|

|  |  |

Lawrence Weschler is the author of Mr. Wilson's Cabinet of Wonder

(1995). He is at work on a book titled "Vermeer in Bosnia," about the aftermath of the recent wars in the former Yugoslavia.

Article printed here with permission of the author.

|  |  |  |

During my first few months covering the ongoing Yugoslav war-crimes tribunal in

The Hague, faced day after day with the appalling sorts of testimony that have

become that court's standard fare, I took to repairing as often as possible to

the nearby Mauritshuis, so as to commune with the museum's three Vermeers.

"Diana and Her Companions,"the "Girl With a Pearl Earring," the "View of Delft:

" astonishing, their capacity to lavish such a centered serenity upon any who

come into their purview.

More recently, however, I've increasingly found myself being drawn toward the

next room over, the one that houses Rembrandt's "The Anatomy Lesson of Dr.

Nicholaes Tulp," a work from the generation immediately prior to Vermeer's. It

was painted in 1632, the very year of Vermeer's birth (the year, for that

matter, of John Locke's birth, and Spinoza's as well), when Rembrandt, newly arrived in

Amsterdam, was only twenty-six years old. With this astonishing work he was

brashly hanging out his shingle as an accomplished

portraitist. The year 1632 was just about the midpoint of the Thirty Years'

War, an incredibly vicious religious struggle that savaged Northern Europe with

carnage every bit as harrowing as anything being described nowadays at the

tribunal -- mayhem that regularly slashed into the Netherlands, until the

conflict was finally brought to a (provisional) end with the Treaty of

Westphalia, in 1648.

The war had provided the occasion for the publication,

in 1625, of the seminal work by an earlier son of Vermeer's Delft, Hugo

Grotius: "On the Law of War and Peace,"

a text often considered to be the foundation of all modern international law,

in particular of the Hague tribunals. The war's dark imperatives can likewise

be seen impinging on Rembrandt's great painting.

"The Anatomy Lesson" is so famously overexposed, so crusted over with

conventional regard, as to be almost impossible to see afresh. And indeed,

when I recently came upon the painting once

again, rather than seeing it I found myself recalling an essay I hadn't

thought about in almost thirty years -- the English critic John Berger's 1967

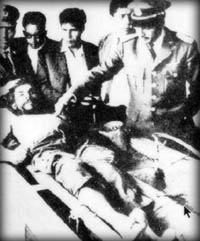

rumination on the occasion of Che Guevara's death. Responding to the

simultaneous appearance seemingly all over the world of that ghastly photo of

Che's felled body, stretched out half naked across a bare surface and surrounded by the proud Bolivian

officers and soldiers who had succeeded in bagging the revolutionary leader,

Berger made a startling connection to Rembrandt's "Anatomy Lesson." Gee, I

remember thinking at the time, this man doesn't look at his morning paper the way I look at mine.

But surely he was right. One could even say that Rembrandt's was the image,

almost hard-wired into the photographer's mind and the soldiers' very bodies,

that had taught them all where to stand in relation to one another and to the grim

object of their smug display.

Yet now, standing before the painting itself, I realized that for all my

conventional acquaintance with its image, I'd never seen it correctly -- or,

anyway, my memory was wrong in one crucial respect. The professor is poised in

mid-lecture beside a cadaver, its left forearm splayed open to reveal all the

sinewy musculature just beneath the skin. There is a mountain of onlookers:

some gaze out strangely toward us while the rest-and this is the part I

remembered most vividly-lean forward, gawking (like us) at all that gore. (Come

to think of it, maybe the ones gazing toward us are staring precisely at our

own queasiness in the face of such morbidity.) Yet now, standing before the painting itself, I realized that for all my

conventional acquaintance with its image, I'd never seen it correctly -- or,

anyway, my memory was wrong in one crucial respect. The professor is poised in

mid-lecture beside a cadaver, its left forearm splayed open to reveal all the

sinewy musculature just beneath the skin. There is a mountain of onlookers:

some gaze out strangely toward us while the rest-and this is the part I

remembered most vividly-lean forward, gawking (like us) at all that gore. (Come

to think of it, maybe the ones gazing toward us are staring precisely at our

own queasiness in the face of such morbidity.)

Only, as I now could plainly see, that's not what's actually happening in

Rembrandt's canvas. Of course, the theme of mortality and morbidity is there --

rendered all the more unsettling by the conspicuous resemblance between the

cadaver's face and those of many of the onlookers. But that's not what the onlookers are focusing

on; death (their own or anybody else's) hardly seems to be on their minds at

all. On the contrary, the innermost trio is gazing at the professor's

living hand, the one with which he has been demonstrating the grips and

gestures made possible by this, and this, and this other newly exposed muscle

or tendon.

According to most traditional academic iconographic readings of the painting,

the trio is not looking at the professor's hand but rather gazing right past

it, at the opened book beyond, in the painting's lower right-hand corner -- a

thick anatomical tome, supposedly representative in this context of

authoritative education and the passing down of specialized knowledge. Nonsense

-- though, admittedly, a peculiarly self-referential art-academic,

specialized-tome-generating sort of nonsense. Just look at the picture. They're

looking at the professor's hand, and, indeed, they're looking at it

wonderstruck, spellbound, as if they've never before seen anything like it.

For what a marvel of motility it is -- with its capacity for compression and

extension, for flex and repose, grip and rotation. The hand in itself is a

veritable miracle. One is momentarily reminded by the living hand hovering over

the recumbent, lifeless body of that other great painterly trope of creative

dexterity: God's own hand extended toward the recumbent Adam's, in

Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel (an image that was surely known to Rembrandt from

the countless etchings then circulating throughout the Netherlands). More to

the point, a flexing hand -- the focus of all this awed attention-is a

painter's own foremost implement, the one with which he wields his brush. You

can just seeRembrandt painting the picture, his own actual hand burnishing the

professor's painted one as the painted class gazes on in hushed astonishment. This is a

painting, then, about looking at hands, about vision and malleability -- about

the fundamentals of painting itself.

Or, more generally, about living. It's not, as we are sometimes given to

recalling, a morbid dwelling upon death but rather a celebration, a defiant

affirmation of life and liveliness and vitality generated, as it happens, at a

moment when the world was choking with death and dying.

All of which brought me back to the tribunal, and to those hours I'd been

spending hunched in the visitors' gallery, taking in the endless tales of

horror and grisly death. I thought about the judges and the lawyers, the

investigators and the forensic anthropologists. I remembered, for instance,

Gilles Peress's remarkable photograph of the forensic anthropologist William

Haglund ever so carefully extracting a decaying body from a mass grave on a farm outside Srebrenica

(another image of Death and the Professor) -- the tender, almost loving way he

reaches to cradle and recover the rotting corpse. Almost a Pieta image.

And I realized how, appearances to the contrary, all these labors aren't about

death at all but rather about life and the living. They are about the living

witness owed to every one of the once-living victims. "In these matters," the

Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert (writing in the shadow of his own country's

genocide-saturated history) insisted, "we must not be wrong / even by a single one / we are despite everything / the guardians of our brothers." They are

about securing the possibility of an ongoing life for the survivors (the widows

of Srebrenica, for instance, still stranded in limbo, straining for justice, or

at least for confirmation of the fate of their loved ones). They are about

healing a community once ravaged by war, so that liveliness can come flowing

back over an otherwise blighted terrain. They are about the lives of

generations yet to come, about breaking that cycle of atrocity followed by

impunity which plays such a large role in provoking atrocious communal retribution decades

down the line. And, finally, they are about restoring the equilibrium of the

living world itself, the world we all share. For, as Herbert concluded in his

history-laden poem, "ignorance about those who have disappeared /undermines the

reality of the world." It's a lesson that Rembrandt, too, was busy teaching.

|  |