|

Almost fifty years ago, in 1950 and 1951, a Special Committee of the U.S.

Senate held nationally televised hearings on a subject never before given such

a significant public forum: the Mafia and organized crime. The Committee,

chaired by Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee, introduced average Americans to

men like Lucky Luciano, Vito Genovese, and Meyer Lansky, and detailed their

business -- gambling, corrupt infiltration of legitimate business, and

violence. The Committee's final report famously concluded: "There is a

Nation-wide crime syndicate known as the Mafia, whose tentacles are found in

many large cities. . . Its leaders are usually found in control of the most

lucrative rackets in their cities. . . There are indications of a centralized

direction and control of these rackets. . . The domination of the Mafia is

based fundamentally on 'muscle' and 'murder.'"

Almost fifty years ago, in 1950 and 1951, a Special Committee of the U.S.

Senate held nationally televised hearings on a subject never before given such

a significant public forum: the Mafia and organized crime. The Committee,

chaired by Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee, introduced average Americans to

men like Lucky Luciano, Vito Genovese, and Meyer Lansky, and detailed their

business -- gambling, corrupt infiltration of legitimate business, and

violence. The Committee's final report famously concluded: "There is a

Nation-wide crime syndicate known as the Mafia, whose tentacles are found in

many large cities. . . Its leaders are usually found in control of the most

lucrative rackets in their cities. . . There are indications of a centralized

direction and control of these rackets. . . The domination of the Mafia is

based fundamentally on 'muscle' and 'murder.'"

In the decades since the Kefauver report we have learned more about the Mafia

in America -- some have said that Italian mobsters' popular celebrity in books,

movies, and television has grown while their actual power as a criminal

syndicate has waned. At the same time, we also have frequently heard of the

"changing face" of organized crime in America, with new groups challenging La

Cosa Nostra for criminal dominance of illegal markets: Chinese Triads and

Tongs, Jamaican Posses, Colombian Drug Cartels, Vietnamese Gangs. Beginning in

the late 1980's, a new group was added to the list -- the Russian Mafia --

centered in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, the largest Soviet/Russian emigre

community in the United States.

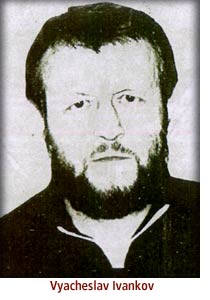

The questions that U.S. law enforcement and criminologists began to ask of the

Russian Mafia in the mid-1990's recalled the earlier questions of the Kefauver

Committee with respect to La Cosa Nostra: Is there a Russian mafia in America?

If so, is it centrally organized and directed? How deeply has it penetrated

legal and illegal markets? Answers are not easy to come by, but no response

could be complete without considering the biggest Russian crime figure to be

caught and tried in the United States: Vyacheslav Ivankov or, as he was

nicknamed, Yaponchik ("Little Japanese") -- the same man whose connection to

hockey star Slava Fetisov raised concerns for the NHL.

Was Ivankov sent to America by Russian organized crime leaders to run all North

American operations? This was the view put forward by the FBI and reported

widely by the press, but what was it based on? One reporter, Scott Anderson,

writing in Harper's Magazine in December, 1995, went to Brighton Beach

in search of Ivankov and came away a skeptic. Anderson concluded:

"Ivankov was a mafia godfather because it served everyone's interest that he be

one. It gave the media a frame, a way to personalize stories about a complex

issue. It gave the FBI a symbol to take down, a tool with which to convince

the Russian emigré community that justice would prevail. . . And not

least of all, it gave Ivankov the necessary status and cachet to be called upon

as muscle [in extortion and protection rackets] in the first place." ("Looking

For Mr. Yaponchik," p. 51)

Who was Ivankov? In this excerpt from Russian Mafia in America

(Northeastern University Press, 1998), James O. Finckenauer, a Professor of

Criminal Justice at Rutgers University, and an expert on Russian organized

crime, reviews all the evidence on Ivankov and offers this authoritative

assessment.

home |

interviews |

russian mob in north america |

details expose |

ivankov: taking a closer look |

video excerpt |

join the discussion

glossary |

links |

who's who |

tapes & transcripts |

synopsis |

press

FRONTLINE |

pbs online |

wgbh

New Content Copyright © 1999 PBS Online and WGBH/FRONTLINE

| |