- Some highlights from this interview

- Why has classification increased under the Bush administration?

- How is unclassified material being kept secret?

- The state secrets privilege

- Who decides what's classified?

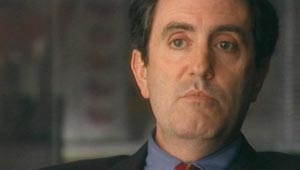

Aftergood directs the Federation of American Scientists' Project on Government Secrecy; in 1997, he won a lawsuit against the CIA to declassify the federal intelligence budget. This is the edited transcript of an interview conducted on June 14, 2006.

... Are you seeing changes in how [the Bush administration] handles Freedom of Information Act [FOIA] requests?

There are a few different things going on. Wait times have become longer; backlogs of requests have grown; the standards under which information is released have in some cases become more restrictive. In other words, information that might have been released several years ago now gets withheld. ...

A lot of these changes were encapsulated in a policy memorandum that was issued by then-Attorney General John Ashcroft in October of 2001. What Attorney General Ashcroft said is that the prior policy, which encouraged disclosure of information unless some foreseeable harm would result, that policy was being overturned in favor of withholding information whenever there was a legal basis to do so. So the whole orientation of the FOIA program was in a sense reversed. Instead of saying, "Release whenever you can," the policy became, "Withhold whenever you have a legal argument to justify."

One can detect the influence of that policy in how FOIA requests are handled. There are all kinds of things that once would have been released or were released that now get withheld under FOIA, and it's disturbing. ...

[How do you balance a free press and national security during wartime?]

A vigorous and vital press is even more important in times of national crisis, including war, than it is in times of tranquility. When the nation faces urgent decisions of whether to persist in military activity, whether to initiate new pre-emptive strikes, whether to alter our energy policies, how to deal with questions of foreign aid, disaster relief, all of these things, we need not just two sides of an issue; we need a dozen sides of each issue. The only way we get that is by going beyond the official storyline to enrich it with multiple perspectives from multiple sources. What has happened is that new obstacles have been erected in the path of journalists who are trying to get those alternate sources. ...

It's been said that information is the oxygen of democracy, and when you cut back on it, the quality of our democratic life suffers. Sure the press has problems, and the press has to deal with them one way or another. But they're not only the press' problems. They're the problems of all of us who are concerned citizens, and if we don't find a way to reinvigorate public access to information, then we will all pay the price. ...

It is through the press that most of us get our information. Most Americans will never file a Freedom of Information Act request, and there's no reason that they should. We all have multiple conduits for information and all kinds of ways to educate ourselves. But what's happening is that all of those conduits are being constricted and constrained by official secrecy, and it is really having an impact on the quality of our deliberation. ...

[Have classification levels changed?]

There's no doubt that classification activity has accelerated in the course of the Bush administration. Why is that? There are several reasons, some of them good, some of them less good.

“There are all kinds of things that once would have been released or were released that now get withheld under FOIA, and it's disturbing.”

For one thing, we are in a heightened security environment post-9/11, and we have large military operations actively under way right now. Whenever that's the case, there's going to be increased secrecy. I think no one doubts the need for increased classification in time of war, but that's not the whole explanation.

There is also an increased willingness to exercise classification authority for silly reasons or no good reason at all. A few years ago I sued the Central Intelligence Agency under the Freedom of Information Act seeking declassification of the intelligence budget total, one number. This was in 1997. And they disclosed the number. It was $26.6 billion at the time for the entire intelligence community.

A few years later I asked them: "What was the total intelligence budget for 50 years earlier? What was the budget for 1947 and 1957 and 1967?" And they said, "Oh, no, we can't tell you that; that's classified." So you have a bizarre situation in which the budget total, the intelligence budget for 1997 is declassified. It didn't leak; it was officially declassified. But the budget for 10 and 20 and 30 and 50 years earlier is still classified. Why? Because the CIA says so. It makes no sense at all, but it is the policy of our government. ...

[What are the classification designations?]

Most of the time when we talk about secrecy, we're talking about classified information, which is information that is officially marked according to presidential direction as either "Confidential" or "Secret" or "Top Secret." But above and beyond the classification system, there are a whole series of controls, restrictions on unclassified information.

There are markings such as "For Official Use Only" or "Sensitive But Unclassified" or "Limited Official Use." There are literally dozens of such things which are used to restrict the distribution of unclassified information, and this is something that has really spiraled out of control in recent years.

According to one estimate, there are more than 60 different restrictions on unclassified information that have been used. It's not simply that it impedes access by the press to information, but it also ties the government up in knots, because if one agency has information that it says is "For Official Use Only," but another agency has information that it says is for "Limited Official Use," can they exchange information and expect that their information will receive the same level of security that it does in their own [agency]?

It's a nightmare. Agencies are tying themselves up in knots with these sort of ad hoc restrictions that have been invented. It's a very serious problem, because most classified information, there's at least a shadow of a reason why it's classified. But in many cases, something that is marked "For Official Use Only," that's essentially a made-up kind of restriction, and what it does is to block or at least to slow down the dissemination of information inside and outside of the government.

… I'm trying to report a story; I come across a document like that. What happens?

When one of these designations is used to control unclassified information, its impact is a little bit unpredictable. Some officials will say, "Oh, if it's not classified, I don't care; I'll give it to you." That's great from a reporter's point of view.

But others will say: "It's 'For Official Use Only.' It has this designation on it. I can't give it to you, even though it's unclassified." That turns out to be quite a problem, because it amounts to a kind of de facto classification for unclassified information, and the upshot is that a lot of information that might otherwise be disclosed gets held up.

Now, simply marking a document "For Official Use Only" does not by itself change your legal rights under the Freedom of Information Act. You could still file [a request] for information that bears such a marking. But the point is that you actually have to request it formally. You have to go through the motions. Simply asking for the information is no longer enough. And that can mean the difference between getting a story and giving up, because it will takes weeks or months to get the record. It's a big problem.

Who's making these designations? Are they trained and qualified to be designating?

In most cases, any employee of the government can stamp something "For Official Use Only." At least in the classification system, the formal classification system, you are supposed to have official presidential delegation of authority in order to create new units of classified information. But anyone can write "For Official Use Only" on a document and effectively keep it out of the public domain on a timely basis. ...

How many documents are we talking about now being subject to these designations?

This problem of controls on unclassified information is a much bigger problem than the problem of classification itself, which itself is a very big problem. But the volume of information, unclassified information that is somehow restricted, is vastly bigger than the world of classified information, and no one really has an idea of just how big it might be.

I can tell you that there are many, many more government employees who are authorized to create, to impose these designations on unclassified information than there are who can classify records. And they do. It's much easier to do. There are no restrictions; there's no oversight. It's a way of restricting the flow of information that is much more consequential, I think, than the classification system.

... Are we talking about millions of documents? Are we talking about billions of documents? What's the paper load here?

It's impossible to say. And keep in mind that increasingly, documents are not paper records, but are soft-copy electronic records, and entire databases and software systems will be designated as off-limits. So it can easily be many millions of records.

Again, there are legitimate reasons why unclassified information might not be and should not be publicly available. People's Social Security numbers are not classified, but they are sensitive, and they should be withheld. There's all kinds of privacy information.

There may be proprietary information. There may be security information. The workings of an alarm system at a government installation may not be classified, but it's understandable that they would be withheld. The problem is not the existence of such controls, but the way that they have proliferated and mushroomed, and the way that they are being imposed indiscriminately. ...

[Tell me about the Information Security Oversight Office's study.]

The Information Security Oversight Office is an organization within the federal government that is responsible for overseeing classification and declassification activity throughout the government. Among their responsibilities, they produce a report annually which tabulates agency statistics on how much they have classified, how much they have declassified. They provide one of the few objective, statistical measures of changes in classification policy.

Among other things, they have shown record growth in classification activity in this administration. The volume of new classified material has literally reached a record high in the Bush administration. Meanwhile, declassification activity, which was at record-high levels in the 1990s, has tapered off considerably. Records still do get declassified, but much more slowly than in the recent past.

I believe they also found that there was a lot of improper classification and designation happening, that things were not being properly marked. ...

The Information Security Oversight Office ... did a study of records at the National Archives that had been withdrawn from the public stacks, reclassified. What they found was that at least a third of those records should not have been withdrawn. They were properly public information, and yet agencies considered them classified and removed them from public access.

If you take this study and look at it as a benchmark of the system as a whole, it suggests that at least one-third and probably more of all of the records that agencies classify should not be classified, that there's no valid reason for them to be withheld from the public. That's an astonishing and alarming statistic, because it suggests that just a huge fraction of official secrecy is not justified on national security grounds.

How would this ever get rectified? What would have to happen?

How will this ever get rectified? It won't get rectified without a will to correct it on the part of agency heads themselves. It's not enough for reporters or even for members of the public to say, "This is unacceptable."

It will change when the senior leadership at the agency levels says, "We are not going to classify information that doesn't need to be classified." When they make that commitment and instruct their agencies to follow through, then it will happen. It won't happen until then.

When will they make such a statement? They will make such a statement when the top of the administration, the president and the senior leadership, say, "Classification is only to be used for legitimate national security reasons and not for any other reason." Until that signal comes from the top of the administration, we're not going to see a change.

Describe [the state secrets privilege] and how it's used under this administration.

The state secrets privilege is a privilege of the executive branch which permits it to block someone who is suing a government agency from obtaining information that is subject to the privilege. That's a roundabout way of saying that the state secrets privilege enables a government agency to withhold information from a litigant who is suing the government.

It is recognized by the courts that there are certain types of information that, if disclosed, would jeopardize national security, and the court permits a government agency to assert the privilege if it believes it is warranted. Now, what has happened in recent years is that the state secrets privilege is being invoked more and more frequently to block litigation.

It is not being used to prevent the disclosure of individual facts A, B or C, but instead to shut down entire proceedings. People who sue the government -- whether they are whistleblowers or they claim that they have suffered an injustice of one kind or another or even patent claims, patent-infringement claims -- a wide variety of cases have in effect been thrown out of court when the government invokes the state secrets privilege, as it has done increasingly in recent years. It is an alarming way of short-circuiting the judicial process, and not simply protecting one or two facts, but effectively closing the courthouse doors to cases that the government does not want to see tried.

Do you have an example of [the] state secrets privilege being used?

One of the most shocking cases to me in which the state secrets privilege was invoked was the case of Khaled al-Masri, who was allegedly kidnapped by the Central Intelligence Agency and alleges that he was subjected to illegal detention and torture. Now, he filed suit against the Central Intelligence Agency, and the CIA said: "State secrets. This case cannot go forward because state secrets are involved."

As a consequence, this fellow, al-Masri, could not get his day in court. The judge said that it may well be that his claims, his allegations, are true; it may well be that he was tortured. But he will not be permitted to argue his case in court or to get a ruling on his allegations, because the CIA says state secrets are involved.

State secrets were well served by this case. Justice was explicitly not served. Justice was not done here. That, to me, is shocking.

[Take us through what happened with the Associated Press' attempt to cover Guantanamo.]

Yeah. In the course of covering Guantanamo Bay and the situation of the hundreds of detainees held there, the Associated Press was forced to file a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit in order to gain access to the information it needed to report on the story. The government took the peculiar position that it could not disclose information about the detainees because their personal privacy would be compromised if it did so.

In the end, of course, much of what we know about Guantanamo Bay was disclosed thanks to that lawsuit. The government eventually conceded that such information could and should be disclosed. That is a great tribute to the power of the Freedom of Information Act. It's also, one could say, a disgrace that it was necessary to sue the government in order to gain access to such information. ...

![News War [site home page]](../art/p_title.gif)