Interviews: Michael Myers and Stuart Altman

They were longtime health policy advisers -- Myers on Ted Kennedy's staff and Altman advising three presidents. As they suggest here, the long political history of health care reform is, in many ways, the story of Ted Kennedy.

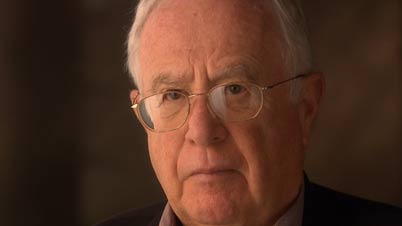

Michael Myers

He worked on Sen. Edward Kennedy's staff for 23 years as a health policy adviser. This is the edited transcript of an interview conducted on Dec. 15, 2009.

[Sen. Kennedy made a surprise appearance at the March 2009 White House forum on health care.] From what you can tell, what does he think when he looks around that room and sees the stakeholders and all the political stripes in the room?

The summit in March 2009 was really for Sen. Kennedy the culmination of years and years of labor and pushing along the health care agenda. And there he had in that room in the White House the president of the United States fully committed to the health reform that had been his vision for so long. And assembled were members of Congress, his friends, his colleagues and all the stakeholders who had been enemies to the project in the past were there, committing their support to it. So it was really a coming together in a terribly exciting way for him of a dream that he had been nurturing for so many years.

Did he believe that it actually could happen?

Yes, he did. He knew the difficulty. As he would often say to anyone who would listen, "Look, if this were easy, we would have done it a long time ago." So he knew it was hard. This is very difficult work and difficult votes to be cast. But it seemed that this was a moment that the stars were aligned with the president, with the Congress, with the business community, with -- the American people are really ready for change when it comes to health care.

How sick was he at that moment?

He was still going through chemo, so there were good days and bad days. But on that day I think he felt the moment, and the juices were flowing, and there was nothing that was going to keep him from going to the White House on that March day.

Were you there?

Yes, I was.

What was it like to see Karen Ignagni stand up representing AHIP [America's Health Insurance Plans] and say there were some things they were going to cooperate on?

There were many there who had been on opposite sides in the past -- not just the insurance industry, but elements of business, even the doctors; some of the doctors in the past have opposed our efforts. So just seeing all those people convened by the president of the United States saying, "Let's get this done," that was a very emotional moment.

And did you believe that it was more than just a symbol and more than just a kind of iconic photo op?

When people are there with the president and with members of Congress and with Sen. Kennedy, who was seen as the leader and the real symbol of the effort, I don't think it's just symbolism. It really did galvanize a whole host of people to put down the different burdens of the past and to move forward for the common good.

... What stars had aligned to bring [industry leaders and lobbyists] to the table at this moment?

For the March summit there was a lot of groundwork laid in advance, a lot of conversations, meetings leading up to that moment. So there were no real surprises at the summit itself.

I guess the real surprise was people weren't sure whether Sen. Kennedy was going to be there. And it was really a moment when he walked into that room, and so many didn't even realize he was in town that day. It was a magic moment.

What is Big Pharma worried about, and what do they want to get out of what's going to happen over the summer?

Unlike in the past, the different industries involved -- pharmaceutical industry, insurance industry, hospitals -- realized that the health care system really is desperate; that there is a yearning not only by the American people but by our business community to overhaul our health care, to help us be more competitive in this global economy. So I think they felt the pressure to join the effort rather than to fight it this time. And that has made all the difference.

Why did Sen. Kennedy endorse Obama?

I remember Sen. Kennedy appearing on Meet the Press with Tim Russert, and this was before Sen. Kennedy had decided whom to endorse, and he was asked, "What are you looking for in a candidate?" And he said, "I'm looking for someone who can inspire." So that was his litmus test.

As we went into the primary season and he saw Sen. Obama -- candidate Obama -- on the campaign trail, saw his speech after the Iowa caucuses, saw in him someone who can inspire the country to bring about real change at home and abroad, and he felt that Barack Obama was that person.

How important was health care in that equation?

Very important. I think on the domestic agenda, that was number one on Sen. Kennedy's mind. And he and candidate Obama discussed that frequently before the campaign even began, and Sen. Kennedy endorsing him was a strong nudge that health care should be front and center for the new administration.

Strong nudge or implicit promise?

I don't know.

Kennedy's power to handle the bipartisan element of any complicated piece of legislation -- talk a little bit about the way he would bring people over to his side.

Sen. Kennedy was a people person. He loved people, and he could sense what was on their minds as he was conversing with them, a real master psychologist in a way. And that helped him in reaching across the aisle. He would know what his Republican colleagues were thinking. He was able to touch them in ways that few legislators could. And they knew that he would keep his promise. If he said, "We've got a deal," they had a deal, and he would not break it, and he would fight as hard as he could to make that deal become a reality.

You would have been around during the Clinton administration effort in the early '90s. What happened to that?

There are a lot of different ideas or theories about what happened to it. One, it became far too complicated.

Number two, it took so long that the opponents were able to organize a very effective "Harry and Louise"-style campaign against it. These complicated pieces of legislation, while they're popular when they begin, the congressional sausage -- there's an unattractive period that you have to go through to get it done. And if that period takes too long, then the legislation loses altitude. And I think that's what happened in '93 and '94.

Was Sen. Kennedy hopeful at the beginning of the process that the Clinton plan might actually happen?

Sen. Kennedy was very hopeful. And to the end he said that the components of it was a very good bill. It's just that there was too much weight to carry across the finish line in that period.

Did Kennedy offer advice and suggestions to Obama and his team about how this go-around could be different than the way that it was in the Clinton administration?

There were at least two pieces of advice that I remember Sen. Kennedy offered the Obama administration. One is to move very early. Don't waste any time; let's get moving quickly. Number two, he said we should all work from one bill. There are five committees in Congress, but we should all work from one bill. And he said that to his colleagues in Congress as well.

And that's pretty much what has happened, that the different committees may have differences in nuance, and certain policies are different, but all five committees in Congress really operated from the same architecture, and that's a remarkable, remarkable thing.

The advice and impulse to get going pretty fast on health reform is happening at the same time the economy is really bumpy. [Head of the President's Economic Council Lawrence] Summers and [Secretary of the Treasury Timothy] Geithner are saying: "Wait. Push it down the road a little bit. Let's deal, Mr. President, with the economy." Was Kennedy involved in keeping the president's feet to the fire on health care?

Sen. Kennedy never had any doubt about the president's commitment to health care. Every time they talked, the president reiterated that commitment. I know that the president's advisers were debating the issue and how to approach it, given the sad state of the economy, but the president himself was never in doubt.

What is the importance of [former Sen.] Tom Daschle [D-S.D.] in the early-going through the campaign and also his appointment as both what we called the health care czar inside the West Wing and also at HHS [Health and Human Services]?

Tom Daschle is universally admired and respected, so having him with the president, talking health care through the campaign and in the early days of the administration, was an enormous signal that this really is a priority for the administration. They're not messing around. They're bringing in the pros; they're bringing in the big guys to get this done.

So it was a setback when Sen. Daschle was not [appointed] the secretary of health and we had to wait to fill that position; was not [appointed] the health czar in the White House, had to wait and fill that position. It did mean that we didn't move quite as fast as we would have otherwise, as the administration got its personnel together. But Sen. Daschle remains someone who's consulted by members of Congress on what we should be doing next, how we pull this together. And I'm sure the president and others value his advice as well.

But the loss of Daschle matters?

Well, this health reform is bigger than any one person. It's bigger than Sen. Kennedy; it's even bigger than the president. So it's something the American people want. It's something that's going to happen no matter who's on the personnel roster at a particular moment.

Daschle falls; Sen. Kennedy is ill. Is his illness affecting anything that's happening at the White House during January, February and March?

No, Sen. Kennedy was in constant touch with the White House, with his colleagues in Congress about the health care effort either in person or by telephone.

So can you help me with some of the players? Who's [Sen.] Max Baucus [D-Mont.]? Where does he come from, and what is his expertise on the health care issue, and what role [do] Sen. Kennedy and you play in helping him?

There are two committees in the Senate with jurisdiction over health care issues: the Health Committee and the Finance Committee. So one of the challenges of the past was jurisdictional disputes between strong committee chairmen, and that was one of the issues we faced in 1993 when Sen. [Daniel Patrick] Moynihan [D-N.Y.] was chairman of the Finance Committee and had his own views about how we should proceed on the health care issue in the Clinton administration.

So it was really important for Sen. Kennedy and Sen. Baucus to be of one mind on this health care effort. They talked often early on in this project about how they were going to get this done. They had lunch together at Sen. Kennedy's home in Washington to discuss it. They spent two or three hours that day just mapping out the whole project.

And so that was an exciting thing for Sen. Kennedy, that here we had the chairman of the powerful Finance Committee who was saying not that we should wait, not that we should do it a different way, but we should get it done, and let's work from President Obama's plan and get this done. That was enormously encouraging, and a very significant marriage between Kennedy and Baucus.

But would all of this have been different if Sen. Kennedy had not been ill? Would it have always had to run through Sen. Baucus? Would things be different in that sense?

A lot of things would be different, I think. But Chairman Baucus is an important figure in this debate, and his committee has important jurisdiction over this debate. So no matter what, Sen. Baucus was going to be, and is, a major player in the health debate and will get a lot of credit for getting it done.

How would it have been different?

People ask me all the time how would it have been different if Sen. Kennedy were here and healthy throughout that debate. I think the bill would be done by now, for one thing. I think he had the ability to put together a plan and to rally his colleagues in a way that I haven't seen with any other senator during my time in the United States Senate.

And so he would have pushed things along. He would have encouraged his colleagues; he would have prodded his colleagues; he would have yelled at his colleagues to get this done and get it done in a timely way. So I think maybe the bill would be the same as what we see right now, but we would have gotten there more quickly with Sen. Kennedy present in the Senate.

Are there some specific things that wouldn't have happened or would have happened that haven't happened?

There have been moments in this debate in which Democrats were unsure of the strategy for victory, and that's where Sen. Kennedy excelled, in providing his colleagues with a vision of the path forward.

The Democratic Caucus meets every Tuesday. They lunch together, and all the Democrats in the Senate discuss what's on the agenda and how we're going to approach it and who's going to vote which way. And those moments were magical ones for Sen. Kennedy, because he could go into that room and stand up and provide a clear plan for how Democrats should move forward on a particular issue. And I think that's been missed in this debate. There hasn't always been a clear plan.

[Why wasn't a single-payer plan on the agenda?]

Sen. Kennedy was a strong proponent of a single-payer approach to health care; he introduced Medicare for All. But the votes were just not there. America was just not ready for that approach. So he was very practical about it and sought other ways of accomplishing the goal of improving the quality of health care for all Americans and making sure all Americans were insured.

There was a moment where protesters stand up in the Finance Committee hearing and are arrested and taken out. They're very unhappy. I've talked to some of those people, and they say, "Sen. Kennedy let us come and speak at the Health Committee hearings; Baucus wouldn't let us in; the White House wouldn't invite us to the March 6, 2009, event." Why not?

Sen. Kennedy always felt that it was important for all views to be heard and that those views should be respected. So when we were having even staff-level meetings with interest groups, with those who had ideas about health reform, it was important to us as Sen. Kennedy's representatives to allow those views to be heard.

And I remember once we had about 200 people in the room, and some were from the right; some were from the left. And the single-payer crowd was there, ready to protest the meeting, and we invited them up to the mic to present their view. And it just infected the whole room, that yeah, this was a place where we all come together and present our ideas and that we're all committed to health reform. We may have different ways of getting there, but we're in common cause on this together.

So why didn't Chairman Baucus do that?

I don't know.

Did the senator know about the so-called PhRMA deal when it was going on? If he knew about it, what did he think about the deal?

The White House and the Finance Committee were involved in that. It didn't affect Sen. Kennedy's committee, so he was not involved in that.

Did he ever talk to you about it or what he thought about it? Did it surprise him that a deal like that was done? Everybody tells me the guy was a real realist about all of this stuff.

Sen. Kennedy was a person of great, high ideals. He had real principle, and he never deviated from that. But he was very practical about the different ways of achieving those goals, and if it meant having an agreement with the devil in order to get there, he would consider that, even if it included an agreement with the pharmaceutical industry. So, as long as the goal of providing quality, affordable health care for all Americans is met, then all the agreements you have to make along the way are well worth it.

What do you think of the White House's role in May, June, July? This is not a Bush White House where they mandate and they go right by Congress. And it's not even a Clinton White House where they send up a bill. This is a legislative presidency. The Obama administration have laid out a plan, and away they went. But it wasn't a specific plan. The line moved back and forth a lot. What about the White House's role in those months?

Over the summer months, I think it was important that the White House allow Congress to do its work. The president had laid out a framework earlier in the year, and we were operating within that framework. But I think the strategy was correct to allow Congress to have a say over what goes within that framework and for the White House not to be dictating line by line what should go into that legislation. That's just impractical. But it also meant that there's more congressional ownership of the process.

Now that we're in the tough slogging, where this is the hard deals being made, the tough agreements, there has been created this mood within Congress, this strong investment in the product, and if that had not happened over the summer, I would be willing to wager that there would be a lot of members of Congress who'd be walking away right now.

And at some moment the White House says: "It has to be done by August. We want this done by August." It slows down. Why?

It slows down because this is really hard. This is some of the toughest legislation that you'll face as a member of Congress. It affects every single one of your constituents -- not just a few, every one of them. So it's really tough legislation. We all wish that we could have gotten this done by August. We thought the president was right, that leaving this hanging out there over August would be harmful; it would be a setback. And it was. We saw the town hall meetings and all of that going on over August, and those were tough times. And it would have been better to have avoided all that if we could.

This notion of bipartisanship [that] the president was very big on -- Sen. Baucus, the "Gang of Six," a lot of effort and time spent courting and dealing with those people -- from your perspective and the senator's perspective, did it seem like folly? ...

We all hoped and thought that this would be a bipartisan bill, but it became clear fairly soon after the election that the Republican game plan was going to be just to say no, to deny this president any victories. And that has played out on the economic agenda, and it has played out on the health care agenda. We all tried for months and months and months to see if there were some Republicans who might want to join us. And in the end, there may be; I haven't given up hope even yet. But the Republican game plan was very clear starting in January.

In summer, was Sen. Kennedy able to call Sen. [Chuck] Grassley [R-Iowa] and others and say, "What's it going to take?"

He was calling people every day all through the summer and the spring as well. And when he was here in town, he would meet with people, some of the Republicans with whom he's worked in the past, to try to prod them along and cajole them and do whatever he could. But the orders had come down from on high in the Republican Party that they should not cooperate on the Obama health plan, and they were sticking to it.

Was the senator distressed by that?

Yes, because this was an important moment for the country. It's far better with Democrats and Republicans united and getting it done, but if we have to do it without Republican help, we have to do it. The country needs it, and we're not going to shy away from the project just because Democrats have to do the heavy lifting alone.

What did he say about the sense that it was slipping away? I understand he didn't believe it was really slipping away, but that it was now going to be a real slog, the heading into August?

Sen. Kennedy had a real feel for the chemistry of the Senate, the chemistry of the institution. And in the days when he could not be physically present in the Senate and he would call me several times a day, he would ask, "What's going on?" But more than anything else, he would say, "What are people saying? What are people thinking? What are they saying in the cloakroom? What's the atmosphere?," because that kind of information told him what the psychology was at the moment and what was possible. So it did worry him that this was taking longer than expected.

How would you answer that question?

Well, it would change from day to day depending on whether Democrats had just had a victory or they were pushing through on something else. It was more a mood of being able to tell him that members of his committee were excited that they were the first of the five congressional committees to produce legislation and what an invigorating moment that was, not only for his committee members, but for all Democrats in the Senate, that a committee got it done after a tough markup. And that was a thrill to him, that his committee was the first.

So he wanted to know what people were saying, what people were thinking about that, what people were saying in the cloakroom about President Obama, what they were feeling about the leadership from the White House. Those were the kinds of questions he would ask me day after day as he kept tabs on the Senate. He wanted to know it all.

Did he feel it slipping away?

No. He was always confident that it would get done and felt that, by the summer, Congress was so deep into it, so invested into it, all the committees were fully engaged on it, which had never happened before, he felt we had crossed a point of no return, that we would get this done.

So when the craziness happens in August 2009, what is he thinking? Did he anticipate it himself?

Sen. Kennedy was concerned about what August would bring. We were all concerned about that and really, really wanted, if we could, to try to get this done before August. We didn't, but we survived it, and I think a lot of that was because members of Congress were already deeply invested in the project. And despite the trials and tribulations of August, they came back determined to get this done.

In the midst of all of that there are people who say to us, "The White House looks like it's lost control of the debate, control of the agenda, control of the problem." Your sense?

Whenever we reach tough times in a legislative battle, there's a lot of finger pointing. I don't pay attention to a lot of that. I don't think Sen. Kennedy did either. He stayed focused on the mission, and that was to get the health care bill done. And if we had to work on a particular member of Congress to give a jolt of enthusiasm to him, he was willing to make that phone call. If he needed to compare notes with the president, he would do that as well.

The inevitable happens vis-à-vis one of the stakeholders, the insurance companies. Sometime in July, holding them at the table becomes harder and harder. There's angry words back and forth between them and the White House. Surprise to you?

The overall strategy on health care was -- and it was one of the lessons from '93 and '94 -- we should not wage a multi-front war. In '93 and '94, we battled the insurance industry; we battled the business community; we battled the hospitals; we battled the doctors; we battled the pharmaceutical industry. So there were battles all over the place that we were waging. We felt the American people were on our side, but in the inside-Washington game, you also have that battle going on as well. So it was important as part of our strategy early on to minimize the number of those battles.

So if we could do a few things here and there that would bring along the support of particular industries, or at least have them sit on their hands through this debate, it was well worth it. And so we pretty well reduced this to a one-front war, where the opponent to the health care bill is the insurance industry. And that's fine. That's fine with members of Congress, that's fine with the White House that that would be our battle, and we [would] really focus on that one obstacle as we get health care reform done for the American people.

You knew it would be them anyway?

Yes.

The senator dies. How do you get the word?

Those of us who were close to him knew that this time was coming in August. And I got a phone call from another member of our staff that he had passed late that evening with his family around him, at his home that he loved in Cape Cod.

We've talked to so many people who say in the midst of all that chaos out there in those town meetings and the tea parties and the death panels, for the senator to pass away is in a way a cease-fire moment, a lot of people leaning back and saying, especially Republicans in the Senate and his friends on the other side of the aisle, "Let's think about this for just a second." Was there a sense in your mind, in your heart, that that was going to be one of the side effects of the senator's death?

I don't know. I think those of us who were close to him, and I certainly was, had our own grieving going on at that moment, and we weren't concentrating so much on the larger national picture. But I certainly heard so many say, "We've got to get this done for Sen. Kennedy." And I think it did cause so many around the country and in our government to redouble their efforts to really get it done.

The president reacts to what is happening in August and what is happening with the insurance industry by pulling maybe his most potent weapon, which is an appearance before the joint session of Congress. Was the White House staff asking for you guys to help them?

The president can handle that very well himself, and there are certain milestones or events in the course of this legislation that will always be remembered: There's the summit in March; there are the markups over the summer, but certainly the president's speech in a joint session of Congress in September. After the chaos of August, there's people in Congress trying to regain their moorings. The moment was just the right moment; the words that he uttered were just the right words. And Democrats came out of that session feeling energized with a new focus on it. It was palpable. It was palpable.

And the effect of [Rep.] Joe Wilson's [R-S.C.] "You lie, you lie," outburst?

I was in the chamber when the speech was being given, and there was a gasp, but on both sides of the aisle, over that. But that's just one of those things, and I think everybody just moved on after the Joe Wilson comments, and we just all redoubled our efforts to get the health care bill done.

Somebody told us that it was really too bad that it had happened, because his speech was so important, but the press being the press concentrated for the next three days on Joe Wilson. Your thoughts?

That may have been the effect on the American people, that the Joe Wilson comment may have overshadowed the message that the president had. But in the chamber that night, there was a real effect on the members of Congress, notwithstanding the Joe Wilson comment. And [the speech] had the effect I think the president intended. The audience was the men and women right there in that room.

The president reads from Sen. Kennedy's letter, basically deathbed letter. How did that feel?

I felt very proud. I think all of us who were associated with Sen. Kennedy felt very proud at that moment that he had come up with the words that the president of the United States felt were so significant, so motivating, that they deserved to be read before the entire Congress, and really before the entire nation. And it got to really the heart of what this enterprise is about. It's about our character as a nation, and I'd heard Sen. Kennedy say that privately so many times. But this was really the first time that I can remember that he wrote the words down and sent them to the president of the United States, that this is about our character as a nation and how we care about our fellow citizens.

One person who'd been with Sen. Kennedy all the way back to the '70s Nixon/[Rep. Wilbur] Mills [D-Ark.] health care bill said, "You know, the senator always regretted not having supported that." Did he ever say that to you?

Yes. Sen. Kennedy, over the 20-plus years that I worked for him, would always say, "Let's accomplish what we can, lay a foundation and build on it." And he said to me often, "You know, old President Nixon came up with a health care plan that in retrospect looks pretty good, so one of my regrets as a senator is that I didn't support the Nixon plan and make it happen," because it provided health care for all Americans.

So I think looking at this moment and this legislation, it isn't what everyone wants, but it's a very good bill. It provides coverage for all Americans; it keeps a thumb on the insurance industry, on premiums and the quality of coverage. There's a lot of good in this bill. And it's such a big enterprise that there's no doubt in my mind, and I know there was no doubt in Sen. Kennedy's mind, that we would be building on this accomplishment for years and generations to come, just as we've built on Social Security, built on Medicare and so forth. The same will happen with this health care bill.

So for Americans who say, "Wait a minute. Barack Obama promised me that he was going to be a transformative president, that something really different was going to happen. And then I sit here and watch Billy Tauzin and PhRMA get a deal, and I watch them sit at tables and just bargain away everything, I watch the public option disappear. What am I actually going to get out of this?," is this it, or is this the way Washington works, and it's just time for the American people to get real?

As Sen. Kennedy said over and over to anyone who would listen, if this were easy, we would have done it a long time ago. He had the scars from previous battles on health care, and he would be very proud of the foundation that we're laying now, a transformative foundation for American health care. And what people will get out of it is they'll get quality, affordable health insurance. Every American will have that now. And that the bill puts strong controls on the insurance industry to make sure the premiums don't go through the roof, to make sure they're banning their practice of denying people insurance because they have pre-existing conditions, all of that will be gone.

That is huge. That's a major accomplishment for the American people that we can all be proud of.

Stuart Altman

Altman was a health policy adviser to three presidents: Richard Nixon, Bill Clinton and then-candidate Barack Obama in the 2008 presidential campaign. He talks about the surprising moment during the early 1970s when Ted Kennedy launched secret negotiations with Richard Nixon and House Ways and Means Chairman Wilbur Mills, to see if a national health insurance plan could be passed. This is the edited transcript of an interview conducted on Nov. 13, 2009.

What do you think drove Richard Nixon to consider health care reform when he was president?

That turns out to be one of the issues that has perplexed me. Here was a conservative Republican president who really pushed hard for a plan that, at any level, if you looked at it in today's context, would be considered very liberal.

My best sense of why was that he was very much afraid of Ted Kennedy. And you have to appreciate the fact that Nixon was elected in the late 1960s right after we had passed Medicare, and the country was still caught up in a belief that government should be a major player in health care. ... And Nixon did not want to be viewed as sort of behind-the-scenes, or giving any ground to the liberal arm of the Democratic Party.

So, it was, I think, a political call. Some also suggest that, because of certain situations in his own childhood and family, he appreciate the issues of not having good coverage. But I think it was mostly political. …

So what were the basic elements of the Nixon plan?

It went through two iterations. The first one, which was in the late 1960s/early 1970s, basically built on a private insurance system. It had significant benefit expansion. But the benefits themselves were quite limited, compared to what a good health insurance policy called for. But, most importantly, it called for what we call an employer mandate, where every employer had to provide coverage.

It was criticized in the beginning as being an inadequate plan. And, after all, this plan was compared to the plan that Sen. Kennedy was advocating, which was a total comprehensive plan, totally run by the government, a so-called single-payer system.

So in 1972, Nixon directed then-Secretary [Caspar] Weinberger, who took over [the Dept. of Health, Education and Welfare [HEW]] from Eliot Richardson, to design a more comprehensive plan. And that was the plan that my office put together, which turned out, was very comprehensive, in terms of benefits. It required an employers to not only provide it, but pay for substantial amount. It expanded what we now know of as Medicaid. And it would have covered every American.

[What was the Kennedy-Mills plan?] What did Mills bring to the table?

Okay, let's back up just a second. Not only did Sen. Kennedy and the Committee of 100 have a single-payer [plan] and President Nixon had [a plan], but every organization, including the American Medical Association [had a plan].

If you remember, the American Medical Association fought as hard as it could against Medicare. It really didn't want it to be passed. But it learned that, by [it passing], it separated the American doctor from the populace. And all of a sudden, people began to question their doctor on whether they really were concerned about the health of the population, or just their own pocketbook. …

And while, if you picked up the newspaper, whether it was The New York Times, or The Wall Street Journal -- didn't matter -- all of them were saying we were going to pay something.

Kennedy began to be convinced that his single-payer approach was not going to work. So then you switch. And here was the most powerful member of the Congress, [Rep.] Wilbur Mills (D-Ark.), who had been the orchestrator of Medicare, was the Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, which was the most powerful committee in the Congress. …

Mills himself began to think about maybe he could run for president. And, at that point, Ted Kennedy was quite young. And, there was some talk about maybe Kennedy would run for president and Mills would be his vice president. There were all these political discussions. And so they linked together to talk about health reform, to see if they could come up with something.

Initially they didn't come up with anything.

But then Nixon proposed, in early 1972, this comprehensive plan called CHIP, Comprehensive Health Insurance Plan, Kennedy and Mills said, "OK, we will take your concept and build on it. It won't be a traditional single-payer. It'll include insurance companies, but it will have a payroll tax funded."

And so it was still much more government than Nixon wanted, but built very much on the Nixon approach. And so that became known as the Kennedy-Mills bill.

So, when you bump into [Kennedy aide] Stan Jones in Albuquerque, where did things stand?

I think we had had a very preliminary meeting. What I found out later was that Sen. Kennedy instructed Stan Jones to contact me, to see if there was something that could actually bring, not only Kennedy and Mills together, but Kennedy, Mills and Nixon together. ...

And so, when we came back down, we arranged to have these secret meetings in the basement of an Episcopal church that is just north of the Capitol. And, we met in the pub of this church. It included Stan Jones representing Sen. Kennedy, Bill Fullerton, who was the representative of Mills, myself and two others from HEW, representing Weinberger and Nixon. And we met several times.

Why secret?

The unions were furious at Sen. Kennedy for even suggesting a role for private insurance industry. Second, in the Kennedy/Mills bill, there were more deductibles and co-insurance, which the unions fought. So, he was under a lot of pressure from the left not to have anything to do with this. But he went ahead anyway, so he wanted to keep it secret.

And I think it's fair to say that Nixon and Weinberger were not too happy to have it be known that they were talking to Sen. Kennedy and his staff. So for all our sakes, secret was important.

Were you surprised that Sen. Kennedy would be interested in laying down with the lion?

I was a 32, 33 year old, all caught up in the times. And I was super-optimistic that we were going to do something. And things were moving so quickly. There was so much going on that, quite frankly, nothing surprised me. I just took it all in stride. And I was caught up in the euphoria of the day, that we were going to reach a compromise. And so while historians and others may look back and be shocked that this happened, I was just out there, "We're going to get it done." …

The negativism that we have today, in 2009, really didn't exist. We did not have the ultra-right really attacking this. And, while the doctors and hospitals were nervous about what this might look like, they were not going to be opposed. It turns out that Medicare was a wonderful thing for them. Doctors had their bills paid. Hospitals had their bills paid. And a lot of the opposition to government involvement had been muted, if not eliminated. So yes, there was tremendous optimism. …

So what happened?

What happened? Well, unfortunately, not politics so much as personal situations developed. First of all, President Nixon was very much involved in the Watergate situation. …

As we began to discuss these issues in the church, and we would try to come up with compromises, and then we would take them back to our constituent groups, it was clear that Sen. Kennedy felt he could not go any further in compromise with Nixon. And on the same token, Nixon felt pretty much out there, way beyond his advisers. And he and Secretary Weinberger were not willing to go any further. And so the Nixon/Kennedy/Mills triumvir fell apart. …

What did we lose?

… I've been doing this, now, for almost 40 years, and there was no better time to get it done than the early 1970s. All the stars were aligned. And since that time, it has gotten increasingly harder, on a variety of fronts. The whole situation has gotten more complicated. The politics of the left and the right have hardened. And you see what's happening here in 2009 and 2010, how difficult it is to get anything done.

The power of the lobby, I'm not just talking about dollars and cents in campaign finance terms. But it strikes me as a very different world in Washington, with PhRMA [Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America] and AHIP [America's Health Insurance Plans] and all of them, and their levels of expertise and the way they fan out, and the way they appear in congressmen and senators' offices, the way they have their own studies, the way that it's all maneuvered. It seems very different. Is it?

Yes, it is. It's very different. And, perhaps, it's people like me that are most responsible for it, in that if you go back to the early 1970s, you could count on maybe both hands, and maybe a few of your toes, the key staffers who were involved in health care. The Congress had just a few. We at HEW had a dozen or half a dozen. There were a few others. The organizations, the insurance and the hospitals had some. But it was a fairly small group of people.

Now the analysts number in the hundreds, if not the thousands. And, every organization, every advocacy group has hoards of analysts presenting position papers and arguing why this won't work and that won't work. So that's part of it.

Also, the amount of money that's involved, I mean, it's hard to imagine. We were spending, in 1971, $75 billion dollars, which amounted to 7.5 percent of our GDP. Today we're at $2.5 trillion. It's over 17 percent. The numbers are staggering. But you have to understand the number of jobs that go with $2.5 trillion dollars. So the level of activity around the country that is of concern to what goes on is far greater.

And then, finally, I think the ideology is much harder today. I mean, we've always had a group of Americans that really distrusted their government and wanted to see a smaller government. But now the level of civility is totally gone. So it's not all the lobbyists in health care. It's far greater than that.

In the years between the end of Nixon/Mills and now, there are efforts, of course. Kennedy evolves into -- if he wasn't already -- a true pragmatic instrumentalist, for lack of a more precise term.

Absolutely. …