- Some highlights from this interview

- Is a news anchor a reporter?

- A history of confrontations with the Bush family

- The risks and benefits of going to work for billionaire Mark Cuban

- The "Rathergate" fallout

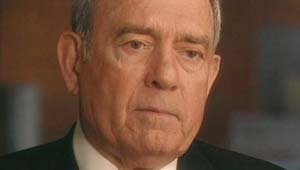

After gaining national notoriety as CBS's Dallas correspondent covering the assassination of President Kennedy, Rather joined the CBS News national desk in 1964. He replaced Walter Cronkite as anchor of the CBS Evening News in 1981 and held that position for 24 years. He also worked as a correspondent for 60 Minutes and 60 Minutes II and as the anchor of 48 Hours. He left CBS in 2005 after retracting a 60 Minutes II report about President Bush's service with the National Guard that had been based on fraudulent documents. Today, he is the managing editor and anchor of the fledgling Dan Rather Reports on Mark Cuban's HDNet. This is the edited transcript of an interview conducted on Sept. 13, 2006.

When we were interviewing John Carroll, the former executive editor of the L.A. Times, he said that in his recent studies that 80 percent or more of the new information gathered every day is still gathered by newspapers.

I wouldn't dispute that. I think that's probably true. I've not done any study, ... but what happens in your average newsroom is that people read the newspaper. Yes, they read the Internet increasingly now, but they read the newspaper and get story ideas out of the newspaper. It's not unusual just to lift things straight out of the newspaper. The better operations make some attempt to give credit; the others don't. But I think that's probably true. ...

At one time, when you got involved in television news and when it was evolving into a larger and larger organization, it was gathering its own news.

It was gathering a lot of its own news. What happened is that in the very beginning, newspaper owners were very wary of radio as a competitor -- we're talking now in the very late '20s and the early '30s -- so much so [that], ... for example, for some years, a radio network could not use the AP [Associated Press] material because the newspaper barons, who were the most powerful in journalism at the time, said, "Listen, radio stations should not be able to use our collective material off the AP."

Meanwhile, as radio matured and developed -- primarily because of Ed Murrow and Bill Shirer [who together pioneered radio coverage of events in Europe in the 1930s, particularly in Germany] -- radio began to say, "We need to cover news on our own." This was the starting of radio operations -- by no means all, but particularly radio networks -- forming their own newsgathering operations, and that grew over time.

Then as radio became a mature business and television began to come on after World War II, and ... as television began to grow and to mature, the television news operations, and in particular the networks, had their own newsgathering operations.

I would say that the high watermark of that probably was reached in the late 1970s and early 1980s. That is when television news operations and particularly local stations were at their absolute height of having newsgathering operations, as opposed to just news-packaging [operations]. ... Increasingly what has happened in television is that television news has morphed from an emphasis on newsgathering -- gathering their own news -- into an emphasis on news packaging; that is, we will take news that's gathered by other people -- what's called in the other businesses "outsourcing." We will outsource the gathering of news. We will buy film from Reuters or from a stringer in South Africa, and then we will package it. …

“There certainly is a school of thought that says: 'Don't make any waves.' … Once you start thinking that way, once you let that get into your head, you're through as a reporter.”

Radio and television stations are licensed by the Federal Communications Commission. The airwaves are public property. The point is, there was a strong sense that we need to [provide news programming], one, because it is a public service; two, because there's a requirement that we do a certain amount of public service in order to get our license to operate renewed -- and one shouldn't underestimate that as a motivation; then three, particularly the local stations [felt] if we can make money doing it, all the better. ...

Let me take you back to when you got involved at CBS and met your colleagues in New York. What was your impression of CBS News?

Well, when I first came to CBS in early 1962, ... I thought I was a pretty good reporter with the arrogance or conceit of youth. I'd been paid as a reporter for well over 10 years, and yes, I thought I could write. But my first impression, which I remember, was just, "Wow."

One, I was walking the halls with legends: Charles Collingwood; Ed Murrow had just left -- I'd met Murrow in another circumstance; Eric Sevareid. The halls were filled literally with walking legends and already members of the Hall of Fame. Two, they could all write extremely well. One of my first impressions was, if I'm going to stay here in the big leagues, I'm going to have to learn to write a whole lot better.

But the central thing that impressed me was their spirit of mission. They saw their work -- their life's work -- as something bigger than themselves. ... To do quality news of integrity in the public service. ... And that permeated the halls of CBS News. You could smell it, see it, hear it, feel it. The strongest early reaction was, what a powerful sense of mission these people have.

They were journalists?

Oh, they were journalists. As a matter of fact, they didn't like to think of themselves as television people. Remember, this is 1962 when I first came to New York, and most of the people at CBS News had come out of a newspaper background and/or a radio background. ... But they didn't like to be described as television correspondents, or for that matter even radio correspondents. The word to use was "journalists." ...

The reality is that in American journalism, ... things have changed; things have changed greatly. The major television news operations are all owned by huge, international conglomerates, and the effect of that is manifold.

Number one, the large corporations, the conglomerates that now own, I would say, 80 to 85 percent of the major American news outlets, have many more interests besides news. They have great needs and wants, regulatory and legislative, in Washington. They are intertwined with the political process and with political power much more than they have ever been. The corporations contribute to political campaigns; they run very large lobbying operations. ... That's a reality in almost every major newsroom in the country. In fact, in major newsrooms, I don't know of any exception. So this is one thing to have in mind.

The second thing to have in mind is, because of their size, there's a tremendous communications gap between the leadership, the very top ownership, and the lead in the newsrooms. Now, even in the time of Ed Murrow and [CBS founder] Bill Paley in the late 1950s, when Murrow had his showdown about news values versus entertainment values, there was some of this. But here's the point: News is such a small part of the average conglomerate that owns major news outlets now, such a small part of the business, that the person who owns the business rarely has any real contact with the news operation, where when Bill Paley owned CBS News, he was in direct and regular contact with the news division and people within the news division, and he knew them. I think the record clearly shows that Mr. Paley had a strong sense of his responsibility of shepherding news, helping news as a public service at least part of the time. ...

Today, the idea is, just don't make any waves; just don't cause trouble. Nobody in the corporate superstructure of one of these conglomerates wants trouble. It's not that they're Republican or Democrat or they have some ideological agenda. They may have, but their main thing is, don't do anything that may rock the stock price. ... The effect has been now to drain out the sense of public service out of television news to the point where it's almost completely gone. ...

... When the news division or the network or the corporation comes to the news division and says, "This is what you're going to do, and this is what you're not going to do," as an employee of the corporation -- enjoying a good salary, benefits, the prestige of the organization -- the idea of defying the organization or publicly going against the organization means you risk all of that.

Well, that's true. But this is important: Rarely does anybody in the corporation come to you and say, "This is what we want you to do or not do." Now, in some specific cases -- some of which I've been involved in, some of which I haven't been involved in -- that has happened, but that's not the way it generally works. ... So what we're talking about in a large measure here is a kind of self-censorship, knowing full well what the reaction of the corporation would be.

Now, you and I know, and I think most people in the public know if they stop and think about it, that hard, straight news needs backers who don't back down, who don't back away. When you do an investigative story that you know is going to cause a whirlwind in terms of backlash from the government, from big sponsors, from competitors and what have you, what's very important is to know that the people at the top will back you up. ... I would say, up until some time in the mid-1980s, the record and the reality of working in network news is that you could do the tough stuff. ... While top management might not like it -- they might be a little uncomfortable with it -- they would back you; otherwise, we would never have had Watergate. ...

Now, as things begin to change in the 1980s, the atmosphere began to change, and by the time we got to 9/11 and post-9/11, things had changed to the degree that, as a reporter -- even a well-known one, a well-paid one, one that would have some power -- would have to think once, twice and three times about taking on the most powerful interest in the country, because you could no longer be certain you'd have the backup at the top.

Well, let me take you back for a minute to becoming an anchor. In your mind, when you became an anchor, you're no longer going to be a reporter, right?

No, the direct opposite in my mind: I believed then and believe now that most of what got me to the anchor chair was that I had been a field reporter for a long time. ... But I had covered the civil rights movement and Dr. Martin Luther King; the assassination of President Kennedy; covered Vietnam; was on point during the Watergate time. ... I had a record as a reporter, and I came to the anchor chair saying to myself: "There are a lot of things I don't know about this anchoring business. There are going to be a lot of problems that I can't even anticipate, but I'd better be true to myself."

I came to the anchor chair of the CBS Evening News in my mind saying, "What I want to be is a reporter-anchor, not an anchor-reporter. ... And I want 'reporter' to be in all caps, underlined and italicized." Now, I had the idea -- and I wasn't the only one -- that given the new technology that we could do the broadcast from anyplace on earth, and that would allow me to leverage my reporter skills and meld them into being a new kind of anchor, if you will. Others are going to have to judge how well or how poorly we did, but that was the concept. ...

But what was said to me at the time is: "Dan, you've been a field reporter for nearly all of your career. You have to set that aside and now think of yourself as an anchor, as a television personality. That's a different thing." And I considered that, but I rejected it for better or for worse. ...

I know you say "anchor-reporter," but you're still more distant from the actual events, the actual stories themselves.

[But] what I tried to do -- and the reason I said I wanted to think of myself and did think of myself as a reporter-anchor is there's a strong undertow when you're an anchor to put increasing amounts of distance between you and the journalistic work -- I tried to resist that. I thought it was a way, maybe one wee, small way, in which I could be a better anchor, that I didn't want to lose my reporting roots. I never lost sight of the danger that you've outlined. ...

I wanted to get in early, stay late, make it 24/7 about news and, insofar as it was possible as an anchor, to do what reporters do: make telephone calls, go see people, look into things. And I did some of that, and I think the record is pretty clear that I did.

But fundamentally your role is as a news reader?

No. Not at CBS News, not on the CBS Evening News with Dan Rather. That was not fundamentally my role, to be a reader. I always considered reading the news the least of things. ...

Now, I guess what I'm asking you to do is step back for a minute and not just look at yourself but the whole industry, your peers. There was a way, starting ... in the early '80s, that news on-camera people became stars.

Well, long before the 1980s, [news anchors] became stars: [Chet] Huntley, [David] Brinkley, beginning in the late 1950s; Walter Cronkite on through the '60s and '70s. The idea that news people as stars didn't emerge until the 1980s is not true.

But salaries took off astronomically.

Salaries took off astronomically; however, as early as the 1960s -- keeping in mind that a dollar in 1960 was not what a dollar was in 1980 -- the major anchors at major network newscasts were extremely well-paid. ... Now, it's true when we got to the '80s that the pay got to be better and, even discounting for inflation in 1960 dollars, got to be great. …

There's no question that it was not in the best interest of quality journalism [to have] this development of a star system. ... But it's easy to overgeneralize. You have to look at individual cases. There are people today who are making a lot of money and whose names are in the newspapers every day, who I know are coming in the morning and making telephone calls, that are trying very hard and succeed, to no small degree, to keep themselves connected to the news. Now, if your point is that it's easier now than it ever has been just to take the money, take the celebrityhood, take the glory -- if you want to put it that way -- and come in and read the news, it's easier to do that today than it's ever been. ...

So you're now in the anchor chair. It's the early '80s. ... Mr. Paley's still alive. The news organization is just moving along, and Larry Tisch buys the company. He was the white knight, the savior from Ted Turner. [Tell me about that period.]

Well, what an interesting period. And for anybody who cares about the history of American journalism, I think it is a good period to study. ...

By 1977, 60 Minutes was the talk of the television industry, not just the news industry, because here was a news program that was becoming a tremendous profit center. Before the development of 60 Minutes, even the very top of the network news division never thought of [the news] in terms of a profit center. ... People in the corporate entity began to say: "Wow, you know what? News can make money, and not only can it make money; it can make big money. And it can help us make even more money because by getting a ratings toehold early on Sunday night, the flow of that helps our entertainment programs later on." …

60 Minutes continued to be a big and growing proverbial cash cow, so much so that it was quickly decided, once 60 Minutes began to make this big money, that the entertainment division would get part of the money that 60 Minutes made. ... Instead of [putting] the money back into more correspondents, more viewers, better coverage, a large part of that is going to be put on the entertainment side, something I think a lot of people don't know. ...

Running parallel with this was a diminution of the power of the regulatory agencies -- that the power of the FCC, the Federal Communications Commission, over licenses and being able to hold networks and individual stations responsible for public service was quickly fading away.

So on the one [hand] you have, "Hey, news can make big money." On the other hand, any motivation we have to use some time just for public service, give it up for public service, is beginning to diminish. …

Then you get to the mid-80s, when Larry Tisch first came to CBS. And there are many people at CBS, including some of the best-known correspondents, who said: "This is what we need. This is the white knight. Here's a man with a lot of money, great personal wealth, who cares about the news, and this will be our platinum era." I didn't know what to believe, but I was very glad to hear this.

When Larry Tisch first came to CBS, he came for a lot of the right reasons. He told me that one of the reasons he came -- and I believed him -- was that there was an effort by Sen. Jesse Helms of North Carolina and others who didn't like CBS News because we had taken on [Sen. Joe] McCarthy, because we'd been out front in the civil rights coverage. ... CBS News had been born out of a desire to do independent and, yes, fiercely independent news when necessary, as a public service. But Sen. Helms and some other people had made public announcements that they wanted to buy CBS, and they wanted to buy CBS because they wanted to change the culture of CBS News. Larry Tisch took that talk seriously, and he thought that was not a good thing. ...

I think the biggest difficulty was -- and [Larry Tisch] said this in my presence once, when I was gently, maybe too gently, but trying to make the point that we need more bureaus not fewer bureaus, more reporters not fewer reporters -- he said, "Dan, your problem is you don't understand business. You're a good reporter, I'm glad you are with us, but you don't understand business." Well, the difficulty was Larry Tisch did understand business but he didn't understand this business, which is to say he certainly didn't understand the news business. ...

You're sitting in the anchor chair in the early '80s; you're watching this happen. Mark Fowler is head of the FCC; deregulation is going on; [there's] pressure to produce profits, because 60 Minutes is still number one or number two or number three, producing lots of money. When do you feel that you're in jeopardy? When did you feel you needed a white knight? What happened?

Well, what happened was that the Iran-Contra debacle had hit and was a big story, and the role of the then-Vice President George [H.W.] Bush in the Iran-Contra affair. Because he wanted to run for president in 1988, he rightly deemed that it was not in his best interest to spend very much time talking about Iran-Contra, because he'd had a role in it. His role was then, and to a certain extent now remains, murky, but what he said on the record about his role in Iran-Contra did not match the record as it developed.

So before the Iowa caucuses in 1988, we set up an interview with Vice President Bush, ... and he agreed to do the interview, but only if it were done live, which was not our preference; it was his. And in the interview he sought not to answer the questions, and I sought to press the questions, and it became a controversial interview. ...

The identification of you as anti-Bush, partisan -- the heat of the exchange is what lived on, not the content.

I disagree with that. Certainly for those who want to use it for their partisan political benefit, the heat of the exchange is what lives on, but I think it was part and parcel of my reputation as an independent and, when necessary, fiercely independent reporter. People who don't like that kind of reporting didn't like it before the Bush interview and wouldn't like it afterward. And those who do like it say, "Well, that's the kind of thing you expect Dan Rather to do." ...

Although there was an effort at the time and has been an effort ever since then to say, "Aha! You see, that demonstrates that Dan Rather is some bomb-throwing left-wing Bolshevik whatever," people as a whole don't buy that, even people who for one reason or another didn't watch the broadcast or didn't take to me as a television personality. The public is pretty good at figuring out what's going on -- what's really going on.

But I can see someone out there saying, "Fast-forward to Dan Rather and the presidential campaign with Bush's son." The Bush family in some ways reappear in your career. You don't always come out on top.

No. Two things: One, as a reporter, you don't always come out on top. It's in the nature of journalism. And certainly I haven't always come out on top. But I think this is very important for the public to understand: I don't think of it in those terms. I don't think in terms of coming out on top or coming out on bottom as a person. The story is what counts. ...

There certainly is a school of thought that says: "Don't make any waves. Don't think of yourself as a reporter. Don't cause any trouble. Don't get into any controversy. Don't dig [into] anything you're not supposed to dig into. And certainly don't tell tough truths about people in power, because it can be injurious to your career." Once you start thinking that way, once you let that get into your head, you're through as a reporter. You may remain a big-time television personality, you may be an anchor for a very long time, you may be well thought of and highly paid, but you're not going to be a reporter worthy of the name. ...

It's true that I did what I thought a reporter ought to do with President Bush I, as I'd done with every other politician I've ever met, from city hall up through the state legislature, and done with Democratic presidents as well as Republican presidents. There have been occasions when as a reporter it was my responsibility to ask tough questions, to dig deep on something. But that's much more a function that we've had two Bush presidents than anything else.

But both have categorized you -- if not they themselves, then through their emissaries and allies -- as their nemesis, the liberal Dan Rather who's out to do them in, the biased reporter who wants to destroy their careers.

When you cover politics, you're going to get this sort of thing, and when you're on television regularly, and you see yourself as a reporter as opposed to just being a presenter, and when you're as independent-minded as I am, you're going to get this thing. ...

People such as yourself say: "Well, wouldn't it have been smarter to think of yourself as anchor rather than a reporter? Wouldn't it have been smarter not to ask tough questions of power? Wouldn't it have been smarter not to reveal truths that people in power didn't want revealed?" Pursuing Iran-Contra with President Bush the first was asking tough questions of people in power that they didn't want to answer, and they always try to change the subject. And with the second President Bush, it would have been a whole lot easier not to work on 60 Minutes II, and a whole lot easier not to put yourself on the line with stories, but I chose to do it, and I'm not sorry that I chose to do it. ...

So why go to Mark Cuban, an unusual billionaire?

Well, I've gone to work for Mark Cuban because, one, he asked me; he offered me a job. But the main reason is that he offered me a job in which he said, "You will have complete, total, absolute editorial and creative control over what you do." Now, that's unique in my experience, and I think it's unique in electronic journalism. I don't know of anybody else who ever had it. I've never had that. And I became convinced that he meant it. He said: "The only thing I ask of you is have no fear. ... I want you to do what you want to do, and I'll back it." ... He owns the company. He doesn't have stockholders in the company. Also, he doesn't have to worry about demographics or ratings, which we haven't talked about much.

So why am I going there? I think I can do quality journalism with integrity.

Mark Cuban says that you'll be "unleashed."

Yes, he said that to me as well.

Did you feel leashed at CBS?

In some ways. I think anybody who works for a large corporation and in one of these large networks feels leashed to a degree. But I will say this: Nobody at any network has total, complete, absolute editorial and creative control over what he or she puts on the air. ...

In some ways we yearn for the golden years of the William Paleys and [RCA CEO and founder of NBC David] "General" Sarnoff and so on, but they had problems with their own moral compass from time to time. ... And going to work for a very wealthy person doesn't necessarily insulate you from problems in the future.

Not necessarily, but I like the chances. When it became apparent that I might have to leave CBS, and I asked myself, and my wife and other people asked me, "What do you want to do?," I said, "Well, I'm not sure the person is out there, but I'd like to find someone in this generation, the rough equivalent of Bill Paley when he first got in the radio business, or Ted Turner in the late 1970s, who had the vision." ... Not because they're perfect people -- if you're searching for the perfect person, you aren't going to find him -- but someone who's emotionally engaged in the responsibilities of trying to do quality journalism." [That's] what I was looking for, and I think I found him. ...

It raises the question, you know: He buys the Dallas Mavericks; he's bought Dan Rather.

Well, I think Dan Rather's record shows he doesn't sell and he can't be bought. I don't have any concerns about that right now, but it's true that I haven't been working where I'm working now for very long. But in one way, I'm old Texas, which is I judge a man a lot by the look in his eye and the shake of his hand. I like the look in Mark Cuban's eye, and I like the shake of his hand, and he has told me that I will have complete, absolute and total editorial and creative control, and I believe him. We'll talk in six months, a year, or in five years and see whether I'm right. ...

Your departure from CBS, and CBS obviously not being happy with the story in the end -- how were you treated?

I think I'll let other people answer that. I'm looking forward, moving on. It's a fair question, but I'm not going to answer that. ...

Were you a casualty in some ways? Because you really weren't involved in the details of the reporting of that story. ... You had faith in the people you worked with, but you really didn't know the facts of the story.

Well, some of that is true. But I think the most important thing, ... and this has been my creed for a long, long time, and it was forged in the fires of my early work with 60 Minutes and even before that when I was doing fieldwork, things such as the Watergate story, civil rights, and Vietnam: We're a team: ... the on-air correspondent, the producers, the reporters and the research people that he or she works with. ... And whatever happens, we go into the story together, we stick together when we're covering it, and we come out the other end together. It's so much a collaborative process; it is literally a team of people. I never want to be a person who says, "Oh, well, don't blame me; blame that person behind the tree."

We went into this as a team, and I tried very hard to hold us together as a team and find out the answers to a lot of questions about, had we done everything we could do and should do? That being my own belief, that I thought that we were all in this, CBS News was all in this together and that, yes, CBS was in it together, we came under tremendous pressure, we came under tremendous fire, and the heat weakens. I wasn't able to do what I'd hoped to do, which was continue to investigate the story, continue to work on the story.

We knew the content of the documents were correct. ... The information in there is correct and has been corroborated eight ways from Sunday. There's no doubt what is in those documents is true, absolutely accurate. And because it was absolutely accurate, the attacks centered on the form that it took. And nobody to this day has proven that the documents we presented were not what they purported to be. Our problem became, and remains, that we were not able to prove absolutely, without any shadow of any doubt, that they were what they purported to be. ...

[M]ost people have moved on. It's been a long time. And people who care about this, still care about it, have made up their minds. ... Unless additional information comes up, which it very well may, then history will judge how well or how badly we did the story.

But in terms of CBS, ... there were plans before the Bush story ever appeared for me to leave the Evening News at or about the time that I did. I'd been there 24 years, and I would have liked to have made 25, but I knew the preceding summer that that wasn't going to happen. They said they wanted to take CBS News in different directions, and consequent events have proven that they did want to take it in different directions. But promises were made and not kept. Contracts that had been written were not adhered to, and I didn't feel terrific about that. But then I've been so lucky and blessed that when you hit a bad place in the road, when bad things happen, or you say, "Ah, I really wish they'd done a little better on this or that," I have to remember how really lucky I've been. At base, I'm a reporter who got lucky, very, very lucky.

But you didn't resign, and you didn't get fired. The producer [and] the executive producer did. As happens often in this business, others -- not the on-camera person -- take the rap.

Well, if you think that I didn't "take the rap," as you put it, then I'd suggest you haven't been reading the papers. I stood by every person who was involved with that, stood right by them and still stand by them. Didn't give up on anybody. And the company made its decisions. What would it help for me to do that?

... Here I have to be transparent. I was at CBS News. I tried to do a story that I couldn't get on the air, initially anyway, and the people around me saluted the company. [They] said: "Get on with your business. Do something else." And even when the story came out that we hadn't done the story, there was a lot of mixed reaction inside the company about the whole situation. And it forces me to ask you, what goes on? ... It was my experience in [a similar] situation that it was a lot of running for cover.

... Certainly when the pressure gets on, when the heat gets on, when you're taking flak, one of the inevitable things that happens is that the envy, jealousy, dissatisfaction of seeing somebody else "get it," if you will, ... that gets set loose. ...

When the heat gets on, there are certain people who want to take advantage of it, your disappointment, even inside. And, you know, I have actually worked for a living when I was younger; I worked in the oil fields and on the pipeline gang. It's present there; it's present in every newsroom. So that's a factor in things. ...

[And] then there are those who said, "What you need to do is cut yourself loose from all of these other people, these people you work with." And I chose not to do that. I chose to stick with each one of them. And when I was asked before the commission that the company hired to investigate this, and I answered the question, I told them that if I had a story of this magnitude to do this afternoon, I'd be very happy to go and do it with the same people that I did this story with. ...

![News War [site home page]](../art/p_title.gif)