- Some highlights from this interview

- Being a black journalist in the 1960s

- The pros and cons of confidential sources

- How a federal shield law could hurt the press

- Why journalists aren't heroes anymore

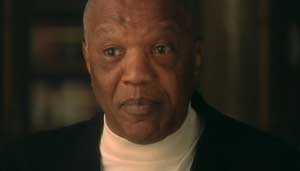

Caldwell was a reporter with The New York Times in the late 1960s when he was posted in San Francisco to report on the Black Panthers. When the FBI asked him to keep them informed about the Panthers' plans, he refused and was prosecuted. His case eventually went all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled that reporters did not have the right to withhold information about their sources. Ultimately, Caldwell was never called to testify. This is the edited transcript of an interview conducted on July 6, 2006.

Why did the FBI want you to testify about the Black Panthers?

Well, at that time, I thought they just wanted me to be a spy, someone on the inside [who] could tell them what was going on. ... Now I believe that was very naive. I think they wanted to remove the reporters from covering the Panthers. They wanted to isolate them [the Panthers] from the press. For one reason, the Panthers were very effective in getting their message across in the media. They were really genius at it.

Secondly is I think the FBI did not want reporters there, because sooner or later, either through good reporting or dumb luck, we would have stumbled onto their [the FBI's] law breaking. And there was huge law breaking under the COINTEL [counterintelligence] program at that time.

... The FBI said that the Panthers had made a threat to the President. I did have the quotes about that in my story. ... The Panthers were saying, "And we recognize the government is being oppressive, and we have our duty -- obligation -- to bear arms against the government." ...

What exactly were you reporting on when you were covering them?

The Panthers really first emerged in late '66. By 1968 they had begun to attract a lot of national attention. Now, mind you, in '68, another huge event happened: [That] was the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. And Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination ended with riots, [more] violent riots in the country maybe than ever before. But it was an escalation of these riots that had begun in black America in 1964. ... And then came this group of very young people in their militaristic uniforms, black berets, black leather jackets. But most of all, they were embracing the gun. ... There was genuine concern in America. ...

By the time the Panthers began to emerge, there was this serious concern in a lot of places, particularly in these newsrooms, that black Americans were headed toward some kind of violent confrontation with the government. ...

“Freedom of the press is always in danger, ... because it's pretty awesome to say ... we have the power to do this and publish this and that. It disturbs, aggravates, intimidates people in high places, people who have power.”

I went to California in the fall of 1968, and really, most of my primary job, almost my entire job for that period as a national correspondent with The New York Times was to cover the Black Panther Party. You could say I lived with the party members through the next two years. ... My editor wanted me to get on the inside, tell us where they going, what does this mean?

And how did [the FBI] come to be involved with you in your reporting on the Panthers? ...

If you go back, the very first story that I wrote about the Black Panthers was about guns. ... I thought it was my great reporting. Later I realized they wanted me to see the guns, because they knew if I saw this that I would print it in my story and it would be published in The New York Times, and then everybody in the country would know that they were prepared, on some level, to back up what they were talking about.

When I wrote the first story, I came back to New York, and now I believe somebody in the newspaper called the FBI and told them that I had come back, because I was at my desk five minutes, and the receptionist called and said, "There's two gentlemen out here to see you." I go out; it's two agents from the FBI. They want to know more about these guns that I wrote about. They want to know more information. I told them, "Everything I have is in the newspaper." They said, "That's not good enough," and they challenged me. ...

One of the things that people forget, in 1968, there was this Kerner [Commission] Report. President Johnson had created a commission to look into the causes of these riots that were sweeping black America at that time. One of the most astounding things is what Kerner came back with and said a big part of the blame is the institution of the news media. Not only are they not telling Americans what is happening in this country; even if they wanted to tell, they couldn't, because they don't have the staffs to do it -- their staffs are all white. … It was a truly damning indictment of the media. …

... This huge story was developing. [The news media] couldn't cover it, so they began snatching black reporters from everywhere. ... The Los Angeles Times had a guy in the sales, ads departments, and he's the only black in the building; they sent him out to Watts. We used to call those battlefield commissions. They'd send you right on out. …

We would all get to know each other, because we would all see the other black journalists at riots or at the NAACP [National Association for the Advancement of Colored People], Urban League, black organization conventions. … When I set foot on the ground, California, I checked in with The New York Times bureau chief, Wallace Turner, and everybody. But I next went to see a fellow named Rush Greenlee, who was the only black staffer at the San Francisco Examiner. I'd met him at a convention. …

He hooked me up so tight that, on the very first night, I'm over in Eldridge and Kathleen Cleaver's house sitting in the living room, getting close to what I'm looking for. That was the hookup that eventually led me to see the weaponry that I could write about in the newspaper. So the black journalists, we had something going on that our editors really were not aware of. ...

How did it get to the point where the FBI came to you and said, "We want [your tapes and notes]"?

There came a period, after I was covering the Panthers maybe about 12, 14, 16 months -- I'm not sure -- where the FBI called me and asked if I would have regular meetings informally with agents. They said: "We know that you're over there all the time and you're seeing what's happening, and you're all around with them. We'd like you just to tell us what's going on, be our eyes and ears on the inside."

I told them of course I couldn't do that; "I can't even have this conversation with you." But they persisted in it. They would call The New York Times bureau almost every day in San Francisco. ... Then one day they told this woman ... who was answering the phone: "Tell Earl Caldwell we're not playing with him. He doesn't want to tell it to us, he doesn't want to talk to us, he can tell it in court." This was like on a Friday. On a Monday, they ... came back with a subpoena for me to appear before a federal grand jury, and they wanted all of my notebooks and tape recordings and anything else I had accumulated over that period, about 16 months of reporting on the Black Panthers.

And you said no?

Oh, absolutely. ... I began to create a little file in the back of The New York Times office, a private file, apart from The New York Times file. ... stuff that I considered to be very sensitive, and I don't want anyone messing with it. ... I had to destroy a lot of this [very sensitive] material before the agent came back, before the marshal came back with the subpoena. ...

Why did you feel like you had to destroy material?

If ... it wound up in the hands of the FBI, people were going to say to me, "That was the intention all along." There was a virtual war going on by this time, escalating between the Black Panthers and the authorities. ...

Did [you] even consider the idea of turning over your material?

No, I never would have done that. It wasn't even possible to think about doing that. ... There was no way that we as a generation of black journalists -- we were not going to do that.

You said that [the Panthers] were aware of the value of public relations and that they wanted to get information to the Times. Did you ever worry that you were being spun by the Panthers or that they were using you?

Oh, there was no question. Everybody uses a reporter. That's what happens. The police want to use you; the people want to use you. ... Of course the Panthers wanted to use me. But the things that they wanted to use me [for] were part of the stories that I wanted to tell. ... I'd meet them maybe 2:00 in the morning. We'd go off to some church, and there would be guys and women -- they'd be in there preparing this breakfast for these guys. ... To see what they were doing and to get to know these people was an awesome story to tell. I was into it with all that I had in me. ...

So you were also subpoenaed to appear before the grand jury.

Yes.

How did you deal with that?

Well, when I was subpoenaed, the first thing is, I had my little group of black journalists, the Bay Area Black Journalists Association. But we also had the New York Association of Black Journalists. Everybody thought Earl Caldwell was out there by himself, because the subpoena was very carefully worded. Didn't mention New York Times at all. It was just Earl Caldwell, the reporter. Very vulnerable.

The New York Times hired a law firm. The San Francisco paper had this big front-page story about this prestigious law firm, ... Pillsbury, Madison and Sutro in San Francisco. I'll never forget, I went down there to see them, and they told me -- this guy named John Bates -- he told me, he said, "We've got a tremendous problem out here of law and order." He said, "The first thing I want you to do is bring all of your material on the Black Panthers down here so that we can go through it." He said, "Because some of it surely should be going to the FBI." Right away I knew those lawyers weren't going to work. ...

So I went to meet off with my black journalists, and we're running around talking about lawyers. ... But the New York Association of Black Journalists called Black Perspective; there was a fellow there who was the president named Ernest Dunbar, and he had connections with the Legal Defense Fund -- then it was known as the NAACP Legal Defense Fund -- and they knew a constitutional lawyer whose name was Anthony Amsterdam who was famous among black people in that circle because he was the foremost lawyer in arguing against the death penalty. ... They contacted him, and they called me in California and said, "Go down to Stanford University and see Anthony Amsterdam." ...

It was about midnight when we went down -- about four, five of us in an old car -- we went down to [Palo Alto], and we met this guy. Brilliant man. He was waiting for us. He said, "I've already studied the case; I've already looked into it." I'm up there telling him, "Well, I'm not going to do it," and he said to me, "You have a legal right to refuse." That was awesome. He also said to me, "Don't you even come to that meeting tomorrow morning." We were going to have a meeting the next day of Pillsbury, Madison, Sutro lawyers; the vice president for the Times would come out and everything. He tells me, "Don't you even show up." He said, "I'll tell them that I'm representing you." ...

Did you ever feel conflicted at all that maybe these gentlemen [in the Black Panther Party] were dangerous ...?

First off is, mind you, these are black people arguing for black rights. I mean, it's just like Martin Luther King Jr. He's up on that platform talking about the rights of black people. I can't separate myself from that because I'm black, and he's talking about my rights. I'm a reporter. But reporters are human beings, so we're faced with these same things every day.

What I was concerned about was this: The FBI was trying to force me to be a spy. They knew that was wrong, and I knew it was wrong. That first day when they came to New York Times, they wanted to know about the guns. They told me that if this would have been the Minutemen or some other organization, they'd be in there talking to white reporters, and the white reporters would cooperate. And I don't know. I don't know. But I was serious about being a reporter. ...

Now, how did the legal defense proceed from there?

… Tony Amsterdam was brilliant in his arguments. ... His position was that I shouldn't have to appear before the grand jury. ... He argued that the First Amendment not only protects sources and information, but also it protects the reporting process. He said that all the information I had that wasn't confidential was already in the newspaper. And he had a lot of my stories. He ... talked about how the history of the business, the way the black journalists came in, ... how we could bring back an answer and tell America about these questions that were so large at that time. So [Amsterdam was] really looking at our role -- what we were doing, what we were producing.

The United States Court of Appeals, they found me in contempt. They said everybody has to go to the grand jury and that they would give me a protective order enough to give up any confidential information. But they said, "You must appear; everyone must appear." ... The government argued I should go to jail that day. ... Amsterdam argued that I should be allowed to remain free until we were going to appeal.

As it happened, The New York Times wrote an editorial, said this was a great victory because the court had ruled that I didn't have to give any confidential information. But I had to appear, ... and for me, that was what I could not do. There was no way I could go before a secret proceeding that was investigating the Black Panthers and then come back. ...

Amsterdam told me that I didn't have to go. When we appealed, I remember just as plain as anything, June 16, 1970, the late managing editor of The New York Times, Abe Rosenthal, put a memorandum on the bulletin board here and said that the issue in this case is authentication. That's all that it is. They're not asking Caldwell. He's got a protective order. He doesn't have to give up any confidential information. He doesn't have to reveal anything that he's promised his sources he wouldn't reveal. … But he must appear before the grand jury, as [does] every citizen. And he said that New York Times would not support me in this case. They had to step away. Said any time a reporter refuses to authenticate his or her story, said, "We have to step away from that because it would cast doubts about the integrity of New York Times stories."

Now, I don't know where they came up with this issue of authentication being the issue. That was not the issue. They didn't know what the prosecutor was going to ask me. But that's what they came up with. ...

On June the 30th, two weeks later, almost every black journalist in the country, we slipped off from our jobs -- we went to Jefferson City, Mo. We had a meeting, a conference, to decide what we're going to do. Of course we appealed this case. The black journalists ... acquainted people all over with these issues, especially black people, and why I couldn't go before the grand jury.

The next thing that happened was [Amsterdam] took this case without The New York Times to the United States Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit. I think [the Times] did come in with the brief at the last minute in front of the court. But even that, they were asking for less than what we were asking for. Tony Amsterdam was arguing that you're going to destroy this reporter, because you've already said in the protective order that he doesn't have to give up any confidential information; he doesn't have to release sources. So what you're saying is that he has to go down here for what would be a barren performance, and he would be destroyed in the eyes of his sources. Not only him, but how many other reporters would be hurt? He argued that the First Amendment, this is precisely what it protects -- not just information, but the process. ... He talked about how reporters could bring back and answer and tell America about these questions that were so large at that time.

We won a unanimous decision from the United States Court of Appeals. We're in the Fox Plaza Building in San Francisco, drinking champagne. This was a tremendous victory, because when this case was going on, ... [Times lawyer James Goodale] put his finger in my face and said: "What's going to happen? There's no law in this area. The government assumes that it has rights, and we -- the institution of the news media -- assume we have rights. But we don't want any settled law." He's telling me, "What you're going to do is get some bad law written, and reporters [are] going to suffer for years." …

[The 9th Circuit decision] was like, on a Friday. On a Monday, the government appealed it to the Supreme Court. And then we really got hurt. ... [The New York Times] didn't have any major lawyers; they didn't have any major editors; they didn't have any important people from this institution. It wasn't the way it was with Judith Miller, where they were all there in support. Earl Caldwell was there by himself with Tony Amsterdam. ...

So the Supreme Court rules against you. [Editor's Note: Caldwell's case was combined with two others before the court and the case became known as Branzburg v. Hayes.]

Yes. They stole our victory. We had a victory. This Court of Appeals ruled that I did not have to go before the grand jury. No court anywhere had ever said that there is a reporter's right and there are circumstances where the reporter does not have to appear before the grand jury. ...

Then after [the Supreme Court decision], Jim Goodale took this defeat and spun his opinion on it about reporter's privilege.

Yes, he did. ... I'm not a lawyer, so I can't really say, but I do know this: In the difficult time, it was Tony Amsterdam who framed the arguments. It was Tony Amsterdam in the Legal Defense Fund that provided the wherewithal, and that until they start[ed] messing with us, we prevailed. That's clear. …

Branzburg is really Caldwell. When the government appealed this case to the Supreme Court, they folded two other cases into it. But those cases were materially different. Branzburg, he's a reporter; I support him; I think he was right. I think he had a right to keep his sources confidential. But the fact of the matter is [the] Branzburg case at its center involved illegal conduct -- somebody manufacturing drugs and hashish and some stuff in downtown Louisville. ... Caldwell case had no illegal activity. It's a reporter trying to do his job and the government messing with that reporter.

Tony Amsterdam told me after this case was over -- I always like this story -- he said it was the easiest case he ever had to argue at the Supreme Court. He said, "Because all you had to do was read the stories that Earl Caldwell wrote that were published in The New York Times, and then you would know why it's important for the government to leave him alone and let him do his work." …

What are the stakes for reporters when they can't promise confidentiality to a source?

... Most reporters don't want to offer people confidentiality, because the minute you say any of that kind of stuff, you're hurting yourself. But sometimes you have to do it, especially when you're trying to get in; especially when you're trying to get people to know you, to trust you, to let you in, and especially when it's a very sensitive subject. …

With myself and the Black Panthers, [I didn't write] some Panthers were in a little meeting one night and said, "We've got to overthrow the government." The leading Panther who wasn't in prison at that time, David Hilliard, said these things. But I quoted David Hilliard as saying them. That's why they mean something. I do believe that the anonymous sources really get us into a lot of trouble. People say, "Well, you have to have anonymous sources," but to me, a lot of times, if you can't tell your sources, then it takes away from the information. ...

What's your reaction now when we hear members of this administration saying that The New York Times and others are damaging national security by revealing public programs?

It's laughable. Of course they say that. It's laughable for them to say now that a newspaper is going against national security by disclosing some program that they're operating. Why are they saying this? Because it's the most secret administration in probably the history of the country. … But the newspaper didn't make this up. Somebody in this administration felt it was so important that they came to the newspaper and said, "This is something you ought to know about." …

The press, we have this other responsibility to stand alone and to look and see for ourselves, for us to know and to say, not just to know and play "I've got a secret," but for us to know and to tell. ...

This is one of the reasons I really, truly believe the hell with the federal shield law, with the government sanctioning us. You say: "Well, it's easy for you to say. You're not a reporter out here now. You're not the one that's going to jail." But I believe that this is what's going to have to happen. We've got to have reporters that are ready to stand up and go to jail -- and many of them are -- because I believe that when the public can truly see exactly what is involved, that they would be on the side of the reporters. ...

But you don't believe in a federal shield law?

No, I don't believe in a federal shield law. I believe our rights are constitutional. I'm a founding member of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. Every day I think I should resign because they're one of the leading advocates of going to the Congress and asking them to legitimatize us. They can't legitimatize us; our rights are constitutional, and if they're not constitutional, they don't exist. ...

If you say to this legislature, "Please, Mr. Legislator, give us some rights," they love you today. Say, "Yes, absolutely." They hate you tomorrow -- they say, "Take it away." Or the first thing they have to do, which to me is the most dangerous of all, they've got to define who is a reporter, who is a journalist. How can you do that? Simply because you work for this big corporation, does that make you more valid than someone that's working for a little weekly out in somewhere, or a person that's at home putting it out on the Internet? All these are important pieces. I believe it's constitutional. [If] it's not constitutional, they don't exist. ...

The public is not on our side, and I think that in the news media, one of the things is you have to have the public on your side. This is what the biggest difference is now for me. When we ended up going against the Black Panthers -- and in that period, the people used to be happy to see us coming as reporters, because they actually believe that we were going to be a part of telling some truth; that there were situations where I'd see us come onto a scene and people would actually applaud us. We were hero figures. You might say it's part of the last great time to be a reporter, especially a newspaperman, in America. But that is what's different. We don't have that kind of trust now. People don't hold us in that high regard. ...

Why is it that journalists aren't heroes anymore?

I truly believe that one part of it has to do with that anonymous sources thing. ... Also, I think another thing is the technology. ... The separation now is not as great as it was. I came in a time when we had these huge, larger-than-life figures. A fellow that befriended me, became a guru for me, was the late [CBS president] Fred Friendly. He was the first person to really talk to me about the First Amendment and about the responsibility of the media and what we could do for good if we weren't so obsessed with money. And you know, Fred Friendly, ... after building probably the greatest television news organization ever now, ... he got ran out. But we've been going bit by bit by bit, slipping back since then.

Now we're at one of those points where -- I hate to put it like this -- but this is where I say for some journalist to have to go to jail now, it's not the worst thing to happen, because you're in a fight for what you believe in. And I think the public has to be able to look and see and to understand what you need to be effective in doing your job, and then seeing results that they can buy into of your work. It's not as simple as it used to be. ...

Is freedom of the press in danger now?

Freedom of the press is always in danger, and as well it should be. I mean, [it's] understandable, because it's pretty awesome to say we can go in, we can do this, we can do that. We have the power to do this and publish this and that. It disturbs, aggravates, intimidates people in high places, people who have power. But it's necessary. And when you really think about it, it's one of those things that's in the Constitution. ...

Everybody can't go to the trial down at the courthouse. They say you're entitled to a public trial. This is one of your rights; you're entitled to it. But there's not enough seats in the courtroom for everybody to get there. That's why we say we're going to set these five seats aside for the reporters, because we truly represent the public; because the public can't go [to] these places, can't know all these things. …

In America, we've had a great tradition of journalism. ... It used to be drunks in the newsroom. There would be yellow journalism and all these kind of things. But no, we're not going to do that anymore. We're not going to take money; you're not going to take any gifts; you're not going to do this. We're going to be not making anything up. ... And we got to a very high place. …

But something happened, and we got on the other side, and we've been going down the other side. ... I believe in some ways, we began to compromise ourselves over money, and it's causing trouble, problems for us that are great now. ...

I said I used to believe in the power of the press. Now, I see that there's an awful lot of weakness in there, that they're afraid to do things, afraid to say things, afraid to publish things. ... I think a part of it also has to do with the finances. ... With the largest news organizations in the country, ... the big fights internally are about profits. …

You can't have it both ways. You cannot say that we're not going to give people this solid information about things they need to know about and then expect people to have trust in you and to support you. ... One of the reasons why there are so many subpoenas now is because people know the media is weak, and you can kick them in the behind, and there's no penalty to it. ... But a part of it has to do with because these news organizations [are] timid on a lot of areas where they ought not be.

![News War [site home page]](../art/p_title.gif)