The strategy of combating drug abuse through treatment has been controversial

throughout the thirty-year history of America's war against drugs. Prior to

President Nixon's creation of the Special Action Office for Drug Abuse

Prevention (SAODAP) very little federal money was spent on treatment.(see the chart) Drug

users were stigmatized--addiction was seen as a weakness, and addicts were

believed to be self-centered and hedonistic. This perception began to change

throughout the 1970s and early 1980s. Vietnam vets returned home addicted to

heroin, and use of marijuana among the middle and upper classes began to

increase, which prompted more serious attention from the Administration.

Two-thirds of Nixon's federal drug budget was set aside for treatment and

prevention.

The crack epidemic of the mid-1980s and its resulting crime wave led to a

restigmatization of addicts. Drug Czar William Bennett's strategy was to

"denormalize" drug use, which had become more socially acceptable during the

1970s. He preached that users should be held accountable for their behavior.

Allocation of public funds for treatment dwindled, while law enforcement

budgets skyrocketed.(see the chart)

Over the past decade, there has been a debate over the fundamental nature of

addiction, which has resulted in very different models for effective treatment

programs. A growing number of doctors have embraced the "disease model" of

addiction, and many researchers now support treatment as a sound investment of

public funds. Both private and federally funded studies have found that

treatment is not only rehabilitative, but it is a cost-effective way to combat

drug abuse. Yet there is a significant treatment gap in the United States--the

number of people seeking treatment far outnumbers the available programs.

According to the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), half of the

3.6 million people who need treatment in the U.S. cannot find or afford it.

In 1935, Alcoholics Anonymous was the first treatment organization to label

addiction a disease. Based on the ideas of researcher E. M. Jellinek, those who

subscribe to the 12-step theory of recovery believe that certain individuals

are physiologically incapable of using drugs or alcohol in moderation.

Currently, many treatment programs are based on the disease model of addiction.

This idea is also gaining currency among policy makers, such as Barry R.

McCaffrey, director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP).

According to McCaffrey, drug abuse "...is indeed treatable, [and]...the

[treatment] techniques are more responsive in terms of statistics than

currently available cancer treatment..."

Dr. Alan I. Leshner is the director of the National Institute on Drug

Abuse (NIDA). He claims that the brain of a drug addict is chemically

different from that of a non-addict, and that the addict should be

treated accordingly. "We wouldn't ask for a simple solution to another brain

disease," he says. "We invest in long-term rehabilitation for stroke victims

and schizophrenia." According to Dr. Leshner, when a person first begins to

use a drug such as heroin or cocaine, there is a slight chemical alteration to

the brain. After a prolonged period of regular drug use, there is a more

significant chemical change in the brain and drug use is no longer voluntary.

At this point a "user" becomes an "addict." Dr. Leshner believes the changes to

the brain incurred by heavy drug use do not disappear when an addict stops

using, and this results in the frequency of relapse among addicts.

Dr. Herbert D. Kleber is the medical director of the National Center on

Addiction and Substance Abuse in New York, and a Professor of Psychiatry at

Columbia University. Like Dr. Leshner, Dr. Kleber supports the view that

addiction is rooted in biology. Dr. Kleber believes strongly in the

effectiveness of treatment, and under his directorship, a $3 million assessment

of treatment centers across the U.S. is currently under way. However Dr.

Kleber does not believe that biology is the sole factor influencing drug abuse

tendencies. "If you are the son of an alcoholic, you have a four times greater

chance of becoming an alcoholic than someone who doesn't have that history,"

Kleber says. "But it's not destiny, it's a risk factor. And there are other

risk factors...I would say that drug addiction is a

bio-psycho-social-phenomenon. So medication for drug abuse must always be given

in an appropriate social context, with the appropriate therapy."

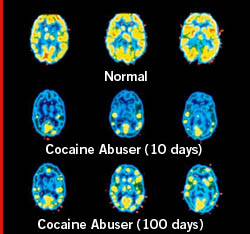

As technology has improved, the brain scan has become one of the most important

tools of the disease model of addiction. Doctors are now able to compare the

neurological changes in addicts to the normal functions of a non-addicted

individual.

|  |  |

PET scans of normal brain and brain of cocaine user.

Courtesy of Brookhaven National Laboratory

|  |  |

This slide shows images of a healthy brain (top row) and the brain of a cocaine

addict taken at 10 days (middle row) and 100 days (bottom row) after the last

cocaine dose. Working from scans like these, taken at the Brookhaven National

Laboratory, on Long Island, New York, Dr. Nora D. Volkow studies the long-term

effect of cocaine use on the brain. Even 100 days after a cocaine addict has

stopped using drugs, the decreased metabolism in the brain's frontal area

remains visible. This region of the brain influences behavior such as

regulating impulsive and repetitive behavior, planning and organizing

activities, and critical thinking.

Many of those who believe in the disease model of addiction medicate addicts

during treatment. However there is no miraculous medical solution to addiction.

While cocaine and heroin abuse can be medically treated, there are drawbacks to

each, and medications for marijuana and methamphetamine addiction do not exist.

Cocaine addiction:

Amantadine is a drug that has been used to alleviate the withdrawal symptoms of

cocaine. It increases dopamine activity in the brain, mimicking cocaine's

"high", though the feeling of pleasure (the "buzz") is much less acute. The

side effects of amantadine include the purplish swelling of ankles,

restlessness, depression, and congestive heart failure.

Because the cocaine high is linked to an over-production of dopamine, in

theory, "dopamine blockers" should prevent the cocaine from taking effect.

However "dopamine blockers" are not recommended because they severely affect

normal feelings of pleasure. Other side effects include lack of motivation,

joylessness, drooling, and jerky movements.

A great deal of research has gone into finding a vaccine for cocaine.

Researchers hope that a vaccine would cause antibodies to break down the

cocaine before it gets to the brain and thus prevent a high. However, because

cocaine addicts may have weak immune systems, the presence of vaccine-induced

antibodies may trigger health problems. Also, if an addict is determined to

take cocaine despite having had a "vaccination," overdose becomes more

likely.

Opiate addiction:

Naltrexone is a drug which blocks the receptors involved with the heroin

"high." Therefore, with regular use of naltrexone a heroin user will no longer

be able to achieve a high. Although naltrexone is non-addictive and has no

potential for abuse, many heroin addicts find naltrexone unpleasant. Doctors

often have to prescribe anti-depressants to counter these side effects.

Therefore natrexone is not very commonly used.

Methadone is the most successful drug used to treat heroin addiction.

Methadone has a similar effect to heroin on the brain, but the effect lasts

much longer. The methadone high is far less pronounced than heroin, so it

stabilizes addiction. However critics of methadone say it is merely a

substitute addiction for heroin.

One of the most promising new drugs on the treatment horizon is buprenorphine.

Buprenorphine has the calming effect of methadone, but it blocks the high of

heroin in a way similar to naltrexone. Since it has a long-lasting effect,

buprenorphine need only be administered once a day. The FDA has not yet made

this drug clinically available.

There is a wide variety of treatment centers which base their practices on the

disease model of addiction, including 12-step recovery programs such as

Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous (NA), Chemically Dependent Anonymous

(CA), and Marijuana Anonymous (MA).

Another fairly common form of treatment is the "Minnesota Model" pioneered by

centers like the Betty Ford Clinic and Hazelden. These facilities require an

inpatient stay, usually between 10-28 days. Treatment is usually based upon

Narcotics Anonymous, group support, and detoxification away from the drug-using

environment.

Halfway houses are treatment programs similar to the "Minnesota Model,"

although they are much less expensive. Halfway house residents work during the

day in order to pay for their care. Treatment usually takes place during the

evening, and is less intensive than full-time inpatient care.

The "Oxford House" system consists of group residences for those who subscribe

to the 12-step recovery program. Treatment is less intensive than in a halfway

house or inpatient facility. The residents of an Oxford House try to encourage

each other to stay clean and sober.

The characterization of addiction as a purely biological and physical disease

is controversial. Many doctors and researchers believe that although regular

drug abuse may induce compulsive behavior, drug addicts always retain a degree

of control over their behavior. They argue that a drug never entirely subsumes

an individual's decision-making capability and point to cigarette smokers to

reinforce this argument. Many smokers may be addicted to nicotine but are able

to quit if they have a strong enough desire.

Dr. Gene M. Heyman is a research psychologist at McLean Hospital, Boston, and a

lecturer at the Harvard Medical School. He believes that chemical alterations

in the brain caused by drug addiction are not infallible proof of the disease

model of addiction. He explains that when someone is hungry, the sight of food

will affect a chemical change in the brain. Heyman has said, "When someone sees

a McDonald's hamburger, things are going on in the brain, too, but that doesn't

tell you whether their behavior is involuntary or not."

There are programs that embrace the idea of addiction as a behavioral trait

that can be overcome using the strength of personal choice. One example is the

Rational Recovery (RR) program. RR believes that self-empowerment

through abstinence is the crucial component of recovery, and 12-step groups are

counterproductive to successful recovery. RR encourages people to end their

addiction through "addictive voice recognition training" (AVRT).

Secular Organizations for Sobriety (SOS) is a treatment for those uncomfortable

with the spiritual aspect of 12-step programs. Founded by an alcoholic named

James Christopher, SOS believes an individual is responsible for maintaining

his or her sobriety, although peer support may be useful to achieving that end.

In 1987, SOS was recognized by the California court system as a valid

alternative to AA.

Another program driven by the notion of volition as the key component of

recovery, is Self Management and Recovery Training (SMART). This program

focuses on enhancing individual motivation and encourages addicts to learn new

behaviors. Like RR and SOS, SMART does not invoke the religious aspect of

12-step programs.

An increasing number of experts are beginning to view drug addiction as a

phenomenon that has its roots in social dysfunction. This "root causes" school

of thought believes that in order to treat addiction, one must address the

reasons behind the addiction. Proponents of this belief point to the fact that

many hard-core addicts come from low income, low-opportunity backgrounds.

Subsequently, those who emphasize the "root causes" approach call for a

percentage of drug funding to be spent on education and employment in

low-income areas. They believe drug abuse cannot be combated without addressing

social and economic inequalities.

Elliot Currie, Criminologist at the Center for the Study of Law and Society at

the University of California at Berkeley, believes treatment must be linked to

the addict's broader lifestyle improvement. In an article entitled "Yes,

Treatment, But..." published in the "Beyond Legalization" issue of The

Nation Currie articulates how social improvements could be effected. He

writes, "We need a multilayered approach: we need better treatment, more

harm-reduction programs, selective decriminalization, more creative adolescent

prevention efforst and much more - all in the context of a broader 'strategy of

inclusion' that would systematically tackle the misery and hopelessness that,

as study after study shows, has bred the worst drug abuse..."

home ·

drug warriors ·

$400bn business ·

buyers ·

symposium ·

special reports

npr reports ·

interviews ·

discussion ·

archive ·

video ·

quizzes ·

charts ·

timeline

synopsis ·

teacher's guide ·

tapes & transcripts ·

press ·

credits ·

FRONTLINE ·

pbs online ·

wgbh

web site copyright WGBH educational foundation.

|