|  |

| |  |

Oriana Zill was Associate Producer of FRONTLINE's "Hunting Bin Laden"

|  |   | |

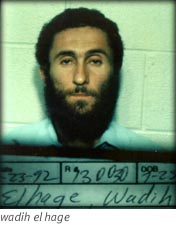

On a cold, rainy day in February, 1999 in New York City, Wadih El Hage was led

into Manhattan Federal Court for a pre-trial hearing. Surrounded by several

large security officers, El Hage appeared slight in his prison jumpsuit. A

bearded man with intense, dark eyes, he whispered quietly to his lawyer

throughout the hearing. In the sterile courtroom setting, it was hard to

imagine this man was involved in the horrific bombings in East Africa in August

1998 which left 224 people dead and thousands injured. On a cold, rainy day in February, 1999 in New York City, Wadih El Hage was led

into Manhattan Federal Court for a pre-trial hearing. Surrounded by several

large security officers, El Hage appeared slight in his prison jumpsuit. A

bearded man with intense, dark eyes, he whispered quietly to his lawyer

throughout the hearing. In the sterile courtroom setting, it was hard to

imagine this man was involved in the horrific bombings in East Africa in August

1998 which left 224 people dead and thousands injured.

A month after the bombings, El Hage was arrested after testifying before a

grand jury. Originally charged with eleven counts of perjury, or lying to the

grand jury, the charges were later expanded to include conspiracy to kill

United States nationals. Prosecutors claim that El Hage, one of two American

citizens who have been charged, was useful to bin Laden because of his ability

to travel freely around the world with an American passport.

El Hage's lawyer requested the February hearing to discuss the restrictive

conditions of El Hage's jailing and to ask the judge for a decision on

bail. After several hearings, Judge Leonard B. Sand denied bail and El Hage

was taken to solitary confinement at the Metropolitan Correctional Center to

await trial.

El Hage was born in 1960 into a Catholic family in Sidon, Lebanon. He grew up

in highly Islamic Kuwait, where his father worked for an oil company.

According to El Hage's mother-in-law, he converted to Islam as a

teenager after reading the Koran.

His family disapproved of El Hage's conversion and shunned him. But he was

taken in by a Muslim Sheik in Kuwait who paid for his education in the States,

and he became a deeply religious young man.

In 1978, El Hage moved to Lafayette, Louisiana, to attend the University of

Southwestern Louisiana (USL). He studied urban planning and got a job at a

donut shop where many young Arab men worked. His advisor at USL remembers El

Hage as an average student who showed no signs of strong political views.

At the beginning of the Afghan war against the Soviet Union, El Hage left

Louisiana and traveled to Pakistan to enroll in mujahedeen war training

programs. Thousands of young Arab men from around the world flocked to

Pakistan to help the Afghans expel the Soviets. Sources told FRONTLINE that

El Hage was a follower of Sheik Abdullah Azzam, one of the most important

spiritual leaders of the Arab mujahedeen forces. Azzam preached that the war

in Afghanistan was a jihad, or holy war, and that those who participated would

have a special place in heaven.

During the Afghan war, Sheik Azzam became aligned with Osama bin Laden, who

was at that time becoming active in fundraising and organizing mujahedeen

fighters. Some reports have speculated that this may have been the initial

connection between El Hage and Osama bin Laden.

By January 1985, El Hage returned to the United States and to USL. Later that

year, he traveled to Arizona to marry an 18-year-old American Muslim named

April. April's mother told FRONTLINE the two were introduced through an

arranged marriage. In May 1986, El Hage graduated from USL and moved

permanently to Arizona to start a family.

El Hage and his wife returned to Pakistan several times over the next few

years, and for about a year, his mother-in-law and her husband accompanied

them. "I was the Matron surgical nurse at an Afghan Surgical Hospital," she

told FRONTLINE. "Wadih did not actually fight, but acted as an educator. My

husband went with Wadih to deliver textbooks and Korans to the young people.

It was a Jihad, a fight for Islam."

When they returned to Arizona, El Hage worked at several minimum wage jobs,

including city custodian. In 1989, he was granted U.S. citizenship.

Dr. Rashad Khalifa was an imam in Tucson, Arizona who some felt was unorthodox. He used numerology to try to prove that the Koran was written by God. The imam also let

men and women pray together and wear non-traditional dress.

New York prosecutors say that in the first days of 1990, El Hage was called up

by a "tall man" from New York who suddenly arrived in Arizona and said he was

there to check Rashad Khalifa. El Hage entertained him at his house and drove

him to the mosque, prosecutors say.

Several weeks later, Khalifa was found murdered in the kitchen of the Mosque.

Several members of the radical Islamic sect, Al Fuqra, were convicted for

conspiring to commit the murder, but no shooter has ever been convicted.

Prosecutors have repeatedly implied El Hage knows who committed the murder and

may have been involved.

El Hage's family calls the claim ridiculous, saying El Hage was out of the

country at the time of the murder. Prosecutors have repeatedly said El Hage at

least should have contacted the authorities with what he knew after he found

out that the man was murdered.

Soon after, El Hage moved his growing family to the suburban community of

Arlington, Texas.

In December 1989, according to prosecutors, El Hage met Mahmud Abouhalima at an

Islamic conference in Oklahoma City. According to a confession Abouhalima

later gave U.S. Attorneys, Abouhalima contacted El Hage in 1990 to purchase

assault weapons to be used against radical Jewish Rabbi Meir Kahane. Kahane

was murdered in November 1990 in New York City.

El Hage's family told FRONTLINE that he did buy some weapons for Abouhalima,

but they were never picked up. Family members also say El Hage was told the

guns were for self-defense against the Kahane group.

In early 1991, according to El Hage's grand jury testimony, he was called to

New York to help direct the Alkifah Refugee Center, a Brooklyn-based group that

raised money to support veterans of the Afghan war. According to documents

from the World Trade Center case, Alkifah had a Tucson office and contacts with

the main mosque in Arlington, Texas, and family members confirmed that El Hage

had been in contact with the group.

On the same day that El Hage arrived in Brooklyn, on March 1, 1991, the leader

of the Alkifah Center, Mustafa Shalabi, disappeared. A week later his

mutilated body was found in the apartment he and Mahmud Abouhalima shared in

Brooklyn. The murder case has never been solved, but prosecutors believe the

murder was the result of a dispute over allocation of the group's resources.

The family maintains that El Hage was called in as a mediator on this and other

occasions when his friends from Afghanistan developed disputes. "I know he was

good friends with Shalabi," says El Hage's mother-in-law. "He [Shalabi] was

running the organization to help Afghan veterans and Wadih wanted to help him.

Wadih cried on the phone about Shalabi's death. Shalabi must have called him

to go to New York to help when the trouble started."

Other friends of the family from Arlington, Texas, also described El Hage as a

mediator and a person whose religious purity and strong faith were trusted by

others "He was calm and devout, not violent or rash," said a close family

member. "I would get more upset over politics than he would."

Whether El Hage was a mediator or collaborator, evidence shows he was friends

with many people who were later convicted in the World Trade Center and New

York City Landmark bombing cases. On March 8, 1991, El Hage signed in to

visit El Sayyid Nosair at the Riker's Island. Nosair was serving a sentence

for gun charges stemming from the Meir Kahane murder case. Both El Sayyid

Nosair and Mahmud Abouhalima were central figures in the 1993 World Trade

Center bombing and both have been convicted in that crime.

There are other unusual connections between the men. In January of 1992, El

Hage was arrested in Arlington, Texas, for writing several bad checks. He was

riding in the car with a companion named Marwan Salama. According to phone

records from the World Trade Center case, Salama had extensive phone contacts

with the World Trade center bombers in the two months before the actual

bombing.

In early 1992, El Hage moved his family to the Sudan and he began working as a

secretary for Osama bin Laden. Family members say El Hage worked only in bin

Laden's legitimate businesses in the Sudan. FRONTLINE research shows that bin

Laden had quite a few businesses there, including a tannery, several farms, a

road construction firm, a transport company and two investment companies.

"He [bin Laden] was a busy person and had hundreds of people working for him,"

said one El Hage family member. "You didn't get to see him unless he invited

you." El Hage's mother-in-law received letters from El Hage that contained

seed samples from the Sudanese farms. El Hage frequently took international

trips to Europe and elsewhere on business for bin Laden, family members say.

Prosecutors, however, believe that El Hage was becoming a key aide to bin

Laden, who in turn was becoming an international terrorist leader. "The

intelligence that was being created pointed increasingly to him as someone who

had to be dealt with," said Larry Johnson, a former CIA officer and Deputy

Director of the State Department's Office of Counter Terrorism from 1989 to

1993. "There were other intelligence indicators that were starting to surface

in the '94 time frame that pointed out that Usama was a problem."

Little evidence has emerged that proves what El Hage was doing in Sudan. His

family admits freely that he worked for bin Laden, but cannot provide details

as to everything he did. Prosecutors have alleged in court papers that El Hage

"is being investigated for his efforts to try to obtain chemical weapons for

Osama bin Laden's organization." But no evidence has been provided to back up

this claim.

Finally, it was April El Hage who convinced her husband to leave the Sudan and

bin Laden's company. According to family members, bin Laden had been

encouraging Wadih to take a second wife and had even started to arrange someone

for him. "April would have none of that," said April's mother. "She is

Muslim, but she is also American, and she wouldn't stand for it."

In 1994, El Hage left the Sudan for Kenya and became director of a Muslim

charity organization called "Help Africa People." Kenyan government documents

say the organization was dedicated to malaria control projects. El Hage also

worked in the gem business to make extra income.

During his time in Kenya, El Hage stayed in contact with members of bin Laden's

inner circle. In particular, say prosecutors, El Hage associated with Ubaidah

al-Banshiri, a key figure within bin Laden's organization who was living in

Kenya. U.S. prosecutors believe Al-Banshiri was a key military leader, one

of two top-ranking commanders, of "al Qaeda," bin Laden's organization. In May

of 1996, al-Banshiri drowned in a ferry accident on Lake Victoria.

Another bin Laden associate, Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, also known as Haroun

Fazul, moved into El Hage's house in Nairobi during this period and began

to work for El Hage as a secretary. "He had no money and needed a place to

stay," says El Hage's mother-in-law. "Wadih was always letting people stay

with them. That is the proper Muslim way."

Haroun Fazul, according to prosecutors, was a key player in the Nairobi embassy

bombing in August of 1998--accused of renting the house where the bomb was

built and driving the lead truck in the bombing.

When told of the charges that Haroun Fazul was a key organizer of the bomb

plot, El Hage's family laughed. "April always called him the black Ronald

McDonald," said April's mother. "She thought he was kind of goofy. And she

finds it very hard to believe that he could have been a terrorist."

Another man charged in the bombing, Mohammed Saddiq Odeh, has admitted during

his interrogation that he knew El Hage in Kenya and that El Hage had attended

his wedding. Odeh was captured trying to enter Pakistan just after the

bombings and provided investigators with the first link that the bombings were

conducted by people working for Osama bin Laden.

U.S. officials in Washington D.C. had first started investigating Osama bin

Laden in the mid-1990s based on growing evidence that he was funding terrorist

activity. The New York Times reported that in 1996, CIA and State

Department officials secretly met with a Sudanese agent in Washington and asked

for the names of 200 bin Laden associates from the Sudan. In their efforts to

get more information on bin Laden, U.S. investigators attempted to locate and

interview as many bin Laden associates as possible. That investigation

eventually led them to Nairobi, Kenya-- and, in August 1997, to Wadih El Hage.

This was a full year before the Nairobi bombing.

"I arrived in Nairobi and not even 12 hours later there was a knock on the

outer gate," said El Hage's mother-in-law, who was visiting the family. "They

came into the house...it was the police department of Nairobi and American FBI

agents." El Hage was away at the time, family members told us, on a gem

collecting trip to Afghanistan.

FBI officials had a search warrant and collected all the papers in the house.

They also took El Hage's personal computer, and told the family that they were

searching for stolen property. They also gave April El Hage and her mother a

firm warning.

"They spoke to us that night and told us it would probably be best if we got

back to the United States right away," said El Hage's mother-in-law. "They

said it might not be safe to live here. She [April] got frightened. She's

got all these little children, and she's frightened and I'm upset. So she

says, no, I'm not leaving without my husband. I'm afraid I don't quite

remember the words but the inference was plain, that something might happen to

her or the children."

On El Hage's personal computer, the authorities found a letter that has

been released as part of the federal case against the Africa bombers. In the

letter, which prosecutors now believe was written by El Hage housemate Haroun

Fazul, the author describes the presence of an "East African cell" connected to

bin Laden.

The letter also states that the cell members had recently become aware that bin

Laden had declared war on America by watching the international media. They

seem upset because they were not advised of the decision before it happened and

are worried about the security of the cell.

"There are many reasons that lead me to believe that the cell members in East

Africa are in great danger," says the letter. "...the Hajj [bin Laden] has

declared war on America. My recommendation to my brothers in East Africa was

to not be complacent regarding security matters and that they should know that

now they have become America's primary target... I am 100 percent sure that the

phone is tapped."

El Hage's real name is evident in the letter, as is his assumed name from

Afghanistan, Abd'al Sabur, which means "servant of the most patient." The

letter seems to imply that El Hage is an "engineer" of the cell.

Two days after the raid on El Hage's house, he returned to Nairobi from

Afghanistan and was questioned by police. He was also told to leave the

country, according to the family. One month later, in September 1997, Wadih El

Hage and his wife left the country and returned to America. According to

family members, they sold everything they had in order to raise the money to

get home.

Intelligence sources have told FRONTLINE that the Nairobi raid was a

"counter-terrorism disruption" and that forcing Wadih El Hage to leave the

country was part of the strategy to fracture these cells as soon as they are

found. They did not, however, deport Haroun Fazul. In hindsight, the

authorities clearly did not understand the danger posed by El Hage's associate

at that time, and the evidence is unclear whether they were aware of Fazul at

the time of the raid.

El Hage moved back to the suburban community of Arlington, Texas and got a job

in a local tire store. The family moved into a small apartment near the

University of Texas and the children enrolled in a local Muslim school.

According to friends and neighbors contacted by FRONTLINE, the family lived a

normal Muslim life, regularly attending Mosque and schooling their children in

the Koran. "He was a hard worker, had a good business sense and was very

devout," said his co-worker at the Lone Star Tire Store, Mahmoud Mazouni. "He

became something of a religious leader, like an imam and sometimes led the

prayers."

The Muslim community in Arlington was shocked when El Hage was arrested

and insist he is innocent of any charges. Many members of the community

offered to try to raise bail for El Hage after he was arrested, to show their

support.

Mr. Mazouni said that El Hage showed no special reaction on August 7, 1998,

when the East Africa bombings took place. At home, however, he and his family

were worried. "When the bombings first happened, we were shocked," said a

close family member who asked not to be named. "We said, oh god,

Nairobi--don't let it be Muslims who are involved. Then, when we found it was

Muslims, we knew trouble was coming."

Two weeks after the bombings, FBI agents interviewed El Hage about his

connections to bin Laden and the people in Nairobi. According to prosecutors,

El Hage denied knowing Odeh and claimed to not recognize him in a picture

during this interview.

On September 15, 1998, El Hage testified before the grand jury investigation

into the Africa bombings. Here, prosecutors say, he testified that he never

heard that al-Banshiri died and that he didn't know Odeh and other people who

knew bin Laden. Several days later, El Hage was arrested and charged with

perjury. On October 7, 1998, a new indictment was returned by the grand jury,

expanding the charges against El Hage to include conspiracy to kill United

States nationals. In May, 2001, he was found guilty by a federal jury of both perjury and conspiracy.

last updated September 12, 2001

|