Clinton turned to consultant Dick

Morris to fashion a comeback following the Democrats' devastating loss to the

Republicans in the 1994 Congressional election. Morris, who had helped Clinton

develop political strategy since his race for governor of Arkansas in 1978,

aimed to help the president move more to the center politically. Clinton,

fearing resistance from his staff, initially kept Morris's assistance a secret.

At what point do you get taken into Clinton's confidence, in terms of

what's happening politically in the fall of '94?

Morris: Well, in the early days of October '94, he called me and he

said, "What do you think I should do about the congressional elections?" And I

said, "Well, let me take a poll, and give you some advice." Because that's how

I usually do it.

So I took a survey with him. And I remember we were preparing the

questionnaire, and he's on the phone with me. I figured that the President of

the United States wouldn't have much time to fool with the questionnaire. No,

he spent an hour and a half on the phone with me, going over each word of each

question: "Make sure you ask about this accomplishment," "Make sure you ask

about that accomplishment," "No, no, you have here that I created three million

jobs; it's really three and a half million jobs." And he's all over that. So

I did the poll, and I found something very interesting. I found that nobody

believed in the big achievements of his -- nobody believed that he was reducing

the deficit; nobody believed he was reducing crime; nobody believed he was

creating jobs; nobody believed he was lowering unemployment.

But they did believe the small achievements. They believed he'd lowered the

student loan interest rate; they believed that he had succeeded in the Family

and Medical Leave Law; that he'd made good appointments to the Supreme Court;

that he'd expanded and saved the school lunch program. The small

achievements.

So I had a conference call with him and Hillary. And I said, "Stop trying to

sell the big achievements. Sell the small ones. They'll believe those, and

that's enough to move votes in your direction." And he kept saying, "No, but

if I tell them all the jobs I've created, I tell them all the stuff I've done

-- " And I said, "Stop trying to get elected for the right reasons. Just try

to get elected." And then Hillary joined in the chorus and said, "Bill, all

you're doing is just trying to give them the big achievements. You're trying

to justify yourself to history. Focus on the election. Focus on these

voters."

And then, he didn't follow the advice. And he called me a week before the

election, and he said, "How do you think it's going to come out?" And I said,

"You're going to lose the House and the Senate." And he said, "The House and

the Senate? The Senate I can understand, but the House? No way I'm going to

lose the House." And I said, "Well, I think you'll lose the Senate by six

seats, and you'll lose the House by 20." He said, "Twenty seats in the House?

You're crazy." And I said, "Well, just in case what you say isn't going to

happen happens, can I send you a speech as to what to say at that point?" And

he said, "Okay." And then, the next thing, he was giving it, after he'd lost

both houses.

... But he wasn't sure that I would work out, and I wasn't sure that I would

work out, either. I didn't know if his staff would accept me. I didn't know

if he was really going to follow the advice I was giving him. For two years he

hadn't listened to a darn thing I'd said. I'd been advising against almost

everything he'd done for two years, and he hadn't listened to any of it. And I

wasn't going to go into a situation where he wasn't listening to me, I'd end my

career with the Republicans, and I would be ineffectual with him.

... But he wasn't sure that I would work out, and I wasn't sure that I would

work out, either. I didn't know if his staff would accept me. I didn't know

if he was really going to follow the advice I was giving him. For two years he

hadn't listened to a darn thing I'd said. I'd been advising against almost

everything he'd done for two years, and he hadn't listened to any of it. And I

wasn't going to go into a situation where he wasn't listening to me, I'd end my

career with the Republicans, and I would be ineffectual with him.

From his point of view, he had a liberal Democratic staff that disapproved of

everything I would urge. And he wasn't about to announce me with great fanfare

if I wasn't able to really make the grade and give him advice that was

effective. So both of us were sort of having a trial marriage. And we both

figured it was better for me to be involved secretly. So I made up a code

name, "Charlie" -- which, by the way, is the name of my favorite Republican

political consultant, Charlie Black. And I just thought it was kind of funny

that I'd use a Republican name, working for Clinton.

Panetta: I thought it was weird. I thought it was a strange, almost

love/hate relationship that had gone on, back in Arkansas and I had heard the

stories about the relationship then. And suddenly we started finding out that

we were getting poll results from Morris, operating -- and the code word I

think was "Charlie" that they started using for him because they didn't want

the world to know that Morris was involved.

But it was clear that the president had turned to him in the past when he was

in political trouble and felt that he needed to have that kind of help again

because he felt the world had crumbled on him. And he was intent on making

sure that whatever had to be done would be done to ensure that, not only would

he get reelected, but that every effort would be made to try to get the

Congress back.

McCurry: Very interesting because there was a sense -- long before

the president sort of introduced everyone to the idea that Dick Morris would be

a member of the strategic team -- it was clear that he was getting advice, that

he was taking to heart from some external source. And it was frustrating a

little bit in the days of the spring of 1995 to know that there was some other

group of advisors that were working or some kitchen cabinet or some process

that was not part of the defined process of the White House.

Stephanopoulos: Charlie. The first time I ever saw the word

"Charlie" was on a little yellow post-it note on the president's desk next to

his phone saying, "Charlie called." I thought, "Hmm, that's odd." And you

just sort of file it away. The first time I remember thinking that something

was going on, was in December of 1994. The president gave this Oval Office

address, which was supposed to be sort of his official response to the

Republican win and kind of set in the agenda for 1995. A lot of debate over

whether or not it was a good idea, but it was being given. And I remember, in

the drafting process, he and Hillary were sitting up in the residence all day

long, and then a lot of us were back in the White House working on various

drafts, working with the speechwriters. And one draft came back with this new

language in it. I think it was called the "economic bill of rights" or new

language that was labeling the new Clinton agenda, which was the old Clinton

agenda under the framework of a bill of rights. And I remember walking in with

the draft, and Hillary was there, and the president was there, and I said,

"Hey, where'd this language come from? It's pretty good." And Hillary just

smiled, and I thought sure that meant it was her. But it turns out that that

was Dick's first real major influence on a major address.

Panetta: I always had the feeling that the president wanted to listen

to the dark side, even though, you know, he clearly knew in his guts, I think,

where the issues were and what he wanted to do. He always wanted to listen to

the Morris voice to kind of say, you know, what are the thoughts of the most

kind of manipulative operation that could go on in politics? I want to hear

that voice. I want to hear what he's thinking.

Stephanopoulos: Over the course of the first nine months of 1995, no

single person had more power over the president, and therefore over the

government, than Dick Morris, no question about it.

Morris: And I said, "I don't understand why you take all my advice,

and you appoint a staff that hates me. And I think it's because you want me to

be like a little bird perched on your left shoulder, whispering into your ear

so nobody else can hear it, just giving you advice." And he had a big grin on

his face and he said, "You got it. Leave it with me. Just tell me what you

think I ought to be doing. Leave it with me. I'll take care of it. Don't

deal with my staff. If you need information, get it from them. If you need

facts, get it from them. But just give me the advice."

So during all of '95, I was trying to shoulder my way into staff meetings

and be included in this and that. And then in '96, I realized that I didn't

want to be included in anything. So I would refuse to go to any staff

meetings. Panetta used to beg me to come, and I would say, "No, I'm not."

Because in the last analysis, the channel that Clinton wanted me to pursue was

the direct, private channel that we had with each other.

Stephanopoulos: It's incredibly frustrating. It was incredibly

frustrating in the White House at that time to be living with a parallel black

hole White House that you couldn't fight openly, that you never knew when its

influence was going to be brought to bear, that you couldn't see. And you'd be

in a situation where, you know, the entire administration would be sent down a

path for a certain speech or a certain initiative, and then late at night it

gets upended in a phone call with Dick Morris, and it's just an incredibly

unproductive and just dispiriting way to work.

The Oklahoma City bombing provided Bill

Clinton with an opportunity to stand out as a leader. Just at a time when Newt

Gingrich and the Republican agenda dominated the political arena and Clinton

felt the need to reaffirm his relevance, he was able to bring the country

together as only a president could.

Backing up to 1995, there was a primetime press conference, April 18th, and

the president is asked about this sort of feeling in the press in Washington

that the Republicans seemed to be dominating the debate at this time. And the

president in this press conference says, "The president is still relevant

here."

Stephanopoulos: Channeling Dick Morris. Dick Morris was telling him to

buck up his confidence, "The president is still relevant, the president is

still relevant." Perfect example of the stage direction coming out of the

actor's mouth, as opposed to the script.

When that comment showed up on the front pages of all of the papers the next

day, what were you thinking?

Stephanopoulos: There wasn't a lot of time to think about it. I think

late the next morning the Oklahoma City bombing happened, and the president was

relevant.

Panetta: When the Oklahoma bombing came, his capacity to get out there

and, first of all, speak to the American people in a calm way and reassure

them, and ask them not to kind of prejudge what had happened here, and then

what he did following up on that, in terms of dealing with the victims and what

took place there, I think that, more than anything, brought out the human side

of Bill Clinton. And people really, for the first time in a long time,

connected with the president and what he was trying to be and who he was.

McCurry: Well, it was a defining moment in many ways because all

Americans needed a president to kind of come and help us understand this

horrible event. We needed someone that really would speak to our capacity to

get beyond the tragedy, our capacity to think through the realities of the kind

of world we live in now where something like this could happen. We needed a

president, quite frankly, to shut down some of the anti-Arab hysteria that

almost swept this country. Because remember, in the first several hours,

everyone was pointing fingers at Arab terrorists, which turned out to be

obviously wrong.

So, we needed a president. And I think by needing a president and by Bill

Clinton stepping in and filling that role more than adequately at that moment,

that was kind of a turn around moment for his presidency.

Emanuel: Early on, remember, people are criticizing him for being a

prime minister and not a president. Oklahoma is that moment in which he

emerges dogmatically and in his voice as a president. And I think the American

people can see him there. Reagan did it in the Challenger blow up. I think in

Oklahoma this president was a unifier. And it was a critical moment where we

were looking in at ourselves and we saw the enemy. And he was able to bring

out in a very dark moment of revenge, I think, the better angels of our spirit

as a country.

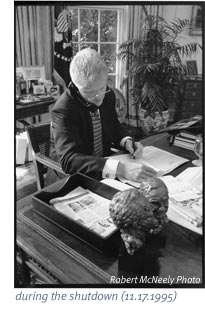

In a showdown over the budget in the

fall of 1995 the president did not compromise. After vetoing the budget

proposals sent to him by Republican Congressional leaders, the federal

government shut down twice. To many in the White House, it was the decisive

moment in his first term and helped him win reelection.

Going back to Morris, he is advocating certain things that are in the

polls. You're advocating other things. And here you have a Democratic

president really putting in a very Republican proposal.

Panetta: The debate by those of us who had worked on the economic plan,

gotten that passed, worked on the budget and got that put in place, was that

the president had clearly indicated that in his economic plan we would be able

to follow a certain path towards deficit reduction that ultimately would lead

to a balanced budget.

And our view was stick to what we put in place. You know, we got the economic

plan passed. It's having an impact in terms of deficit reduction. The economy

was beginning to become stronger and stronger. And so, the feeling was, rather

than just jumping to a political cliche of balancing the budget -- I mean, it's

what everybody says. Ronald Reagan said it at the time we were going to $300

billion deficits, that it had become almost meaningless in terms of the term

for the American people. Why run after that just because the Republicans were

kind of touting it again? The reality was to do it would involve some pretty

significant cuts in the Republican plan and it did.

So how do you counter that? Well the president felt that politically he could

not confront the Republicans without some kind of balanced budget plan to

respond to what they were proposing. So when he made that decision, the

economic team was willing to sit down and go through it and try to propose

something that at least made better sense than some of the things some of the

political people were talking about. And we went through that process and

ultimately we were able to have the president do it.

You said that before the president proposed his balanced budget, that there

was a lot of debate in the White House about that.

Rubin: Well, there was immensely strong commitment to continuing with

fiscal discipline. That debate no longer existed. But the question was what

is the best way to go forward? And there were those who felt that we should

continue on the fiscal discipline track that we were on, which would get us to

balance, but over some longer period of time. And there were others who felt

that it would make more sense, if we were going to continue on that track, to

put out a balanced budget proposal right now.

And the president was of the latter view, and he said that what we needed to do

-- and I can very specifically remember this happening in a meeting we had in

the Oval Office with him --was to put out a balanced budget proposal. Both to

best carry forward this whole strategy of fiscal discipline, and also to regain

the initiative, politically, more generally.

Morris: And I felt that in opposing the Republican budget cuts, we

had to make clear that they were not necessary to balance the budget. That you

could get rid of the deficit, as we in fact have done, and still preserve

Medicare, Medicaid, education, and the environment. That you could cut the

Post Office, or the Department of Labor, or minor programs, without really

getting into the stuff that people cared about.

And I told Clinton that I felt no amount of rhetoric will convince people of

that. You have to actually produce a balanced budget without cutting these

programs. And the staff was opposed to that. They were liberals who I think

for the most part really didn't want the deficit to go away. They were having

too good a time with the deficit. Because as long as there was a deficit, they

could run against the Republican cuts.

You develop a theory that comes to be known as "triangulation" after the

'94 elections. Very briefly, what was your thinking?

Morris: Well, we were locked into a very sterile conflict between the

left agenda and the right agenda. And it was like going into a restaurant and

not being able to order a la carte. If you wanted to have pro-choice, you had

to vote for the Democrats and accept high taxes. If you wanted to have

pro-life, you had to also accept government-less environment. There was a

coupling here on both sides that was inappropriate.

And I felt that what you should do is really take the best from each party's

agenda, and come to a solution somewhere above the positions of each party. So

from the left, take the idea that we need day care and food supplements for

people on welfare. From the right, take the idea that they have to work for a

living, and that there are time limits. But discard the nonsense of the left,

which is that there shouldn't be work requirements and the nonsense of the

right, which is you should punish single mothers. Get rid of the garbage of

each position that the people didn't believe in, take the best from each

position, and move up to a third way. And that became a triangle, which was

triangulation.

For those of your viewers who are into philosophy, it really is Hegelian in

concept: the idea of a thesis, an antithesis, and a synthesis. And when we

originally discussed it, we did so in terms of Hegel, which we had studied at

Oxford. But in American politics, we spoke of triangulation.

Stephanopoulos: Triangulation. Dick, whenever he was going to explain

to those of us who were slower than him on staff, he would say, "This is

triangulation," and hold up his fingers like this. And it was basically to

treat Democrats and Republicans in the House alike. Your adversaries were both

of them. The president is supposed to push off either one in equal measure and

appear to be above the political fray.

This was Dick Morris's idea.

Stephanopoulos: Yeah, and, you know, it's empty of substance. It's

amoral. But it makes some political sense at some level. And what the

president was so skillful at, as frustrating as it could be at times, was

taking parts of Dick's theory, parts of the triangulation theory, but not going

too far with it. And he got in more trouble when he accepted it whole.

Panetta: There were those of us on the staff who thought the president

would be willing to do whatever was necessary to cut a deal. And we kept

saying, "No. This is fundamental to everything that you have fought for. I

mean, you have set priorities for this country. You've said what you want for

education. You've said what you want for health care. You've said what you

want to do for the environment. And everything, they're putting into their

plan is against everything you're for."

But, nevertheless, inside of him, he always has this sense that "I know that

rational people ultimately can come together and cut this deal." So we had

made several offers, as the discussions went on. And the Republicans had

rejected them. They came back with some offers. We had rejected them. And

there was a moment -- in which the president -- we made another offer. And

Gingrich said, "I'm sorry. No. We can't accept it."

And the president looked at him and I think it's one of those moments when you

know that the president really got it. The president said to Gingrich, "I

simply can't do what you want me to do. I don't believe in it and I don't

believe it's right for the country. And even if it costs me the election, I am

not going to do this."

And the president looked at him and I think it's one of those moments when you

know that the president really got it. The president said to Gingrich, "I

simply can't do what you want me to do. I don't believe in it and I don't

believe it's right for the country. And even if it costs me the election, I am

not going to do this."

And I kind of sighed at that point and I thought, "He gets it. He gets it."

Because there's always a point in politics when you do have to draw a line.

And it tells you a lot about who you are. And I think at that moment, I knew

he would win the election because, suddenly, what he was about was clear to

him, but it also became clear to the country as to what Bill Clinton

represented. So I think it was not only a terrible mistake on the part of the

Republicans, in terms of their own politics, but it sure as hell helped us to

find what the president was all about for the election.

Stephanopoulos: No one knew who would get blamed more for the shutdown,

Democrats or Republicans. But there was more than the shutdown involved.

First, there was also this threat that they would not extend the debt limit,

that this was the big hammer that would force the president to accept whatever

the Republicans wanted.

Our strategy was very simple. We couldn't buckle, and we had to say that

[Republicans] were blackmailing the country to get their way. In order to get

their tax cut, they were willing to shut down the government, throw the country

into default for the first time in its history and cut Medicare, Social

Security, education and the environment just so they could get their way. And

we were trying to say that they were basically terrorists, and it worked.

Morris: From the very beginning, Bill Clinton had two big problems -- a

third of the country thought he was immoral, and a third of the country thought

he was weak. Now, we couldn't solve the first problem, but we could solve the

second one. And the budget fight was a way of solving the second problem.

Because in the course of resisting those budget changes, in the course of

taking two government shutdowns and not blinking he convinced people that he

was strong, and it solved his most solvable problem. Still couldn't solve the

morality one, but we sure could solve the weakness one.

Stephanopoulos: We'd won. And you know, he didn't know it then, but

we'd won not only the shutdown, but by winning the shutdown, Bill Clinton won

the '96 election. Bob Dole was behind and never caught up.

The success of the budget battle for the White

House was followed by a barrage of trouble for the first lady. In January

1996, Hillary Clinton became the focus of both House and Senate inquiries and

was subpoenaed to testify before the grand jury by the Office of Independent

Counsel Kenneth Starr.

Stephanopoulos: Well, it was a typical Clinton White House moment --

bad news follows good. I mean, everybody had felt so good about the way the

shutdown had ended. Like we had stood firmly for our principles, we had

prevailed, the Republicans were in disarray, things were starting to look good

up in New Hampshire, and then wham, Hillary has to go to the grand jury.

What I think it did more than anything else, though, was galvanize everyone to

think that Ken Starr now clearly had crossed a line. You know, before that

moment, there had been a lot of people in the White House who just said,

"Listen, the best thing to do is just let's cooperate, let's do the best we

can." But when he basically tried to humiliate the first lady by having her

appear in person before that grand jury, I think there was a real sense that

the Rubicon had been crossed.

Sherburne: I saw these documents. [White House aide Carolyn Huber]

handed them to me. I saw Vince Foster's handwriting all over them, which by

now I recognized, and just realized immediately that this was going to be a

problem. You could see the conspiracy theorists going. I saw the next six

months of my life spin out in front of me and knew what the allegations would

be. There was always some sense that something was removed from Vince Foster's

office after his suicide. I knew that there would be allegations that this

must have been it.

McCurry: There was a real easy way to portray the information negatively

and the president's opponents did that. And, of course, I don't think the

press was willing to cut the White House and particularly Mrs. Clinton any

slack on the suddenly discovered billing records.

Sherburne: With the billing records, they did something quite

extraordinary. They subpoenaed her to come down and testify before the grand

jury and actually leave the White House and do it in a very public kind of way.

Not discreet and not befitting of the office and totally sensationalizing the

significance of these billing records.

Was that humiliating for Mrs. Clinton to have to do that?

Sherburne: I don't think so. I think that, once we recognized that this

is what he was going to insist that she do, she just did it, and she did it

with all of the grace and style that she has. She went in there, she answered

the questions, and told the truth, and came back out, met the press, said, you

know, "Here I am. Yes, I did it. I answered the questions, and I'm going home

because I'm tired." I mean, she couldn't be humiliated by it. It was too

obviously a political ploy to actually be humiliated.

After vetoing two Republican welfare reform

bills, the president was presented with a third. While White House cabinet and

staff members advised the president to hold out for a better plan, White House

foil Dick Morris felt that signing the bill was key to Clinton's

reelection.

Morris: So when the Republicans gave him a clean welfare reform bill

embodying his basic principles that he'd always supported -- time limits and

work requirements -- he was inclined to sign it. But then they loaded up the

bill with all kinds of other provisions, to cut aid to legal immigrants, and

Clinton did not want to sign those provisions. And there was a real push-pull

for his mind on that...

Reich: By and large, the political advisors, who have a very

legitimately important job of making sure that this guy is reelected, and

helping him maintain or enhance his political capital, the political people, by

and large, wanted him to sign. They felt that it was very dangerous not to

sign. Even though he was leading Bob Dole by 20 percent, they felt that if he

did not sign the bill, if he vetoed -- a third veto -- that Dole would hit him

over the head with it during the campaign. Dole would call him a hypocrite.

Bill Clinton had promised to reform welfare, end welfare as we know it. The

Republicans had given him three bills, and he had rejected them all, and Bob

Dole would have a field day, and that 20 point lead that the president had

might evaporate. That was the fear.

Shalala: And I thought I made a pretty good argument, in the room, that

we should go back and try to get a better bill. Every time we went back --

this was the third reincarnation -- we got a better bill.

Reich: I felt pretty awful. I felt pretty sick. A combination of the

day, the Washington humidity. I walked back to my office, down Pennsylvania

Avenue, and knowing that the president was going to sign the bill, it seemed to

me the worst decision of the administration. It seemed to me an immoral

decision. We would not know how immoral it was for years to come. The economy

would probably stay good. He might even take credit for signing the bill. A

majority of the public might even come to think it was the right thing to do,

but over the long term, it would be a very dangerous move. It would cause a

great deal of grief for a lot of people.

Panetta: And so there were a lot of discussions that took place in

the cabinet room. And then I remember a final discussion that took place

really in the Oval Office, in which I think present were the vice president,

George Stephanopolous, myself, maybe one other, and the president. And the

president said, "What do you think?"

And I said, "Mr. President, I can't be objective about this." I said, "I'm the

son of immigrants to this country. And this really hurts immigrants and it

takes away their health care. It takes away their food stamps, nutrition." I

said, "I think if you push, I think you can get a little more. But you don't

want to take the position where you're hurting people with this bill." George

felt the same way. The vice president said, "You know, I think in the end,

you're probably better off supporting this and getting it done because, you

know, we can always try to correct this later on, but at least you'll get the

main bill done."

And ultimately the president said, "I think that's what I'm going to do." And

we said, "Okay. Fine." You know, "If that's what you want to do, we'll move

ahead."

Shalala: But he also made a promise to me that day, that we would go

back and correct this bill right after the election. And he explained, very

carefully to me that he thought he had to go forward with this bill, that the

timing was important, both in terms of, obviously, the elections, but also in

terms of what he thought we could get at that time. But he also made a solemn

promise to me and to Henry Cisneros that he would go back and make corrections

on poor immigrants, on single individuals that were cut out of food stamps.

And we in fact did make those corrections.

Morris: I think vetoing it would have been the single highest risk.

I think if he'd vetoed that bill, he probably would not have been reelected

president. He ran on the basis of welfare reform. His most important spot in

1992 was "I will end welfare as we know it." And if he then got a welfare

reform bill that, as far as American citizens are concerned, was precisely what

he wanted, and was only bad insofar as immigrants are concerned, the public

would never have understood a veto of that legislation.

When Bill Clinton became the first

Democratic president since FDR to be reelected, it was a vindication. It was

proof that, despite the scandals and political battles, he could deliver for

the American people. For the first lady, it was a chance to put all of her

problems behind her and start anew.

Emanuel: And the biggest emotion was the victory, the sense of

history, a part of it, and the political accomplishment of it. I'd been

involved in politics, I like politics. And there was a political

accomplishment, a win. But there's also that sense for any one of us --

through this presidency and through, even from the announcement -- there was

always a sense of headwind. People wrote him off through Gennifer Flowers,

through the draft experience, the gays in the military, the '94 election, and

he had defied the oddsmakers again.

Reich: The win was a vindication. It was reversal of the tribulations

of 1994, the rejection that 1994 represented. You see, when a president wins a

second term, the president's place in history is assured. Unless the president

does something absolutely awful, there's an entire chapter of a history book

devoted to that presidency. It becomes an era, the Reagan era, the era of the

Kennedy-Johnson, that's sort of one presidency in a way, the Roosevelt era.

Having won a second term is what every president in a first term dreams of. If

you don't win a second term, you are relegated in the history books to being

something of a failure. And I think the president felt wonderful.

Election night, '96, any vivid recollections? Excelsior Hotel.

Stephanopoulos: What stands out most to me was how different the

feeling was from 1992. Yes, it felt good to have the vindication of winning

and to have the chance to go on for the next four years and keep on doing what

we were elected to do. But there was less, can't help but have been a more

sober experience. So much had happened over the four years in between. There

had been so many near escapes, so many near-death experiences, so many

disappointments, crises, along with the victories, that it was harder to build

up that same kind of passionate excitement for the win, as quietly satisfying

as it was. And so instead of hundreds of people out on the lawn and the core

of the staff right there on the base of the stage, there were a bunch of us up

in a suite of the Excelsior, you know, quietly watching on TV -- very, very

different feeling.

You write in your book that on that night you make a kind of a peace with

Hillary or she seems to make kind of a peace with you.

Stephanopoulos: Well, the peace had actually been building for a little

while. Over the course of '96 she kind of appreciated the Democrats in the

White House carrying on the fight. And so there'd be a lot of phone calls of

encouragement. But, yeah, it was a very vivid moment. I was just about to

walk out to go do the final interviews for the last night, and I caught her in

the hallway. She had just been helping Chelsea get dressed. And she knew it

was basically my last night. I was going to leave the White House in a few

weeks, and she just caught me in the hallway and looked me in the eye and said,

"I love you, George Stephanopoulos." And I said, "I love you too." But it was

like so -- there was so much kind of hope in her eyes that night. You know,

they were tearing up. It was almost as if we've endured the first four years,

so we can, you know, achieve in the next four years. I think she sort of felt

all of the problems were behind her and they were now free to go on and free to

close off a lot of the unpleasantness of the past.

He was the Comeback Kid again?

Emanuel: Comeback Kid, there's no doubt about it. One of the great

things that the president has is people underestimate him all the time I think.

I could probably write a good handbook for his opponents, the unbelievable

amount of times they underestimate him, his determination. I mean, go back to

the '94 government shutdown. Forget the policies. It was all built on the

political calculation that Newt thought the guy was going to fold and he didn't.

|  |