out of the Jewish tradition that this system is not right. Now, his followers are going to ask him, of course, a very obvious question, "Who are you?" And I find no problems that during the life of Jesus, certain of his followers could have said, "He is divine." And by divine, meaning, "This is where we see God at work. This is the way we see God" or, "He is the Messiah." But then, they'll have to interpret the Messiah in the light of what Jesus is doing. He doesn't seem to be a militant Messiah, or maybe we would like him to be a militant Messiah. All of those options could have been there during the life of Jesus. I have no evidence whatsoever that Jesus was in the least bit concerned with accepting any of them, or even discussing any of them. He was the one who announced the Kingdom of God.

But did he think he was speaking for God?

Jesus had to think he was speaking for God, yes.

But did he think he had a special relationship with God?

I do not think that Jesus thought he had any special relationship with God that wasn't there for anyone else who would look at the world and see that this is not right. It was to Jesus so obvious that anyone should be able to see it. Now, on the other hand, most people weren't able to see that in the first century or the twentieth. So in that sense, yes, it is a unique relationship. And it's that on which later theology would build, of course.

It seems to me the implication of what you're saying is, approximately, that he's not God.

If somebody says, "This is the will of God," then I'm going to say, "Well, when I hear you , I'm hearing God then?" "Yep." "Well, then, you're kind of like God?" "Yep." "But, when you die, God doesn't die?" So, I mean, it's perfectly valid for somebody to say then, "Jesus is God." But they're going to have to explain what that means. And that means for me, that Jesus speaks for God. That what Jesus says is what God wants for the world.