After Hurricanes Katrina and Rita devastated the Gulf Coast in the summer of 2005, the U.S. Congress appropriated an unprecedented $126.4 billion for relief, recovery and rebuilding efforts. While it seemed that sweat equity and billions of federal dollars would have been sufficient to bring back New Orleans, years later, much of the money committed to its residents had yet to reach them.

In The Old Man and the Storm, FRONTLINE correspondent and filmmaker June Cross journeys with the Gettridge family of New Orleans for 18 months as they endure devastation, political turmoil and a painstakingly slow bureaucratic process to rebuild their homes and their lives.

Cross meets 82-year-old Herbert Gettridge during the 2006 Mardi Gras celebration. He is skipping the festivities, choosing instead to clear debris from his front lawn. Not one of his neighbors for blocks has returned, and he is without electricity, gas or water.

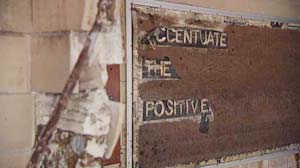

A master plasterer and experienced builder, Gettridge is working to get the house in good enough shape for his wife, Lydia, who is staying with their daughter in Wisconsin, to return. "It took me too long, and I worked too hard to build what I had here to just pick up and leave like that," Gettridge tells Cross.

Herbert and Lydia Gettridge raised nine children in the mostly African American neighborhood of the Lower Ninth Ward. Their house, which Mr. Gettridge built on land he purchased in 1943, took on 10 feet of water when the levees breached. Five of the Gettridge children also owned homes in New Orleans. They all lost everything. While some of the Gettridge children and grandchildren have decided not to return to New Orleans, three of them -- Leonard, Ronald and Gale -- have forged ahead with gutting and rebuilding their homes, even as the future of the city remains uncertain.

Over the year and a half that Cross follows him, Mr. Gettridge battles with the city to get his electricity turned on. He worries about bringing his wife, Lydia, who is in poor health, back to a city with a broken health care system. Dealing with insurance underpayments and skyrocketing rates, Mr. Gettridge navigates the bureaucracy and waits for federal rebuilding money promised through the state-run Road Home homeowner assistance program.

By the winter of 2007, 18 months after the flood, Herbert Gettridge and more than 100,000 other Louisiana homeowners had applied for money from the Road Home program, but fewer than 500 had received a check. Application rules seemed to change monthly as federal agencies argued over regulations. At one point, the whole program seemed in jeopardy after the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) told the state that each application required an environmental impact review.

Additionally, the Road Home program, relying on FEMA's statistics, underestimated the amount of help needed, leading to a $2.9 billion shortfall. Donald Powell, the former federal coordinator of Gulf Coast Rebuilding, tells FRONTLINE, "That shortfall ... was based upon expanding the program unilaterally by the state to include wind [damage] versus just those homes that were destroyed by the water." Louisiana Recovery Authority's Sean Reilly replies: "It came as a bit of a surprise. The Road Home had been in design and implementation for almost 15 months, and all of the language in the HUD application said that damage from whatever source, whatever cause was going to be covered."

Meanwhile, ICF International, the company then-Louisiana Gov. Kathleen Blanco had chosen to run the Road Home program, revealed in public filings that more than $2 million in bonuses had been awarded to its leadership team. ICF declined to be interviewed, but in an e-mail to FRONTLINE, the company defended its overall performance and justified those bonuses by saying that its executives get paid less than the average industry standard.

In June 2008, nearly three years after Katrina, Herbert Gettridge brought his wife home to New Orleans. Returning to a place that was decidedly different in structure and in spirit, Lydia Gettridge's homecoming was bittersweet. By sheer force of will and without the hundreds of millions of dollars promised to Louisiana, her husband had managed to rebuild their home of more than 65 years. But the Gettridge home remains a lonely monument.

Would he do it over again? "I'm kind of skeptical about that now," Herbert Gettridge replies. "Once upon a time, I could answer that question in a split second for you; I can't do that now."