Last February, Continental Flight 3407 crashed outside of Buffalo, N.Y., killing 49 people onboard and one on the ground. Although 3407 was painted in the colors of Continental Connection, it was actually operated by Colgan Air, a regional airline that flies routes under contract for US Airways, United and Continental. The crash and subsequent investigation revealed a little-known trend in the airline industry: Major airlines have outsourced more and more of their flights to obscure regional carriers.

Today, with regional airlines accounting for more than half of all scheduled domestic flights in the United States and responsible for the last six fatal commercial airline accidents, FRONTLINE producer Rick Young and correspondent Miles O'Brien investigate the safety issues associated with outsourcing in Flying Cheap.

"No doubt in our mind that when she's buying this ticket, she's buying a flight on Continental," says Scott Maurer, who lost his daughter, Lorin, on 3407. "She believed she had Continental pilots and Continental safety and Continental service, but, you know, we know different today."

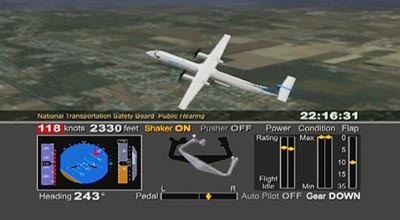

An investigation of the crash by the National Transportation Safety Board was recently completed and identified pilot error as a major factor in the accident. But the investigation has also put the spotlight on operations of regional airlines like Colgan Air, where the first officer on 3407 had made less than $16,000 the previous year and the captain had failed five flight tests and received inadequate training on a critical safety system involved in the crash.

[Read here Colgan Air's reaction to this FRONTLINE report.]

Clay Foushee, a congressional investigator and former airline executive, calls the crash a watershed event. "It's become the symbol of everything that's wrong with the industry." Bill Voss, president of the Flight Safety Foundation, seconds that: "There are some accidents that really make you step back and take a look at what's happening in the system. [Flight] 3407 forces us to look at issues like commuting, fatigue. It forces us to look at training. It forces us to look at fundamental regulatory relationships. It's a very important event."

The industry turned to regional outsourcing in the wake of deregulation and competitive pressure from new low-cost carriers such as Southwest. Former Continental CEO Gordon Bethune was a leader in the new formula. Outsourcing helped Continental remain more competitive and avoid another bankruptcy as they bid more routes out. "Having an independent allows an airline to bid that and have a competitive relationship and make sure they get their flying done at the lowest cost," explains Bethune. John Prater, president of the Air Line Pilots Association, says: "The major airlines created the regional industry as a way of lowering costs. They wanted to find a way of getting rid of experience. They wanted to find a way of getting rid of that expensive employee, and let's start this new industry and call it the regional industry."

The regional industry argues that flying is safer than ever. Despite the string of accidents among the regionals, the overall fatality rate has continued to decline since deregulation. "The regulations and shared responsibility that have been built over decades have given American travelers the safest system of transportation the world has ever known," says Roger Cohen, president of the Regional Airline Association.

FRONTLINE talked with many regional pilots, including several former Colgan pilots, who speak publicly for the first time. They tell about the pressures to meet contractual responsibilities and avoid delays or canceled flights in spite of sickness, fatigue or broken plane parts. It is a practice in the industry known as pilot pushing. "They said safety was a priority a lot," says one former Colgan pilot. "In my experience, however, on a day-to-day basis, being on time and completing the flight was much more important, much more important." Says another former Colgan pilot: "The saying around the company was always, 'Move the rig.' And that just kind of told me that they were willing to kind of push the bounds in order to make money."

The pressure pilots face is rooted in the intense competition among regionals to win major airlines' flying contracts. FRONTLINE reveals details of the contracts, known as code-share agreements, which raise safety concerns among industry experts. "They get paid based on a completion factor in some contracts, which raises a disturbing question," says Foushee, Northwest's former vice president of flight operations. "Are we incentifying [sic] regional carriers to actually complete segments when it may not be safe to do so, when the safest thing may be to cancel that flight or divert to a different airport?"

The FRONTLINE investigation also examines how well the Federal Aviation Administration, the agency responsible for overseeing safety of the airline industry, has been doing its job. Documents and interviews obtained by FRONTLINE indicate the agency was aware of significant and repeated safety concerns at Colgan Air dating back more than a decade.

Flying Cheap is a FRONTLINE co-production with the American University School of Communication’s Investigative Reporting Workshop.