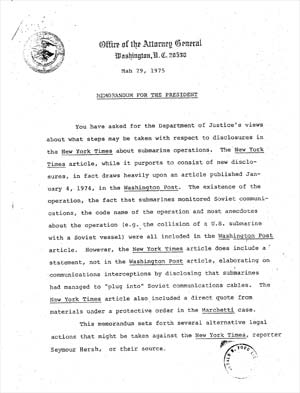

Office of the Attorney General

Washington, D.C. 20530

March 29, 1975

MEMORANDUM FOR THE PRESIDENT

You have asked for the Department of Justice's views about what steps may be taken with respect to disclosures in the New York Times about submarine operations. The New York Times article, while it purports to consist of new disclosures, in fact draws heavily upon an article published January 4, 1974, in the Washington Post. The existence of the operation, the fact that submarines monitored Soviet communications, the code name of the operation and most anecdotes about the operation (e.g. the collision of a U.S. submarine with a Soviet vessel) were all included in the Washington Post article. However, the New York Times article does include a statement, not in the Washington Post article, elaborating on communications interceptions by disclosing that submarines had managed to "plug into" Soviet communications cables. The New York Times article also included a direct quote from materials under a protective order in the Marchetti case.

This memorandum sets forth several alternative legal actions that might be taken against the New York Times, reporter Seymour Hersh, or their source.

Each of these alternatives involves two serious problems: First, the previous publication of much of the material in the Washington Post makes legal action less attractive since the government could not take the position that the entire article constituted a new disclosure of classified material but would rather have to attack only a few isolated paragraphs which went beyond previous disclosures. Second, in any legal action the government would have to admit -- and, indeed prove -- that the undersea communications intelligence operation both existed and was classified. This would put an official stamp of truth on the article and could have diplomatic consequences which would otherwise not follow from an unofficial account.

The legal options are:

I. Prosecutions Under the Espionage Act

A. Prosecution of the New York Times or Hersch under 18 U.S.C. 798 (a) (3) for knowing disclosure of classified information concerning the communications intelligence activities of the United States. The sole aspect of the story to which Sec .798 might be applicable is the paragraph concerning U.S. submarines plugging in to Soviet undersea cables.

Sec. 798 has never been used and there is no judicial interpretation of its proof requirements. Prosecution under 798 could rest upon the fact of publication and would not then require subpoenaing newspapermen and newspaper files to identify sources for further prosecution. This has the advantage of minimizing First Amendment litigation and adverse public reaction. It has the disadvantage that the persons who leaked the classified information will hot be prosecuted.

The alternative is to run a grand jury investigation in order to identify and prosecute the sources of the leaks under 798. It is predictable, however, that Hersh would refuse to name his sources, even if he were granted immunity to avoid the issue of self-incrimination, and would accept imprisonment for contempt. This would turn the case into a journalistic cause celebre without securing any conviction on the merits.

The least controversial use of 798 would be prosecution of the Times alone. Since only a fine and not imprisonment would be at stake, the prosecution would be viewed as in the nature of a test case to establish the scope of the government's power to protect sensitive information. This course, however, might be less likely to deter Hersh from publication of additional classified information.

Sec. 798 appears to offer the most promising basis for prosecution but there are unresolved legal issues, e.g., whether the defendant's knowledge that the information was classified may be inferred by a jury from the nature of the information without more.

B. Prosecution could also be brought under Section 793, the Espionage Act. Unlike Section 798, this section is not limited in scope to communications intelligence information. Subsection (d) prohibits a person who has lawful possession of information relating to the national defense from communicating or delivering such information to a person not entitled to receive it. This means that the reporter and the news paper could not be prosecuted under this subsection, but their sources presumably could.

Prosecution under this subsection would require proof of the following elements:

- Proof of the source of the newspaper's information. As pointed out earlier, in all probability, evidence on this point could be obtained only if the reporter divulged his sources, which is unlikely. This course would also turn the case into a cause celebre without securing any conviction on the merits.

- Proof that the information disclosed was accurate and related to national security.

- Proof that the government has made an affirmative effort to prevent dissemination and that the information is not in the public domain. This. element would require the government to focus its case on two paragraphs, one referring to the interception of communications on Soviet undersea cables, and the other quoting a CIA memorandum involved in the Marchetti case. The remaining portion of the story has, by and large, been in the public domain for more than one year, having been published in the Washington Post.

Subsection (e) proscribes the same conduct as subsection (d) and applies to those in unlawful possession of national security information. Accordingly, this subsection could be the basis for a prosecution of the reporter and the New York Times company. This subsection would also require proof that there was knowledge that the information is classified and that it relates to the national security. Again, this course would require the government to verify the accuracy and pensitivity of the information disclosed.

As to Section 793, there is an argument that its provisions do not cover publication since its express terms apply only to "communications." In the Pentagon Papers case the justices expressed varying views on this issue. It is our view this section would cover publication.

II. Action in Connection With the Marchetti Litigation

The New York Times article quotes from a document covered by a protective order issued in the Marchetti litigation (which concerns disclosures in a book titled, The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence). The quotation leaves out information that was masked in the document as it appeared in records of the litigation, thus indicating the New York Times may have obtained the document in violation of the court order.

A. One alternative would be to commence a criminal contempt proceeding in connection with the Marchetti litigation, requesting that the Court issue an order requiring all those persons who had access to the documents involved in the case to state whether they furnished the documents to the journalist. The difficulties with this option are:

- The Court may refuse to issue such an order on the grounds that the government has no evidence reflecting a violation of the protective order. A prior government effort to petition the Court to take action upon publication of a Washington Post article in 1974 failed. A new request would very probably fail and might cause the judge to issue a public rebuke of the government.

- Various judges, law clerks, and government counsel have had access to the documents so we have no factual basis to point a finger at the plaintiffs' camp.

- The New York Times article hints that the information was derived from interviews with past and present government officials who know of the program.

- Even if the Court were to issue an order, presumably all of the persons who had access would claim a Fifth Amendment privilege.

For these reasons, the government would no doubt be stymied and perhaps embarrassed by what might appear to be a feeble effort to get at the source of the violation of the protective order and the leakage of classified information.

B. Another alternative would be to use a grand jury to investigate a possible criminal contempt of the Court's protective order. The grand jury could subpoena anyone having access to the documents and the journalist. It could grant immunity to any witness which would negate a Fifth Amendment privilege. The difficulties with this course of action are:

- The journalist would presumably refuse to identify the source, thus provoking a Branzburg v. Hayes, 408 U.S. 665, confrontation.

- The leaks contain greater information than was in the Marchetti documents and the remedy of criminal contempt might, thus, fall short of the appropriate remedies needed.

C. It has been suggested that we might ask the Court to amend the protective order to cover the New York Times. This possibility does not seem feasible or appropriate. The Times is not a party to the litigation, and we cannot demonstrate that they acted in concert with parties in violation of the protective order. We have serious doubts that the Court would act favorably on such a request. In short, we have no basis to broaden the coverage of the protective order simply because the Times published classified information.

D. In order to restrain future publication by the Times, we would have to move for an injunction. This motion we would have to move for would clearly have to comply with the stringent burdens of New York Times v. United States , 403 U.S. 714 (1971). (Pentagon Papers Case) That would be impossible unless we could prove "direct, immediate, and irreparable damage" and not merely "substantial damage" to the national interest.

III. Recommendation

It is my view that the most promising course of action, for the moment, would be to discuss the problem of publication of material detrimental to the national security with leading publishers. Should you desire, I would be glad to undertake such discussions.

Edward H. Levi

Attorney General

![News War [site home page]](../art/p_title.gif)