From the biography, Hugo Chávez, by Alberto Barrera and Christina Marcano (Random House, 2007). Reprinted with permission of the publisher.

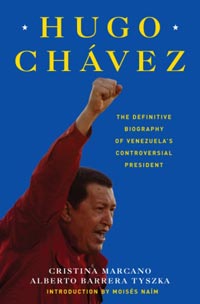

Despite the internal criticism that continues to flow, there was no doubt that by late 2006, Hugo Chávez was Latin America's most influential leader. A consummately newsworthy figure whose face graces the covers of countless magazines and the front pages of newspapers everywhere, it is hard to believe that ten years ago he was just a skinny former coup plotter, an unemployed nobody who received little or no attention from the Venezuelan media. The little boy who played baseball in Barinas is finally what he always wanted to be: an international celebrity.

When Fidel Castro became ill in mid-2006 and announced his temporary leave of absence from the presidency, many people began to make predictions about Hugo Chávez's potential role in Cuba. Many of his followers even went so far as to hypothesize that he was on his way to becoming the political successor of the Cuban revolutionary in Latin America.

A few weeks later, on August 13, 2006, the rumors of Castro's death suddenly came to a halt when the Venezuelan president made a trip to Havana. "This is the best trip of my life, better even than when I used to travel to see my first girlfriend," Chávez said jokingly after a conversation with Castro on the occasion of the Cuban leader's eightieth birthday, portions of which were broadcast on Cubavisión.

Chávez is clearly proud of his friendship with the most legendary Latin American politician of the twentieth century and tends to offer optimistic reports regarding his health. Observers note that Chávez's bond with Raúl Castro will never be as strong, but they also dismiss the idea that Fidel's death will have any impact on the close relations Venezuela and Cuba presently enjoy.

Controversial and magnetic in the media, Chávez has ensured that he will remain a fixture all across Latin America, far beyond the exposure that his friendship with Fidel Castro offers him. The Venezuelan president has a guaranteed stage wherever he goes, as well as sympathizers ready to applaud him and swoon from his charisma. A controversial supporter of efforts to aid the poor, whether they are Bolivarians from Potosí or gringos in the Bronx, Hugo Chávez is no longer a tropical curiosity, and hasn't been for a long time.

Chávez masterfully exploits the disenchantment of people who feel excluded for whatever reason, and he feeds on controversy whenever he can. A considerable amount of his fame stems from his anti-imperialist stance and his fierce antagonism for the man believed to be the most powerful in the world, George W. Bush, whom he has recently been calling "Mr. Danger."

Chávez loves to measure himself up against the American president and never misses a chance to call Bush a murderer responsible for acts of genocide. For Chávez, Bush is both a tool and an obsession. The comandante has accused his opposition of obediently following the librettos of the CIA and has even gone so far as to attribute natural disasters and climate change to the American president's refusal to sign the Kyoto protocols.

But not everything is rhetoric. In the middle of 2005, the government decided to raise the tax paid by multinational oil companies operating in Venezuela, from 1 percent to 16 percent at first and to 30 percent by 2006. Local analysts considered the measure to be fair, given that when the 1 percent rate was established, crude oil was at $12 a barrel, whereas by January 2006 it had reached $60. Given the vast income derived from the oil business, the companies in question did not object.

Chávez has questioned the policies of the Bush administration from the very heart of the empire. In September 2005, while in New York to attend the U.N. General Assembly, he joined Jesse Jackson and Democratic congressman José Serrano on a visit to the Bronx, where he told local residents that he would invest a portion of Venezuela's petrodollars in health and environmental programs.

The president walked through the Bronx neighborhood serenaded by the Latin rhythms provided by a local band. He gave hugs all around, evoking shades of Che Guevara with comments like "The present is a struggle, the future belongs to us" and stopping for a moment to dance and play the congas. He seemed magnanimous and very much in his element.

"We are going to save the world, not for us, we are fifty-one years old, but for you," the Venezuelan president said to a needy young woman who, he said, reminded him of his daughters.

Shortly afterward, the president established a humanitarian program to provide 25 million gallons of oil to heat the homes of the poorest residents of the northeastern United States, through the Venezuelan-owned CITGO. The program was designed to help out some 100,000 families and, according to certain analysts, humiliate Bush on his own turf. The idea came from a group of Democratic senators who sent letters to the principal oil distributors in the country, asking them to sell fuel oil at a discount to the neediest communities. CITGO was the only company that responded to the initiative.

The White House, often befuddled when dealing with the Chávez phenomenon, decided to take action in 2005, when Bush declared the Venezuelan president "a threat to regional stability," "decertified" Venezuela in the fight against the drug trade, and blocked the sale of Brazilian and Spanish planes -- the manufacture of which required U.S. parts -- to the Venezuelan armed forces.

Though the tension between the two countries frequently approaches the breaking point, both presidents have taken care to back away from an official rift. Two episodes from 2005 illustrate this well: at one point Chávez threatened to break off relations if the U.S. judicial authorities did not approve the extradition of the anti-Castro activist Luis Posada Carriles, but when the Venezuelan request was rejected, no further action was taken. And in the middle of the year, the Venezuelan president ordered the suspension of the country's agreement with the DEA claiming that certain agents had been involved in "intelligence infiltration that threatened the security and defense of the country." But by January 2006 the two countries had worked out a new bilateral agreement.

One month later, relations froze over when the Venezuelan government had John Correa, the naval attaché at the U.S. Embassy in Caracas, expelled from Venezuela under accusations of espionage. In response, the U.S. government ordered Jenny Figueredo, the general secretary of the Venezuelan Embassy in Washington, to leave the United States.

Chávez's most memorable anti-imperialist moment, however, came when he took the stage at the U.N. General Assembly in September 2006. "The Devil came here yesterday. It still smells like sulfur today," declared the Venezuelan president in reference to U.S. President George Bush, whom, later on in Harlem, Chávez described as an "alcoholic" with "a lot of hang-ups."

His thundering words caused a fair amount of disgruntlement in the United States, but they did not affect business in any real way. According to an estimate that the U.S. Embassy in Caracas released a month after the incident, the Venezuela-U.S. trade balance for 2006 may well have topped $50 billion, which would be a 25 percent increase over the previous year and the highest dollar amount in recent years. The lion's share of their deals these days revolve around Venezuela's export of oil and oil-derivative products to the U.S. market. In 2005, bilateral trade between the two countries reached $40 billion, with Venezuelan exports accounting for $32 billion and U.S. exports for only $8 billion of this colossal pie.

In the Venezuelan daily El Nacional, U.S. Ambassador William Brownfield underscored the importance of accepting the fact that Venezuela and the United States were bound to have ideological and philosophical differences. He also observed that these differences would not go away and instead focused on the fact that there are plenty of other things both nations agree upon -- such as economics.

The effect of the Bush-Chávez dynamic can be felt all across Latin America. The Venezuelan leader has had serious run-ins with government leaders he considers to be allies of Washington (Mexico's Vicente Fox, Peru's Alejandro Toledo, Colombia's Alvaro Uribe) and has cultivated alliances with the leftist governments that have emerged up and down the continent. Though he may have been something of an inconvenience to certain leaders in the beginning, Chávez has conquered more and more territory, and nowadays there are few who can resist the generous offers of his "petrodiplomacy."