|

|

Who was Joachim of Fiore?

Joachim of Fiore is the most important apocalyptic thinker of the whole

medieval period, and maybe after the prophet John, the most important

apocalyptic thinker in the history of Christianity. He's born in Calabria,

some time about 1135, from what we would call a middle class family today. And

he was an official in the court of the Norman kings of Sicily when he had a

spiritual conversion, and went off on pilgrimage to the Holy Land, a mysterious

time about which we know little. When he returned to Calabria, he lived as a

hermit for a number of years before eventually joining the Cistercian Order.

... Joachim, like many 12th century monks, was fundamentally a

scriptural commentator. And he tells us that he was trying to understand and

write a commentary on the Book of Revelation, the Apocalypse, and

finding it impossible. The book was too difficult. He couldn't figure out its

symbolism. And he wrestled with this (he uses the term "wrestling" with it)

for a number of months. ... He tells us that he had been stymied and given up

the attempt to interpret the book. And then, one Easter morning, he awakened,

but he awakened as a new person, having been given a spiritual understanding

("spiritualis intelligentia" is the Latin), a spiritual understanding of the

meaning of the Book of Revelation and the concords (that is, the relationship

of all the books in the Bible). And out of that moment of insight, then,

Joachim launched into his long exposition on the Book of the Apocalypse, one of

the most important commentaries ever written.

Joachim's great insight about history is what is often called his view of the

three statuses, or three eras of history. And it's fundamentally rooted in the

Trinity. If Christians believe that God is three-fold (Father, Son, and Holy

Spirit), Joachim then said that the Bible reveals that if the Old Testament was

the time of the Father, the New Testament the time of the Son, there must be a

coming third status or era of history that is ascribed to and special to the

Holy Spirit, who gives the deep understanding of the meaning of both Old and

New Testaments. And so Joachim returned to a more optimistic view of history,

that after the crisis of the Antichrist (which he thought as imminent, as right

around the corner in his own days), there would come a new era of the Church on

earth, the contemplative utopia of the Holy Spirit, a monastic era of

contemplation. That's the heart of Joachim's great vision and contribution to

western apocalypticism.

Like Hildegard of Bingen, Joachim is a great symbolist, a

picture-thinker, in a sense. His writings, his Latin writings, are very

complex and difficult to read. I'd call them opaque, actually. But he had a

wonderful symbolic imagination. And so Joachim created figures, as he called

them. ... The Book of Figures, which goes back to his own work but was

added to by his disciples, is really the best way into Joachim's thought. So,

for instance, when we talk about the three eras or the three statuses of

history, it's very difficult to take this out of the texts themselves. But

when we have the picture of the three interlocking circles, or when we have the

image of what are called the "tree circles," where the two trees representing

the Jewish people and the Gentile people grow together through the three ages

of history, we get an immediate visual understanding of what Joachim is trying

to convey in his often obscure writings.

What is he trying to convey about the three stages?

Joachim believes that history is trinitarian, consisting of three status or

eras, as he calls them. The first status is the time of the Father, and that's

the Old Testament, lasting for 42 generations. The second status is the time

of the second person, the Son, and the time of the New Testament, also 42

generations. Joachim's calculations led him to believe that he was living at

the very end of that period, and that no more than two generations at

most--that is, no more than 60 years, and possibly less--would see the end of

the second status. The end of the second status, of course, would mark the

seventh head of the dragon, that is, the Antichrist, and Antichrist's

persecution. But for Joachim, that wasn't the end of history. A third status,

the status of the Holy Spirit, a time of contemplative ecclesiastical utopia,

was dawning. ...

Joachim's view of history was deeply organic. And this is why he loves images

of trees and flowering in order to present his message. So that there's no

clear break or definitive fissure between the first status and the second

status. The second status begins to germinate in the first. And the third

status, the monastic utopia that I talked about, is germinating in the second

status with the monastic life, beginning from Benedict, the founder of monks

in the West. And another part then, I think, of the power of Joachim's view of

history is its organic growing motif ... .

Joachim's view of the opposition between good and evil was, of course, central

to him, as it is to any apocalyptic thinker. But Joachim wasn't into what we

might call active apocalypticism, that one must take up arms against the forces

of evil. Joachim felt that God controlled history, and that good would need to

suffer, and the good would suffer indeed from the persecuting

Antichrist, but that God would be the one who would destroy Antichrist and

bring about this third status in history. So Joachim felt that the role model

of the forces of good was that of the suffering, the persecuted, not of those

who would take up arms against the beast of the apocalypse.

How did this view differ from Augustine's?

Apocalypse commentators for many centuries before Joachim had ruled out any

attempt to use the apocalypse as a prophetic book, either about the history of

the Church that was going on, or of future ages to come. That was, of course,

something that Augustine had insisted upon; that the book can't be read in that

literal fashion. Joachim broke with that, by finding in the images and symbols

of the Book of the Apocalypse the whole history of the Church: the past, the

present that he was living in, and the future to come. So he historicizes the

book, in the sense that he ties it to actual historical events. This is what

Augustine had ruled out.

What signs did Joachim see? And what was his sense of the nearness?

Joachim was a real apocalypticist in the original sense of the prophet John and

others, because he believed the current events that he saw around him,

particularly events connected with persecution of Christians, were signs of the

times, signs that had been predicted in the Book of the Apocalypse and now were

being fulfilled.

|

|  |

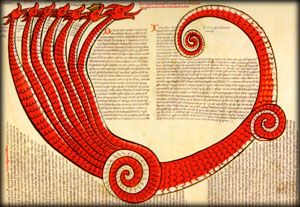

joachim's seven headed dragon

|  |  | This is what Augustine and others had ruled out, but Joachim

felt was a part of Revelation itself. A good example of Joachim's reading the

signs of the times would be his emphasis of the figure of Saladin, and

Saladin's reconquest of Jerusalem in the year 1187. When Joachim comes to

interpreting the 12th chapter of Revelation, he sees the

seven-headed dragon as indicating seven heads of concrete historical

persecutors through the course of history, and not just as a general symbol of

evil. He identifies the sixth head with Saladin--he Islamic leader who

reconquered the city of Jerusalem from the Crusaders in the year 1187--and sees

him as immediately preceding the coming seventh head, who will be the

Antichrist, the last and greatest persecutor of the second status of the

Church.

Joachim had an international reputation in the late 12th century.

We know that he functioned as what I have called an apocalyptic advisor to a

number of the popes of the 1180s and the 1190s. Despite living on a lonely

mountaintop in his monastery in Calabria, the prophet's fame had spread very

wide. And so it shouldn't surprise us that King Richard the Lion Hearted, when

he's on his way to the Third Crusade and he has to spend the winter in Sicily

(because of course you can't sail during the winter on the Mediterranean), when

he stops there in Messina, he calls for Joachim, the famous prophet, and asks

for his prophetic advice about what will happen. And Joachim travels to the

palace there in Messina, in the winter of 1190-1191. And we have the accounts

of his preaching to King Richard, and Richard's questions to him.

What would somebody like Richard the Lion Heart ask Joachim? What kind of

advice could Joachim give?

Well, Richard, like any medieval figure, did believe in prophecy. And he felt

that God did indeed send visions to certain inspired figures, and that these

visions could sometimes give one a hint, or even more than a hint, about what

was to come. Now, one of the accounts emphasizes that Joachim predicted a

victory for Richard. And we know Richard achieved at best a kind of Pyrrhic

victory. But I see no reason to doubt that Joachim prophesied something to

Richard, probably in a vague enough fashion so that if it didn't fully come out

that way, he was, in a sense, covered. ...

home ·

apocalypticism ·

book of revelation ·

antichrist ·

chronology ·

roundtable ·

primary sources ·

discussion

readings ·

video ·

glossary ·

links ·

synopsis

web site copyright WGBH educational foundation

|