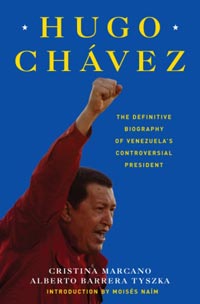

From the biography, Hugo Chávez, by Alberto Barrera and Cristina Marcano (Random House, 2007). Reprinted with permission of the publisher.

The change from the rural world of Barinas to Caracas was an abrupt one for Chávez. In the capital, he no longer had the kind of time he had once had for drinking all night with his friends. At the academy, he had to get up at the crack of dawn. There he searched for definitions that would eventually bring him closer than ever to the Ruiz family, and once he graduated he began to make contacts with recalcitrant members of the military and prominent figures of the Venezuelan left, the most radical of whom maintained clandestine ties with the governments of Libya, Iraq, North Korea, and Algeria.

His first two years in the academy, however, went by without much drama. "I worked hard there, but it never felt like a burden to me," he has said. Listening closely to his personal passions, Hugo Chávez combined his classes in military strategy and political theory with lessons in Venezuelan history, memorizing the long-winded proclamations of the South American Liberator Simón Bolívar that José Esteban Ruiz Guevara had taught him. Thanks to Ruiz Guevara, Chávez also fell under the spell of Ezequiel Zamora, a seminal figure in the history of the Venezuelan left whose motto was the unforgettable battle cry of "Popular elections, free land, and free men. Horror in the face of the oligarchy."

Chávez rapidly acquired a taste for life in the military. "By the time I dressed in blue for the first time, I already felt like a soldier," he once said. Once a goal, baseball was now a mere pastime. According to his own account, this was true from his very first year in the military academy, when he was given "a uniform, a gun, an area, close-order formation, marches, morning runs, studies in military science, and science in general … in short, I liked it. The courtyard. Bolívar in the background. … I was like a fish in water. It was as if I had discovered the essence or at least part of the essence of life, my true vocation." This same enthusiasm bubbled forth in one of the letters he wrote to his grandmother, in which he decribed the military life as a great adventure:

Grandma, if you had only seen me firing away like a maniac in our maneuvers. First we worked on instinctive shooting -- immediate action, daytime attack, infiltration, etc. Then we went on a march -- 120 kilometers -- and at the end we performed a simulation of war. The enemy was attacking us at dawn, and we would have ended up soaking wet if we couldn't pitch the mountain tents. We walked through little villages where the girls stared at us in awe and the little kids cried, they were so scared.

In 1971, after being promoted to full-fledged cadet, Chávez was given two days' leave. In his blue uniform and white gloves, he went alone to the old cemetary, the Cementario General al Sur, in Southern Caracas. "I had read that [star baseball pitcher Néstor Isaías] Látigo Chávez was buried there. And I went because I had a knot inside of me, a kind of debt that came out of that oath, that prayer. … I was letting go of it, and now I wanted to be a soldier. … I felt bad about it." Locating the spot where his old idol had been laid to rest, he prayed and asked him for forgiveness. "I started talking to the gravestone, with the spirit that penetrated everything there, talking to myself. It was as if I was saying to him. 'Isaías. I'm not going down that path anymore. I'm a soldier now.' And as I left the cemetery, I was free.'"

Why would Chávez, a young soldier, feel the need to explain his decisions to a dead idol? Beyond the possible psychoanalytic interpretations, events like this may suggest a way of viewing history as a series of hidden meanings, plans, and oaths that suggest the certainty that one has been tapped for a very great destiny.

Hugo Chávez continued playing baseball, and often, but as a diversion, not a vocation. He still painted occasionally, too, and would get up and sing every chance he got. A corrido llanero that begins "Furia se llamó el caballo" (Fury was the name of the horse) became a personal leitmotif of sorts. His fellow cadets, who considered him the best pitcher of the lot, baptized him "EI Zurdo Furia" -- the Left-handed Fury. Yet, despite all this, the decision had already been made. That, at least, is how Hugo Chávez, president, has processed his memories. "It wasn't just that I felt like a soldier; at the academy my political motivation flourished, as well. I couldn't pinpoint one specific moment, it was a process that began to replace everything that, until then, had been my dreams and my daily routine: baseball, painting, girls."