In October 1991, five-term Arkansas

Governor Bill Clinton declared he was running for President of the United

States. For the team starting to build around him, it was political love at

first sight -- Clinton appeared to be the centrist, charismatic candidate for

whom they had been waiting...

Stephanopoulos: It's hard to talk about it now, because it's become

common wisdom to everybody else. But at that time it was a new experience,

this notion of meeting someone who is not just in your face, but kind of in

your skin from the moment he meets you. You know, you just feel completely

connected to him when he turns to you.

... Oh, the smarts. The guy had thought everything through, both on the

politics and the policy. I remember when I interviewed for the job, which

wasn't really an interview. It was him -- me listening basically for an hour

and a half to Governor Clinton just go through the entire landscape of the

campaign. And he basically, the very first time I talked to him, in the

seamless web of issues and politics said, "It's all going to come down to

Illinois on March 17th. If I win the game in Illinois, I'll get the

nomination." Exactly what happened. But he had it in his head back in

September.

Begala: I had been in the business for a number of years by then and it

was still political love at first sight. I thought he was the ablest guy I had

ever met in politics.

Emanuel: Early on, until part of December, there was still the Cuomo

cloud that hung over -- that he was going to enter the field. You had two

senators. One was Bob Kerrey, and his past, specifically his biography as it

related to Vietnam, was kind of the new face of the party. You also had

Senator Harkin in there and former Senator Tsongas. So that combination. I

remember my father, when I said I was going down to Little Rock to work for

Governor Clinton's run for president, he thought maybe somebody needed to check

the medication cabinet. He thought somebody was playing around with it. He

had never heard of him, he said. I said, "Well, I think he's going to be the

next President of the United States."

Myers: I saw a candidate who knew why he wanted to be president and he

knew how to get there. He didn't know whether he would be successful but he

had in his head kind of a roadmap based on issues. He had a sense of where the

country was. There was this uneasiness that there was this kind of economic

anxiety and he was pulling together a team that was going to help him get

there. But, you know, he was the engine that was driving it, and from the very

beginning I was really aware this was a special politician. This was somebody

who had more innate talent, both with the substantive side and the politics,

than anyone I'd been around. And it was just fascinating to watch him.

Begala: Most politicians, when they meet with a guy like me, or a guy

like Carville, tell you about how they can win. They would say, "Look, my wife

is from Illinois, which will help me in the Midwest, even though I'm a

southerner and I have close alliances with these moderates." They would give

you the strategy. Clinton gave us the policy....

I was bowled over. And then he went through the policy specifics, and he

focused on these two things. He said, "Economically we're sliding down, and

socially we're coming apart." I used to tease him that he had three solutions

for every problem, but he went on like this for hours, and we were completely

bowled over.

January 1992 was a bad month for Bill

Clinton. First there were the allegations from Gennifer Flowers that she had

carried on a 12-year affair with the governor, and then came the charges that

Bill Clinton had avoided the Vietnam draft. The lurching from crisis to crisis

not only took its toll on the candidate's popularity, but also shook the

campaign staff's faith in him.

Carville: December went fine. If you remember, Cuomo was thinking about

running, he decided that he wasn't gonna run and we sort of were doing --

picking up pretty good in the polls. We had a pretty good December. Then in

January, as we say in the trade, we got a little incoming.

Stephanopoulos: The first [Star tabloid story] came out and it

was kind of easy. It was -- the Star alleged that Clinton had affairs

with five women, all who had denied it in the past. It had come up in his

Arkansas gubernatorial campaigns. And, you know, we just said, "We don't know

why everybody's changing their story today or why the Star is printing

that stuff. It's just cash for trash. And let's keep moving."

Carville: [on the cash for trash strategy]: I think the strategy

was to say that there was a lot of money that was passing hands here. It was

all odd that this was coming up this 10 days or whatever it was before the

election [New Hampshire primary]. I think the strategy was pretty obvious and

I think the strategy worked pretty good.

Begala: A lot of times in a campaign you get in trouble, and the

inclination of handlers is to hide the candidate, to so-called "protect" him.

Well, in this case, there was no one else who could answer anyway, and he was

our ablest spokesman. So we set about looking for a venue where he could go

and answer these things.

Myers: I think basically all we tried to do was survive. It was really

a tremendous feeding frenzy. I remember we were making a swing through the

south right around the time all hell was breaking loose. And Governor Edwards

was there and he said, "Now, what's this story about this, this girl?" Clinton

kind of said, "Yeah," blah, blah, blah. And he said, "How much did they pay

her?" And Clinton said, "Well, that's the point, it's $150,000." And Edwards

says, "$150,000? If they paid all my girls $150,000 they'd be broke." And

Clinton just cracked up because it was much-needed comic relief at the time.

Carville: You've got to fight back. Yes, sir. And our strategy from

day one was to contest at every point. And, to have them out there... the best

person to give the explanation of what happened and where it was, was

then-Governor Clinton and Mrs. Clinton. And that's why we did the 60

Minutes thing, because it was the biggest deal that there was, and you had

to be shown that you were out taking it on.

You advised the president that the best thing he had going for him in that

interview was Mrs. Clinton.

Carville: Yeah.

How come?

Carville: Because in the end, if the wife is with... you know, people

overwhelmingly, they say, "Look, that's his wife, they're fine." ... Clearly

had he gone on without her it would have been a big gap...then my advice would

have been if she wouldn't go, don't go.

Stephanopoulos: And what worked for them was, I think, a couple of

things. One, they did it together. Again, once the couple is together, it

says to the rest of the world, "This is our business, not yours." And two, and

it's hard to get back to this at a time when the country is doing so great

right now, but in January 1992 a lot of people around the country were worried

about the economy. People were hurting. And the very basic message -- that

the campaign should be about everybody else's future, not my past -- was very

powerful to a lot of people watching, especially in New Hampshire.

Myers: So, you argue the facts and you try to make the case that Clinton

has always had political enemies, Arkansas is an interesting state in that

regard. A lot of stuff had gone on. But, obviously, over time as Gennifer

Flowers gave way to the draft, to other questions, it became harder. And it

became hard for people like myself and George Stephanopoulos and Paul Begala

who had to go out there and defend him every day. You learned to be very

careful and you learn to listen very carefully to what he said, and you learn

to try not to go further than what he said. And we had a lot of conversations

over the months and years about "What do you think that means?" You know,

"What can we say? Where's the safe ground here?"

Stephanopoulos: One of things that James and I tried to do very early on

was to authorize just a full investigation of our own record, of Clinton's own

record, of Clinton's own statements, so that we would -- at a minimum, we

wouldn't compound any problems by saying things that weren't true. And that

there wouldn't be any problem of, you know, telling the story of what happened

in Vietnam. The problem is when you appear to be lying about it. But you

know, there was a great reluctance to do that. We ended up doing some. But by

the time we really did a full vet of Clinton's background, it was too late.

The stories were already coming out.

Begala: We were handed [the draft letter] as we landed in New Hampshire.

We had been in Arkansas. The governor had gotten badly sick, a high, high

fever. And this story of the draft had broken in the Wall Street

Journal, and he had to go home. He was bad sick. So he was home

trying to recuperate. We were getting poll numbers that showed us absolutely

collapsing in a way we never did with the earlier scandals. And so we stayed

up all night writing a speech that basically said, "I'm going to fight like

hell." You know, "We're not going to give up. Try this one more time." And

we flew up there, and we're landed, and we're all revved up, and he's ready to

go. And as we got off the plane, Mark Halperin of ABC hands Georgie and I this

letter, and I'm looking over George's shoulder as he reads it, and I see that

line, "Thank you for saving me from the draft," and my knees kind of buckled.

And George said, "That's it. We're through. We're out. It's over."

Carville: I said, you know, "If anybody who is 21-22 years old could

write a letter like this you could almost see kind of a future president

there." So we took the letter, published it, put it in the newspaper, and we

get a Nightline date.... Nightline did an interesting thing. They

read the whole letter.

Begala: Ted [Koppel] read the whole letter to the country, and you could

see, even among the press corps, which really did think he was a slick Willie,

you could see for the first time they thought, "Well, okay. This is a highly

nuanced letter from a tortured young man who's really thinking through these

issues just like every other young man of that generation did."

So your initial reaction was wrong? I mean, you initially thought that

maybe this was --

Begala: Before I had read it. The first thing I saw was that line.

But, no, even me, who did not have much of a feel for that time, I thought,

"Yeah, this letter" -- I mean, the line we used was, "This letter is going to

be your best friend."

Following the early scandals of the

campaign, it looked like Bill Clinton's candidacy was over. Yet the governor

refused to give up, even if it meant he had to shake every hand in the state of

New Hampshire. Amazingly, he came in second in that primary and declared that

"New Hampshire has made Bill Clinton the Comeback Kid."

Myers: Over the course of his public life, he's never been more focused

than when his back was up against the wall. I don't want to say it helped him,

but it was the fire that steeled him for the rest of the campaign. He was a

much better candidate for going through New Hampshire, not just because of the

scandals, but getting down there and campaigning and looking in people's eyes.

And he really absorbed a lot of -- he really did feel their pain. I mean it

was an amazing thing to watch.

But, yeah, he took the scandal, what was handed to him or the situation that he

helped create, and he managed to -- he took the energy from that and he did

manage to boomerang it. He was the focus. Everybody was watching him, waiting

for him to go down. And what did he do? He used that spotlight to turn the

thing from being about him to being about what he could do for the people.

Stephanopoulos: There's nothing you can do on election day. Election

day in campaigns you basically wait. And we waited in James' hotel suite. And

we waited for the first exit polls, which would come in around 11:00 o'clock.

And we were a pretty grubby crew at that point. It was kind of James, me,

Paul, Bob Boriston. Mandy [Grunwald, media advisor] was around. And what I

remember most vividly waiting for the exit polls was James walking around the

suite in his undershirt lashing himself on the back with a piece of rope like a

medieval penitent and --just lashing himself, lashing himself, lashing himself.

And then the first exit polls come in. And miracle of miracles we're a strong

second place. And everything changes. We order cheeseburgers. Paul and Bob

start to write out the acceptance speech that night. Clinton is still out

campaigning. He's amazing. But the germ of what turned out to be one of the

most memorable lines of the campaigns started then. I don't know who takes

credit for it now or who gets credit, but I think it was some combination of

Paul and Mandy came up with the line, "Tonight New Hampshire's made me the

Comeback Kid." And we all felt like comeback kids that afternoon because the

campaign had been on life support and now we had a second chance.

|

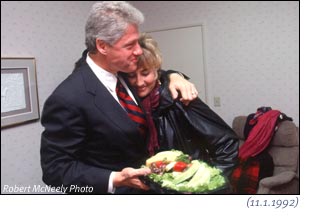

Bill Clinton's staff was in

awe of his ability to campaign. They had never seen anything like it and in

private called him "Secretariat." His volatile temper -- or what was known as

the "standard morning outbursts" -- was mainly kept in private. And by the

summer of 1992, the governor's grasp of the issues, his ability to empathize,

and his sheer tenacity paid off. It was clear he would be the Democrats'

choice.

Stephanopoulos: We called him "Secretariat" because he was just the

absolute thoroughbred of thoroughbreds of campaigners. Whether it was working

a rope line or giving a speech or devising the policy or just having the

stamina to last through four 20-hour campaign days in a row and do it with good

humor and grace. None of us had ever seen anything like this before. I mean,

he is the politician probably not only of his generation, but if you're

thinking just pure raw political skills, probably the politician of the

century. And it was an awesome sight to watch.

Carville: You had the sense that these were really, kind of,

extraordinary people and extraordinarily talented. Okay? And I don't, it's

kind of a hard -- you can't really define it, but there was a certain way that

he could change a chemistry in a room. He could walk into a room of a hundred

people and immediately have the sense of who the most vulnerable person was,

whose mother just died or who just had a child that had a crisis or something

like that. And it's an instinctive thing. I can't explain it. I've just seen

it happen again and again and again.

Myers: I'm a baseball freak. So, I say he's the guy who could throw a

no-hitter and hit 50 home runs. I mean nobody can do that, nobody can master

the substantive side of policy and genuinely thrive on the human contact of the

politics. But he does both. And, I mean he was the best strategist in the

campaign, most of the time. He was totally steeped in the details of "How many

electoral votes, how many states are we targeting, why are we targeting them,

what's our organization in those states, who are the local elected officials

who are going to be with us, does this make sense?" Every step of the way he

was totally involved in decision-making.

... Sometimes, I shouldn't say save him from himself, he's obviously

tremendously successful, but one of his tendencies has been and throughout his

presidency at times, has been to try to do everything, to talk about every

issue, emphasize everything, which means you're emphasizing nothing. So, that

was the flip side of him. He's interested in everything. He has encyclopedic

knowledge. He has a voracious sort of appetite for information about

everything from the Beatles to the details of nuclear disarmament.

Early in the campaign, Clinton

declared that he and his wife were basically a bargain deal -- "buy one, get

one free." While Mrs. Clinton was credited for keeping the candidate and the

campaign focused, she also became an issue herself. In the spring of 1992 --

following criticism of her law firm's work with the state of Arkansas -- she

defended her decision not to "stay home and bake cookies." From that moment

on, Hillary Clinton was as controversial a figure as her husband.

Myers: And then after January and February of 1992, the Gennifer Flowers

thing broke and they appeared on 60 Minutes together. There was a sense

that he was in debt to her. And he was obliged to take seriously her

advice.

... By defending him and standing by him and saying to the world, "You know,

we've had our ups and downs, it's none of your business. We're still together.

And, you know, leave us alone." And-- I mean, what could anybody else really

say at that point?

So, there was an indebtedness to her because she had saved him?

Myers: Yeah. And I think that that's been a pattern throughout probably

their relationship, before I knew them, but certainly in his presidency. I

mean, he tends to do worse when he's furthest and then he screws up and she

helps save him and then he's sort of much more -- indebted, obliged, mindful,

all those things. And I suspect it probably was that way before I was

around.

Stephanopoulos: I think I was sitting with Paul, chatting with a few

reporters, drinking a cup of coffee in the coffee shop while they did their

thing meeting with people. And then all the sudden, Hillary starts to do this

kind of impromptu -- reporters had gathered around at this impromptu press

conference.

I don't remember much of what she said except the words that everyone would

soon know, "tea and cookies." And it was just like bam, all of us all of the

sudden perked up and said, "That's going to be a problem." because it was just

too good a phrase. You know, it was just impossible for any reporter sitting

there that day not to use the most resonant, rich, colloquial phrase she could

possibly use to describe her choice to work in a law firm as opposed to staying

at home. And we knew it was a problem. But nobody wanted to tell her, because

that wouldn't be fun at all.

And I was sitting there with Paul, like the old Life commercial, saying, "No,

I'm not going to do it, you go do it." "No, I'm not going to do it, you go do

it."... We knew it was a problem the minute she said "tea and cookies." And

we knew a lot of people would take it as proof that she is this radical

feminist who has no respect for traditional women. And we're going to have to

try to clean it up.

Begala: As soon as I heard that, I thought, "People are going to take

that out of context. They're going to suggest she doesn't care about

stay-at-home moms." So I went up to her and I told her that. I pulled her

aside, and I said, "You know, Hillary, you've got to go restate this. People

are going to think that's an attack on stay-at-home moms."

And she had the most wounded and naive look on her face. It is -- to think of

all she's gone through since then, it's hard to imagine. She had no idea that

that might be taken out of context. She said, "No one could think that." She

said, "I would have given anything to be a stay-at-home mom. My mother was a

stay-at-home mom. I just didn't have a choice because Bill was making $35,000

a year and we needed to support the family."

I said, "I know that." And she said, "Oh, you worry too much." I mean, it was

unimaginable to her that that would be a firestorm. I was certain it would be.

I had been doing this for a while. So she went back out and tried to clean it

up, but it was too late.

Stephanopoulos: What it was was, you know, we're trying to figure out

the damage that had been done, not only by the "tea and cookies," but just the

overall primary campaign. It looked then like we were on the road to the

nomination since Stan [Greenberg, polling advisor] had done some focus groups,

dial-up groups, you know. But the footage that was used for Hillary was

footage from election night 1992, in New Hampshire where she had this elaborate

Nefertiti-style hairdo that night -- one that I've never seen since and had not

seen before. And it really was something.

But we were all sitting around the focus group watching these dials, and up

until that point they had been pretty steady. And then this picture of Mrs.

Clinton comes on and the dial groups go like [noise], and Clinton doesn't miss

a beat. He just says, "Oh, they don't like her hair." And I'm sitting next to

James on the couch and he starts to grind his fist into my thigh because it was

-- for us, it was like someone farted in church and we were about to start

laughing uncontrollably. And we were just holding it in and he's grinding his

fist into my thigh. And we finally, we're not breathing, we finally run out of

the room, get into the hallway, and just break up laughing.

Now, looking back, it was kind of sweet that Clinton said that. His instinct

was to protect her -- he's a smart politician and he knew that we had a pretty

serious problem coming out of "tea and cookies" and that a lot of people had

very strong feelings about Mrs. Clinton. And he was kind of just being

protective of her in that moment. We didn't dwell on it that day.

By the fall of '92, following the

Democratic Convention and the nomination of Al Gore as vice president, it

started to look like Governor Bill Clinton might win the election. And then,

with 43 percent of the vote and 13 months after the campaign began, William

Jefferson Clinton won the presidency. His campaign staff recall when they

realized their candidate would be the next president.

In '92 when do you know that you're going to win? When are you pretty

sure?

In '92 when do you know that you're going to win? When are you pretty

sure?

Begala: In Parrot, Georgia. We took a bus trip through Georgia, as I

worked for Zell Miller and his campaign in 1990, so I knew the state fairly

well. And we were on a bus with Zell, and with some other Georgia politicians.

We went through this little town called Parrot, Georgia, and we drew more

people in Parrot, Georgia than the total population of the town. And-- it was

raining, and I looked out there, and I thought, "You know, we're going to win

this race." And that night in some little motel in I don't know where, I

called Stephanopoulos, and I was just giggling. I was giddy. And I sat there

on some crummy bed in some crummy motel, and I said, "George, I will guarantee

you this, we win this election." I can't remember what month it was, but it

was in the fall campaign. That was the moment.

Stephanopoulos: I remember the first time I ever really let myself

believe we could win and we were going to win. It was late September in the

Washington Hilton on a Sunday morning and Clinton was about to go give a speech

in North Carolina on NAFTA. And he called me in and had his standard morning

outburst on the speech and was yelling about it. But his heart wasn't really

in it and I could tell. And I kind of sat there, I was in his bedroom and just

took it. He was lying back, propped up in his jeans on his bed, propped up on

about two pillows. And he suddenly stops yelling, looks me right in the eye

and says, "You think we're going to win, don't you?" I said, "Well, yeah."

And he goes, "I do too." And for me, that was just incredible.

He was saying out loud what we all hoped for but could never say. It would be

like talking about a no-hitter in the eighth inning. And from that moment on

inside we didn't feel like underdogs anymore. We felt like we had this

responsibility to win. And as a staffer, it was starting to get a little bit

out of control because, you know, I had never been through anything like that

and nobody else had either.

Begala: The day before the election we were at the Mayfair Diner in

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. And this is maybe, professionally, aside from the

birth of my child during that campaign, the sweetest moment. I was the guy

that told Bill Clinton he was going to win. I had gotten the final polling

numbers. He had a comfortable lead. He was not going to lose. And as he

climbed into the car at the Mayfair Diner, I told him. I said, "Governor, it's

over. You're going to be the President of the United States." And he said,

"How do you know that? What do you think?" And I gave him the latest numbers,

and he said, "That may not hold." So I told him what the latest numbers were

for Reagan in '80, and then what the final election was. And I think that

historical comparison -- and he didn't say anything then. He just kind of

quieted down, and his eyes got big and he sat back. That was very sweet.

Myers: So we finished our little tour and I remember going to the

Governor's Mansion and down to the basement about 8 o'clock and-- I mean, by

that point we already knew it was pretty much over. I mean, we knew we were

going to win. But seeing that map, standing in the basement -- they had a TV

down there -- and standing in the basement with him and he kind of had a half

grin on his face looking at the map turning whatever color we were. I think it

was different on different networks. But, you know, as the electoral college

count came in and he was closer and closer to that magic number, and it was

just the weirdest. ... It's like, "Wow, here we are and he's the next

president and he's just standing here in his basement, watching TV like

millions of other Americans right now." It was just very strange -- in an odd

way slightly anticlimactic, even though it's the biggest thing that can ever

happen in politics to you.

|  |