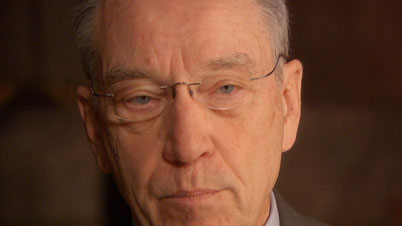

Interview: Sen. Chuck Grassley

- HIGHLIGHTS

- What went wrong with the bipartisan effort?

- His conversations with the president

- The "ethically wrong" deals with lobbyists

- The angry town hall meetings during the August recess

The ranking Republican on the Senate Finance Committee, Sen. Grassley (R-Iowa) was an important swing-vote in Obama's bipartisan strategy for getting a health reform bill passed. This is the edited transcript of an interview conducted on Feb. 25, 2010.

[You were at the] March 5 summit meeting [at the White House]. … Obama comes into Washington saying he's going to change the way Washington is done. ... Do you think in some ways that this is going to be harder than maybe President Obama imagines?

I was thinking of President Obama at that particular time, things he said during the campaign, and most of it was said because he wanted to have a position different than Sen. [Hillary] Clinton, his opponent in the primary. And at that particular time, he was saying: "We don't want an individual mandate. We want to do this more incrementally. We don't want to have federal government take over health care." That was kind of the environment, I felt, that he was in at the time of the March 5 meeting.

And of course then, after the election, not from the president, but from people in the extreme left of his party, came the idea of a public option. So at this meeting, I thought that was the most difference between the president and me, or between Republicans and Democrats, and maybe even between, at that point, between Democrats and the president, because the president was not for a public option during the campaign.

And so that's what I brought up at that meeting, and I don't exactly how I expressed it, but I expressed very much concern that that was something that could divide us, and for him to take a strong look at that and maybe know that [there were] people like me, and we wanted to work for reform, but we didn't want government taking over everything.

... How difficult did you see the job?

At that point, I wouldn't compare what I was thinking with what the president was thinking, because I've had this 10-year working relationship with Sen. [Max] Baucus [D-Mont.] -- six years I'm chairman [of the Senate Finance Committee]; four years now he's chairman -- and we've always started with a blank sheet of paper and built something from the foundation up. So I wasn't worried about this little piece or that little piece at that point. It was a case of getting a consensus.

The president had been talking about ... the need for bipartisanship, that they were going to work very hard to get bipartisanship. What did he do wrong to make that impossible?

At that point, at the beginning, I wouldn't want to say he did anything wrong. ... I looked at this as something I'm a member of, an independent branch of government. I'm the policy-maker; I'm the lawmaker. I think that less presidential interference the better. ... I was a member of the minority. I was working with Sen. Baucus in a way that we'd always worked, starting with a blank sheet of paper.

And, by the way, from January through September, Sen. Baucus and I were still working on what we thought ought to be not just a bipartisan bill but a kind of a consensus bill -- in other words, something that would get 75 or 80 votes. That was his point of view; that was my point of view. That's generally what we had done. We were not thinking in terms of just getting a product that would maybe get barely 60 votes, ... and particularly because this was reforming one-sixth of the economy, that it was so dramatic of a change that it ought to have a bipartisan consensus along the lines of what a lot of social change in this country has been, bipartisan: Social Security, civil rights, Medicare, Medicaid. Maybe you can name a lot of others, but they've all had broad bipartisan support.

So what went wrong?

... I think what went wrong was the impatience of the White House or Sen. [Harry] Reid [D-Nev., Senate majority leader] -- or maybe I'm not right in using the word "impatience," but maybe the extreme, the great push they got from the left wing of the Democrat Party, to do extreme policy change. They were impatient with Sen. Baucus and Sen. Grassley and the "Group of Six," trying to work toward bipartisanship. And Sept. 15 comes, and I think they just decide, "We're going to just go the partisan direction."

And I think Sen. Baucus at that point did not have any choice, because he was getting so much pressure from the left wing of his party to move on. And from my standpoint, I look back now at hundreds of hours, through 31 meetings of the Group of Six, and never once was there a harsh word expressed among the six; never once did anybody walk away from the table. And roughly in the middle of September we were still at the table, and somebody decided that they needed to walk away from the table, and it wasn't the three Republicans.

... Take us back to the moment of why the Group of Six was formed.

I wouldn't want to say that there was one time that a decision of a Group of Six was formed, but for the months of January, February and March, maybe into April, Sen. Baucus and I would have regular meetings, and of course during that period of time we also had what we called roundtables; we had some hearings. Massive amount of work went into this, even before the Group of Six met.

And I think it was a case of both of us feeling that we needed people that represented broad interests of our respective parties to sit down and see what could be done. I was very comfortable with it. I think he was very comfortable with it. If you're asking me exactly when that decision was made, I could not reflect on it. It was just kind of something that we worked our way into, I would say.

... You also sat down with the administration. Did Obama to some extent court you as well? Did he try to work specifically with you? And how did he try to bring you onboard?

... Any contacts that the president had with me -- maybe once or twice, at most three times, by telephone, one time at that March meeting that you mentioned; another time Sen. Baucus and I had lunch with President Obama and Vice President [Joe] Biden. But there was not in-depth policy discussions at those meetings. Well, I guess you would say there was policy discussions, but not the sort of a thing where you get down to crossing the Ts and dotting the Is, in that sense.

And then we had the final one that I remember was roughly Aug. 5 or 6, where the six of us went down to the White House. Again, it didn't get into a lot of detail, but I still remember that August meeting better than any other meeting, because the president pointedly asked me would I be comfortable being one, two or three Republicans voting with the Democrats for a bipartisan thing. And I asked him, "Well, it would make it a lot easier to get a bipartisan bill if you'd just say -- you don't have to say you're against the public option, if you'd just say you'd sign a bill that didn't have a public option in it."

He didn't give me an answer one way or the other on the point I asked, and this is the answer that I gave him. I said -- and Sen. Baucus was sitting here, and later I asked Sen. Baucus to confirm what I said -- I said to the president: "That's not bipartisanship. Sen. Baucus and I started out months ago with getting a broad-based consensus, maybe 75 or 80 votes. So three Republicans voting with the Democrats, not bipartisan as far as I'm concerned."

And then I get into this stuff about, you know, one-sixth of the economy, get into this bit about health care affecting every American, and it ought to be done on a consensus basis like other social changes that have been brought. And that was kind of the end of that conversation.

Now, the meeting went on for about 45 minutes or an hour, and a lot of things were discussed, but that's really the only thing that the president and I discussed one on one, in a sense.

It's been reported that that was a real turning point, that the Democrats to some extent gave up on the Republicans at that point. Do you see that?

I did not see it out of that meeting, ... because the next week we started a monthlong August break. We still had teleconferences of the Group of Six and appropriate staff, and then we still had meetings during the week or two after Labor Day.

I think the turning point came mid-September. And all I can say is, I don't know what that turning point was, because we were still at the table, but they decided to go ahead in a partisan way.

Again, I think it was a response, not because Sen. Baucus thought it ought to go that direction, although you'd have to ask him. I think it's more of a case of them being pushed by the extreme of their party to respond to their base that thought: "We've got to move ahead. We've got a short chance to get these extreme things we want to do. Get them done." And they were kind of forgetting that the grassroots of America was turning against the bill at that particular time, and I think they thought that they needed to hurry up and get it done before there was too much change in public opinion.

... [Critics were] looking at Congress, looking at the Finance Committee, and saying there's too much influence by the industry. People were talking about Baucus, for instance, getting $2.5 million in donations, the revolving door, that former staff went either direction -- some from the lobbyists that were now working with the committee, some people that used to be in high positions and go to industry. Does this situation with the industry influence compromise the way things worked? Did it compromise Baucus, for instance, in what was being accomplished?

I don't believe so. In fact, I emphatically say that I've known Sen. Baucus and worked with him for a long period of time. He's willing to look at anything just as policy, as I'm willing to look at things as policy.

But I can say this: that between the White House and Democrat members, there was -- you can look at PhRMA [Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America lobbying group], the deal they made with the White House; you can look at the American Hospital Association, the deal they made with the White House. There was probably other groups like that, but those are the two most prominent.

In a sense, they made a deal that we're going to contribute X number of dollars to this effort to get a bill passed. I mean, they were going to put money in the pot to offset the cost of universal care as an example. And they promised that they wouldn't stir up the grassroots. They promised that they would be at the table, be cooperating, help to get a bill passed. I look at interest groups like that, that say that they're not going to tell their members what's going on back at the grassroots of America, as economic parasites in the sense that they're getting paid to represent their interest, they're getting paid to feed back to the grassroots what they're doing. But they made a deal to keep their mouth shut, and they weren't representing their grassroots enrollees in this effort.

I want to make very clear that those negotiations that went on, the three Republican members of the Group of Six were not in on those. At least I was not in on those. I was in on the policy-making; in other words, the coverage issues, the delivery issues, the issues of covering the uninsured, changing the practice or helping innovate for better practice of medicine delivery, that sort of thing.

And the reason I didn't participate in those -- I'm not sure I was invited to participate in them -- but I do not like lobbyists who do not represent their interests making a deal in town to keep their mouth shut when they're paid to keep their members fully informed. And that's what they made a deal with the White House, to do that. And I think that is ethically wrong.

As far as the influence of the industry and just campaign money to members, is there a problem there?

I can only answer for Chuck Grassley; I can't answer for anybody else. And there's two rules I have for campaign contributions. Number one, is it legal? And number two, are there any strings attached? If it's not legal, I don't want to take it, like taking money from a foreign citizen. And if somebody is asking me that they'll contribute to me if I'll do such and such, I'm not going to take the money.

I think I have a record -- through my FDA [Food and Drug Administration] investigations taking on the pharmaceutical companies, just as an example. I took on the AARP with one of their finance, or with one of their insurance interests, as evidence of that.

... One of the allegations against you ... is people would say the Republican leadership came to you, [who was] in a very important position in these negotiations, and told you to drag your heels; that, you know, "We want this thing to drag out. We don't want to give the Obama administration a victory." What are your thoughts on that?

If I were doing that, Sen. Baucus would not have stayed at the table. He and I know each other well enough; we understand each other.

The second thing is that the Group of Six would not have stayed together. I think Sen. [Mike] Enzi [R-Wyo.], Sen. [Olympia] Snowe [R-Maine] are very intellectually honest in those regards.

As a practical matter, just let me say it this way: We would not have spent 31 meetings with hundreds of hours just to drag our feet. We've got more important things to do. We were trying to get to a bottom line, and we'd made a lot of progress. There were still some controversial issues we didn't [work out].

But here is the best answer to your question. In fact, this should be the only answer to your question, when I think of it, and that is that the Republican leadership didn't have anything to do with this opposition that was growing. In fact, no leader of a party could organize the grassroots opposition that grew from the grassroots of America against this extreme piece of legislation that was being pushed by the other party. In other words, the other party, though maybe not because their members wanted it, but they were getting so much pressure from the extreme left to go with as much government control of health care as we can that they kind of pushed the Democrats away from the table to go partisan, and we Republicans were left there holding our hands as we didn't have anybody to negotiate with after roughly the middle of September.

So I don't want to denigrate Republican leadership in the Congress, but this, from the grassroots of America, so much had turned against this.

And let me suggest something to you, too, that I'm not sure that it's just health care. Health care was kind of the straw that broke the camel's back. I'd like to suggest to you that after General Motors is nationalized, after credit is effectively nationalized, after the stimulus bill didn't keep unemployment under 8 percent, after cap and trade passed the House, people started looking at ... health care costs, and they thought everybody in Washington went bananas. And so it was kind of a cumulation of things that you kind of looked like, "Well, it was just against health care." No. It was against the extreme. It looked like government was taking over everything at that point, and people were going to make sure they didn't take over our health care.

So you go home in the summer, and you start going to these town meetings. What do you find, and how surprised are you?

First of all, you've got to look at my town meetings ... starting in January. January through the Memorial Day break, most of the talk was about health care, and most of it was people just wanting information on health care.

And then the July 4 break comes. It's not anywhere as near like the August break in town meetings, but the July 4 break came, and it came right after the House passed cap and trade. It was the first time that I had what I would say is very violent feelings against health care reform that we were working on, and still I was in the Group of Six at that point.

And then it kind of -- much more show of opposition in the August recess. Nothing in Iowa like I saw on television in Missouri or Pennsylvania or Maryland, and there may have been other states, but those are the only three I remember. I visualize those town meetings, and a member of Congress did not have a chance to talk. In fact, one member of the Senate told me -- and it wasn't in those three states, in another state -- that he went to a town meeting, and he never had a chance to say anything.

Our town meetings may have looked on television like they were of that sort, but there was never a time that a person asked a question or expressed a view that they didn't have a chance to express it, and it seemed to me it was respected. I had every opportunity to give a thoughtful response.

But the anger was there? It sent a message?

I think that it was the first visible expression -- not to me; that came at the July 4 break -- but I think for the country as a whole it would look that way, because that's what they saw on television.

It's been said about you that you capitulated a bit. Someone had quoted that this was not a profile in courage, that you in some ways turned because of the pressures that were brought. What's your response to that?

All anybody has to do is look at what happened during the month of August. During the month of August, we had still our meetings, so we were still at the table then. When we came back after Labor Day, we were at the table, negotiating. And then about the middle of September, the Democrats decided to go political, go partisan. And so that's where it ended. There wasn't any capitulation on anybody's part on the Republican side. We were still at the table, but there was nobody on the other side of the table.

... We've got to talk about [Sen.] Scott Brown's [R-Mass.] election. What did the White House miss? ...

I think what they missed was an opportunity early on to do what they decided to do now that they like the Senate bill. They should have said, "We don't need a public option." They didn't have to say they were against the public option, just needed to say that they'd sign a bill without a public option.

They should have cooperated with members of both parties that wanted to put some sort of a cap on tax deductibility of insurance policies. There should have been an effort, a more cooperative effort on their part to hold off the extreme of their party that wanted Canadian-style health insurance or a public option that one of the members from Chicago said: "Well, we can't do a Canadian-style system right now. We've got to do a public option, because it's a step toward it."

It led everybody to believe in this country that there were people in Washington not listening to the grassroots, that wanted the government to take over health care. And they didn't do enough to quash that.

And the anger over things like the Nebraska deal and such.

That didn't happen until two weeks before Christmas, so you've got to understand: This thing was ready for burial back around November. And the reason why I say that is there was this grassroots uprising against it. It was an understanding that it increased taxes; it increased premiums; it took half a trillion out of Medicare, and that's already in trouble; and it didn't do anything about health care inflation.

And people were reading it. I had people come to my town meeting with sheaves of paper that thick off the Internet and quoting from the bill. I've never had that happen before. People were up on it, and people didn't like what they were reading.

And the anger, though, about the way Washington operated, like the Nebraska deal that some people say is just normal horse trading.

You know what my constituents told me in my town meetings? That those people that do that ought to go to jail. That was the reaction. Not just unethical, but it was really a crime in a sense.

... What message did [Scott Brown's election] send to the administration?

In one election was a composite of all that ill feeling from the grassroots of America against this dramatic takeover of health care by the government, and the people didn't want it. And if it can be expressed in liberal Massachusetts, they know it's a lot worse in Montana and Wyoming.

... [The president is] now saying that Washington is trying to drag down this proposal. He's trying to make Washington work. Washington won't work because it's playing the old political games, so he's taking back the mantle of being the outsider. Do you think that's a smart way to go? Do you think he's possibly going to be able to achieve that?

No, it reinforces what everybody knows about Washington. It's an island surrounded by reality. And he goes outside of Washington [to] have town meetings, but he's not really getting down to the grassroots of America. I know how this works. I know how it worked in the Bush administration. You give friends tickets to come to your town meeting, so you never get any negative questions.

... Another thing that people say is ... that Washington is broken. It can't achieve the big things. You've been here a long time; you've seen this work over and over; you've been very involved in bipartisan actions throughout your tenure. What's your attitude about this? Is Washington broken?

It's only broken from the standpoint that there's 60 of one party and 40 of the other. When there's 55 of one party and 45 of the other, we'll be able to get things done, because no one party will think they can do it all by themselves. That's what's wrong with this health care thing. They had 60 votes. They thought that "We've got a mandate to legislate. We've got to legislate and run over anybody and do anything extreme just to get something done, to have a victory."

The death of Sen. [Ted] Kennedy [D-Mass.], how badly did that hurt the Obama efforts? ...

Looking back on what took place the first eight months of last year, before he died and his not being on the scene during that period of time, I have to look back and say that the death did not make much difference. And I say that from the standpoint that if you want to ignore what grassroots America thinks, then his death made a difference. But there's nobody even as great as the lion of Massachusetts is, or the lion of the Senate is, that can overcome the massive ill feeling about this piece of legislation by the American people at this point. And again, I emphasize it's not just this piece of legislation; it's the culmination of a lot of things that went on in the previous eight months.

... [Former Sen. Tom Daschle (D-S.D.)] was going to play a very important role [as secretary of health and human services]. Some people say that you guys vetted him harshly. ... What was the effect of the loss of Daschle to the Obama [administration]?

I don't know. But he wasn't vetted any different than anybody else in the last 10 years that Sen. Baucus and I have led this committee.

... What's the lesson to be learned from watching over this whole thing?

I think President Obama was elected on a platform based on his campaign, and he campaigned against an individual mandate. He campaigned against complete government takeover of health care, contrary to what Mrs. Clinton wanted to do. And the lesson to learn: You ought to serve on the platform you run on. And if he had served on the platform he'd run on, we'd have a health care bill passed by now.

He also said he wouldn't deal with special interests.

And I think he made a bad deal, because Big Pharma is not going to make a deal that they're going to kick in $80 billion without knowing they're going to get $2 back for every $1 they put in. And if you look at how the "doughnut hole" is filled, I can show you exactly how they're going to get back $2 for every one they put in.