In 1971, when The New York Times was fighting to publish the Pentagon Papers, Times Washington Bureau Chief Max Frankel filed this deposition in which he details how leaks are the way Washington runs -- its "currency." As he explains, leaks were an unofficial back channel for testing policy ideas and government initiatives. In this deposition, Frankel lists several examples in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations of how government kept secrets, but also used them, and leaked them, when it served their purpose.

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

-----------------------------------------------x

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, :

Plaintiff, :

:71 Civ. 2662

-v- :

:

NEW YORK TIMES COMPANY, et. al., :

Defendants. :

------------------------------------------------x

STATE OF NEW YORK)

: ss. :

COUNTY OF NEW YORK)

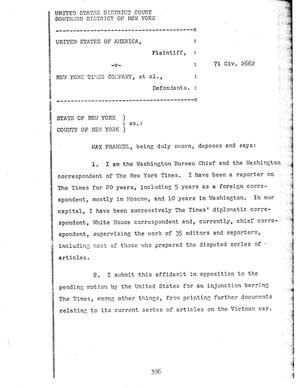

MAX FRANKEL, being duly sworn, deposes and says:

1. I am the Washington Bureau Chief and the Washington correspondent of The New York Times. I have been a reporter on The Times for 20 years, including 5 years as a foreign correspondent, mostly in Moscow, and 10 years in Washington. In our capital, I have been successively The Times' diplomatic correspondent, White House correspondent and, currently, chief correspondent, supervising the work of 35 editors and reporters, including most of those who prepared the disputed series of articles.

2. I submit this affidavit in opposition to the pending motion by the United States for an injunction barring The Times, among other things, from printing further documents relating to its current series of articles on the Vietnam war.

"Secrecy" in Washington

3. The Government's unprecedented challenge to The Times in the case of the Pentagon papers, I am convinced, cannot be understood, or decided, without an appreciation of the manner in which a small and specialized corps of reporters and a few hundred American officials regularly make use of so-called classified, secret, and top secret information and documentation. It is a cooperative, competitive, antagonistic and arcane relationship. I have learned, over the years, that it mystifies even experienced government professionals in many fields, including those with Government experience, and including the most astute politicians and attorneys.

4. Without the use of "secrets" that I shall attempt to explain in this affidavit, there could be no adequate diplomatic, military and political reporting of the kind our people take for granted, either abroad or in Washington and there could be no mature system of communication between the Government and the people. That is one reason why the sudden complaint by one party to these regular dealings strikes us as monstrous and hypocritical -- unless it is essentially perfunctory, for the purpose of retaining some discipline over the Federal bureaucracy.

5. I know how strange all this must sound. We have been taught, particularly in the past generation of spy scares and Cold War, to think of secrets as secrets -- varying in their "sensitivity" but uniformly essential to the private conduct of diplomatic and military affairs and somehow detrimental to the national interest if prematurely disclosed. By the standards of official Washington -- Government and press alike -- this is an antiquated, quaint and romantic view. For practically everything that our Government does, plans, thinks, hears and contemplates in the realms of foreign policy is stamped and treated as secret -- and then unraveled by that same Government, by the Congress and by the press in one continuing round of professional and social contacts and cooperative and competitive exchanges of information.

6. The governmental, political and personal interests of the participants are inseparable in this process. Presidents make "secret" decisions only to reveal them for the purposes of frightening an adversary nation, wooing a friendly electorate, protecting their reputations. The military services conduct "secret" research in weaponry only to reveal it for the purpose of enhancing their budgets, appearing superior or inferior to a foreign army, gaining the vote of a congressman or the favor of a contractor. The Navy uses secret information to run down the weaponry of the Air Force. The Army passes on secret information to prove its superiority to the Marine Corps. High officials of the Government reveal secrets in the search for support of their policies, or to help sabotage the plans and policies of rival departments. Middle-rank officials of government reveal secrets so as to attract the attention of their superiors or to lobby against he orders of those superiors. Though not the only vehicle for this traffic in secrets -- the Congress is always eager to provide a forum -- the press is probably the most important.

7. In the field of foreign affairs, only rarely does our Government give full public information to the press for the direct purpose of simply informing the people. For the most part, the press obtains significant information bearing on foreign policy only because it has managed to make itself a party to confidential materials, and of value in transmitting these materials from government to other branches and offices of government as well as to the public at large. This is why the press has been wisely and correctly called The Fourth Branch of Government.

8. I remember during my first month in Washington, in 1961, how President Kennedy tried to demonstrate his "toughness" toward the Communists after they built the Berlin wall by having relayed to me some direct-quotations of his best arguments to Foreign Minister Gromyko. We were permitted to quote from this conversation and did so. Nevertheless, the record of the conversation was then, and remains today, a "secret."

9. I remember a year later, at the height of the Cuban missile crises, a State Department official concluding that it would surely be in the country's interest to demonstrate the perfidy of the same Mr. Gromyko as he denied any knowledge of those missiles in another talk with the President; the official returned within the hour and let me take verbatim notes of the Kennedy-Gromyko transcript -- providing only that I would not use direct quotations. We printed the conversation between the President and the Foreign Minister in the third person, even though the record probably remains a "secret."

10. I remember President Johnson standing beside me, waist-deep in his Texas swimming pool, recounting for more than an hour his conversation the day before, in 1967, with Prime Minister Kosygin of the Soviet Union at Glassboro, N.J., for my "background" information, and subsequent though not immediate use in print, with a few special off-the-record sidelights that remain confidential.

111. I remember Secretary of State Dean Rusk telling me at my first private meeting with him in 1961 that Laos is not worth the life of a single Kansas farm boy and that the SEATO treaty, which he sould [sic] later invoke so elaborately in defense of the intervention in Vietnam, was a useless instrument that should be retained only because it would cause too much diplomatic difficulty to abolish it.

12. Similar dealings with high officials continue to this day.

13. We have printed stories of high officials of this Administration berating their colleagues and challenging even the President's judgment about Soviet activities in Cuba last year.

14. We have printed official explanations of why American intelligence gathering was delayed while the Russians moved missiles to the Suez Canal last year.

15. These random recollections are offered here not as a systematic collection of secrets made known to me for many, usually self-evident (and also self-serving) reasons. Respect for sources and for many of the secrets prevents a truly detailed accounting, even for this urgent purpose. But I hope I have begun to convey the very loose and special way in which "classified" information and documentation is regularly employed by our government. Its purpose is not to amuse or flatter a reporter whom many have come to trust, but variously to impress him with their stewardship of the country, to solicit specific publicity, to push out diplomatically useful information without official responsibility, and, occasionally, even to explain and illustrate a policy that can be publicly described in only the vaguest terms.

16. This is the coin of our business and of the officials with whom we regularly deal. In almost every case, it is secret information and much of the time, it is top secret. But the good reporter in Washington, in Saigon, or at the United Nations, gains access to such information and such sources because they wish to use him for loyal purposes of government while he wishes to use them to learn what he can in the service of his readers. Learning always to trust each other to some extent, and never to trust each other fully -- for their purposes are often contradictory or downright antagonistic -- the reporter and the official trespass regularly, customarily, easily, and unselfconsciously (even unconsciously) through what they both know to be official "secrets." The reporter knows always to protect his sources and is expected to protect military secrets about troop movements and the like. He also learns to cross-check his information and to nurse it until an insight or story has turned tripe. The official knows, if he wishes to preserve this valuable channel and outlet, to protect his credibility and the deeper purpose that he is trying to serve.

The Role of "Classified" Information

17. I turn now in an attempt to explain, from a reporter's point of view, the several ways in which "classified" information figures in our relations with government. The Government's complaint against The Times in the present case comes with ill-grace because Government itself has regularly and consistently, over the decades, violated the conditions it suddenly seeks to impose upon us -- in three distinct ways:

First, it is our regular partner in the informal but customary traffic in secret information, without even the pretense of legal or formal "declassification." Presumably, many of the "secrets" I cited above, and all the "secret" documents and pieces of information that form the basis of the many newspaper stories that are attached hereto, remain "secret" in their official designation.

Second, the Government and its officials regularly and customarily engage in a kind of ad hoc, de facto "declassification" that normally has no bearing whatever on considerations of the national interest. To promote a political, personal, bureaucratic or even commercial interest, incumbent officials and officials who return to civilian life are constantly revealing the secrets entrusted to them. They use them to barter with the Congress or the press, to curry favor with foreign governments and officials from whom they seek information in return. They use them freely, and with a startling record of impunity, in their memoirs and other writings.

Third, the Government and its officials regularly and routinely misuse and abuse the "classification" of information, either by imposing secrecy where none is justified or by retaining it long after the justification has become invalid, for simple reasons of political or bureaucratic convenience. To hide mistakes of judgment, to protect reputations of individuals, to cover up the loss and waste of funds, almost everything in government is kept secret for a time and, in the foreign policy field, classified as "secret" and "sensitive" beyond any rule of law or reason. Every minor official can testify to this fact.

18. Obviously, there is need for some secrecy in foreign and military affairs. Considerations of security and tactical flexibility require it, though usually for only brief periods of time. The Government seeks with secrets not only to protect against enemies but also to serve the friendship of allies. Virtually every mature reporter respects that necessity and protects secrets and confidences that plainly serve it.

19. But for the vast majority of "secrets," there has developed between the Government and the press (and Congress) a rather simple rule of thumb: The Government hides what it can, pleading necessity as long as it can, and the press pries out what it can, pleading a need and a right to know. Each side in this "game" regularly "wins" and "loses" a round or two. Each fights with the weapons at its command. When the Government loses a secret or two, it simply adjusts to a new reality. When the press loses a quest or two, it simply reports (or misreports) as best it can. Or so it has been, until this moment.

Some Examples

20. Some of the most powerful examples of the widespread traffic in secret information that I describe were found by a few colleagues in the Washington bureau in a most perfunctory search of our files. Even as I write this affidavit I can glance at the Times of June 16, 1971 and find, beside the headline of the Court's temporary restraining order in this case, a sample from our military correspondent, William Beecher:

WASHINGTON--June 15--The Nixon Administration is engaged in a broad policy review aimed at determining course of action that might improve South Vietnam's ability to withstand military assaults next year, after most American forces have been withdrawn…

Other key developments include an estimate by the National Security Council that North Vietnam is building toward a new offensive in the South next year….

Well-placed Administration sources disclose that, against the expected North Vietnamese threat, officials are focusing on the following major questions….

Many planners expect President Nixon to scale down to a residual force of 30,000 to 70,000 men by July 1, 1972, but to leave enough flexibility in the pace of reductions so that many of them can be timed for May and June…

Should this residual force include many helicopter and artillery units to "stiffen" South Vietnamese defenses….

Not a single source of that information is identified by name, either because sources are peddling information for which they have asked not to be held responsible or because they are revealing information without authorization. Either way, they are relaying secret data which we, judging by other confidential contacts, deem reasonably reliable.

21. Some of the best examples of the regular traffic I describe may be found in the Pentagon papers that the Government asks us not to publish. The uses of top secret information by our Government in deliberate leaks to the press for the purposes of influencing public opinion are recorded, cited and commented upon in several places of the study. Also cited and analyzed are numerous examples of how the Government tried to control the release of such secret information so as to have it appear at a desired time, or in a desired publication, or in a deliberately loud or soft manner for maximum or minimum impact, as desired.

22. The temporary restraining order currently in effect precludes me from citing and quoting these passages in the Pentagon study. Examples of my point are so numerous that despite the great bulk of the papers, we were able to locate more than a dozen different kinds of such passages in less than an hour.

23. Extensive samples of stories plainly based on supposedly secret information are annexed to this affidavit. They include not only regular, daily articles but also major contemporary analyses of Government decision-making at several key stages of the Vietnam war, right after the Cuban missile crisis, and shortly after invasion of Cambodia. They include major journalistic investigations of secret institutions, like the Central Intelligence Agency. They combine known facts, pried-out secrets and deliberate disclosures of secrets. They are recognized within the profession and among readers as they most valuable kind of journalism and have never been shown to cause "irreparable" harm to the national security. They have occasionally prompted investigations inside the Government to determine the sources of information, the possible presence of disloyal or dissenting officials or the existence of information not previously given any weight or credibility by higher authority. None of these articles could be fairly described as less "sensitive" or more innocuous than the materials now challenged. None of them ever produced a legal challenge or a request for new legislation.

24. Samples of the second kind of traffic in secrets that I mentioned -- the ad hoc, de facto (but by no means authorized, official or "legal") declassification of documents -- are simply too numerous sand too voluminous to collect in this format and on such short notice.

25. George Christian of Austin, Tex., former press secretary to President Johnson, who had free admission to all foreign and domestic discussions involving the President, at any level and in any forum, has already published his memoir. It includes 70 pages of narrative on the decisions to end the bombing of North Vietnam in late 1968, with many direct quotations of the President and other officials, many unflattering references to our allies in South Vietnam and a great deal of detailed information, all still highly classified, about the secret negotiations with North Vietnam in Paris. This book, entitled, "The President Steps Down," (MacMillan, 1970), actually covers a period more recent than that discussed in the Pentagon papers, and at a much higher level of government and secrecy.

26. Recently a book containing top secret documents from members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff about the very same period covered by The Times' materials was published. The book, entitled "Roots of Involvement," by Marvin Kalb and Elie Abel (pp. 208-212) includes telegram exchanges between General Westmoreland and General Wheeler in early 1968. We are advised that these texts were taken from privately circulated analyses and histories of phases of the war by leading military commanders still on active duty!

27. Theodore C. Sorensen's "Kennedy," written within a year of the death of his President, reveals dozens upon dozens of actions, meetings, reports and documents, all still treated as "classified" by the Government and unavailable for more objective journalistic analysis. Sorensen treated the Kennedy-Khrushchev correspondence as private, to protect future channels of communication with Soviet leaders, but the most "secret" of these letters, during the Cuban missile crisis, were fully revealed in two subsequent books, one by Elie Abel and one by Robert F. Kennedy. Sorensen also observes that while Kennedy was still alive he invited Professor Richard Neustadt into Government archives for a contemporary analysis of decision-making of the "Skybolt" affair, the secrets of which were later revealed by the professor in a public account of this minor-missile crisis with Britain.

28. Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., kept notes in the White House for his history of the Kennedy years entitled "A Thousand Days." Roger Hilsman, an intelligence officer and then Assistant Secretary of State for the Far East poured his files and secrets into a quick memoir entitled "To Move a Nation" (Doubleday 1967). John Martin, special ambassador during the Dominican Republic invasion of 1965, wrote "Overtaken by Events," (Doubleday, 1966) recounting numerous confidential messages and communications. Chester Cooper, a C.I.A. official involved in Vietnam policy for two decades left the White House to produce what was probably the most complete and best-documented history until the Pentagon papers became available to The Times. "The Secret Search for Peace in Vietnam," by David Kraslow and Stuart Loory of The Los Angeles Times, remains to this day the most thorough newspaper (and book) account of the diplomacy surrounding the war -- through channels that are still deemed "live".

The Pentagon Study

29. As The Times indicated in the first of its articles about the Pentagon study that is in question here, it is a massive history of how the United States went to war in Indochina. Its 3,000-page analysis, to which 4,000 pages of official documents are appended, was commissioned by Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara in 1967 and completed in 1968, by which time he had been replaced by Clark M. Clifford. The analysis covers a historical record, as The Times said, from World War II to May, 1968 -- the start of peace talks in Paris, by which time President Johnson had set a limit on further military commitments and revealed his intention to retire. We said that "though far from a complete history, even at 2.5 million words, the study forms a great archive of government decision-making on Indochina over three decades." That was the most concise journalistic definition we could give to the materials. Examination of our report thus far on the study and presentation of its documentation confirms the accuracy of that definition.

30. Moreover, the material was treated by The Times as an historical record that was of importance not only to our daily readers but also to the community of scholars that we have long served with a record of events. Our presentation was subjected to the most careful editing so that our report would remain faithful to the Pentagon record itself.

31. It is difficult, while publication is suspended, to describe the content and scope of the material. But our first article has already established the framework for our readers. We said the authors of the study reached many broad conclusions and specific findings, including the following:

(a) "--That the Truman Administration's decision to give military aid to France in her colonial war against the Communist led Vietminh 'directly involved' the United States in Vietnam and 'set' the course of American policy.

(b) "--That the Eisenhower Administration's decision to rescue a fledgling South Vietnam from a Communist takeover and attempt to undermine the new Communist regime of North Vietnam gave the Administration a 'direct role in the ultimate breakdown of the Geneva settlement' for Indochina in 1954.

(c) "--That the Kennedy Administration, though ultimately spared from major escalation decisions by the death of its leader, transformed a policy of 'limited-risk gamble,' which it inherited, into a 'broad commitment' that left President Johnson with a choice between more war and withdrawal.

(d) "--That the Johnson Administration, though the President was reluctant and hesitant to take the final decision, intensified the covert warfare against North Vietnam and began planning in the spring of 1964 to wage overt war, a full year before it publicly revealed the depth of its involvement and its fear of defeat.

(e) "--That this campaign of growing clandestine military pressure through 1964 and the expanding program of bombing North Vietnam in 1965 were begun despite the judgment of the Government's intelligence community that the measures would not cause Hanoi to cease its support of the Vietcong insurgency in the South, and that the bombing was deemed militarily ineffective within a few months.

(f) "--That these four succeeding Administrations built up the American political, military and psychological stakes in Indochina, often more deeply than they realized at the time, with large-scale military equipment to the French in 1950; with acts of sabotage and terror warfare against North Vietnam beginning in 1954; with moves that encouraged and abetted the overthrow of President Ngo Dinh Diem of South Vietnam in 1963; with plans, pledges and threats of further action that sprang to life in the Tonkin Gulf clashes in August, 1964; with the careful preparation of public opinion for the years of open warfare that were to follow; and with the calculation in 1965, as the planes and troops were openly committed to sustain combat, that neither accommodation inside South Vietnam would achieve the desired result."

(g) Further characterizing the materials, our introduction also indicated revelations "about the ways in which several administrations conducted their business on a fateful course, with much new information about the roles of dozens of senior officials of both major political parties and a whole generation of military commanders."

32. The Times found the history to be concerned primarily with the decision-making process in Washington and the thoughts, motives, plans, debates and calculations of the decisionmakers. I have seen no materials bearing on future plans of a diplomatic or military nature.

The Times interest throughout, like that of the study itself, in the words of our opening line, was in "how the United States went to war in Indochina."

33. In considering the remainder of the material, in preparation for publication, it is difficult to be precise, without compromising our deep conviction that no agency of Government ought to be placed in the position of approving, or being asked to approve, prior to publication, any article or other materials that we plan to publish in the exercise of our profession.

34. But it may be helpful to affirm to the Court what is already plain from what we have published so far. The remaining articles will be of the same historical character as the first three, similarly dealing with the decision-making process and the thoughts, debates and calculations of the decision-makers.

35. Of the numbered paragraphs in our original introduction to the first article, the materials and accounts bearing on paragraphs (4) and (5) and a part of (6) -- covering the period from early 1964 to the middle of 1965 -- have already appeared in print. The remainder of the introduction was deemed by us to be a fair journalistic summary of the remainder of our story.

36. Within the limits we have set on the discussion of our unpublished articles, we can state that the stories will cover, as we have indicated, the origins of the United States involvement in Southeast Asia from World War II forward, in the broad context of our evolving policy for the Pacific, through the period of the Eisenhower Administration and the Geneva conference on Indochina. They will cover the history of policymaking inherited by President Kennedy and the Kennedy years, including the broad perspective of those years, which involved the specific problem of political stability culminating in the overthrow of President Ngo Dinh Diem. Among other things, our stories will also cover the history of other policy decisions through early 1968, including the personal disillusionment with policy felt by Secretary McNamara and the roles of other policymakers.

37. The Pentagon papers published and to be published by the Times and a bureaucratic history and analysis of the interaction of events and policy decisions are an invaluable historical record of a momentous era in our history. We cannot believe they should or will be suppressed.

[Signed]

Max Frankel

Sworn to before me this

17th day of June, 1971

[signed]

Mary Ann C. Simpson

Notary Public, State of New York

No. 41-3582775

Qualified in Queens County

Commission Expires March 30, 1973

![News War [site home page]](../art/p_title.gif)